86–88 High Street, Slough, Berkshire, SL1 1EL

The author George Orwell described his ideal pub in a newspaper article and called it ‘Moon Under Water’. It is why ‘moon’ is used in the name of several Wetherspoon pubs. This pub stands on the site of the Black Boy Inn. First recorded in 1679, it was demolished in 1910 and replaced by the Fulbrook Motor Works. Later known as Fulbrook House, it was home to Slough’s first supermarket and then the Halifax Building Society.

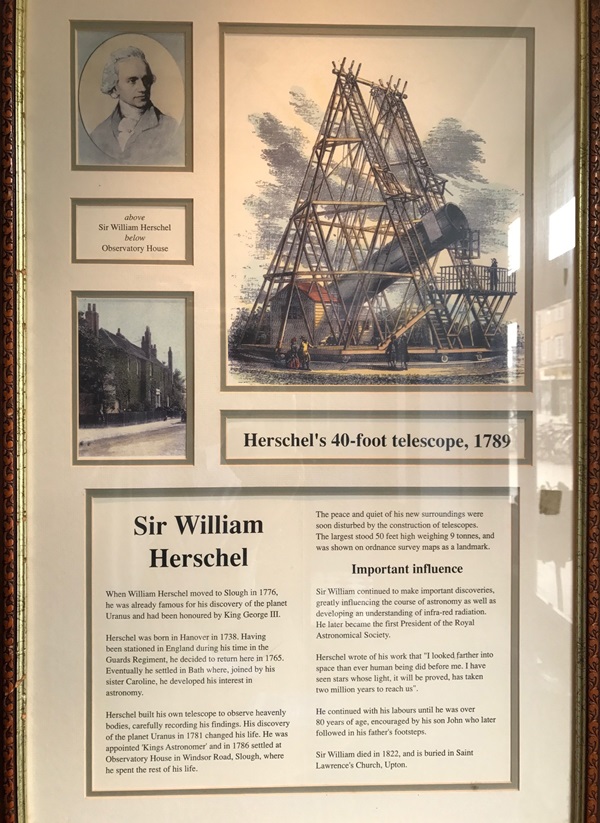

Prints and text about Sir William Herschel.

The text reads: When William Herschel moved to Slough in 1776, he was already famous for his discovery of the planet Uranus and had been honoured by King George III.

Herschel was born in Hanover in 1738. Having been stationed in England during his time in the Guards Regiment, he decided to return here in 1765. Eventually he settled in Bath where, joined by his sister Caroline, he developed his interest in astronomy.

Herschel built his own telescope to observe heavenly bodies, carefully recording his findings. His discovery of the planet Uranus in 1781 changed his life. He was appointed King Astronomer and in 1786 settled at Observatory House in Windsor Road, Slough, where he spent the rest of his life.

The peace and quiet of his new surroundings were soon disturbed by the construction of telescopes. The largest stood 50 feet high weighing 9 tonnes, and was shown on ordnance survey maps as a landmark.

Sir William continued to make important discoveries, greatly influencing the course of astronomy as well as developing an understanding of infra-red radiation. He later became the first President of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Herschel wrote of his work that “I looked farther into space than ever human being did before me. I have seen stars whose light, it will be proved, has taken two million years to reach us”.

He continued with his labours until he was over 80 years of age, encouraged by his son John who later followed in his father’s footsteps.

Sir William died in 1822, and is buried in Saint Lawrence’s Church, Upton.

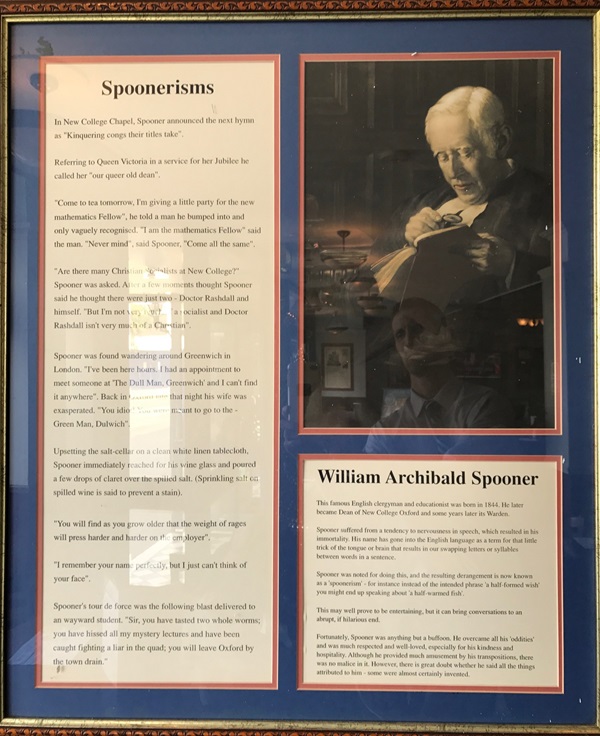

A print and text about spoonerisms and William Archibald Spooner.

The text reads: Spoonerisms

In New College Chapel, Spooner announced the next hymn as “Kinquering congs their titles take”.

Referring to Queen Victoria in a service for her Jubilee he called her “our queer old dean”.

“Come to tea tomorrow, I’m giving a little party for the new mathematics Fellow”, he told a man he bumped into and only vaguely recognised. “I am the mathematics Fellow” said the man. “Never mind”, said Spooner, “Come all the same”.

“Are there many Christian Socialists at New College?” Spooner was asked. After a few moments Spooner said he thought there were just two – Doctor Rashdall and himself. “But I’m not very much a socialist and Doctor Rashdall isn’t very much of a Christian”.

Spooner was found wandering around Greenwich in London. “I’ve been here hours. I had an appointment to meet someone at The Dull Man, Greenwich and I can’t find it anywhere”. Back in Oxford late that night his wife was exasperated. “You idiot! You were meant to go to the Green Man, Dulwich”.

Upsetting the salt-cellar on a clean white linen tablecloth, Spooner immediately reached for his wine glass and poured a few drops of claret over the spilled salt. (Sprinkling salt on spilled wine is said to prevent a stain.)

“You will find as you grow older that the weight of rages will press harder and harder on the employer”.

“I remember your name perfectly, but I just can’t think of your face.”

Spooner’s tour de force was the following blast delivered to a wayward student. “Sir, you have tasted two whole worms; you have hissed all my mystery lectures and have been caught fighting a liar in the quad; you will leave Oxford by the town drain”.

William Archibald Spooner

The famous English clergyman and educationist was born in 1844. He later became Dean of New College Oxford and some years later its Warden. Spooner suffered from a tendency to nervousness in speech, which resulted in his immortality. His name has gone into the English language as a term for that little trick of the tongue or brain the results in our swapping letters of syllables between words in a sentence. Spooner was noted for doing this, and the resulting derangement is now known as a spoonerism – for instance instead of the intended phrase ‘a half-formed wish’ you might end up speaking about ‘a half-warmed fish’. This may well prove to be entertaining, but it can bring conversations to an abrupt, if hilarious end.

Fortunately, Spooner was anything but a buffoon. He overcame all his oddities and was much respected and well-loved, especially for his kindness and hospitality. Although he provided much amusement by his transpositions, there was no malice in it. However, there is great doubt whether he said all the things attributed to him – some were almost certainly invented.

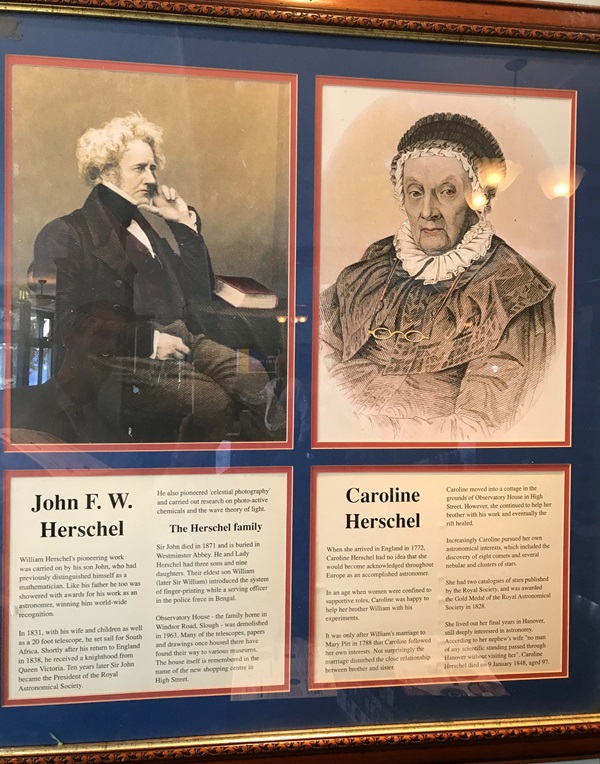

Prints and text about John Herschel and Caroline Herschel.

The text reads: John FW Herschel

William Herschel’s pioneering work was carried on by his son John, who had previously distinguished himself as a mathematician. Like his father he too was showered with awards for his work as an astronomer, winning him world-wide recognition. In 1831, with his wife and children as well as a 20 foot telescope, he set sail for South Africa. Shortly after his return to England in 1838, he received a knighthood from Queen Victoria. Ten years later Sir John became the President of the Royal Astronomical Society. He also pioneered celestial photography and carried out research on photo-active chemicals and the wave theory of light.

Sir John died in 1871 and is buried in Westminster Abbey. He and Lady Herschel had three sons and nine daughters. Their eldest son William (later Sir William) introduced the system of finger-printing while a serving officer in the police force in Bengal.

Observatory House – the family home in Windsor Road, Slough – was demolished in 1963. Many of the telescopes, papers and drawings once housed there have found their way to various museums. The house itself is remembered in the name of the new shopping centre in High Street.

Caroline Herschel

When she arrived in England in 1772, Caroline Herschel had no idea that she would become acknowledged throughout Europe as an accomplished astronomer. In an age when women were confined to supportive roles, Caroline was happy to help her brother William with his experiments. It was only after William’s marriage to Mary Pitt in 1788 that Caroline followed her own interests. Not surprisingly the marriage disturbed the close relationship between brother and sister. Caroline moved into a cottage in the grounds of the Observatory House in High Street. However, she continued to help her brother with his work and eventually the rift healed. Increasingly Caroline pursued her own astronomical interests, which included the discovery of eight comets and several nebulae and clusters of stars.

She had two catalogues of stars published by the Royal Society, and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828. She lived out her final years in Hanover, still deeply interested in astronomy. According to her nephew’s wife “no man of a scientific standing passed through Hanover without visiting her”. Caroline Herschel died on 9 January, 1848 aged 97.

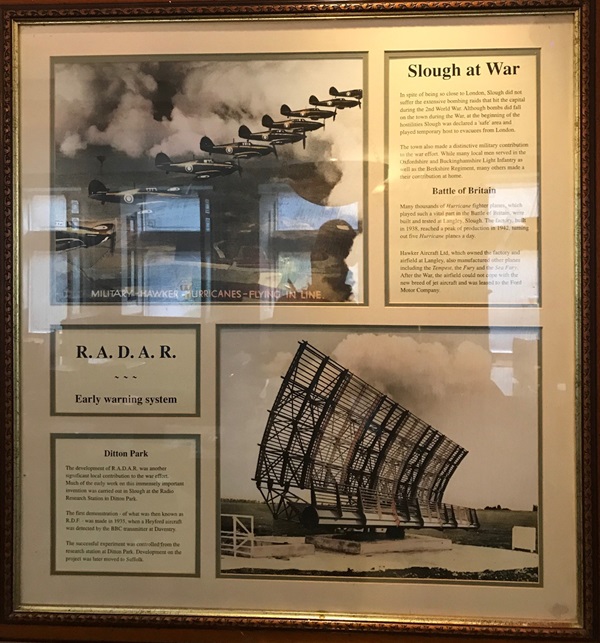

Prints and text about Slough at war and R.A.D.A.R.

The text reads: Slough at War

In spite of being so close to London, Slough did not suffer the extensive bombing raids that hit the capital during the 2nd World War. Although bombs did fall on the town during the war, at the beginning of the hostilities Slough was declared a safe area and played temporary host to evacuees from London.

The town also made a distinctive military contribution to the war effort. While many local men served in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry as well as the Berkshire Regiment, many others made their contribution at home.

Many thousands of Hurricane fighter planes, which played such a vital part in the Battle of Britain, were built and tested in Langley, Slough. The factory, built in 1938, reached a peak of production in 1942, turning out five Hurricane planes a day.

Hawker Aircraft Ltd, which owned the factory and airfield at Langley, also manufactured other planes including the Tempest, the Fury and the Sea Fury. After the war, the airfield could not cope with the new breed of jet aircraft and was leased to the Ford Motor Company.

R.A.D.A.R

The development of R.A.D.A.R was another significant local contribution to the war effort. Much of the early work on this immensely important invention was carried out in Slough at the Radio Research Station in Ditton Park.

The first demonstration – of what was then known as R.D.F. – was made in 1935, when a Heyford aircraft was detected by the BBC transmitter at Daventry.

The successful experiment was controlled from the research station at Ditton Park. Development on the project was later moved to Suffolk

Prints and text about the history of transport in Slough.

The text reads: The Coaching Age

Although horse drawn coaches had been in use for some time, the great days of coaching date from the latter part of the 17th century.

It was the development of coaching that gave Slough a new importance and several coaching inns sprang up, growing in number during the 18th century.

Coach travel was a distinct improvement on travelling by cart or wagon, but it was still an uncomfortable and lengthy affair.

In 1667 advertisements boasted that the Flying Machine could make the journey from London to Bath (via Slough) in just three days!

Fifty years later the first daily service on this route was started by Thomas Baldwin – the landlord of the Crown Inn, Slough.

The journey could take as little as 38 hours, but the poor state of the roads, often little more than mud tracks, frequently delayed coaches by several days.

Acts of Parliament like the Colnbrook Turnpike Trust in 1727 eventually led to better roads, and improved coach design brought greater comfort. However, coach travel was dealt a fatal blow with the arrival of the railways in the 1840s.

The Old Henley – the last of the Bath Road coaches – was taken off the road, after 45 years’ service, on 8 October 1850.

The first mail coach was introduced in 1774, travelling from Bath to London passing through Slough.

Eventually the Post Office gave permission for the mail coach to stop at Colnbrook, to drop all the letters destined for Slough. The mail was then carried into the town at the cost of one (old) penny.

This lasted until 1841, when a post office was opened in the town. In 1893 a purpose built post office was built on the corner of High Street and Chandos Street. It was demolished in 1973 after a replacement had opened in the Queensmere Shopping Centre.

The arrival of the railway

The first proposal to build a railway through Slough was as early as 1824. However, five years later the nearest thing to a locomotive to be seen in the town was Sir Goldsworthy Gurney’s steam omnibus.

In 1832 the Great Western Railway Company was formed. A few months later the company appointed Isambard Kingdom Brunel as its engineer to build a line from Bath to London, via Slough.

The prospect of railway created considerable excitement. While many saw the advantages of this new form of transport, there was also vigorous opposition to the proposal.

When the railway bill was defeated in Parliament in July 1834, a celebration dinner was held in the Windmill Hotel in Slough.

It proved to be a short lived victory for those who opposed the building of a railway. Within twelve months the bill received royal assent and became law.

It was not long before the Premier, the Vulcan and the North Star made trial trips along the route. In May 1838 The Thunderer made several trips from Slough to Paddington, just a few days before the line was officially opened.

After visiting the works at Maidenhead the directors of the G.W.R. returned to Salt Hill, where some 300 people were provided with a cold luncheon and refreshments. The party then travelled on to Paddington, taking 34 minutes to complete the 19 mile journey.

At least one of the directors seems to have fully enjoyed the luncheon. An article in The Times – on 2 June 1838 – reports how he walked along the tops of the carriages while the train was at full speed.

A number of very distinguished passengers were among the first to use the new railway in Slough. In November 1839 Prince Albert, accompanied by his brother Prince Ernest, made his first journey by rail, travelling from Slough to Paddington.

Queen Adelaide was the first to use the royal saloon on a visit to Slough in July 1840. In January 1842 the same royal carriage was used by King Frederick William IV of Prussia, who travelled from Slough to London to see the sights of the capital.

Queen Victoria overcame her initial reluctance and boarded the royal train for the first time in June 1842, travelling from Slough to London with Prince Albert.

Above: The first mail coach, 1784

Below: Isambard Kingdom Brunel

A modern artist’s impression of an earlier work called Slough High Street, by the Berkshire artist William Redworth.

The text reads: The Moon and Spoon site has a previous history as a licensed premises. According to Richard Bentley in his publication Some Historic Inns of Slough there was once an ancient tavern called The Black Boy Inn on this site, a fact mentioned in the Upton Court Rolls of 1679. It is described as a small two-storey brick and timber building with somewhat meagre accommodation. The entrance to the pub from the side walk was a step down due to continuous improvements to the busy coaching roach to Bath. Whether the inn acquired its name from Sir Robert Viner’s celebrated The Black Boy Inn at Swakeleys near Uxbridge, we may never know. However, Samuel Pepys in his diary (September 7, 1665) describes seeing the mummy of a boy, who, after death, had been dried in an oven, and was then carefully preserved in a special case which had been made for it. There is also a tradition that the Highwayman, Claude Duval frequented The Black Boy in Slough. This is quite likely as he rented a house in Wokingham. Duval carried out some of his most famous exploits on Hounslow Health and Maidenhead Thicket. Sadly the Black Boy Inn was demolished in 1910 and its bricks and mortar were carted away to The Mere which was Richard Bentley’s house at Upton, for use in making garden paths. Today The Moon and Spoon trades on the same site as the old Black Boy Inn, but is now a modern forward looking pub offering the same value for money as it did back in 1995 when it first opened.

A statue made of spoons, in reference to the pub’s name.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk