The site of this pub was once occupied by the Hope Brewery which had its own pub, The Hope Tap. According to the earliest trade directory, 103–104 Friar Street were occupied by the brewery, but by 1860 the brewery had gone.

A print and text about brewing in Reading.

The text reads: By the mid 18th century, Reading’s once staple industry of cloth-making had spun into decline, and the town needed to change to meet new industrial demands. Meanwhile, great London breweries of the day, such as Truman, Whitbread and Barclay Perkins, were doubling their output to 800,000 barrels a year. However, none carried out their own malting and depended on supplies from other countries.

Reading’s waterway system played a vital role in the town’s entry into the world of brewing. Reading established itself as a significant malt supply area. Huge barges headed downstream to the capital carrying some of the largest quantities of malt (up to 120 tons) in the country.

Such success brought wealth to Reading’s maltsters, who set up local breweries. By 1790, there were four in Reading and more by the mid 19th century. Among them was the Hope Brewery, which owned The Hope Tap. Demolished in the 19th century, it stood on the site of this pub, which bears its name.

By far the most successful brewery was begun by William Simonds, in Broad Street, in 1785. He soon moved his fast growing business to Bridge Street. Mary Willis, widow of another wealthy maltster Binfield Willis, who died in 1782, re-married Joseph Huntley, and used some of her money to set up the Huntley biscuit shop in London Street.

Above: Simonds Brewery steam lorry, c1924.

Photographs and text about Oscar Wilde.

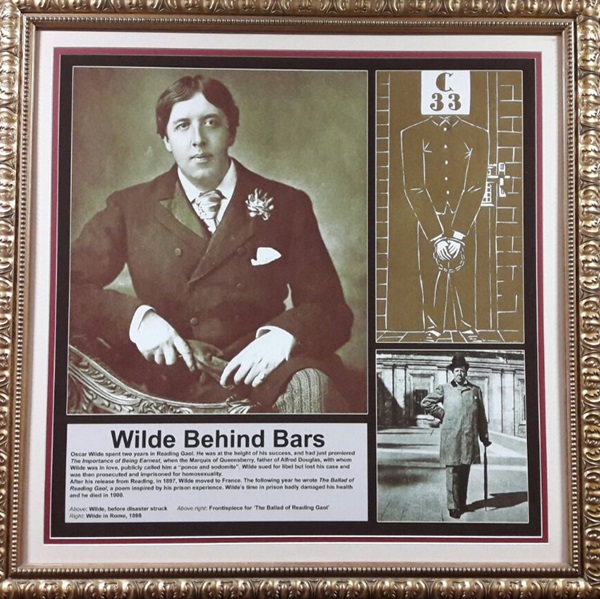

The text reads: Oscar Wilde spent two years in Reading Gaol. He was at the height of his success, and had just premiered The Importance of Being Earnest, when the Marquis of Queensberry, father of Alfred Doulas, with whom Wilde was in love, publicly called him a “ponce and sodomite”. Wilde sued for libel but lost his case and was then prosecuted and imprisoned for homosexuality.

After his release from Reading, in 1897, Wilde moved to France. The following year he wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a poem inspired by his prison experience. Wilde’s time in prison badly damaged his health and he died in 1900.

Above: Wilde, before disaster struck

Above right: Frontispiece for The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Right: Wilde in Rome, 1898.

Illustrations and text about the Greyfriars of Friar Street.

The text reads: Friar Street takes its name from a group of Franciscan monks who first came to Reading in 1234. They brought with them a letter from Pope Gregory IX, requiring the Abbot of Reading to give them a plot of land to build a friary.

Unhappy at the presence of this rival monastic order, established by Saint Francis of Assissi, the Abbot gave them the swampiest land he could find, on the south bank of the Thames, near Caversham Bridge. The Greyfriars struggled to make a living, but often found themselves cut off from Reading by mud and water.

In 1285 they appealed for help to the Archbishop of Canterbury, a fellow Franciscan, and within three years they were given the site where Greyfriars Church now stands in Friar Street.

It was completed in 1311, and what remains represents the most complete Franciscan building in Britain.

During the dissolution of the monasteries, around 1540, Thomas Cromwell ordered the church’s closure. Most of the land, buildings and valuables were sold. Internal decorations and stained glass windows were defaced. What remained was then looted.

The church became the town’s guildhall and thirty years later, around 1570, was used as a hospital and workhouse. It’s most depressing transformation was yet to come!

Above: left, Thomas Cromwell and his master, King Henry VIII, right, Thomas Cromwell, the Hammer of the Monks.

Prints and text about William Havell.

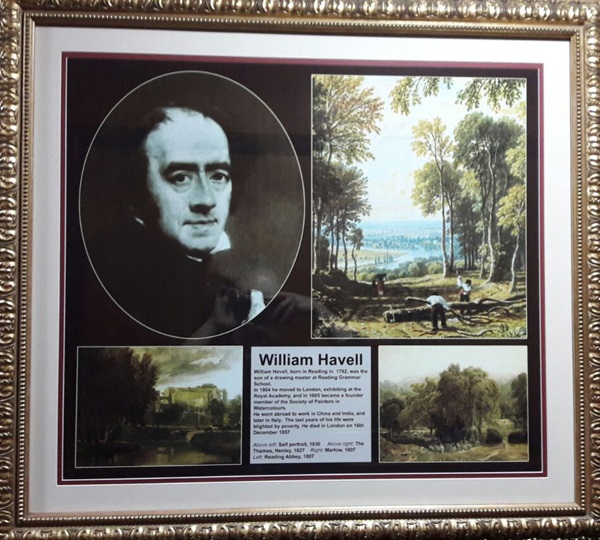

The text reads: William Havell, born in Reading in 1782, was the son of a drawing master at Reading Grammar School.

In 1804 he moved to London, exhibiting at the Royal Academy, and in 1805 became a founder member of the Society of Painters in Watercolours.

He went abroad to work in China and India, and later in Italy. The last years of his life were blighted by poverty. He died in London on 16 December 1857.

Above left: Self-portrait, 1830

Above right: The Thames, Henley, 1827

Right: Marlow, 1807

Left: Reading Abbey, 1807.

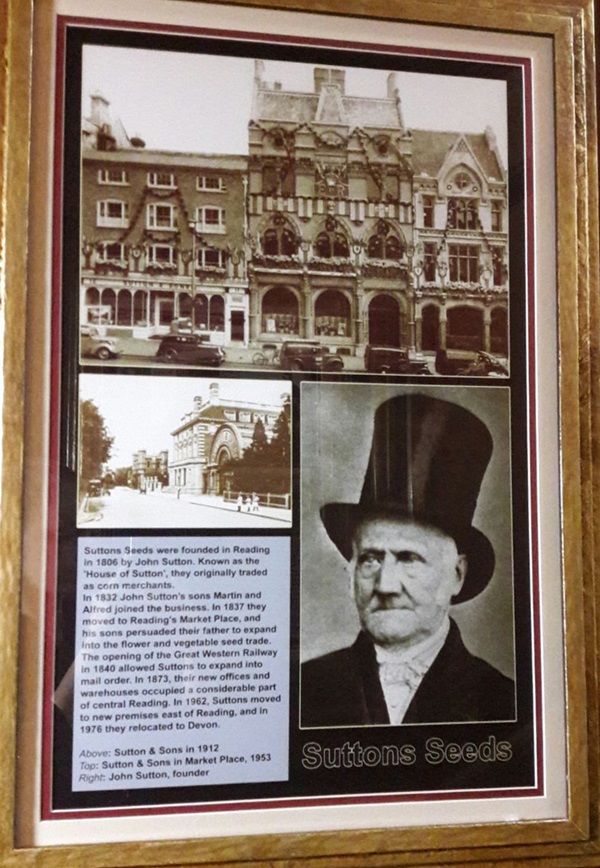

Photographs and text about Suttons Seeds.

The text reads: Suttons Seeds were founded in Reading in 1806 by John Sutton. Known as the House of Sutton, they originally traded as corn merchants.

In 1832 John Sutton’s sons Martin and Alfred joined the business. In 1837 they moved to Reading’s Market Place, and his sons persuaded their father to expand into the flower and vegetable seed trade.

The opening of the Great Western Railway in 1840 allowed Suttons to expand into mail order. In 1873, their new offices and warehouses occupied a considerable part of central Reading. In 1962, Suttons moved to new premises east of Reading, and in 1976 they relocated to Devon.

Above: Sutton and Sons in 1912

Top: Sutton and Sons in Market Place, 1953

Right: John Sutton, founder.

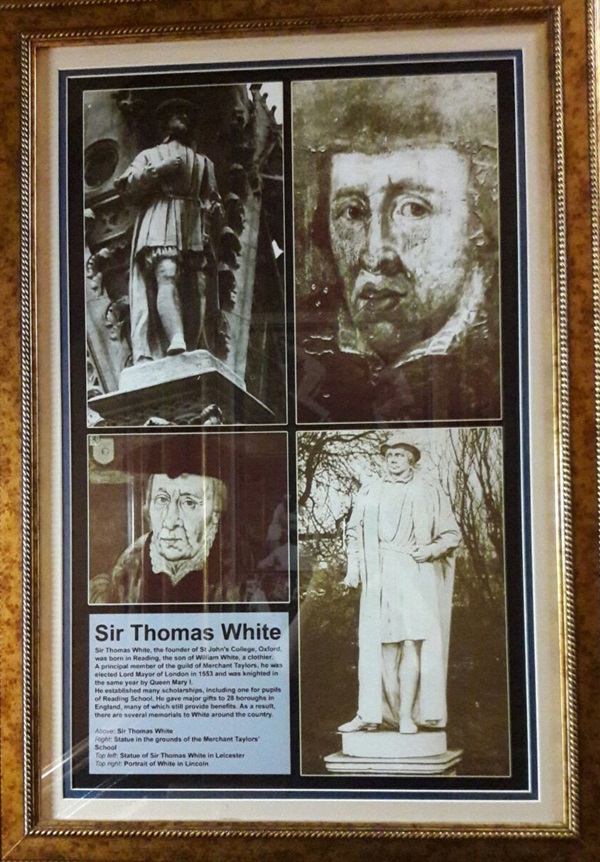

Illustrations, photographs and text about Sir Thomas White.

The text reads: Sir Thomas White, the founder of St John’s College, Oxford, was born in Reading, the son of William White, a clothier. A principal member of the guild of Merchant Taylors, he was elected lord mayor of London in 1553 and was knighted in the same year by Queen Mary I.

He established many scholarships, including one for pupils of Reading School. He gave major gifts to 28 boroughs in England, many of which still provide benefits. As a result, there are several memorials to White around the country.

Above: Sir Thomas White

Right: Statue in the grounds of the Merchant Taylors’ School

Top left: Statue of Sir Thomas White in Leicester

Top right: Portrait of White in Lincoln.

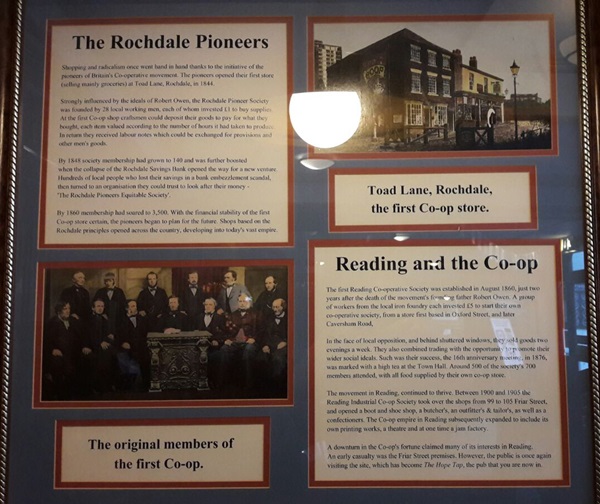

Prints and text about the Co-op in Reading.

The text reads: The Rochdale Pioneers

Shopping and radicalism once went hand in hand thanks to the initiative of the pioneers of Britain’s Co-operative movement. The pioneers opened their first store (selling mainly groceries) at Toad Lane, Rochdale, in 1844.

Strongly influenced by the ideals of Robert Owen, the Rochdale Pioneer Society was founded by 28 local working men, each of whom invested £1 to buy supplies. At the first Co-op shop, craftsmen could deposit their goods to pay for what they bought, each item valued according to the number of hours it had taken to produce. In return they received labour notes which could be exchanged for provisions and other men’s goods.

By 1848 society membership had grown to 140 and was further boosted when the collapse of the Rochdale Savings Bank opened the way for a new venture. Hundreds of local people who lost their savings in a bank embezzlement scandal, then turned to an organisation they could trust to look after their money – The Rochdale Pioneers Equitable Society.

By 1860 membership had soared to 3,500. With the financial stability of the first Co-op store certain, the pioneers began to plan for the future. Shops based on the Rochdale principles opened across the country, developing into today’s vast empire.

Reading and the Co-op

The first Reading Co-operative Society was established in August 1860, just two years after the death of the movement’s founding father Robert Owen. A group of workers from the local iron foundry each invested £5 to start their own Co-operative society, from a store first based in Oxford Street, and later Caversham Road.

In the face of local opposition, and behind shuttered windows, they sold goods two evenings a week. They also combined trading with the opportunity to promote their wider social ideals. Such was their success, the 16th anniversary meeting, in 1876, was marked with a high tea at the Town Hall. Around 500 of the society’s 700 members attended, with all food supplied by their own Co-op store.

The movement in Reading, continued to thrive. Between 1900 and 1905 the Reading Industrial Co-op Society took over the shops from 99 to 105 Friar Street, and opened a boot and shoe shop, a butcher’s, an outfitter’s and tailors, as well as a confectioners. The Co-op empire in Reading subsequently expanded to include its own printing works, a theatre and at one time a jam factory.

A downturn in the Co-op’s fortune claimed many of its interests in Reading. An early casualty was the Friar Street premises. However, the public is once again visiting the site, which has become The Hope Tap, the pub that you are now in.

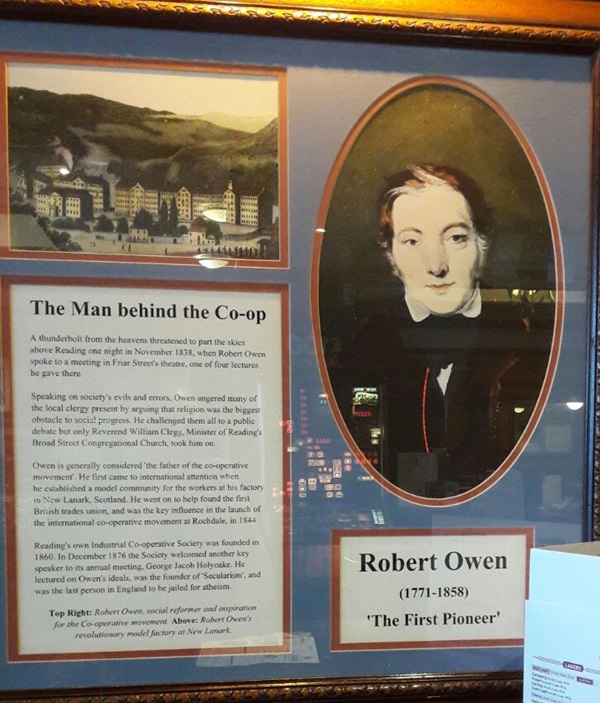

Prints and text about Robert Owen.

The text reads: A thunderbolt from the heavens threatened to part the skies above Reading one night in November 1838, when Robert Owen spoke to a meeting in Friar Street’s theatre, one of four lectures he gave there.

Speaking on society’s evils and errors, Owen angered many of the local clergy present by arguing that religion was the biggest obstacle to social progress. He challenged them all to a public debate but only Reverend William Clegg, minister of Reading’s Broad Street Congregational Church, took him on.

Owen is generally considered ‘the father of the Co-operative movement’. He first came to international attention when he established a model community for the workers at his factory in New Lanark, Scotland. He went on to help found the first British trade union, and was the key influence in the launch of the international Co-operative movement at Rochdale, in 1844.

Reading’s own Industrial Co-operative Society welcomed another key speaker to its annual meeting. George Jacob Holyoake. He lectured on Owen’s ideals, was the founder of Secularism, and was the last person in England to be jailed for atheism.

Top Right: Robert Owen, social reformer and inspiration for the Co-operative movement

Above: Robert Owen’s revolutionary model factory at New Lanark.

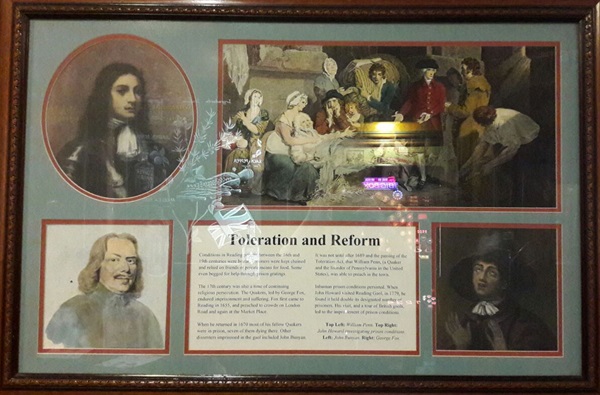

Prints and text about toleration and reform.

The text reads: Conditions in Reading prisons between the 16th and 19th centuries were brutal. Prisoners were kept chained and relied on friends or private means for food. Some even begged for help through prison gratings.

The 17th century was also a time of continuing religious persecution. The Quakers, led by George Fox, endured imprisonment and suffering. Fox first came to Reading in 1655 and preached to crowds on London Road and again at the Market Place.

When he returned in 1670 most of his fellow Quakers were in prison, seven of them dying there. Other dissenters imprisoned in the gaol included John Bunyan.

It was not until after 1689 and the passing of the Toleration Act, that William Penn, (a Quaker and the founder of Pennsylvania in the United States), was able to preach in the town.

Inhuman prison conditions persisted. When John Howard visited Reading Gaol, in 1779, he found it held double its designated number of prisoners. His visit, and a tour of British gaols, led to the improvement of prison conditions.

Top Left: William Penn

Top Right: John Howard investigating prison conditions

Left: John Bunyan

Right: George Fox.

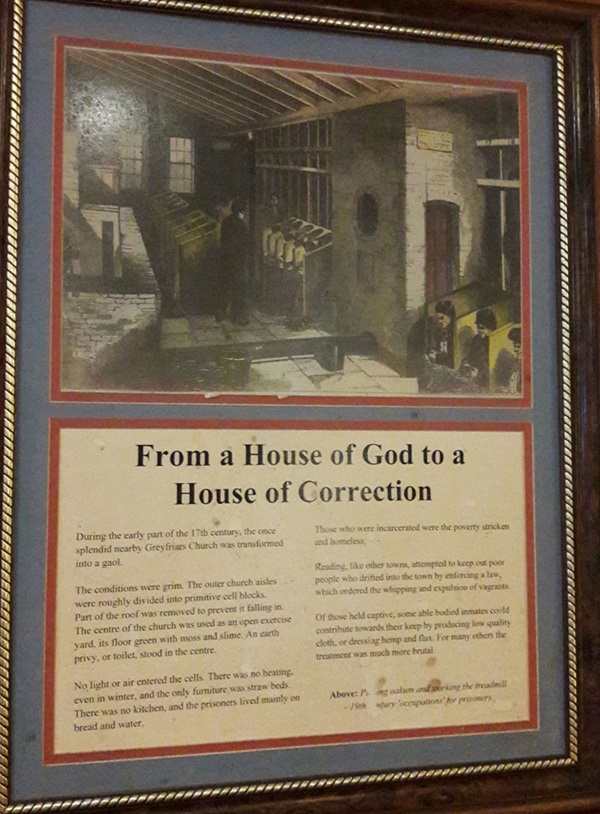

A print and text about Greyfriars Church.

The text reads: During the early part of the 17th century, the once splendid nearby Greyfriars Church was transformed into a gaol.

The conditions were grim. The outer church aisles were roughly divided into primitive cell blocks. Part of the roof was removed to prevent it falling in. The centre of the church was used as an open exercise yard, its floor green with moss and slime. An earth privy, or toilet, stood in the centre.

No light or air entered the cells. There was no heating, even in winter, and the only furniture was straw beds. There was no kitchen, and the prisoners lived mainly on bread and water.

Those who were incarcerated were the poverty stricken and homeless.

Reading, like other towns, attempted to keep out poor people who drifted into the town by enforcing a law, which ordered the shipping and expulsion of vagrants.

Of those held captive, some able bodied inmates could contribute towards their keep by producing low quality cloth, or dressing hemp and flax. For many others the treatment was much more brutal.

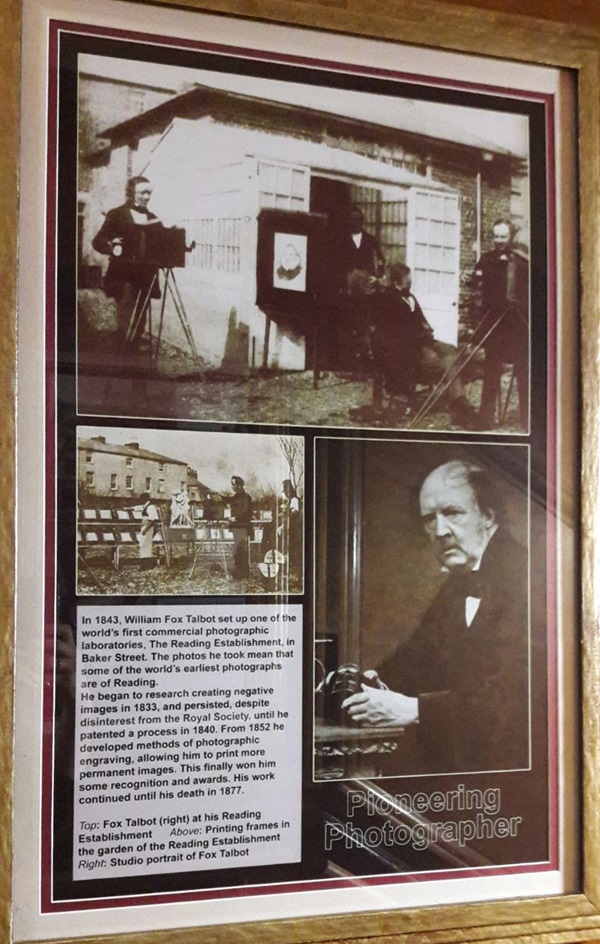

Photographs and text about William Fox Talbot.

The text reads: In 1843, William Fox Talbot set up one of the world’s first commercial photographic laboratories, The Reading Establishment, in Baker Street. The photos he took mean that some of the world’s earliest photographs are of Reading.

He began to research creating negative images in 1833, and persisted, despite disinterest from the Royal Society, until he patented a process in 1840. From 1852 he developed methods of photographic engraving, allowing him to print more permanent images. This finally won him some recognition and awards. His work continued until his death in 1877.

Top: Fox Talbot (right) at his Reading Establishment

Above: Printing frames in the garden of the Reading Establishment

Right: Studio portrait of Fox Talbot.

The Oracle, founded by John Kendrick, photographed by Fox Talbot in 1850.

Prints of Friar Street, Town Hall and St Laurence’s Church.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk