The ‘leaning tower of Bristol’ is a curious landmark. The off-vertical tower of Temple Church is all that remains of the church built in the 1390s (and blitzed in World War II) which had replaced the original church on the site built by the Knights Templar. This one-time order of warrior monks had been granted land here known as ‘Temple Fee’ by Robert, Earl of Gloucester (son of Henry I). It included Temple Meads (or meadows), now the site of Bristol’s main railway station and the adjacent Quay Point development, where this pub is located in Temple Square.

A print and text about the Great Western Railway, at Temple Meads Station.

The text reads: This J.D. Wetherspoon pub in Temple Square is just behind Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s original Temple Meads Station. Built in 1839-41, to look like a Tudor mansion, it is the world’s oldest surviving railway terminus.

The terminus, engine sheds, and office buildings were constructed for the Great Western Railway Company.

Brunel was the Company’s Chief Engineer, in charge of creating a rail link between Bristol and London. Brunel was born in 1896, the son of Marc Isambard Brunel, himself a civil engineer, and a refugee from the French Revolution.

The two men worked together on the tunnel under the Thames. Nicknamed “God’s Wonderful Railway”, the GWR was built as a broad-gauge line, with rails seven feet apart, and more than two feet wider than standard.

Although the system gave a smoother ride, it was difficult to integrate with the other companies standard-gauge lines and was phased out by 1892.

The first GWR train from Bristol to Bath hauled by the locomotive Fire-Ball, ran in 1840. However, it was another year before the line reached London, after the completion of the two mile long Box Tunnel.

Prints of Temple Meads Station, 1846.

Prints of an historical Bristol.

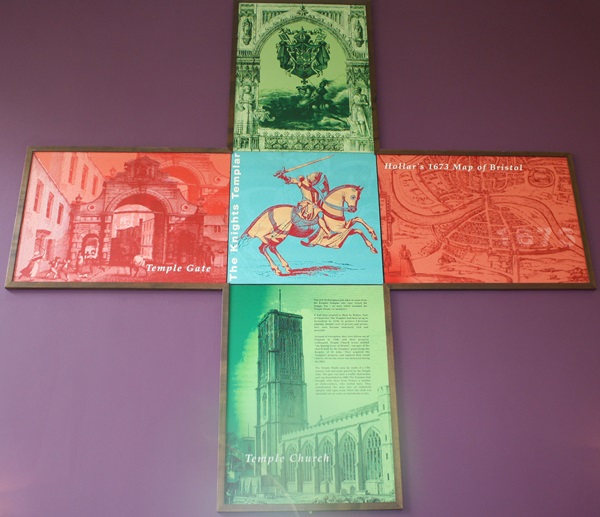

A print and text about the Temple Fee.

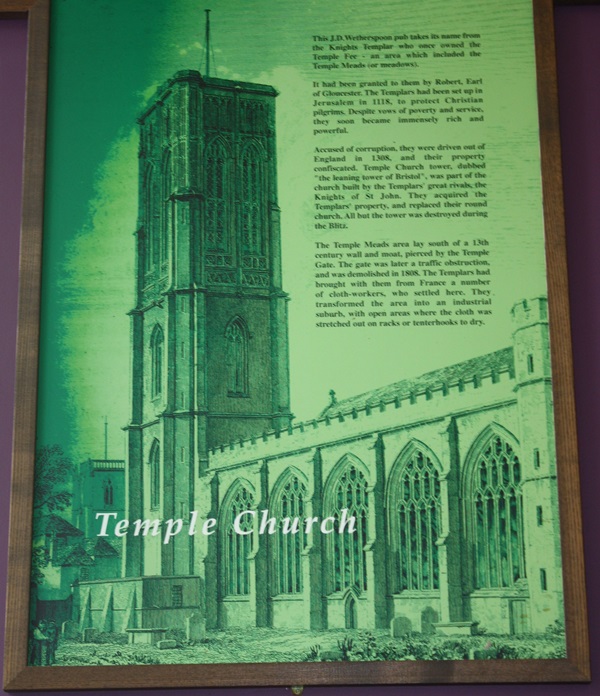

The text reads: This J.D. Wetherspoon pub takes its name from the Knights Templar who once owned the Temple Fee – an area which included the Temple Meads (or meadows).

It had been granted to them by Robert, Earl of Gloucester. The Templars had been set up in Jerusalem in 1118, to protect Christian pilgrims. Despite vows of poverty and service, they soon became immensely rich and powerful.

Accused of corruption, they were driven out of England in 1308, and their property confiscated. Temple Church tower, dubbed “the leaning tower of Bristol”, was part of the church built by the Templars’ great rivals, the Knights of St John. They acquired the Templars’ property, and replaced their round church. All but the tower was destroyed during the Blitz.

The Temple Meads area lay south of a 13th century wall and moat, pierced by the Temple Gate. The gate was later a traffic obstruction, and was demolished in 1808. The Templars had brought with them from France a number of cloth-workers, who settled here. They transformed the area into an industrial suburb, with open areas where the cloth was stretched out on racks or tenterhooks to dry.

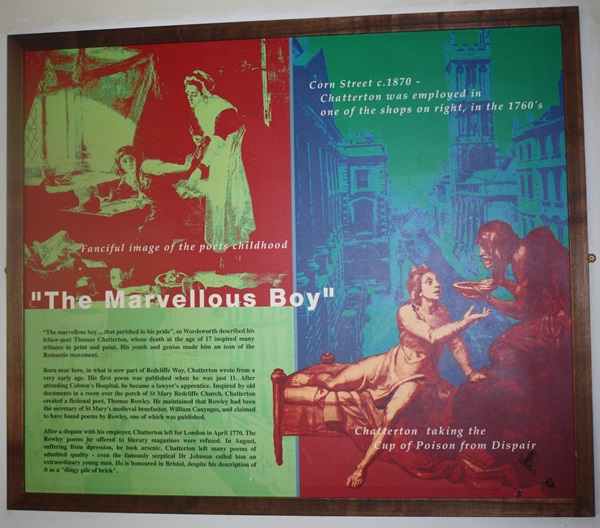

Prints and text about Thomas Chatterton.

The text reads: “The marvellous boy … that perished in his pride”, so Wordsworth described his fellow-poet Thomas Chatterton, whose death at the age of 17 inspired many tributes in print and paint. His youth and genius made him an icon of the Romantic movement.

Born near here, in what is now part of Redcliffe Way, Chatterton wrote from a very early age. His first poem was published when he was just 11. After attending Colston’s Hospital, he became a lawyer’s apprentice. Inspired by old documents in a room over the porch of St Mary’s Redcliffe Church, Chatterton created a fictional poet, Thomas Rowley. He maintained that Rowley had been the secretary of St Mary’s medieval benefactor, William Canynges, and claimed to have found poems by Rowley, one of which was published.

After a dispute with his employer, Chatterton left for London in April 1770. The Rowley poems he offered to literary magazines were refused. In August, suffering from depression, he took arsenic. Chatterton left many poems of admitted quality – even the famously sceptical Dr Johnson called him an extraordinary young man. He is honoured in Bristol, despite his description of it as a “dingy pile of brick”.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk