The building next to the old chapel has the words ‘Post Office’ in the panel over its main doors. However, the former post office was originally a substantial private residence. Built in c1850, this grade II listed building was called Sandford House, where Charles Sandford Windover set up home with his family. Windover was the mayor of Huntingdon in 1886.

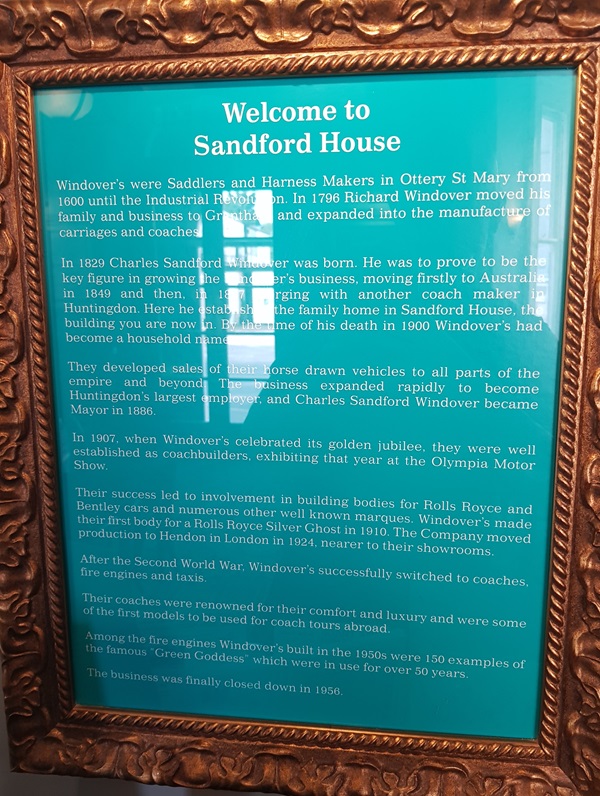

Text about Sandford House.

The text reads: Windover’s were Saddlers and Harness Makers in Ottery St Mary from 1600 until the Industrial Revolution. In 1796 Richard Windover moved his family and business to Grantham and expanded into the manufacture of carriages and coaches.

In 1829 Charles Sandford Windover was born. He was to prove to be the key figure in growing the Windover’s business, moving firstly to Australia in 1849 and then, in 1847, merging with another coach maker in Huntingdon. Here he established the family home in Sandford House, the building you are now in. By the time of his death in 1900 Windover’s had become a household name.

They developed sales of their horse drawn vehicles to all parts of the empire and beyond. The business expanded rapidly to become Huntingdon’s largest employer, and Charles Sandford Windover became Mayor in 1886.

In 1907, when Windover’s celebrated its golden jubilee, they were well established as coachbuilders, exhibiting that year at the Olympia Motor Show.

Their success led to involvement in building bodies for Rolls Royce and Bentley cars and numerous other well-known marques. Windover’s made their first body for a Rolls Royce Silver Ghost in 1910. The Company moved production to Hendon in London in 1924, nearer to their showrooms.

After the Second World War, Windover’s successfully switched to coaches, fire engines and taxis.

Their coaches were renowned for their comfort and luxury and were some of the first models to be used for coach tours abroad.

Among the fire engines Windover’s built in the 1950s were 150 examples of the famous “Green Goddess” which were in use for over 50 years.

The business was finally closed down in 1956.

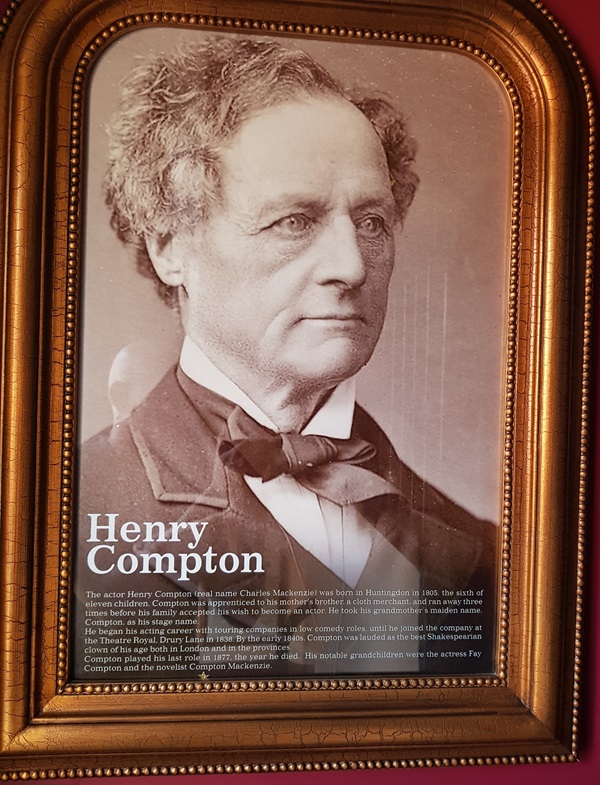

A photograph and text about Henry Compton.

The text reads: The actor Henry Compton (real name Charles Mackenzie) was born in Huntingdon in 1805, the sixth of eleven children. Compton was apprenticed to his mother’s brother, a cloth merchant, and ran away three times before his family accepted his wish to become an actor. He took his grandmother’s maiden name, Compton, as his stage name.

He began his acting career with touring companies in low comedy roles, until he joined the company at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1838. By the early 1840s, Compton was lauded as the best Shakespearian clown of his age both in London and in the provinces.

Compton played his last role in 1877, the year he died. His notable grandchildren were the actress Fay Compton and the novelist Compton Mackenzie.

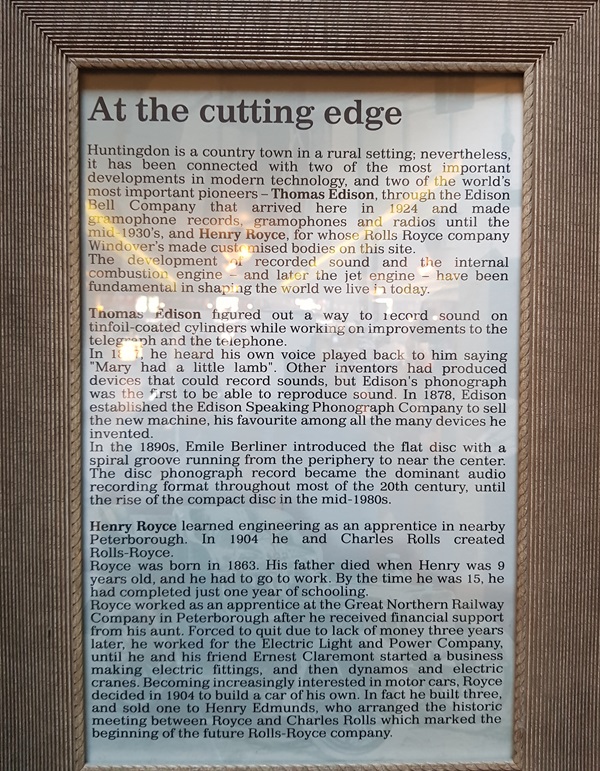

Text about Thomas Edison and Henry Royce.

The text reads: Huntingdon is a country town in a rural setting; nevertheless, it has been connected with two of the most important developments in modern technology, and two of the world’s most important pioneers – Thomas Edison, through the Edison Bell Company that arrived here in 1924 and made gramophone records, gramophones and radios until the mid 1930s, and Henry Royce, for whose Rolls Royce company Windover’s made customised bodies on this site.

The development of recorded sound and the internal combustion engine – and later the jet engine – have been fundamental in shaping the world we live in today.

Thomas Edison figured out a way to record sound on tinfoil-coated cylinders while working on improvements to the telegraph and the telephone.

In 1837, he heard his own voice played back to him saying “Mary had a little lamb”. Other inventors had produced devices that could record sounds, but Edison’s phonograph was the first to be able to reproduce sound. In 1878, Edison established the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to sell the new machine, his favourite among all the many devices he invented.

In the 1890s, Emile Berliner introduced the flat disc with a spiral groove running from the periphery to near the centre. The disc phonograph record became the dominant audio recording format throughout most of the 20th century, until the rise of the compact disc in the mid-1980s.

Henry Royce learned engineering as an apprentice in nearby Peterborough. In 1904 he and Charles Rolls created Rolls-Royce.

Royce was born in 1863. His father died when Henry was 9 years old, and he had to go to work. By the time he was 15, he had completed just one year of schooling.

Royce worked as an apprentice at the Great Northern Railway Company in Peterborough after he received financial support from his aunt. Forced to quit due to lack of money three years later, he worked for the Electric Light and Power Company, until he and his friends Ernest Claremont started a business cranes. Becoming increasingly interested in motor cars, Royce decided in 1904 to build a car of his own. In fact he built three, and sold one to Henry Edmunds, who arranged the historic meeting between Royce and Charles Rolls which marked the beginning of the future Rolls-Royce company.

A photograph of Charles Sandford Windover.

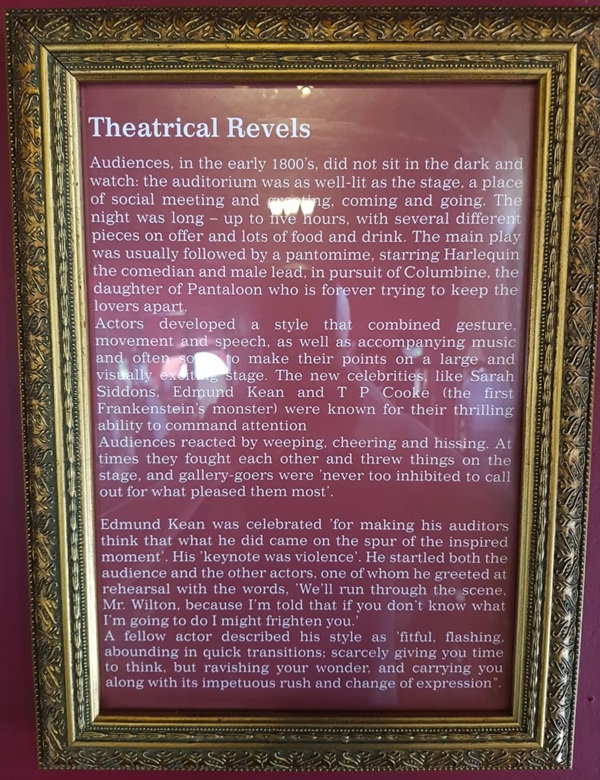

Text about the theatre in Huntingdon.

The text reads: Audiences, in the early 1800s, did not sit in the dark and watch: the auditorium was as well-lit as the stage, a place of social meeting and greeting, coming and going. The night was long – up to five hours, with several different pieces on offer and lots of food and drink. The main play was usually followed by a pantomime, starring Harlequin the comedian and male lead, in pursuit of Columbine, the daughter of Pantaloon who is forever trying to keep the lovers apart.

Actors developed a style that combined gesture, movement and speech, as well as accompanying music and often so to make their points on a large and visually exciting stage. The new celebrities, like Sarah Siddons, Edmund Kean and T P Cooke (the first Frankenstein’s monster) were known for their thrilling ability to command attention.

Audiences reacted by weeping, cheering and hissing. At times they fought each other and threw things on the stage, and gallery-goers were ‘never too inhibited to call out for what pleased them most’.

Edmund Kean was celebrated ‘for making his auditors think that what he did came on the spur of the inspired moment’. His ‘keynote was violence’. He startled both the audience and the other actors, one of whom he greeted at rehearsal with the words, ‘We’ll run through the scene, Mr Wilton, because I’m told that if you don’t know what I’m going to do I might frighten you.’

A fellow actor described his style as “fitful, flashing, abounding in quick transitions; scarcely giving you time to think, but ravishing your wonder, and carrying you along with its impetuous rush and change of expression”.

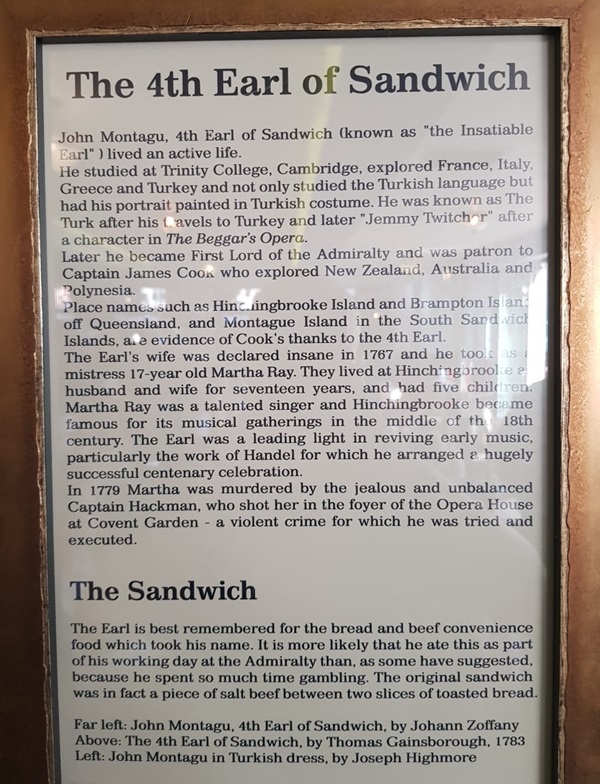

Text about the 4th Earl of Sandwich.

The text reads: John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich (known as “the Insatiable Earl”) lived an active life.

He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, explored France, Italy, Greece and Turkey and not only studied the Turkish language but had his portrait painted in Turkish costume. He was known as The Turk after his travels to Turkey and later Jemmy Twitcher after a character in The Beggar’s Opera.

Later he became First Lord of the Admiralty and was patron to Captain James Cook who explored New Zealand, Australia and Polynesia.

Place names such as Hinchingbrooke Island and Brampton Island off Queensland, and Montague Island in the South Sandwich Islands, are evidence of Cook’s thanks to the 4th Earl.

The Earl’s wife was declared insane in 1767 and he took as a mistress 17-year old Martha Ray. They lived at Hinchingbrooke as husband and wife for seventeen years, and had five children. Martha Ray was a talented singer and Hinchingbrooke became famous for its musical gatherings in the middle of the 18th century. The Earl was a leading light in reviving early music, particularly the work of Handel for which he arranged a hugely successful centenary celebration.

In 1779 Martha was murdered by the jealous and unbalanced Captain Hackman, who shot her in the foyer of the Opera House at Covent Garden – a violent crime for which he was tried and executed.

The Earl is best remembered for the bread and beef convenience food which took his name. It is more likely that he ate this as part of his working day at the Admiralty than, as some have suggested, because he spent so much time gambling. The original sandwich was in fact a piece of salt between two slices of toasted bread.

A print and text about Hinchingbrooke House.

The text reads: Hinchingbrooke House was built around an 11th century nunnery. After the Reformation it passed into the hands of the Cromwell family, and subsequently became the home of the Earls of Sandwich.

In 1538, Richard Williams (alias Cromwell), whilst working for Thomas Cromwell overseeing the dissolution of the monasteries, was granted ‘the nunnery of Hinchingbrooke’ for the undervalued price of £19, 9s, 2d. His son, Henry Williams (alias Cromwell) – a grandfather of Oliver Cromwell – built the house adjoining to the nunnery.

Sir Oliver Cromwell, son of Sir Henry Cromwell and the last of the family to reside at the property, was uncle to Oliver Cromwell whose anti-Royalist campaigns during the English Civil War ended with the execution of the King Charles I and his personal elevation to ‘Lord Protector’ until his death in 1658.

It was Sir Oliver Cromwell who made the greatest impact on Hinchingbrooke House, making extensive alterations and additions to the growing country mansion, and providing hospitality to King James I on several occasions. Eventually this lavish entertainment drained him financially, and in 1627 he was forced to sell the estate.

Hinchingbrooke was purchased by Edward Montagu, the 1st Earl of Sandwich. The house remained with this family, until 1962.

In 1970, it became part of Hinchingbrooke School, housing the 6th form. Hinchingbrooke School was formerly Huntingdon Grammar School which, on the site of what is now the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon, was attended by Oliver Cromwell and Samuel Pepys. The school now has around 1900 pupils.

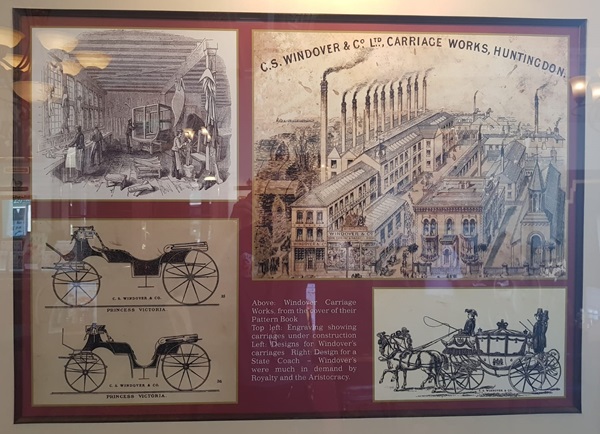

Illustrations and photographs of Windover’s works.

Above: Windover Carriage Works, from the cover of their Pattern Book

Top left: Engraving showing carriages under construction

Left: Designs for Windover’s carriages

Right: Design for a State Coach – Windover’s were much in demand by Royalty and the Aristocracy.

Above: Mr H Coote’s Delauney Belleville Car: coachwork by Windover’s 1909

Left: A 1925 Windover Rolls Royce at Moti Mahal Palace, with the Duke of Edinburgh on board

Top right: Windover’s car body work production

Right: Sandford House and the Windover Works, c1910.

North East view of Hinchingbrooke House by Buck, 1730.

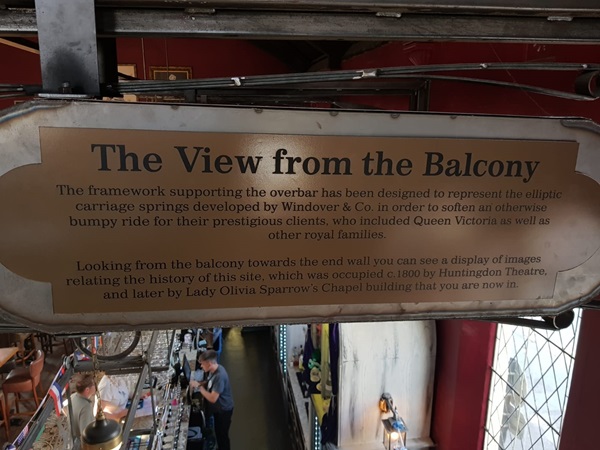

The framework supporting the overbar has been designed to represent the elliptic carriage springs developed by Windover & Co. in order to soften an otherwise bumpy ride for their prestigious clients, who included Queen Victoria as well as other royal families.

Looking from the balcony towards the end wall you can see a display of images relating the history of this site, which was occupied c.1800 by Huntingdon Theatre, and later by Lady Olivia Sparrow’s Chapel building that you are now in.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk