18–22 Church Terrace, Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, PE13 1BL

This pub comprises a former furniture and decorating store and the old Royal public house. Before 1869, The Royal was called The Wheatsheaf, recorded at this address since 1792.

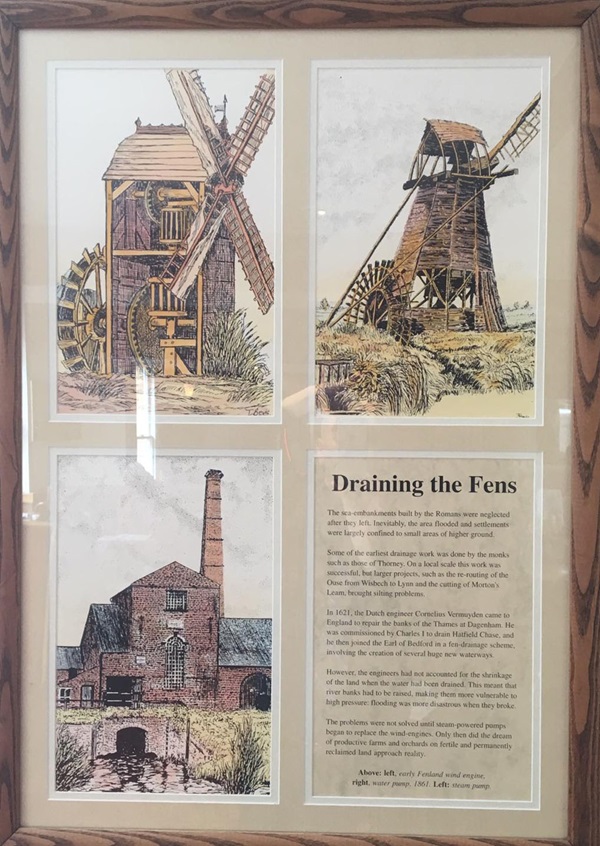

Illustrations and text about draining the fens.

The text reads: The sea-embankments built by the romans were neglected after they left. Inevitably, the area flooded and settlements were largely confined to small areas of higher ground.

Some of the earliest drainage work was done by the monks such as those of Thorney. On a local scale this work was successful, but larger projects, such as the re-routing of the Ouse from Wisbech to Lynn and the cutting of Morton’s Leam, brought sitting problems.

In 1621, the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vernuyden came to England to repair the banks of the Thames at Dagenham. He was commissioned by Charles I to drain Hatfield Chase, and he then joined the Earl of Bedford in a fen-drainage scheme, involving the creation of several huge new waterways.

However, the engineers had not accounted for shrinkage of the land when the water had been drained. This meant that river banks had to be raised, making them more vulnerable to high pressure: flooding was more disastrous when they broke

The problems were not solved until steam- powered pumps began to replace the wind- engines. Only then did the dream of productive farms and orchards on fertile and permanently reclaimed land approach reality.

Above: left, early Fenland wind engine, right, water pump, 1861

Left: Steam pump.

Text about Thomas Clarkson.

The text reads: The ornate memorial by the Town Bridge is dedicated to the anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Clarkson. He was born in 1760 at the Old Grammar School, where his father was headmaster. There is also a plaque in York Row, where he lived in a house once owned by Cromwell’s Secretary of State, John Thurloe.

The memorial, designed in 1881 by Sir George Gilbert Scott, also portrays two of Clarkson’s fellow abolitionists, William Wilberforce and Granville Sharp. Wilberforce Is the best-known of them, as he was chosen in 1787 as spokesman by the ‘committee for the abolition of the slave trade’.

However, it was Clarkson who was the driving force behind the campaign. His essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species was a best-seller in 1786. Clarkson organised boycotts and petitions, and produced many pamphlets detailing the inhumanity of the slave-trade.

Despite the huge profits derived from slavery, twenty years of tireless publicity and effort by Clarkson and his allies created a huge groundswell of public feeling that parliament was unable to ignore.

In 1807, a bill against slave- trading became law. But it made no provision for existing slaves in the British colonies, who were only freed in 1833. Elsewhere. However, slavery continued.

Prints and text about Wisbech and Fenland Museum.

The text reads: Wisbech has one of the oldest purpose-built museums in England, built in 1847. Its exhibits had been housed for the previous twelve years in a building in the Old Market. Unfortunately, the new building was constructed over the castle moat, and subsidence caused its brickwork to sag.

The museum’s greatest benefactor, who bequeathed it several thousand items in 1868, was the Rev Chauncey Hare Townshend. He was the owner of several local estates, and his local agent was secretary to the museum committee.

Townshend was a prolific collector. His London house contained over 4000 books, and 1400 paintings and prints, as well as collections of fossils, coins, porcelain and glass, clocks, photographs, jewellery, gemstones, maps, stuffed animals, and classical antiques. Two large wagons were needed to bring his bequest to Wisbech.

Townshend became a life-long friend of Charles Dickens, who dedicated Great Expectation to him, and gave him the manuscript now in the museum. The two had met via a shared interest in ‘mesmerism’, a form of hypnotism then much in fashion, believed to cure nervous disorders.

The museum is an exhibit in itself, having managed to retain much of its original Victorian design and fittings.

Right: top, Chauncey Hare Townshend, below, Townshend Road, 1920.

A painting of Wisbech by Eleanor Cherry.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk