The treasure trove of finds unearthed at the Foregate Street site included a rare blue bowl, made of glass, measuring eight inches across at the rim. Two square bottles, with reeded handles, and several flasks were also discovered. A large and well-used bronze key was probably the most notable of the smaller finds.

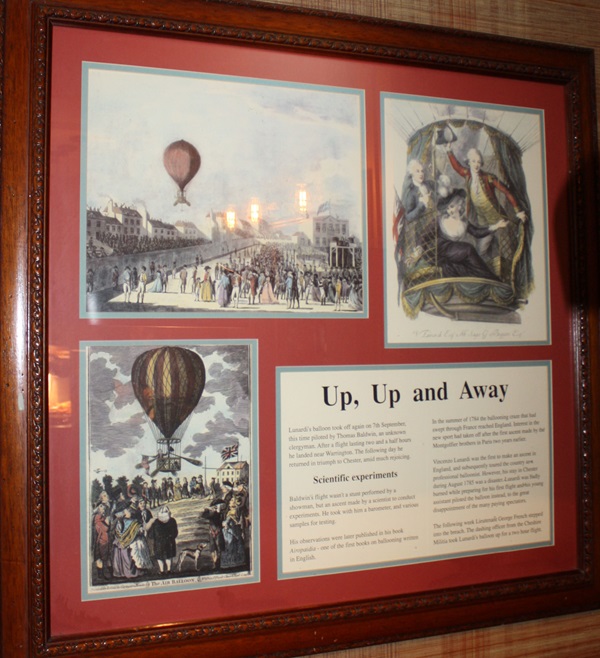

Prints and text about Vincenzo Lunardi and ballooning.

The text reads: Lunardi’s balloon took off again on 7th September, this time piloted by Thomas Baldwin, an unknown clergyman. After a flight lasting two and a half hours he landed near Warrington. The following day he returned in triumph to Chester, amid much rejoicing.

Baldwin’s flight wasn’t a stunt performed by a showman, but an ascent made by a scientist to conduct experiments. He took with him a barometer and various samples for testing.

His observations were later published in his book Airopaidia – one of the first books on ballooning written in English.

In the summer of 1784 the ballooning craze that had swept through France reached England. Interest in the new sport had taken off after the first ascent made by the Montgolfier brothers in Paris two years earlier.

Vincenzo Lunardi was the first to make an ascent in England, and subsequently toured the country as a professional balloonist. However, his stay in Chester during August 1785 was a disaster. Lunardi was badly burned while preparing for his first flight and his young assistant piloted the balloon instead, to the great disappointment of the many paying spectators.

The following week Lieutenant George French stepped into the breach. The dashing officer from the Cheshire Militia took Lunardi’s balloon up for a two hour flight.

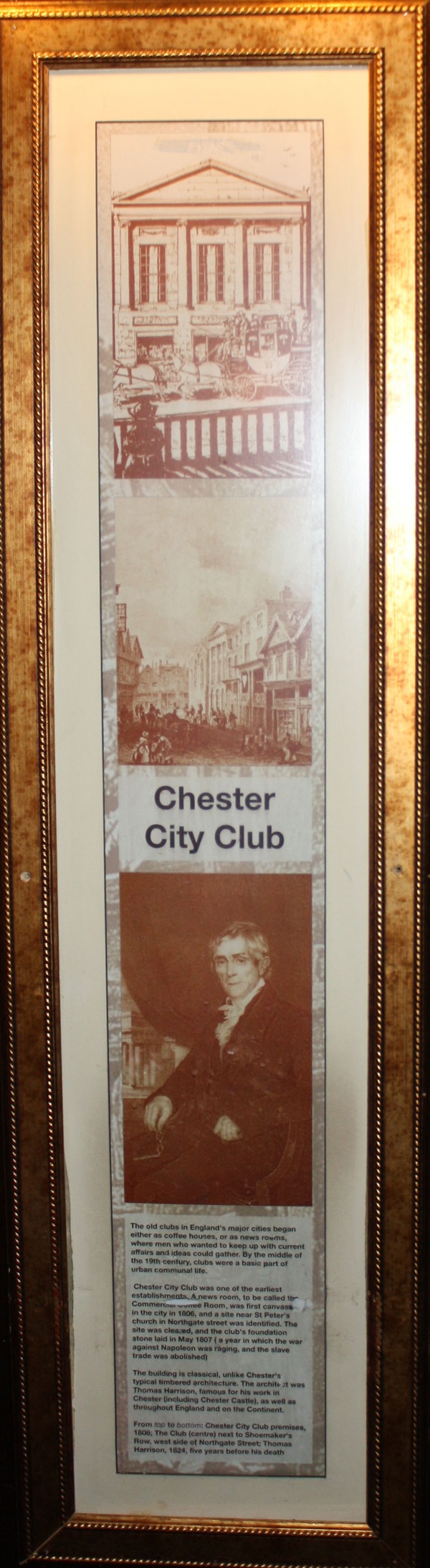

Illustrations and text about Chester City Club.

The text reads: The old clubs in England’s major cities began either as coffee houses, or as news rooms where men who wanted to keep up with current affairs and ideas who could gather. By the middle of the 19th century, clubs were a basic part of urban communal life.

Chester City Club was one of the earliest establishments. A news room, to be called the Commercial Coffee Room, was first canvassed in the city in 1806, and a site near St Peter’s church in Northgate street was identified. The site was cleared, and the club’s foundation stone laid in May 1807 (a year in which the war against Napoleon was raging, and the slave trade was abolished).

The building is classical, unlike Chester’s typical timbered architecture. The architect was Thomas Harrison, famous for his work in Chester (including Chester Castle), as well as throughout England and on the Continent.

From top to bottom: Chester City Club premises, 1808; The Club (centre) next to Shoemaker’s Row, west side of Northgate Street; Thomas Harrison, 1824, five years before his death.

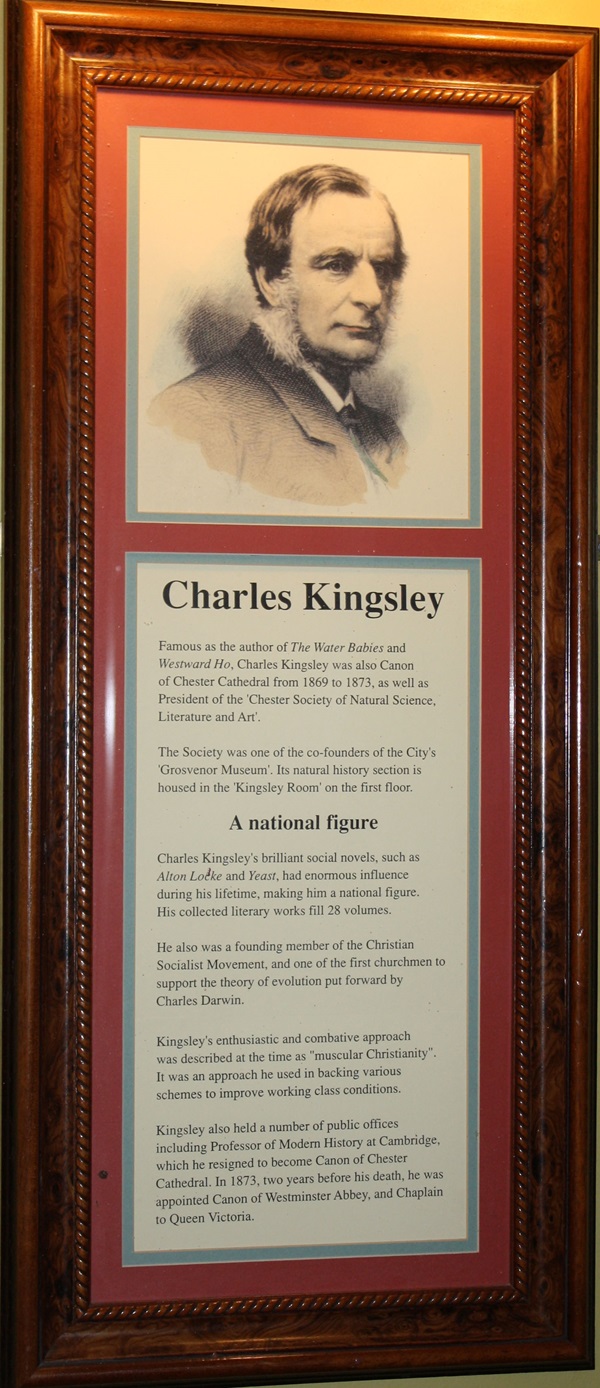

An illustration and text about Charles Kingsley.

The text reads: Famous as the author of The Water Babies and Westward Ho, Charles Kingsley was also Canon of Chester Cathedral from 1869 to 1873, as well as President of the Chester Society of Natural Science, Literature and Art.

The Society was one of the co-founders of the City’s Grosvenor Museum. Its natural history section is housed in the ‘Kingsley Rooms’ on the first floor.

Charles Kingsley’s brilliant social novels, such as Alton Locke and Yeast, had enormous influence during his lifetime, making him a national figure. His collected literary works fill 28 volumes.

He was also a founding member of the Christian Socialist Movement, and one of the first churchmen to support the theory of evolution put forward by Charles Darwin.

Kingsley’s enthusiastic and combative approach was described at the time as ‘muscular Christianity’. It was an approach he used in backing various schemes to improve working class conditions.

Kingsley also held a number of public offices including Professor of Modern History at Cambridge, which he resigned to become Canon of Chester Cathedral. In 1873, two years before his death, he was appointed Canon of Westminster Abbey, and Chaplain to Queen Victoria.

Prints, an illustration and text about the Theatre Royal.

The text reads: The Royal began its life as the New Theatre in the Old Wool Hall housed in St Nicholas’ Chapel in Northgate Street. Having received objection to performing unlicensed plays, the New Theatre applied successfully to the Crown for a licence.

Renamed as the Theatre Royal, it became one of the England’s earliest licensed provincial theatres. It was also Chester’s leading inn. The resident company was held in high regard and considered to be “as good as any Company of County Comedians in the country”.

The Royal also attracted some very famous actors. George Cooke appeared here in the role of ‘Hamlet’ in 1784. Cooke was one of the leading actors of his day, in spite of his heavy drinking.

Mrs Sarah Siddons, the undisputed queen on the stage, appeared in Otway’s Venice Preserved in 1786.

Three years later Mrs Jordan acted in two productions at the Royal. The following year she began her most famous role as mistress of the Duck or Clarence, later King William IV. During the liaison, which lasted more than 20 years, Dorothy Jordan bore the Duke ten children.

Edmund Kean played his celebrated Shakespearian role, Richard III, here in 1816. Kean became one of the most famous actors of his day, but, unable to cope, he turned to a life of drinking and debauchery.

By this time theatre-going had declined in popularity and few leading actors made the trip to the Royal. Increasingly the performance were geared to popular entertainment, like the ‘Fire King’ from Poland who was billed as dancing barefoot on hot iron and also holding his head in a charcoal fire.

Right: Mrs Jordan

Above left, Edmund Kean

Right, Mrs Siddons.

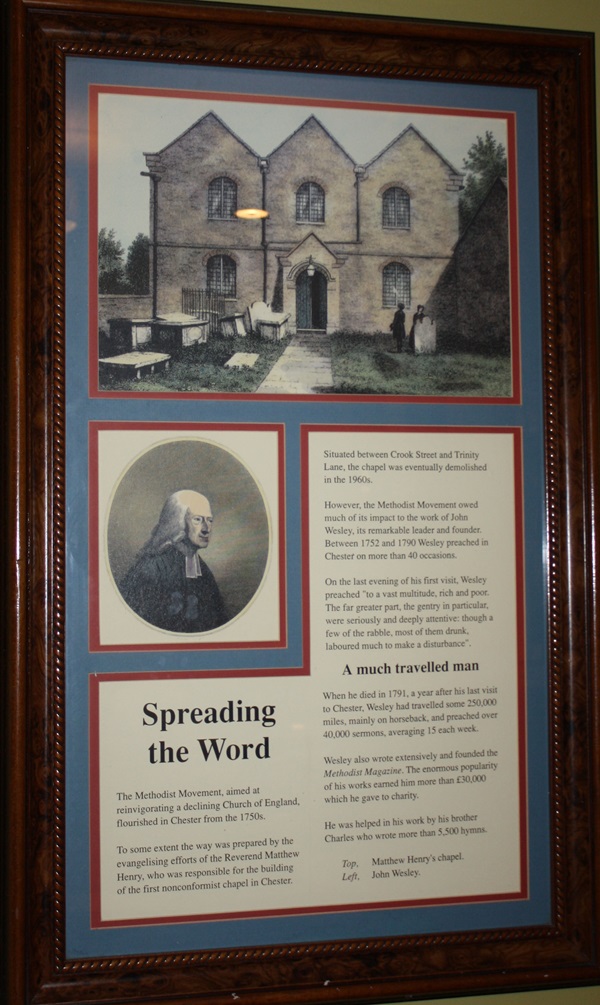

Prints and text about the Methodist Movement and John Wesley.

The text reads: The Methodist Movement, aimed at reinvigorating a declining Church of England, flourished in Chester from the 1750s.

To some extent the way was prepared by the evangelising efforts of the Reverend Matthew Henry, who was responsible for the building of the first nonconformist chapel in Chester.

Situated between Crook Street and Trinity Lane, the chapel was eventually demolished in the 1960s.

However, the Methodist Movement owed much of its impact to the work of John Wesley, its remarkable leader and founder. Between 1752 and 1790 Wesley preached in Chester on more than 40 occasions.

On the last evening of his first visit, Wesley preaches “to a vast multitude, rich and poor. The far greater part, the gentry in particular, were seriously and deeply attentive: through a few of the rabble, most of them drunk, laboured much to make a disturbance”.

When he died in 1791, a year after his last visit to Chester, Wesley had travelled some 250,000 miles, mainly on horseback, and preached over 40,000 sermons, averaging 15 each week.

Wesley also wrote extensively and founded the Methodist Magazine. The enormous popularity of his works earned him more than £30,000 which he gave to charity.

He was helped in his work by his brother Charles who wrote more than 5,500 hymns.

Top: Matthew Henry’s chapel

Left: John Wesley.

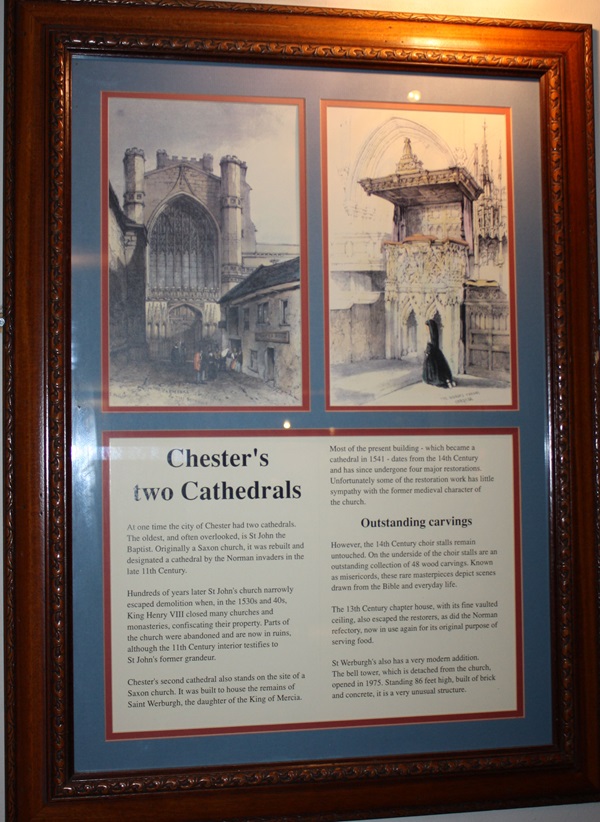

Illustrations and text about Chester’s two cathedrals.

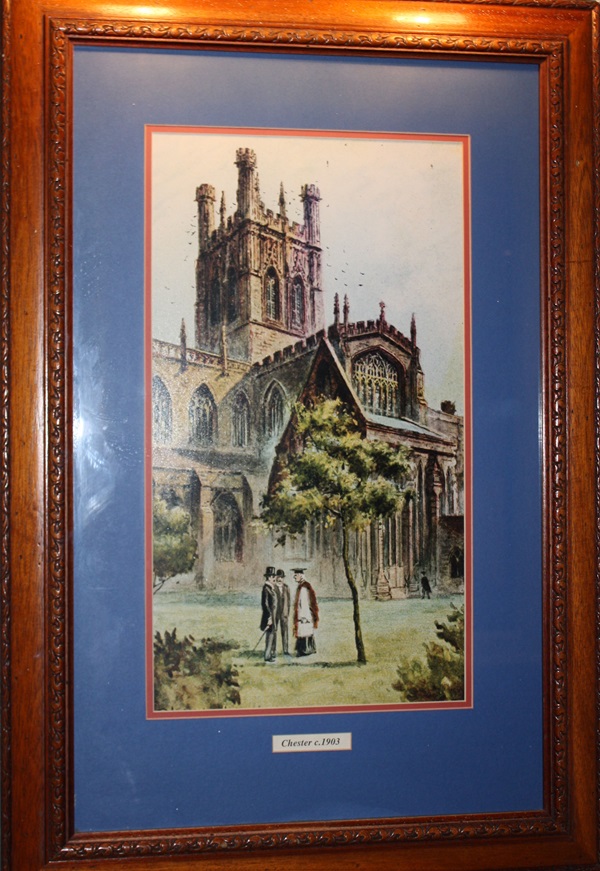

The text reads: At one time the city of Chester had two cathedrals. The oldest, and often overlooked, is St John the Baptist. Originally a Saxon church, it was rebuilt and designated a cathedral by the Norman invaders in the late 11th century.

Hundreds of years later St John’s church narrowly escaped demolition when, in the 1530s and 40s, King Henry VIII closed many churches and monasteries, confiscating their property. Parts of the church were abandoned and are now in ruins, although the 11th century interior testifies to St John’s former grandeur.

Chester’s second cathedral also stands on the site of a Saxon Church. It was built to house the remains of Saint Werburgh, the daughter of the King of Mercia.

Most of the present building – which became a cathedral in 1541 – dates from the 14th century and has since undergone four major restorations. Unfortunately some of the restoration work has little sympathy with the former medieval character of the church.

However, the 14th century choir stalls remain untouched. On the underside of the choir stalls are an outstanding collection of 48 wood carvings. Known as misericords, these rare masterpieces depict scenes drawn from the Bible and everyday life.

The 13th century chapter house, with its fine vaulted ceiling, also escaped the restorers, as did the Norman refectory, now in use again for its original purpose of serving food.

St Werburgh’s also has a very modern addition. The bell tower, which is detached from the church, opened in 1975. Standing 86 feet high, built of brick and concrete, it is a very unusual structure.

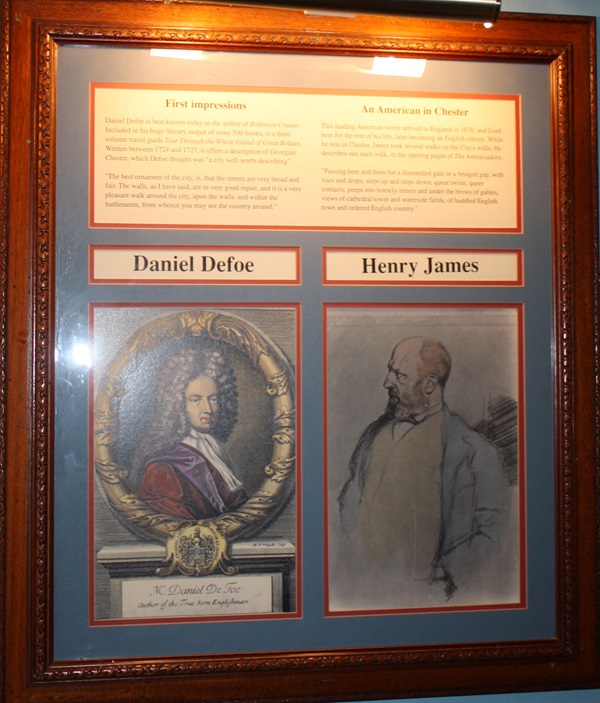

A print, illustration and text about Daniel Defoe and Henry James.

The text reads: Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe is best known today as the author of Robinson Crusoe. Included in his huge literary output of some 500 books, is a three volume travel guide Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain. Written between 1724 and 1727, it offers a description of Georgian Chester, which Defoe thought was “a city well worth describing”.

“The best ornament of the city, is, that the streets are very broad and fair. The walls, as I have said, are in very good repair, and it is a very pleasant walk around the city, upon the walls, and within the battlement, from whence you may see the country around”.

Henry James

This leading American writer arrived in England in 1876, and lived here for the rest of his life, later becoming an English citizen. While he was in Chester, James took several walks on the City’s walls. He describes one such walk, in the opening pages of The Ambassadors.

“Pausing here and there for a dismantled gate or a bridged gap, with rises and drops, steps up and steps down, queer twists, queer contact, peeps into homely streets and under the brows of the gables, views of the cathedral tower and waterside fields, of huddled English town and ordered English country”.

Illustrations and text about The Rows.

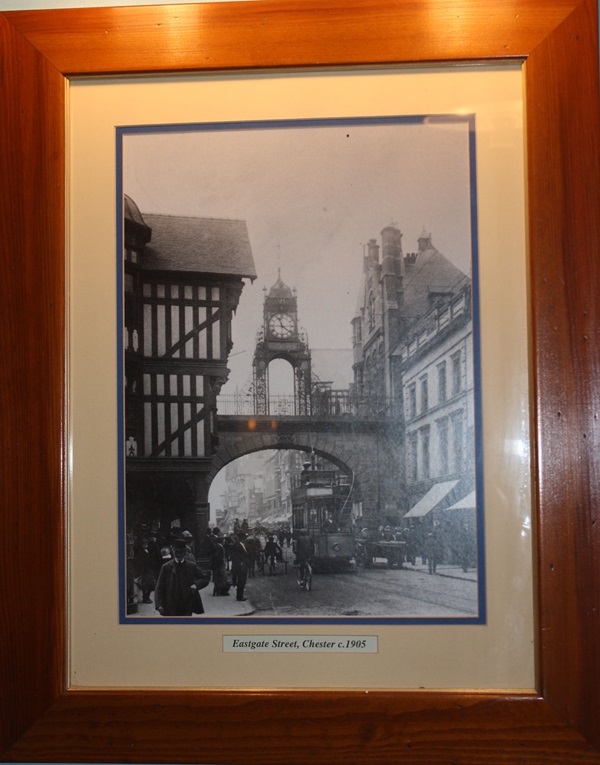

The text reads: Probably Chester’s best known and most photographed sight, the Rows are half-timbered buildings joined by long galleries above street level. The layout of the Rows goes back to the 13th century. There were shops or warehouses at street level, with a long gallery above, reached by steps. The Rows are made up of several linked groups of houses in several streets. The best known examples are in Eastgate, Watergate and Bridge Street.

The gallery level was the living quarters. In the Tudor and Jacobean period the upper floors were built out over the gallery, supported on long poles down to the street level. Shops at ground level used the space between the posts to display their goods to passers-by. The effect is rather like an old world shopping centre.

From top to bottom: Walkway of the Rows on the south side of Watergate, 1852; Watergate Street; Bridge Street and Mercers’ Row, 1777; South end of Northgate Street.

Prints, illustrations and text about The Rows.

The text reads: Chester’s most outstanding architectural feature is The Rows. Dating back to a least the mid 13th century, there is nothing quite like these double-level walkaways in any other English city.

The high distinctive Rows – situated in the centre of Chester – are a series of black and white half-timbered buildings. Now used mainly as shops arranged on two levels, the upper storey is set back by a covered gallery running inside the first floor.

Each building is more or less set out on the same pattern. The ground floor is lower than the street level and is reached by steps. A number of them also have stone crypts. Up above on the first floor there is a gallery with railings behind which is another shop.

Many of the medieval buildings in The Rows were either replaced or heavily restored during the 19th century, retaining the original Tudor style. Some of The Rows were left untouched while others were transformed into shopping arcades.

Top right: Bridge Street Left, Bishop Lloyd’s House, Watergate Street

Right: Gallery in Bridge Street.

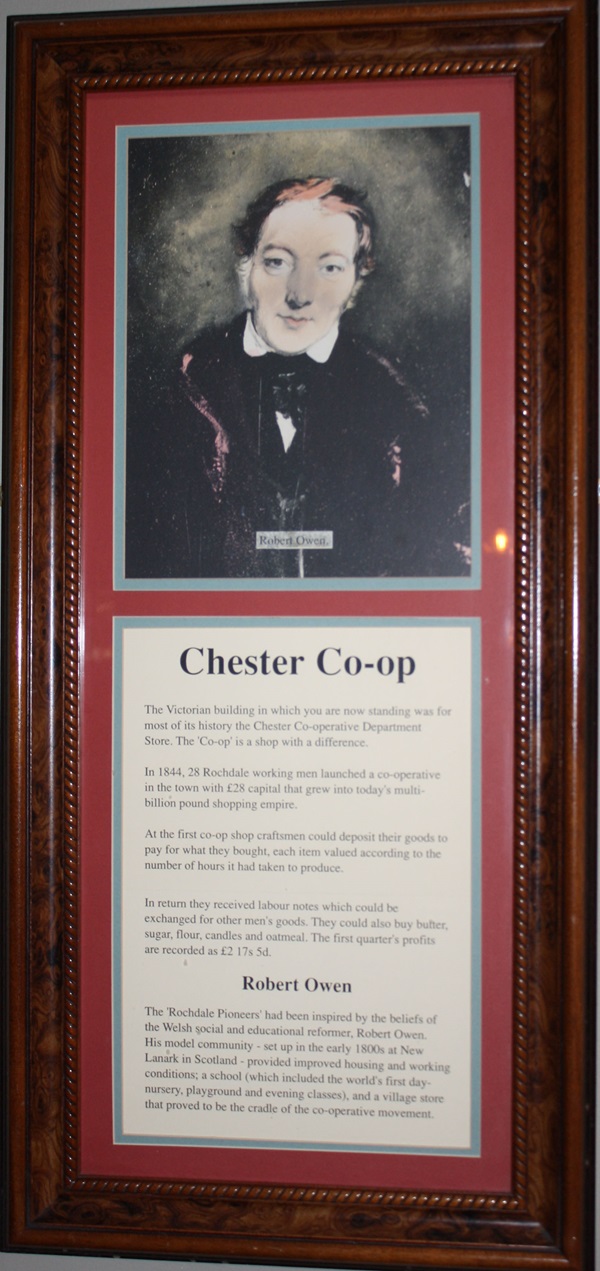

A print and text about Chester Co-op and Robert Owen.

The text reads: Chester Co-op

The Victorian building in which you are now standing was for most of its history the Chester Co-operative Department Store. The ‘Co-op’ is a shop with a difference.

In 1844, 28 Rochdale working men launched a co-operative in the town with £28 capital that grew into today’s multi-billion pound shopping empire.

At the first co-op shop craftsmen could deposit their goods to pay for what they bought, each item valued according to the number of hours it had taken to produce.

In return they received labour notes which could be exchanged for other men’s goods. They could also buy butter, sugar, flour, candles and oatmeal. The first quarter’s profits are recorded as £2 17s 5d.

Robert Owen

The ‘Rochdale Pioneers’ had been inspired by the beliefs of the Welsh social and educational reformer, Robert Owen. His model community – set up in the early 1800s at New Lanark in Scotland – provided improved housing and working conditions; a school (which included the words first day-nursery, playground and evening classes), and a village store that proved to be the cradle of the co-operative movement.

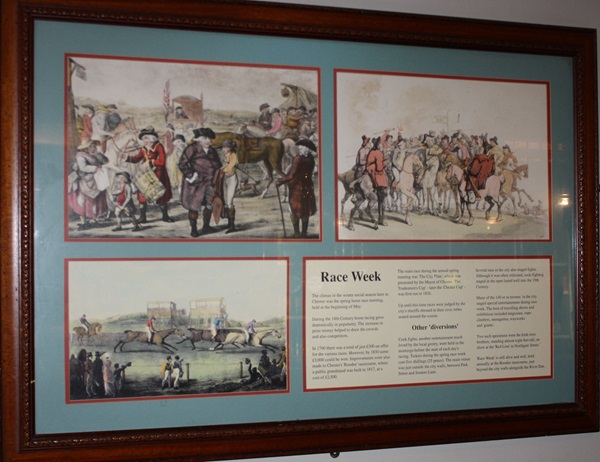

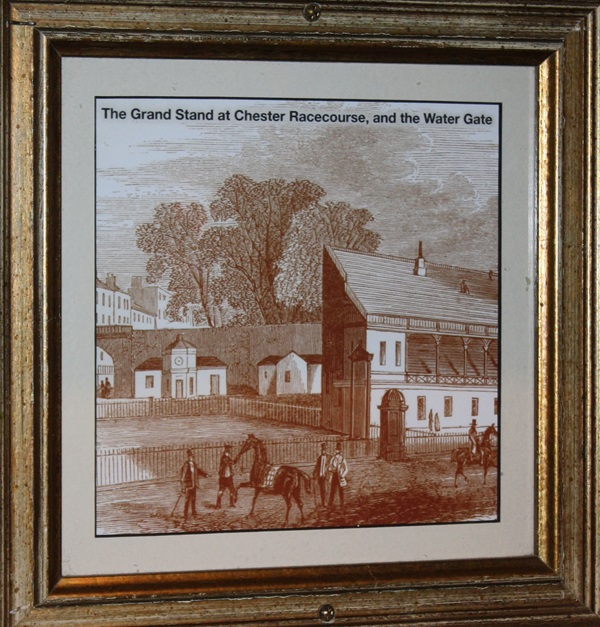

Prints, illustrations and text about racing at Chester.

The text reads: The climax to the winter social season here in Chester was the spring horse race meeting, held at the beginning of May.

During the 18th century horse racing grew dramatically in popularity. The increase in prize money helped to draw the crowds and also competitors.

In 1760 there was a total of just £300 on offer for the various races. However, by 1830 some £3,000 could be won. Improvements were also made to Chester’s ‘Roodee’ racecourse, where a public grandstand was built in 1817, at a cost of £2,500.

The main race during the annual spring meeting was ‘The City Plate’, which was presented by the Mayor of Chester. ‘The Tradesman Cup’ – later the ‘Chester Cup’ – was first run in 1824.

Up until this time races were judged by their city’s sheriffs dressed in the civic robes seated around the course.

Cock fights, another entertainment much loved by the local gentry, were held in the mornings before the start of each day’s racing. Tickets during the spring race week cost 5 shillings (25 pence). The main venue was just outside the city walls, between Park Street and Souters Lane.

Several inns in the city also staged fights. Although it was often criticised, cock-fighting staged in the open lasted well into the 19th century.

Many of the 140 or so taverns in the city staged special entertainments during race week. The host of travelling shows and exhibitions included magicians, rope-climbers, menageries, waxworks and ‘giants’.

Two such specimens were Irish twin brothers, standing almost eight feet tall, on show at the ‘Red Lion’ in Northgate Street.

‘Race Week’ is still alive and well, held annually at the Roodee Racecourse, just beyond the city walls alongside the River Dee.

An illustration of the Grand Stand and Chester Racecourse, and the Water Gate.

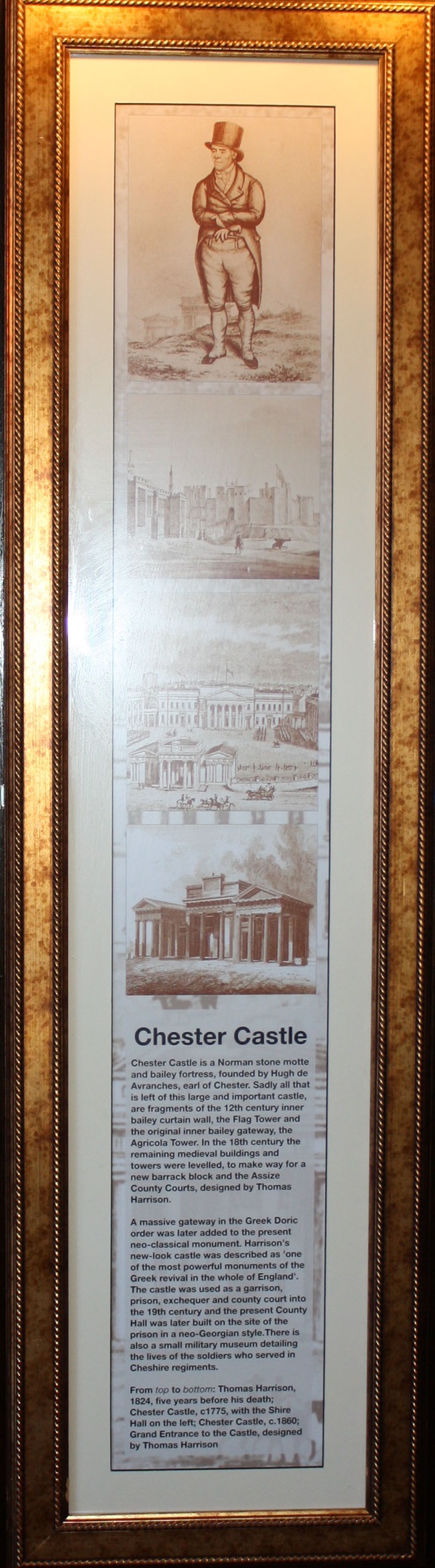

Illustrations and text about Chester Castle.

The text reads: Chester Castle is a Norman stone motte and bailey fortress, founded by Hugh de Avranches, Earl of Chester. Sadly all that is left of this large and important castle are fragments of the 12th century inner bailey curtain wall, the Flag Tower and the original inner bailey gateway, the Agricola Tower. In the 18th century the remaining medieval buildings and towers were levelled, to make way for a new barrack block and the Assize County Courts, designed by Thomas Harrison.

A massive gateway in the Greek Doric order was later added to the present neo-classical monument. Harrison’s new-look castle was described as ‘one of the most powerful monuments of the Greek revival in the whole of England’. The castle was used as a garrison, prison, exchequer and county court into the 19th century and the present County Hall was later built on the site of the prison in a neo-Georgian style. There is also a small military museum detailing the lives of the soldiers who served in Cheshire regiments.

From top to bottom: Thomas Harrison, 1824, five years before his death; Chester Castle, c1775, with the Shire Hall on the left; Chester Castle, c1860; Grand Entrance to the Castle, designed by Thomas Harrison.

Photographs of Roman tombstones discovered in Chester.

Above: Tombstone to Caecillius Avitus

Below: Roman Tombstone in memory of Marcus Aurelius Nepos.

Illustrations of the County Gaol.

Above: View across the River Dee towards the County Gaol and the Castle, 1817

Below: Fishing for salmon in the River Dee, in front of the County Gaol.

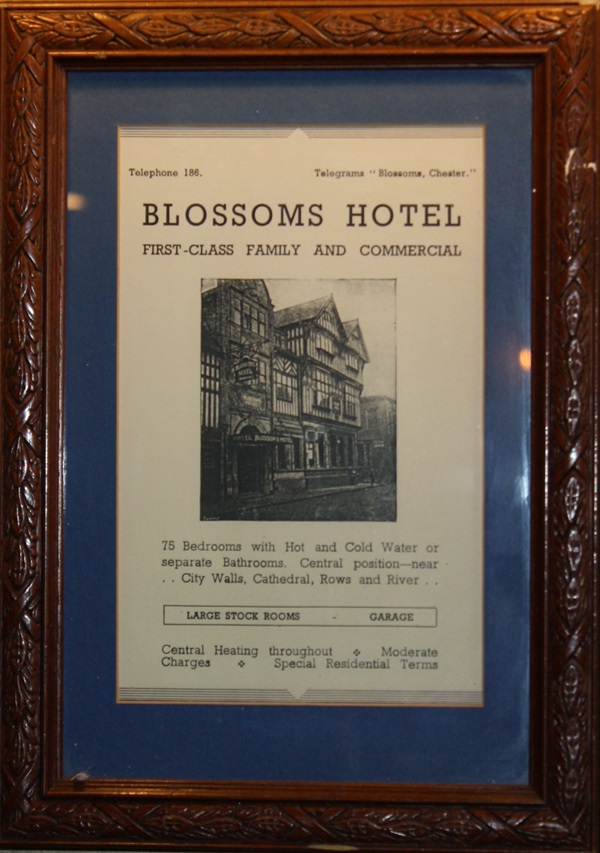

An old poster for Blossoms Hotel.

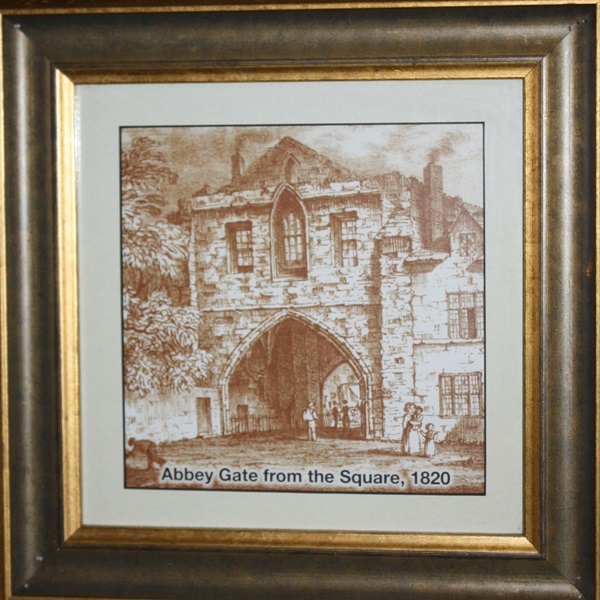

An illustration of Abbey Gate from the Square, 1820.

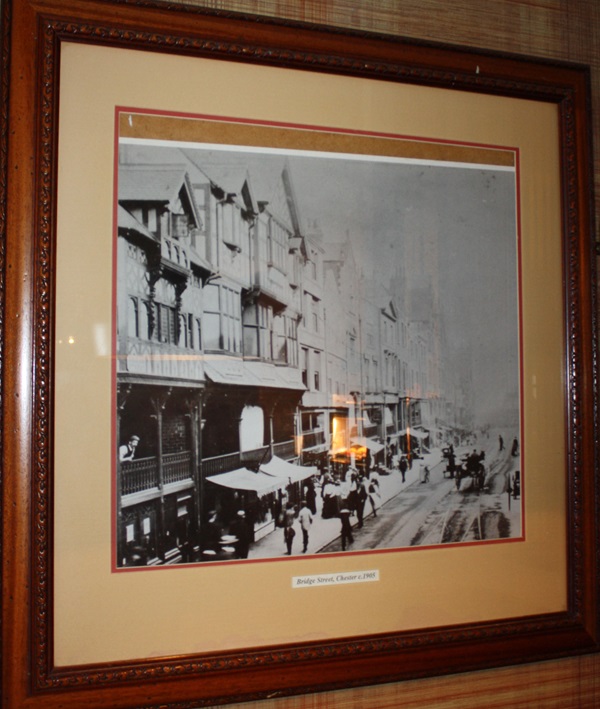

A photograph of Bridge Street, Chester, c1905.

A photograph of Eastgate Street, Chester, c1905.

A painting of Chester, c1903.

A photograph of Northgate Street, Chester, c1903.

Illustrations of Northgate.

Above: Northgate and Bluecoat Hospital

Below: Northgate Street

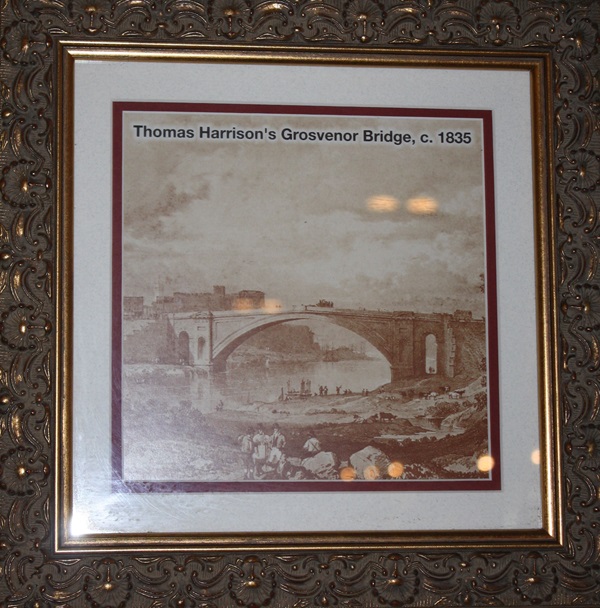

An illustration of Thomas Harrison’s Grosvenor Bridge, c1835.

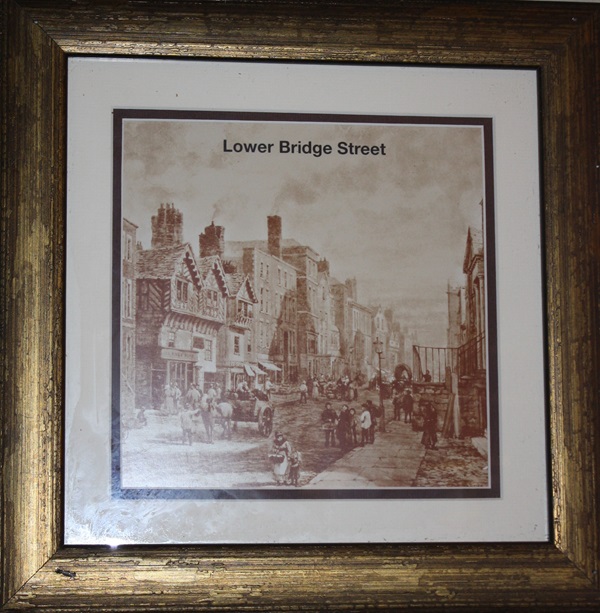

An illustration of Lower Bridge Street.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk