The china clay industry has long dominated the landscape around St Austell and the livelihood of its residents. Most of the mines were in the Higher Quarter, or Rann Wartha, to give it its Cornish name. For more than 70 years, until its closure in 2005, these premises housed the St Austell Conservative Club. The oldest part was built in the early 19th century, when there were warehouses in Biddick’s Court connected with the china clay industry.

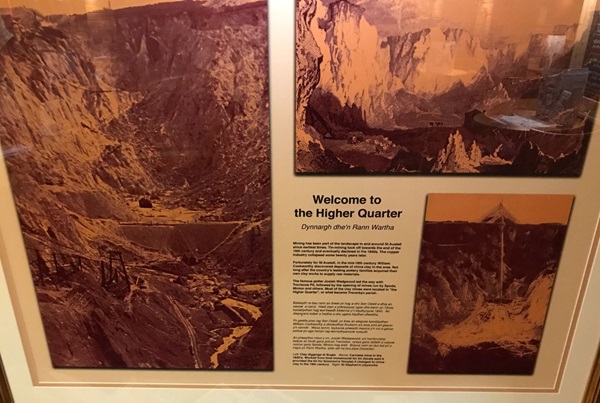

Illustrations and text about Rann Wartha.

The text reads: Mining has been part of the landscape in and around St Austell since earliest times. Tin-mining took off towards the end of the 16th century and eventually declined in the 1840s. The copper industry collapsed some twenty years later.

Fortunately for St Austell, in the mid-18th century William Cookworthy discovered deposits of china clay in the area. Not long after the country’s leading pottery families acquired their own clay works to supply raw materials.

The famous potter Josiah Wedgewood led the way with Treviscoe Pit, followed by the opening of mines run by Spode, Minton and others. Most of the clay mines were located in “the Higher Quarter”, or what became Treverbyn parish.

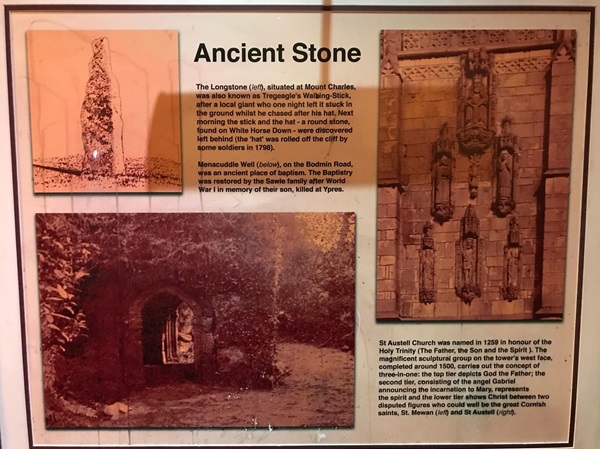

An illustration, photographs and text about ancient stone in the area.

The text reads: The Longstone (left), situated at Mount Charles, was also known as Tregeagle’s Walking-Stick, after a local giant who one night left it stuck in the ground whilst he chased after his hat. Next morning the stick and the hat – a round stone, found on White Horse Down – were discovered left behind (the ‘hat’ was rolled off the cliff by some soldiers in 1798).

Menacuddle Well (below), on the Bodmin Road, was an ancient place of baptism. The Baptistery was restored by the Sawle family after World War I in memory of their son, killed at Ypres.

St Austell Church was named in 1259 in honour of the Holy Trinity (The Father, the son and the Spirit). The magnificent sculptural group on the tower’s west face, completed around 1500, carries out the concept of three-in-one: the top tier depicts God the Father; the second tier, consisting of the angel Gabriel announcing the incarnation to Mary, represents the spirit and the lower tier shows Christ between two disputed figures who could well be the great Cornish saints, St Mewan (left) and St Austell (right).

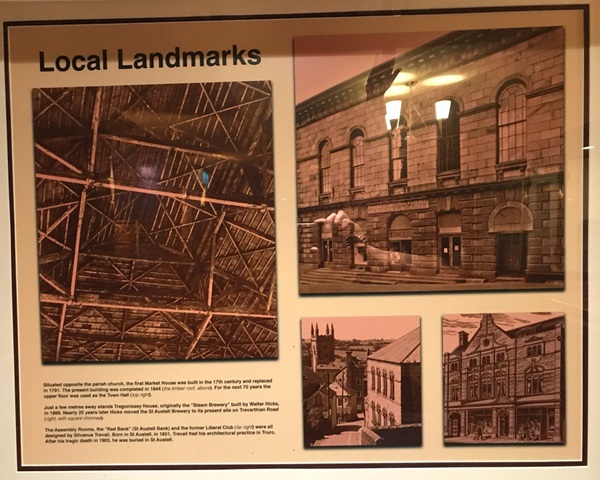

An illustration, photographs and text about local landmarks.

The text reads: Situated opposite the parish church, the first Market House was built in the 17th century and replaced in 1791. The present building was completed in 1844 (the timber roof, above). For the next 70 years the upper floor was used as the Town Hall (top right).

Just a few metres away stands Tregonissey House, originally the Steam Brewery built by Walter Hicks, in 1869. Nearly 25 years later Hicks moved to Austell brewery to its present site on Trevarthian Road (right, with square chimney).

The Assembly Rooms, the Red Bank (St Austell Bank) and the former Liberal Club (far right) were all designed by Silvanus Trevail. Born in St Austell, in 1851, Trevail had his architectural practice in Truro. After his tragic death in 1903, he was buried in St Austell.

Prints and text about the changes in St Austell.

The text reads: Number 9 Biddick’s Court – the building that you are now in – was the home of the St Austell Conservative Club for more than 70 years, until its closure in October 2005.

The oldest part of the premises was built between c1813 and 1840. Around this time Biddick’s Court accommodated warehouses connected with the china clay industry, such as the one owned by John Lovering & Company.

Biddick’s Court was also home to the offices of the Local Board, which ran the town until the Urban District Council was formed in 1897. Approached by Fore Street, Biddick’s Court takes its name from a Doctor Biddick, who, rather curiously, is sad to have visited his patients after dark.

Left: Fore Street, 1898. The line of men and boys in the street is almost outside the alleyway to Biddick’s Court.

Above centre: William Luke in the doorway of his Booksellers and printers at 12 Fore Street, with its distinctive projecting upper storeys.

Above right: This end of Fore Street, c1830

Right: Fore Street, c1910.

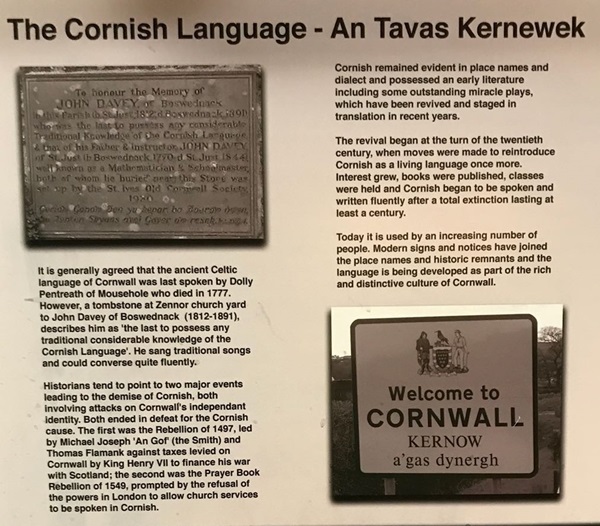

Photographs and text about the Cornish language.

The text reads: It is generally that the ancient Celtic language of Cornwall was last spoken by Dolly Pentreath of Mousehole who died in 1777. However, a tombstone at Zennor church yard to John Davey of Boswednack (1812-91), describes him as ‘the last to possess any traditional considerable knowledge of the Cornish Language’. He sang traditional songs and could converse quite fluently.

Historians tend to point to two major events leading to the demise of Cornish, both involving attacks on Cornwall’s independent identity. Both ended in defeat for the Cornish cause. The first was the Rebellion of 1497, led by Michael Joseph ‘An Gof’ (the Smith) and Thomas Flamank against taxes levied on Cornwall by King Henry VII to finance his war with Scotland; the second was the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, prompted by the refusal of the powers in London to allow church services to be spoken in Cornish.

Cornish remained evident in place names and dialect and possessed an early literature including some outstanding miracle plays, which have been revived and stages in translation in recent years.

The revival began at the turn of the twentieth century, when moves were made to reintroduce Cornish as a living language once more. Interest grew, books were published, classes were held and Cornish began to be spoken and written fluently after a total extinction lasting at least a century.

Today it is used by an increasingly number of people. Modern signs and notices have joined the place names and historic remnants and the language is being developed as part of the rich and distinctive culture of Cornwall.

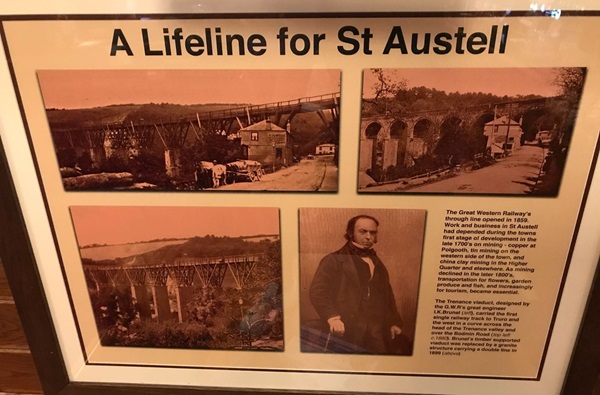

Photographs and text about the Great Western railway.

The text reads: The Great Western Railway’s through line opened in 1859. Work and business in St Austell had depended during the town’s first stage of development in the late 1700s on mining – copper at Polgooth, tin mining on the western side of the town, and china clay mining in the Higher Quarter and elsewhere. As mining declined in the later 1800s, transportation for flowers, garden produce and fish, and increasingly for tourism, became essential.

The Trenance viaduct, designed by the GWR’s great engineer IK Brunel (left), carried the first single railway track to Truro and the west in a curve across the head of the Trenance valley and over the Bodmin Road (top left, c1880). Brunel’s timber supported viaduct was replaced by a granite structure carrying a double line in 1899 (above).

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk