George Orwell’s fictitious, ideal pub, ‘Moon Under Water’, was famously described in a newspaper article. This one was a former garage and showroom built in 1929 on the site of Cambray Pavilion. The pavilion was built before 1806 for James King, who entertained royal guests at his home. The Regency-style house had 10 bedrooms and a large garden – which is now Sandford Park.

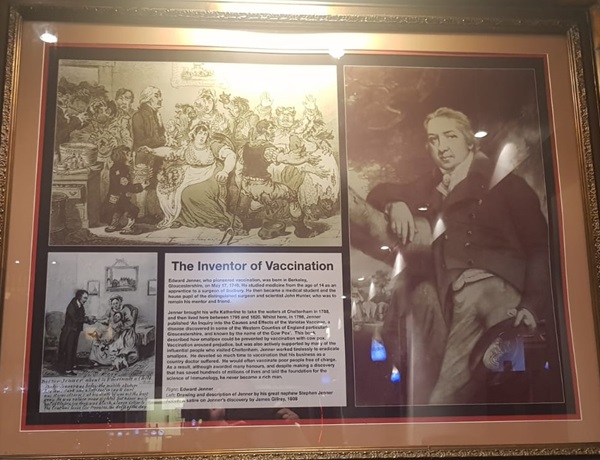

Illustrations, a print and text about Edward Jenner.

The text reads: Edward Jenner, who pioneered vaccination, was born in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, on May 17, 1749. He studied medicine from the age of 14 as an apprentice to a surgeon of Sodbury. He then became a medical student and the house pupil of the distinguished surgeon and scientist John Hunter, who was to remain his mentor and friend.

Jenner brought his wife Katherine to take the waters at Cheltenham in 1788, and then lived here between 1795 and 1820. Whilst here, in 1798, Jenner published ‘An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the Western Counties of England particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the ‘Cow Pox’. This book described how smallpox could be prevented by vaccination with cow pox. Vaccination aroused prejudice, but was also actively supported by many of the influential people who visited Cheltenham. Jenner worked tirelessly to eradicate smallpox. He devoted so much time to vaccination that his business as a country doctor suffered. He would often vaccinate poor people free of charge. As a result, although awarded many honours, and despite making a discovery that has saved hundreds of millions of lives and laid the foundation for the science of Immunology, he never became a rich man.

Right: Edward Jenner

Left: Drawing and description of Jenner by his great nephew Stephen Jenner

Above: A satire on Jenner’s discovery by James Gillray, 1808.

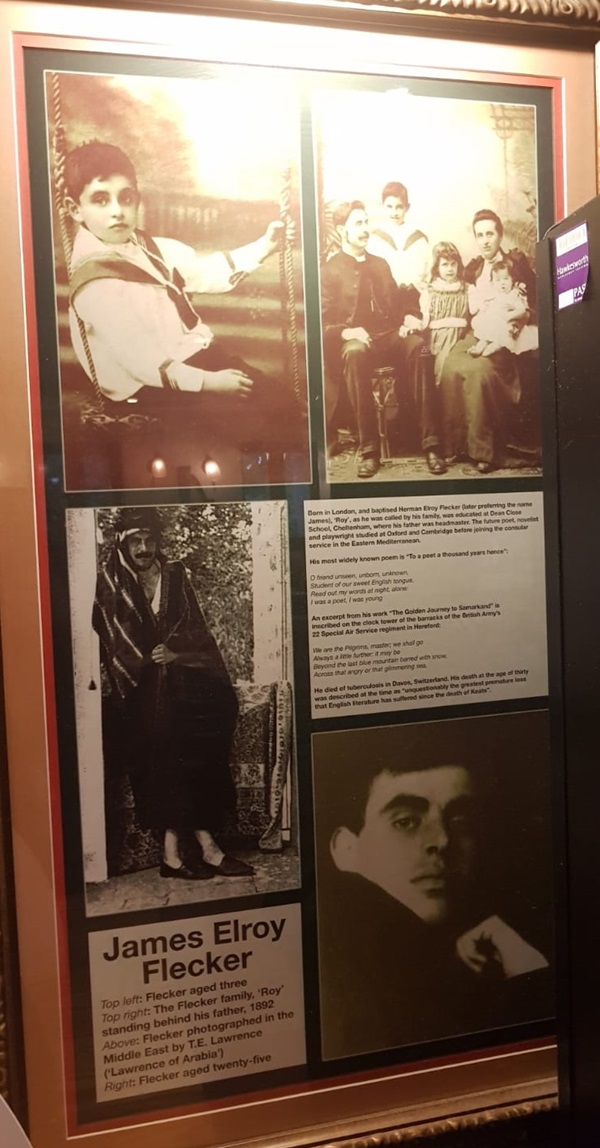

Photographs and text about Herman Elroy Flecker.

The text reads: Born in London, and baptised Herman Elroy Flecker (later preferring the name James), ‘Roy’, as he was called by his family, was educated at Dean Close School, Cheltenham, where his father was headmaster. The future poet, novelist and playwright studied at Oxford and Cambridge before joining the consular service in the Eastern Mediterranean.

His most widely known poem is To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence.

O friend unseen, unborn, unknown

Student of our sweet English tongue

Read out my words at night, alone:

I was a poet, I was young

An excerpt from his work The Golden Journey to Samarkand is inscribed on the clock tower of the barracks of the British Army’s 22 Special Air Service regiment in Hereford:

We are the Pilgrims, master; we shall go

Always a little further: it may be

Beyond the last blue mountain barred with snow,

Across that angry or that glimmering sea.

He died of tuberculosis in Davos, Switzerland. His death at the age of thirty was described at the time as “unquestionably the greatest premature loss that English literature has suffered since the death of Keats.”

Prints and text about spas and wells in the area.

The text reads: The visit of King George III to Skillicorne’s Well, in 1788, prompted hordes of fashionable visitors to come to Cheltenham to take the waters. The King’s condition, however, was not improved. In fact it seems that the effect of the water was largely laxative.

Entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to make fortunes. During the following half century, half a dozen major spas and a number of smaller wells were set up. These included the Montpellier and Pittville spas, as well as the grander named Royal Well and Imperial Spa.

There were also Pump Rooms. One of the most elaborate, featuring a ballroom, billiard room, and library, was built at Pittville in the 1820s.

The major establishments featured walks and gardens, lavishly provided with pavilions, pagodas, bandstands, and fountains.

Cheltenham owes its fine parks and open spaces to the demands of its 19th century visitors. Green areas, now built over, included Jessop’s Nursery, which featured botanical gardens and a zoo and Cypher’s Exotic Nurseries, near Lansdown Station. Sandford Park – situated to the rear of this Wetherspoon pub – was a later addition, opening in 1927.

Top: George III taking the waters, 1788

Centre: Montpelier Gardens, 1836

Above: Cheltenham Spa, 1748

Left: The Pittville Pump Room, 1834.

Illustrations and text about the races.

The text reads: Cheltenham is the home of National Hunt racing, and its racecourse is the country’s leading steeplechase venue.

The town’s earliest race meetings were held on Nottingham Hill and Cleeve Hill in the early 19th century. The famous Gold Cup was first staged in 1819, and its attraction was such that within a few years it drew crowds of up to 50,000.

However, the preaching of the charismatic “Pope of Cheltenham”, Francis Close, inspired the burning down of the grandstand in 1830. Lord Ellenburgh offered an alternative venue at Prestbury Park, which has been used almost continuously since then.

The highlight of the season is the National Hunt Festival, held in March. During those three days, the population of the town doubles, with a strong Irish representation of both race-goers and horses.

One of the great jockeys of all time, Fred Archer, was born in St George’s Place, Cheltenham in 1857. In a 16-year career, he won 22 Classic races, including five Derby victories.

At the age of 17, he became England’s Champion Jockey, a position he held for the rest of his life. In the 1885 season he rode 246 winners, a record which stood until 1933.

Worn out by a “wasting diet” in an effort to keep his weight low, and undermined by the death of his wife, Archer shot himself in 1886 whilst delirious with typhoid fever.

Above, left: The first steeple chase on record

Above, right: The Betting Post

Below, right: On the course

Left: Fred Archer

Right: Fred Archer and Lord Falmouth.

Prints and text about Gustav Holst.

The text reads: Gustav Holst was born in Cheltenham in 1874. A plaque on his birthplace in Clarence Road, now the Gustav Holst Museum, was unveiled in 1949 by another great English composer, Holst’s lifelong friend Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Holst’s father, of Swedish descent, was the organist at All Saints’ Church. When the four year-old Gustav heard his father perform a piece he was learning on the piano he called out “That’s my tune!”. He later sang in the church choir and played in his father’s orchestra.

Holst learned the trombone and violin as well as the piano. After studying at the Royal College of Music, he joined the Carl Rosa Opera Company and later the Scottish Orchestra. He worked for many years as musical director at various schools and colleges amongst them St Paul’s Girls’ School, after which he named his 1913 suite for string orchestra.

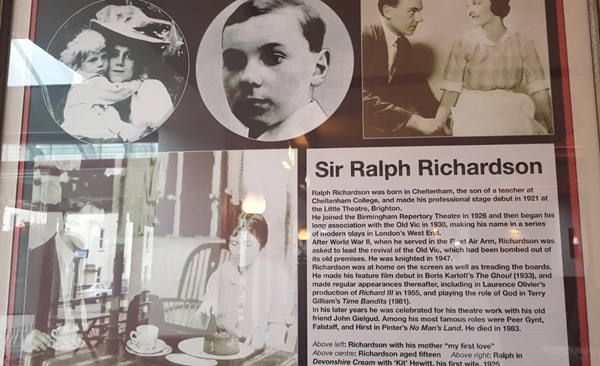

Photographs and text about Sir Ralph Richardson.

The text reads: Ralph Richardson was born in Cheltenham, the son of a teacher at Cheltenham College, and made his professional stage debut in 1921 at the Little Theatre, Brighton.

He joined the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1926 and then began his long association with the Old Vic in 1930, making his name in a series of modern plays in London’s West End.

After World War II, when he served in the Fleet Air Arm, Richardson was asked to lead the revival of the Old Vic, which had been bombed out of its old premises. He was knighted in 1947.

Richardson was at home on the screen as well as treading the boards. He made his feature film debut in Boris Karloff’s The Ghoul (1933), and made regular appearances thereafter, including in Laurence Olivier’s production of Richard III in 1955, and playing the role of God in Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981).

In his later years he was celebrated for his theatre work with his old friend John Gielgud. Among his most famous roles were Peer Gynt, Falstaff, and Hirst in Pinter’s No Man’s Land. He died in 1983.

Above left: Richardson with his mother “my first love”

Above centre: Richardson aged fifteen

Above right: Ralph in Devonshire Cream with ‘Kit’ Hewitt, his first wife, 1925

Left: In The Farmer’s Wife, 1925.

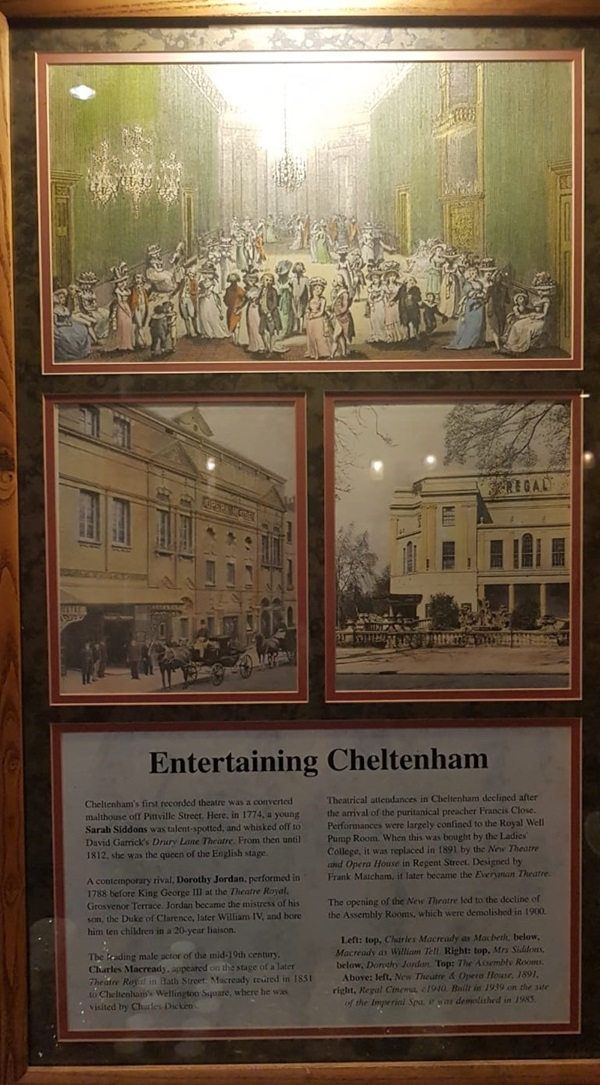

Illustrations and text about entertaining Cheltenham.

The text reads: Cheltenham’s first recorded theatre was a converted Malthouse off Pittville Street. Here, in 1774, a young Sarah Siddons was talent-spotted, and whisked off to David Garrick’s Drury Lane Theatre. From then until 1812, she was the queen of the English stage.

A contemporary rival, Dorothy Jordan, performed in 1788 before King George III at the Theatre Royal, Grosvenor Terrace. Jordan became the mistress of his son, the Duke of Clarence, later William IV, and bore him ten children in a 20-year liaison.

The leading male actor of the mid-19th century, Charles Macready, appeared on the stage of a later Theatre Royal in Bath Street. Macready retired in 1851 to Cheltenham’s Wellington Square, where he was visited by Charles Dickens.

Theatrical attendances in Cheltenham declined after the arrival of the puritanical preacher Francis Close. Performances were largely confined to the Royal Well Pump Room. When this was bought by the Ladies’ College, it was replaced in 1891 by the New Theatre and Opera House in Regent Street. Designed by Frank Matcham, it later became the Everyman Theatre.

The opening of the New Theatre left to the decline of the Assembly Rooms, which were demolished in 1900.

Left, top: Charles Macready as Macbeth

Below: Macready as William Tell

Right, top: Mrs Siddons

Below: Dorothy Jordan

Top: The Assembly Rooms

Above, left: New Theatre & Opera House, 1891

Right: Regal Cinema, c1940 built in 1939 on the site of the Imperial Spa, it was demolished in 1985.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk