The first meeting of the Southampton Dock Company (on 16 August 1836) agreed to buy mud land next to the town quay to build Southampton’s first dock. The foundation stone for the open (or tidal) dock was laid on 12 October 1838 by Admiral Sir Lucius Curtis, later appointed Admiral of the Fleet. The ceremony was watched by more than 20,000 people, including the Mayor of Southampton.

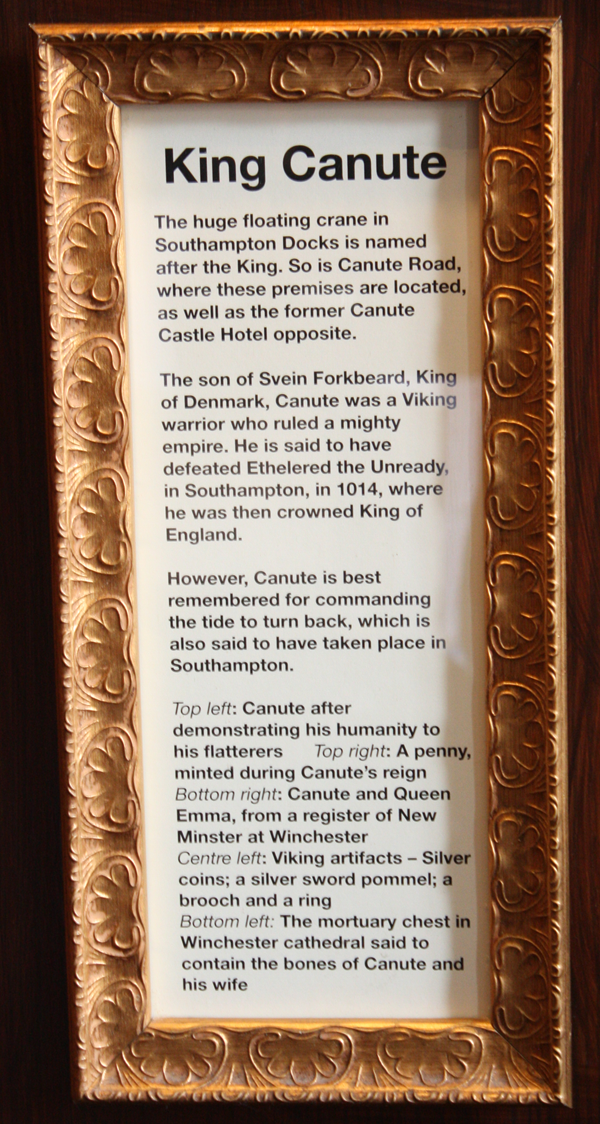

A framed passage about King Canute.

The text reads: The huge floating crane in Southampton Docks is named after the King. So is Canute Road, where these premises are located, as well as the former Canute Castle Hotel opposite.

The son of Svein Forkbeard, King of Denmark, Canute was a Viking warrior who ruled a mighty empire. He is said to have defeated Ethelered the Unready, in Southampton, in 1014, where he was then crowned King of England.

However, Canute is best remembered for commanding the tide to turn back, which is also said to have taken place in Southampton.

Top left: Canute after demonstrating his humanity to his flatterers Top right: A penny, minted during Canute’s reign

Bottom right: Canute and Queen Emma, from a register of New Minster at Winchester

Centre left: Viking artefacts – Silver coins; a silver sword pommel; a brooch and a ring

Bottom left: The mortuary chest in Winchester cathedral said to contain the bones of Canute and his wife.

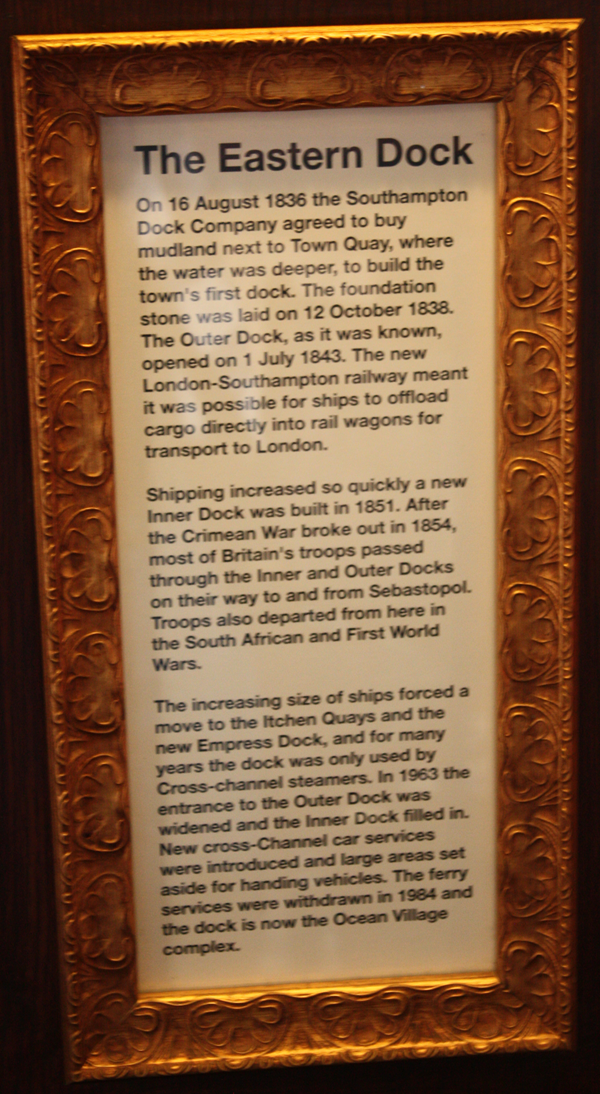

A framed passage about the Eastern Dock.

The text reads: On 16 August 1836 the Southampton Dock Company agreed to buy mudland next to Town Quay, where the water was deeper, to build the town’s first dock. The foundation stone was laid on 12 October 1838. The Outer Dock, as it was known, opened on 1 July 1843. The new London-Southampton railway meant it was possible for ships to offload cargo directly into rail wagons for transport to London.

Shipping increased so quickly a new Inner Dock was built in 1851. After the Crimean War broke out in 1854, most of Britain’s troops passed through the Inner and Outer Docks on their way to and from Sebastopol. Troops also departed from here in the South African and First World Wars.

The increasing size of ships forced a move to the Itchen Quays and the new Empress Dock, and for many years the dock was only used by Cross-channel steamers. In 1963 the entrance to the Outer Dock was widened and the Inner Dock filled in. New cross-Channel car services were introduced and large areas set aside for handling vehicles. The ferry services were withdrawn in 1964 and the dock is now the Ocean Village complex.

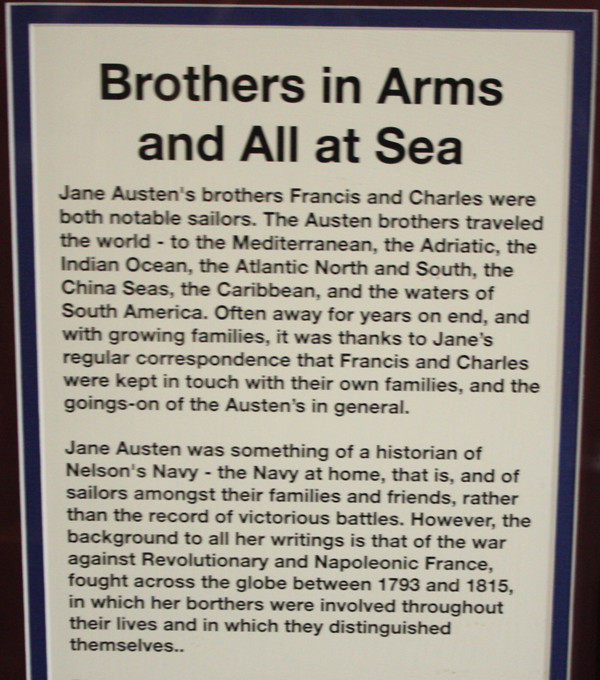

A framed passage about Jane Austen, and her brothers.

The text reads: Jane Austen’s brothers Francis and Charles were both notable sailors. The Austen brothers travelled the world – to the Mediterranean, the Adriatic, the Indian Ocean, the Atlantic North and South, the China Seas, the Caribbean, and the waters of South America. Often away for year on end, and with growing families, it was thanks to Jane’s regular correspondence that Francis and Charles were kept in touch with their own families, and the goings-on of the Austen’s in general.

Jane Austen was something of a historian of Nelson’s Navy – the Navy at home, that is, and of sailors amongst their families and friends, rather than the record of victorious battles. However, the background to all her writings is that of the war again Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, fought across the globe between 1793 and 1815, in which her brothers were involved throughout their lives and in which they distinguished themselves ..

Pictures, from top to bottom: Captain Charles Austen; Rear-Admiral Charles Austen; Captain Francis Austen; Vice-Admiral Sir Francis Austen.

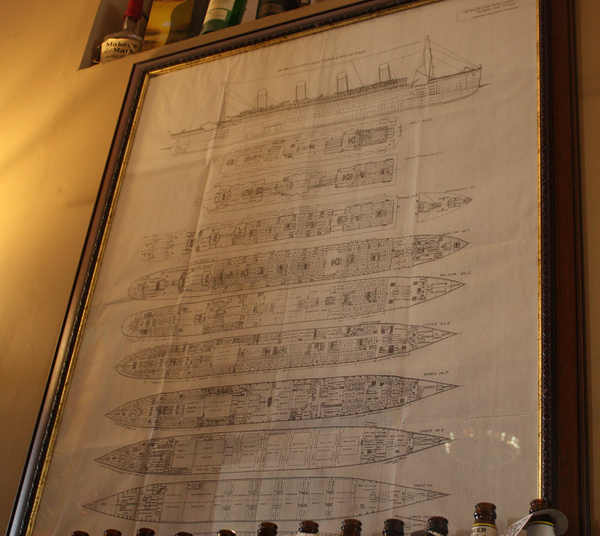

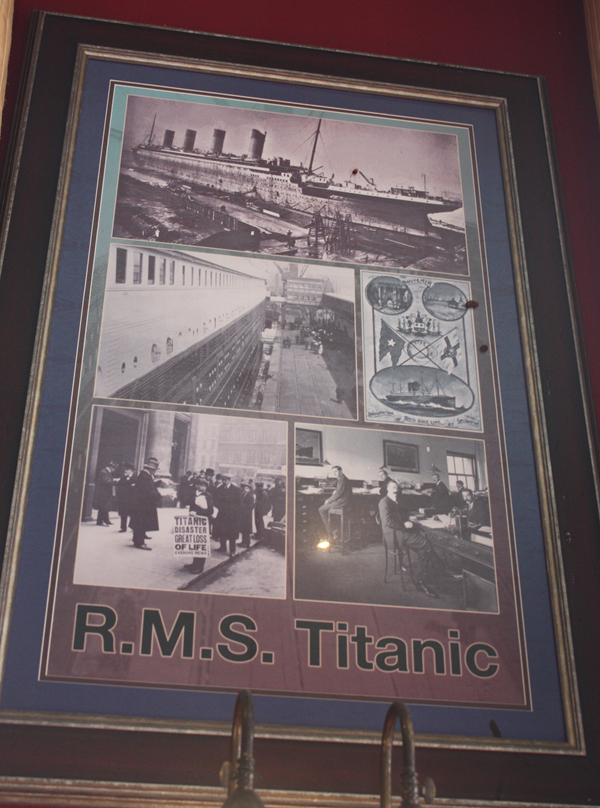

A framed copy of a plan of the Titanic.

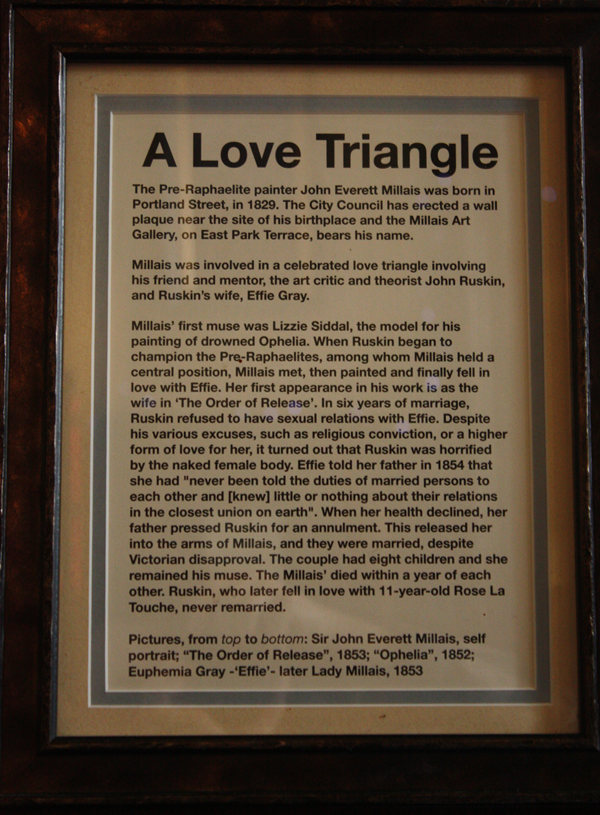

A framed passage about John Everett Millais.

The text reads: The Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais was born in Portland Street, in 1829. The City Council has erected a wall plaque near the site of his birthplace and the Millais Art Gallery, on East Park Terrace, bears his name.

Millais was involved in a celebrated love triangle involving his friend and mentor, the art critic and theorist John Ruskin, and Ruskin’s wife, Effie Gray.

Millais’ first muse was Lizzie Siddal, the model for his painting of drowned Ophelia. When Ruskin began to champion the Pre-Raphaetlites, among whom Millais held a central position, Millais met, then painted and finally fell in love with Effie. Her first appearance in his work is as the wife in ‘The Order of Release’. In six years of marriage, Ruskin refused to have sexual relations with Effie. Despite his various excuses, such as religious conviction, or a higher form of love for her, it turned out that Ruskin was horrified by the naked female body. Effie told her father in 1854 that she had “never been told the duties of married persons to each other (knew) little or nothing about their relations in the closest union on earth”. When her health declined, her father pressed Ruskin for an annulment. This released her into the arms of Millais, and they were married, despite Victorian disapproval. The couple had eight children and she remained his muse. The Millais’ died within a year of each other. Ruskin, who later fell in love with 11-year-old Rose La Touche, never remarried.

Pictures, from top to bottom; Sir John Millais, self portrait; “The Order of Release”, 1853; “Ophelia”, 1852; Euphemia Gray – “Effie” – later Lady Millais, 1853

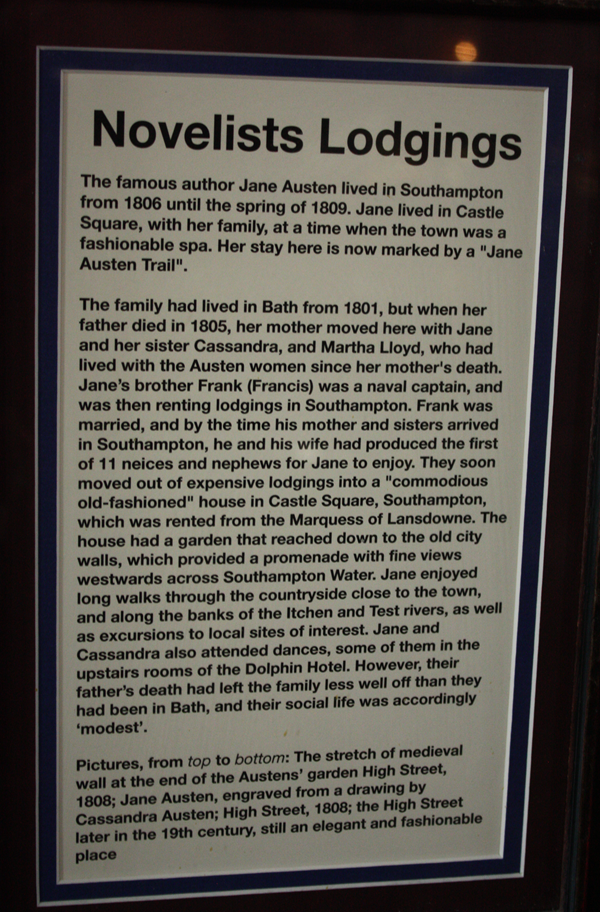

A framed passage about Jane Austen.

The text reads: The famous author Jane Austen lived in Southampton from 1806 until the sprint of 1809. Jane lived in Castle Square, with her family, at a time when the town was a fashionable spa. Her stay here is now marked by a “Jane Austen Trail”.

The family had lived in Bath from 1801, but when her father died in 1805, her mother moved here with Jane and her sister Cassandra, and Martha Lloyd, who had lived with the Austen women since her mother’s death. Jane’s brother Frank (Francis) was a naval captain, and was then renting lodgings in Southampton. Frank was married, and by the time his mother and sisters arrived in Southampton, he and his wife had produced the first of 11 nieces and nephews for Jane to enjoy. They soon moved out of expensive lodgings into a “commodious old-fashioned” house in Castle Square, Southampton, which was rented from the Marquess of Lansdowne. The house had a garden that reached down to the old city walls, which provided a promenade with fine views westwards across Southampton Water. Jane enjoyed long walks through the countryside close to the town, and along the banks of the Itchen and Test rivers, as well as excursions to local sites of interest. Jane and Cassandra also attended dances, some of them in the upstairs rooms of the Dolphin Hotel. However, their father’s death had left the family less well off than they had been in Bath, and their social life was accordingly ‘modest’.

Pictures, from top to bottom: the stretch of medieval wall at the end of the Austen’s’ garden High Street, 1808: Jane Austen, engraved from a drawing by Cassandra Austen; High Street, 1808; the High Street later in the 19th century, still an elegant and fashionable place.

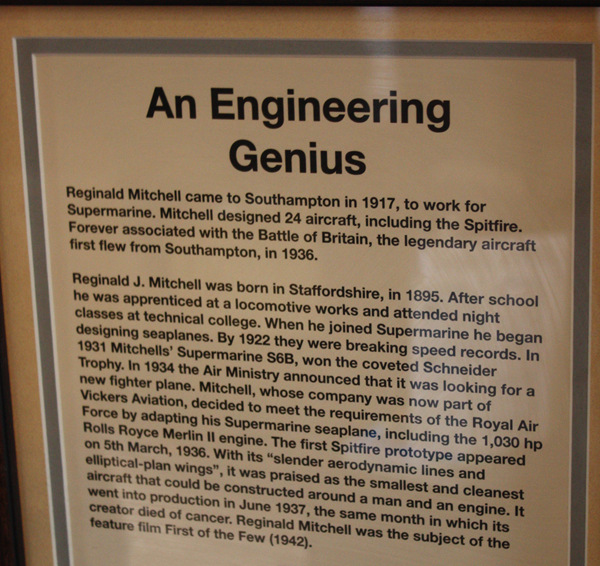

A framed passage about Reginald Mitchell.

The text reads: Reginald Mitchell came to Southampton in 1917, to work for Supermarine, Mitchell designed 24 aircraft, including the Spitfire. Forever associated with the Battle of Britain, the legendary aircraft first flew from Southampton, in 1936.

Reginald J.Mitchell was born in Staffordshire, in 1895. After school he was apprenticed at a locomotive works and attended night classes at technical college. When he joined Supermarine he began designing seaplanes. By 1922 they were breaking speed records. In 1931 Mitchells’ Supermarine S6B, won the coveted Schneider Trophy. In 1934 the Air Ministry announced that it was looking for a new fighter plane. Mitchell, whose company was now part of Vickers Aviation, decided to meet the requirements of the Royal Air Force by adapting his Supermarine seaplane, including the 1,030 hp Rolls Royce Merlin II engine. The first Spitfire prototype appeared on 5th March, 1936. With its “slender aerodynamic lines and elliptical-plan wings”, it was praised as the smallest and cleanest aircraft that could be constructed around a man and an engine. It went into production in June 1937, the same month in which its creator died of cancer. Reginal Mitchell was the subject of the feature film First of the Few (1942).

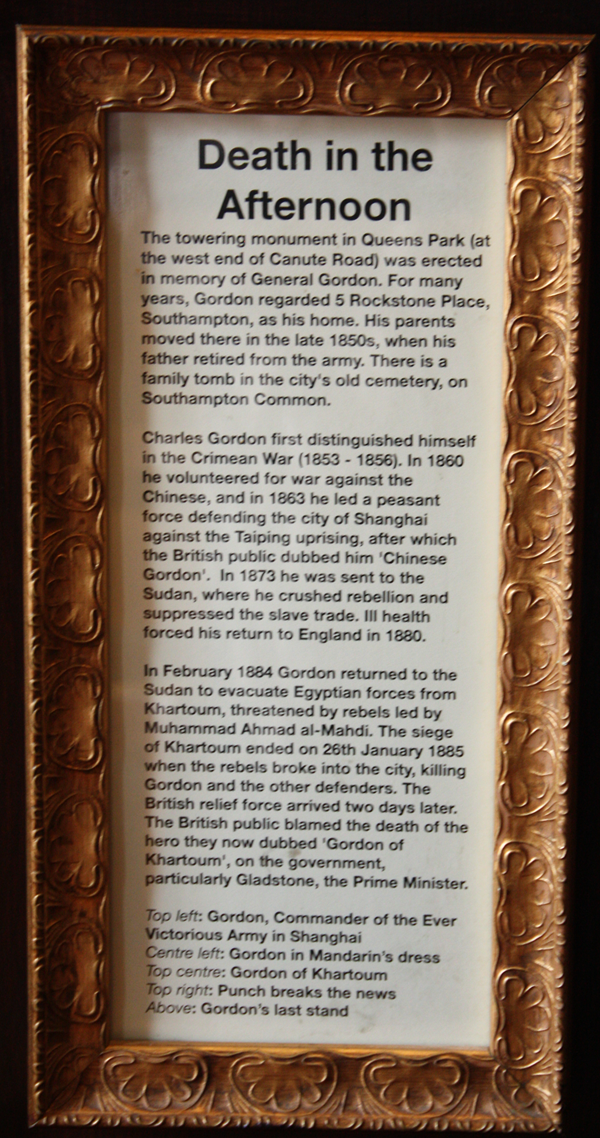

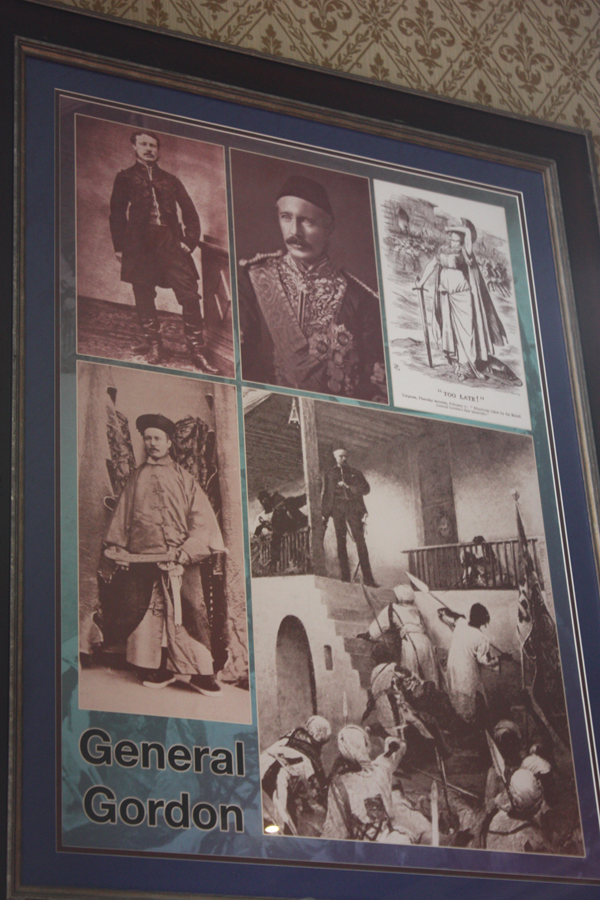

A framed passage about Charles Gordon.

The text reads:The towering monument in Queens Park (at the west end of Canute Road) was erected in memory of General Gordon. For many years, Gordon regarded 5 Rockstone Place, Southampton, as his home. His parents moved there in the late 1850s, when his father retired from the army. There is a family tomb in the city’s old cemetery, on Southampton Common.

Charles Gordon first distinguished himself in the Crimean War (1853 – 1856). In 1860 he volunteered for war against the Chinese, and in 1863 he led a peasant force defending the city of Shanghai against the Taiping uprising, after which the British public dubbed him ‘Chinese Gordon’. In 1873 he was sent to the Sudan, where he crushed rebellion and suppressed the slave trade. Ill health forced his return to England in 1880.

In February 1884 Gordon returned to the Sudan to evacuate Egyptian forces from Khartoum, threated by rebels led by Muhammad Admad al-Mahdi. The siege of Khartoum ended on 26th January 1885 when the rebels broke into the city, killing Gordon and the other defenders. The British relief force arrived two days later. The British public blamed the death of the hero they now dubbed ‘Gordon of Khartoum’, on the government, particularly Gladstone, the Prime Minister.

Top left: Gordon, Commander of the Ever Victorious Army in Shanghai

Centre left: Gordon in Mandarin’s dress

Top centre: Gordon of Khartoum

Top right: Punch breaks the news

Above: Gordon’s last stand.

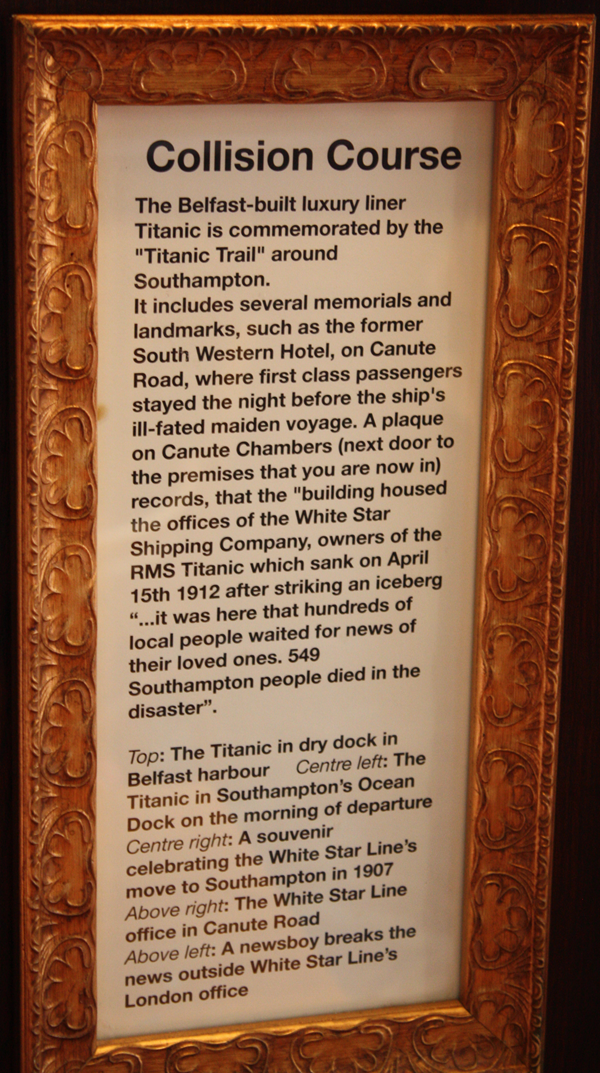

A framed passage about the Titanic.

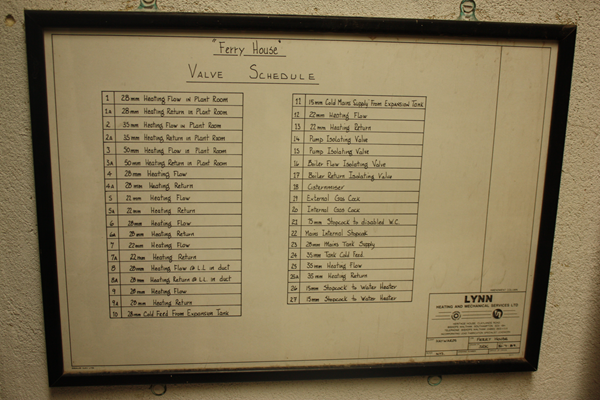

An original heating appliance, that remains untouched. Next to it on the wall is a valve schedule which dates back to 31st July 1989.

A replica of a ship’s figurehead, found on the end of the bar.

An acrylic, oil pastel painting entitled Impression Wave II, by Jason Adamson. Commissioned by J D Wetherspoon for the Sir Lucius Curtis, 2008.

The text reads: Jason Adamson was born in Belfast, like the Titanic, and, in the wake of that unfortunate ship, moved to Southampton when he was 5. Unlike the Titanic, he has never left, and studied for his degree at the University of Southampton, graduating in 2007.

Jason’s approach to art demands that images please, and interest, the eye, before they impart information of another kind – like a concept or a belief. Art should look like it takes skill to produce, and it should speak, by the use of colour and texture, to the feelings first and foremost.

An acrylic, oil pastel painting entitled The Race, by Jason Adamson. Commissioned by J D Wetherspoon for the Sir Lucius Curtis, 2008.

Next to the Sir Admiral Lucius Curtis is the Canute Chambers.

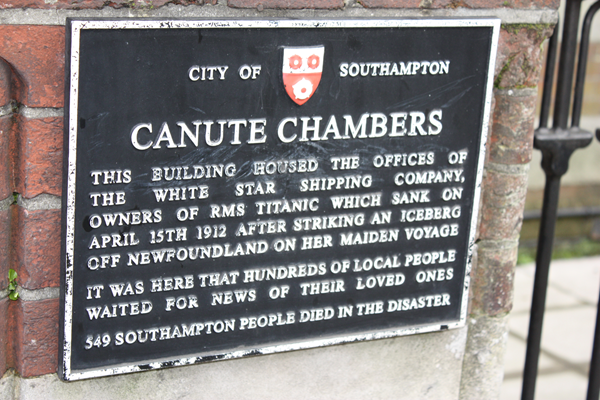

A plaque documenting the use of the Canute Chambers during the Titanic disaster.

The plaque reads: This building housed the offices of The White Star Shipping Company, owners of RMS Titanic which sank on April 15th 1912 after striking an iceberg off Newfoundland on her maiden voyage. It was here that hundreds of local people waited for news of their loved ones. 549 Southampton people died in the disaster.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk