The use of this site as a prison is thought to date from 1228. In 1805, accommodation at the gaol was improved by the building of a new prison for debtors. The very centre of this new building was the Governor’s House – now this pub. After a new prison opened in Romsey Road, in 1849, the old gaol closed and was sold.

A print and text about William Walker.

The text reads: Deep sea diver William Walker earned his place in history by literally plunging to the rescue when Winchester Cathedral began to list.

Known affectionately as ‘Diver Bill’, he worked closely with architect TG Jackson and engineer Francis Fox to secure its foundations, between 1905 and 1912.

During those seven years, he worked in total darkness to stabilise the faltering structure. Workmen lowered sacks of concrete to Diver Bill, who arranged them like bricks to underpin the walls.

Although, he handled around 25,800 bags of concrete, 114,900 concrete blocks and 900,000 bricks. He fought off possible infection from working in what was really a graveyard with the disinfectant powers of his pipe, which he always lit when he surfaced.

Meanwhile, about 500 tons of grouting were forced into cracks in the walls, and buttresses were added on the south side of the building.

The work cost around £113,000 in Edwardian times – the equivalent of well over one million pounds today. When it was finished, both King George V and the Archbishop of Canterbury congratulated Bill at a special thanksgiving service on 15 July 1912. Jackson and Fox were knighted, while Bill was made a member of the Victorian Order.

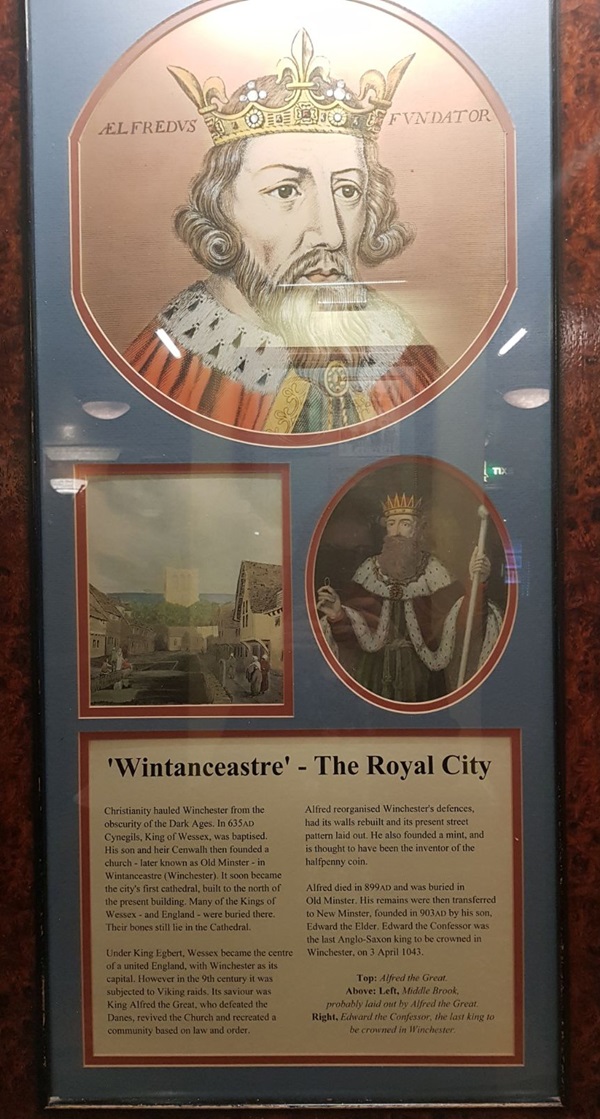

Illustrations and text about ‘Wintanceastre’ – the royal city.

The text reads: Christianity hauled Winchester from the obscurity of the Dark Ages. In 635AD Cynegils, King of Wessex, was baptised. His son and heir Cenwalh then founded a church - later known as Old Minster – in Wintanceastre (Winchester). It soon became the city’s first cathedral, built to the north of the present building. Many of the Kings of Wessex – and England – were buried there. Their bones still lie in the cathedral.

Under King Egbert, Wessex became the centre of a united England, with Winchester as its capital. However in the 9th century it was subjected to Viking raids. Its saviour was King Alfred the Great, who defeated the Danes, revived the Church and recreated a community based on law and order.

Alfred reorganised Winchester’s defences, had its walls rebuilt and its present street pattern laid out. He also founded a mint, and is thought to have been the inventor of the halfpenny coin.

Alfred died in 899AD and was buried in Old Minster. His remains were then transferred to New Minster, founded in 903AD by his son, Edward the Elder. Edward the Confessor was the last Anglo-Saxon king to be crowned in Winchester, on 3 April 1043.

Top: Alfred the Great

Above: left, Middle Brook, probably laid out by Alfred the Great, right, Edward the Confessor, the last king to be crowned in Winchester.

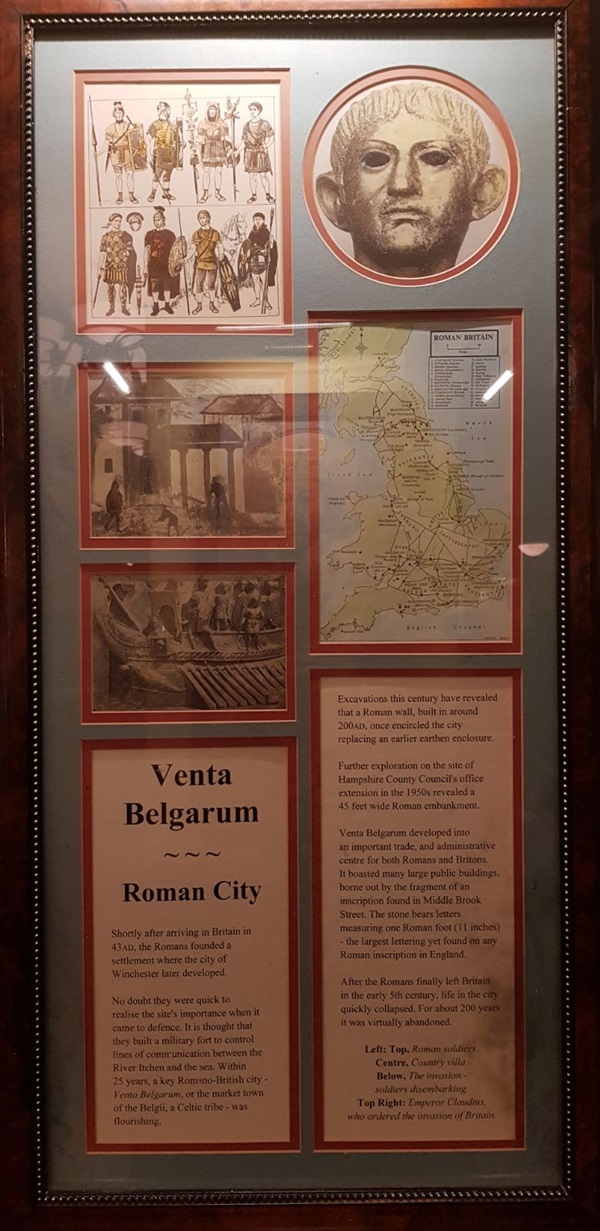

Illustrations and text about the Romans in Winchester.

The text reads: Shortly after arriving in Britain in 43AD, the Romans founded a settlement where the city of Winchester later developed.

No doubt they were quick to realise the site’s importance when it came to defence. It is thought that they built a military fort to control lines of communication between the River Itchen and the sea. Within 25 years, a key Romano-British city – Venta Belgarum, or the market town of the Belgii, a Celtic tribe – was flourishing.

Further exploration on the site of Hampshire County Council’s office extension in the 1950s revealed a 45 feet wide Roman embankment.

Venta Belgarum developed into an important trade and administrative centre for both Romans and Britons. It boasted many large public buildings, borne out by the fragment of an inscription found in Middle Brook Street. The stone bears letters measuring one Roman foot (11 inches) – the largest lettering yet found on any Roman inscription in England.

After the Romans finally left Britain in the early 5th century, life in the city quickly collapsed. For about 200 years it was virtually abandoned.

Left: top, Roman soldiers, centre, country villa, below, the invasion – soldiers disembarking

Top right: Emperor Claudius, who ordered the invasion of Britain.

An illustration and text about Charles Peace.

The text reads: Charles Peace became a fugitive from justice when he shot his next door neighbour. He had been ‘having relations’ with his neighbour’s wife at the time. Peace became known as the Banner Cross Murderer as a result, after the terrace where he lived in Sheffield.

Charles stained his face, dyed his hair black, and took to wearing glasses. He lived with Susan Grey, “a dreadful woman for drink and snuff”, in a house in south east London. They called themselves Mr and Mrs Thompson, were regular church-goers, and held musical evenings, where Charles would show off his skill on the violin, and recite poetry. Charles’s legal wife was kept out of sight in the basement.

By night Charles went out in his pony and trap, with his violin case full of tools, and burgled houses.

The Banner Cross Murderer, come south London housebreaker, alias respectable Mr Thompson, finally got his comeuppance when PC Robinson caught him breaking and entering in Blackheath.

The walnut stain and spectacles disguise was penetrated, and Charles was tried for murder.

In transit by train he made a final failed bid for freedom, via the window. His last words were directed at his last meal. After treating his warders to a little sermon on how a good Christian faces death, he looked at his plate and announced “this is bloody rotten bacon”.

A print and text about Mary Tudor’s wedding.

The text reads: Mary Tudor chose Winchester Cathedral for her wedding to Prince Philip of Spain. Daughter of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, she and Philip exchanged vows on 25 July, 1554.

Winchester was chosen for various reasons. By far the most important was the security risk, thanks to England’s fragile relationship with Spain. Geography was also a key consideration. Philip travelled by sea and docked at Southampton, so the city was conveniently nearby.

The Spanish Prince was escorted by an impressive armada. Mary was accompanied on the last stage of her journey by 3,000 horsemen and 300 bowmen.

They met for the first time at Wolvesey Palace, where Mary was guest of Bishop Gardiner.

The wedding date was chosen to coincide with St James’s Day, celebrating the patron saint of Spain. The cathedral was decorated with 12 Flanders tapestries, each about 30 feet long, telling the story of the Conquest of Tunis by Philip’s father. Later transported to Spain, they remain in Barcelona, Madrid and Seville.

Religious persecution during Mary’s reign led to her nickname ‘Bloody Mary’. During the last three years of her life, some 300 people were burned at the stake.

Above: Mary Tudor and Philip II of Spain.

An illustration and text about Winchester Cathedral.

The text reads: Just four years after his successful invasion, in 1066, William the Conqueror appointed Walkelin as the first of the Norman bishops. He then ordered his fellow countryman to build a new cathedral, which was probably the largest Romanesque church in Europe.

Work began in 1079. The King allowed Walkelin to get wood for the foundations and roof beams from Hampage Wood, telling him he could have as much as he could collect in three days.

William was both surprised and angry to discover that his cousin had stripped the area, leaving only one tree standing!

However, William was pleased with the end result, completed in 1093. At the time, it was the longest church in the world, extending 40 feet further west than it does today. To this day, only one European church is longer – St Peter’s in Rome.

Since then, much of the cathedral has been altered, but the crypt and transepts still give a good idea of the original building. The east arm was extended (1200-40), and the nave was remodelled in the 14th century.

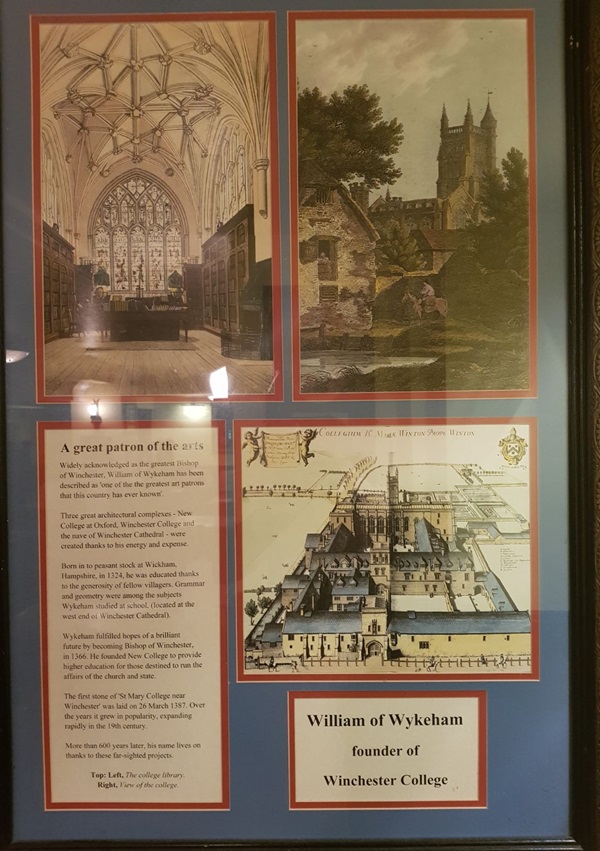

An illustration and text about William of Wykeham - founder of Winchester College.

The text reads: Widely acknowledged as the greatest Bishop of Winchester, William of Wykeham has been described as ‘one of the greatest art patrons that this country has ever known’.

Three great architectural complexes – New College at Oxford, Winchester College and the nave of Winchester Cathedral – were created thanks to his energy and expense.

Born in to peasant stock at Wickham, Hampshire, in 1324, he was educated thanks to the generosity of fellow villagers. Grammar and geometry were among the subjects Wykeham studied at school, (located at the west end of Winchester Cathedral).

Wykeham fulfilled hopes of a brilliant future by becoming Bishop of Winchester, in 1366. He founded New College to provide higher education for those destined to run the affairs of the church and state.

The first stone of St Mary College near Winchester was laid on 26 March, 1387. Over the years it grew in popularity, expanding rapidly in the 19th century.

More than 600 years later, his name lives on thanks to these far-sighted projects.

Top: left, the college library, right, view of the college.

A piece of Gaol House rock, followed by text.

The text reads: The significance of the incised stone set into this pillar is not known, but the year in question was of extreme significance both to the country and to Winchester.

King Charles II had chosen Winchester to be his residence when he was not required to be in London. He acquired the site of the former royal castle, and Sir Christopher Wren was appointed architect. Following the King’s lead, the nobility rushed to build town houses in Winchester, as did the church. This sudden explosion of courtly culture in Winchester came to a sudden end in 1685, when the King died.

Charles’ brother James had barely succeeded when one of the dead Kings’ illegitimate sons, James Crofts, Duke of Monmouth, attempted to take the throne by force. He landed at Lyme in Dorset with a small army, but with the promise of widespread support in the west. Taunton was the hotbed, but Winchester had its rebellious faction, mainly old Republicans from the Civil War. But Monmouth failed in an attempt to take Bristol, and was then defeated at Sedgemoor.

There followed the Bloody Assizes, presided over by Judge Jeffreys. Only one execution took place in Winchester, but it was notably ruthless. Alice Lisle, known as Lady Lisle, was the widow of the famous regicide (a signatory to the death warrant of King Charles I) John Lisle, and 70 years old. Judge Jeffreys bullied the jury into a guilty verdict, sending them back three times when they voted for an acquittal. The King refused a pardon, but changed her sentence from burning to beheading.

James II, like his late brother, was Catholic by nature, a leaning unpopular with his people. Charles had kept his faith private. James pursued it openly. However, he also asserted religious tolerance, and supported the established Church of England.

In Catholic France in 1685, the Edict of Nantes, which tolerated Huguenot Protestants, was revoked. Cruel persecutions followed and large numbers fled to England. James welcomed and protected them. There was a great influx of Protestant ‘asylum seekers’ into Winchester and the King supported them from his own purse, and began general subscriptions for their relief. He also rushed through citizenship for them at no expense.

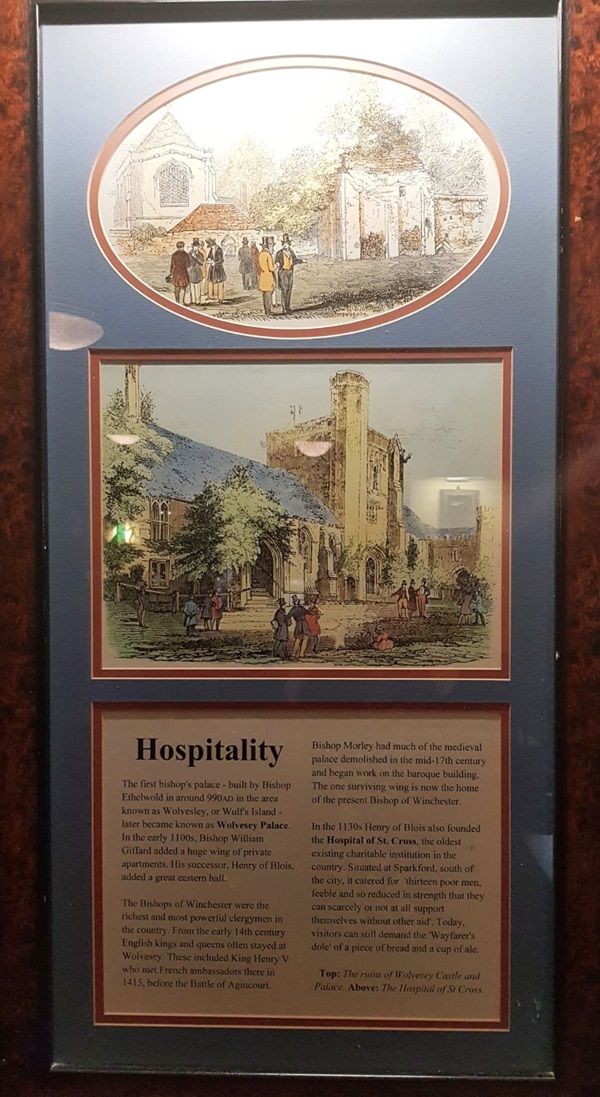

Illustrations and text about hospitality in Winchester.

The text reads: The first bishop’s palace – built by Bishop Ethelwold in around 990AD in the area known as Wolvesley, or Wulf’s Island – later became known as Wolvesey Palace. In the early 1100s, Bishop William Giffard added a huge wing of private apartments. His successor, Henry of Blois, added a great eastern hall.

The Bishops of Winchester were the richest and most powerful clergymen in the country. From the early 14th century English kings and queens often stayed at Wolvesey. These included King Henry V who met French ambassadors there in 1415, before the Battle of Agincourt.

Bishop Morely had much of the medieval palace demolished in the mid 17th century and began work on the baroque building. The one surviving wing is now the home of the present Bishop of Winchester.

In the 1130s Henry of Blois also founded the Hospital of St Cross, the oldest existing charitable institution in the country. Situated at Sparkford, south of the city, it catered for ‘thirteen poor men, feeble and so reduced in strength that they can scarcely or not at all support themselves without other aid’. Today, visitors can still demand the ‘Wayfarer’s dole’ of a piece of bread and a cup of ale.

Top: The ruins of Wolvesey Castle and Palace

Above: The Hospital of St Cross.

An illustration and text about William the Conqueror.

The text reads: After his victory at the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, William the Conqueror lost no time in making his mark on his new kingdom. In Winchester he orders that a castle be built on the highest ground within the city walls. Some sixty Saxon families lost their homes as the area was cleared.

William also extended the Anglo-Saxon royal palace, west of Old Minister. Building work took place on land exchanged with New Minister, whose monks were believed to have backed King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. However it was not used as a royal residence for long. From around 1100, the new castle became the main Winchester base for Norman and Plantagenet kings.

The annual fair on St Giles Hill began during the reign of William Rufus (1087-1100). It quickly became popular and by the mid 12th century had become one of the great international fairs of England. During the 16 days of the fair no other trading was allowed in the city, and the church received all profits and revenues from the event.

Another enduring reminder of Norman times is the priceless late 12th century Winchester Bible, kept in the Cathedral Library. The feature of the Bible which often arouses greatest interest is the splendid series of initials, showing the skill of the Winchester artists of that time.

Above: King William I.

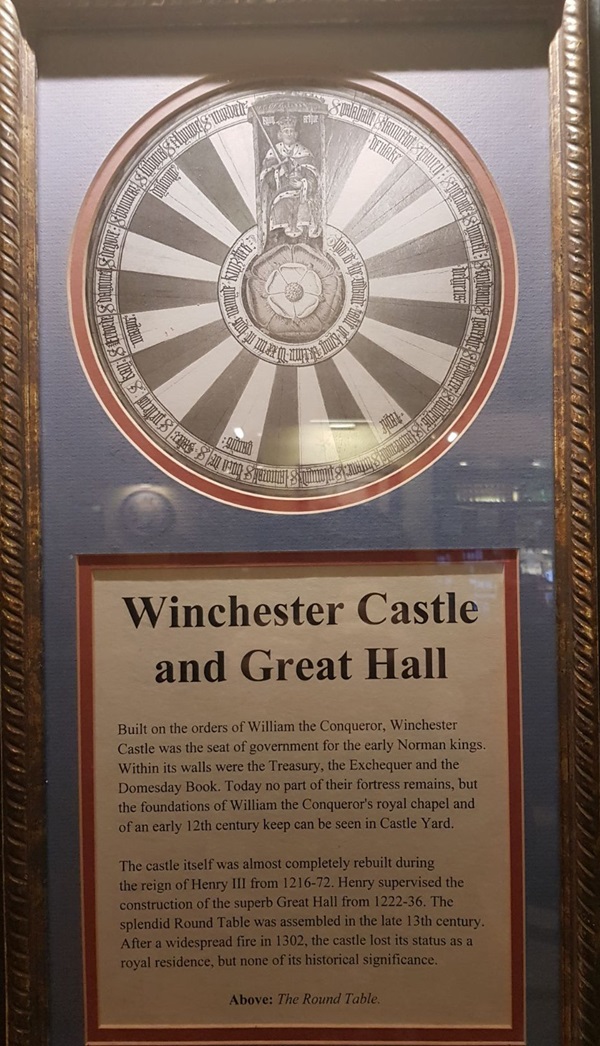

An illustration and text about Winchester Castle and Great Hall.

The text reads: Built on the orders of William the Conqueror, Winchester Castle was the seat of government for the early Norman kings. Within its walls were the treasury, the exchequer and the Domesday Book. Today no part of their fortress remains, but the foundations of William the Conqueror’s royal chapel and of an early 12th century keep can be seen in Castle Yard.

The castle itself was almost completely rebuilt during the reign of Henry III from 1216-72. Henry supervised the construction of the superb Great Hall from 1222-36. The splendid Round Table was assembled in the late 13th century. After a widespread fire in 1302, the castle lost its status as a royal residence, but none of its historical significance.

Above: The Round Table.

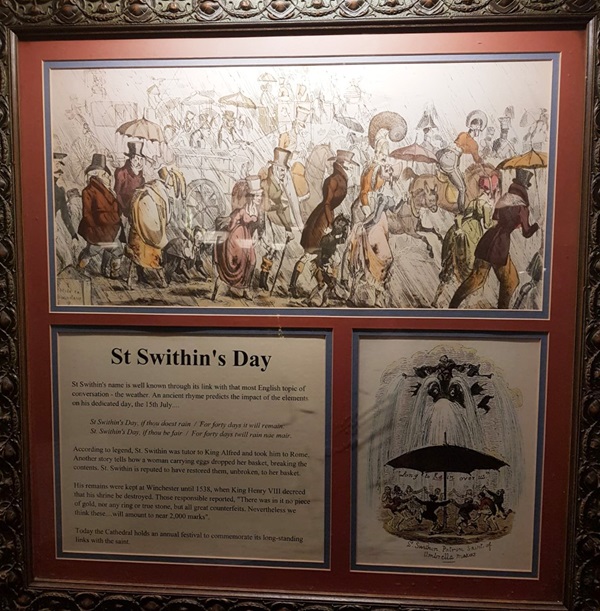

Illustrations and text about St Swithin’s Day.

The text reads: St Swithin’s name is well known through its link with that most English topic of conversation – the weather. An ancient rhyme predicts the impact of the elements on his dedicated day, the 15 July…

St Swithin’s Day, if thou doest rain / For forty days it will remain:

St Swithin’s Day, if thou be fair / For forty days twill rain nae mair.

According to legend, St Swithin was tutor to King Alfred and took him to Rome. Another story tells how a woman carrying eggs dropped her basket, breaking the contents. St Swithin is reputed to have restored them, unbroken, to her basket.

His remains were kept at Winchester until 1538, when King Henry VIII decreed that his shrine be destroyed. Those responsible reported, “There was in it no piece of gold, nor any ring or true stone, but all great counterfeits. Nevertheless we think these… will amount to near 2,000 marks”.

Today the cathedral holds an annual festival to commemorate its long standing links with the saint.

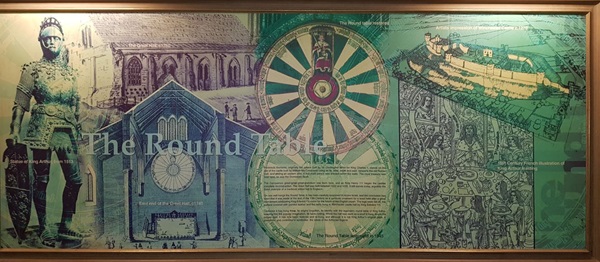

Illustrations and text about the Round Table.

The text reads: Peninsula Barracks, originally the palace built by Sir Christopher Wren for King Charles I, stands on the site of the castle built by William the Conqueror, using as its west, south and east ramparts the old Roman wall, and adding an eastern side. A first royal palace was erected within the walls. The royal treasury was kept here, as was the Domesday Book.

The Conquerors great-great-great-grandson was born here, and as King Henry III began the castles complete reconstruction. The Great Hall was built between 1222 and 1235. It still stands today, arguably the finest example of a medieval aisled hall in England.

On one wall hangs the Round Table. It has been carefully examined in recent times, and the conclusion has been that it was made at the end of the 13th century as a symbolic ornament for a feast held after a great tournament celebrating King Edward I’s vision for the future of the English crown. The legs were cut off, the surface covered with painted leather and the table hung in Winchester castle hall by King Edward III.

Centuries it has hung there, its origins forgotten, its identity with the legendary round table of King Arthur seeping into the popular imagination, its fabric rotting. Whilst the hall was used as a court it hung above the judge’s seat. It has now been restored and re-hung, and although it is not King Arthur’s original table, it preserves, and continues to symbolise, the ideals of the Arthurian legend.

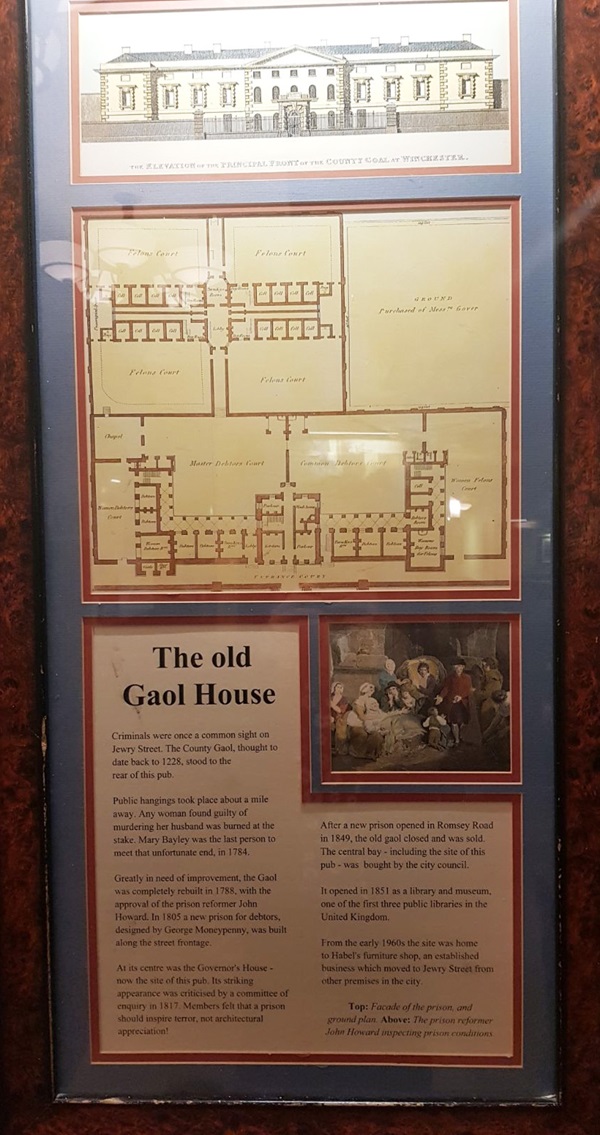

An illustration and text about the old Gaol House.

The text reads: Criminals were once a common sight on Jewry Street. The County Gaol, thought to date back to 1228, stood to the rear of this pub.

Public hangings took place about a mile away. Any woman found guilty of murdering her husband was burned at the stake. Mary Bayley was the last person to meet that unfortunate end, in 1784.

Greatly in need of improvement, the Gaol was completely rebuilt in 1788, with the approval of the prison reformer John Howard. In 1805 a new prison for debtors, designed by George Moneypenny, was built along the street frontage.

At its centre was the Governor’s House – now the site of this pub. Its striking appearance was criticised by a committee of enquiry in 1817. Members felt that a prison should inspire terror, not architectural appreciation!

After a new prison opened in Romsey Road in 1849, the Old Gaol closed and was sold. The central bay – including the site of this pub – was bought by the city council.

It opened in 1851 as a library and museum, one of the first three public libraries in the United Kingdom.

From the early 1960s the site was home to Habel’s furniture shop, an established business which moved to Jewry Street from other premises in the city.

Top: Façade of the prison, and ground plan

Above: The prison reformer John Howard inspecting prison conditions.

An illustration and text about Jane Austen.

The text reads: Famed for her sharp wit and literary skill, Jane Austen spent the last two months of her life in Winchester, and lies buried in the cathedral.

Born in 1775 in Steventon, Hampshire, where her father was rector, she later lived in Bath, Southampton and Chawton before coming to Winchester.

By the time of her death, aged just 41, she had written six novels that are still widely read today. Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park and Emma were all published during her lifetime. Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, her last work, both appeared after her death in 1817.

She came to Winchester for the sake of her health. Under the care of Winchester doctor Giles King Lyford, she took rooms in College Street. She spent most of her time in a “neat little drawing room with a bow window”.

Jane Austin was buried in Winchester Cathedral on 24 July 1817. Her gravestone in the north aisle pays tribute to the ‘benevolence of her heart, the sweetness of her temper and the extraordinary endowment of her mind’.

Artwork and sculptures, inspired by this former prison, can be found around the pub.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

Extract from Wetherspoon News Summer 2018.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk