The ‘moon’ part of this Wetherspoon free house’s name links it with the ideal pub described by George Orwell. The famous writer called his fictitious pub ‘Moon Under Water’. The ‘cross’ refers to the nearby monument, erected in 1290 by King Edward I in honour of his queen – Eleanor of Castille. It is one of 12 crosses which mark the overnight stopping places of the queen’s funeral cortège, on its way to Westminster Abbey.

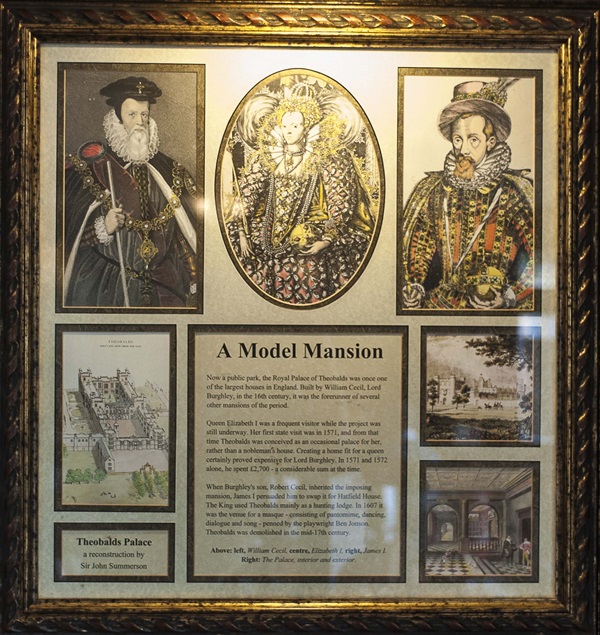

Prints, illustrations and text about the Royal palace of Theobalds.

The text reads: Now a public park, the Royal Palace of Theobalds was once one of the largest houses in England. Built by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, in the 16th century, it was the forerunner of several other mansions of the period.

Queen Elizabeth I was a frequent visitor while the project was still underway. Her first state visit was in 1571, and from that time Theobalds was conceived as an occasional palace for her, rather than a nobleman’s house. Creating a home fit for a queen certainly proved expensive for Lord Burghley. In 1571 and 1572 alone, he spent £2,700 – a considerable sum at the time.

When Burghley’s son, Robert Cecil, inherited the imposing mansion, James I persuaded him to swap it for Hatfield House. The King used Theobalds mainly as a hunting lodge. In 1607 it was the venue for a masque – consisting of pantomime, dancing, dialogue and song – penned by the playwright Ben Jonson. Theobalds was demolished in the mid 17th century.

Above: left, William Cecil, centre, Elizabeth I, right, James I

Right: The palace, interior and exterior.

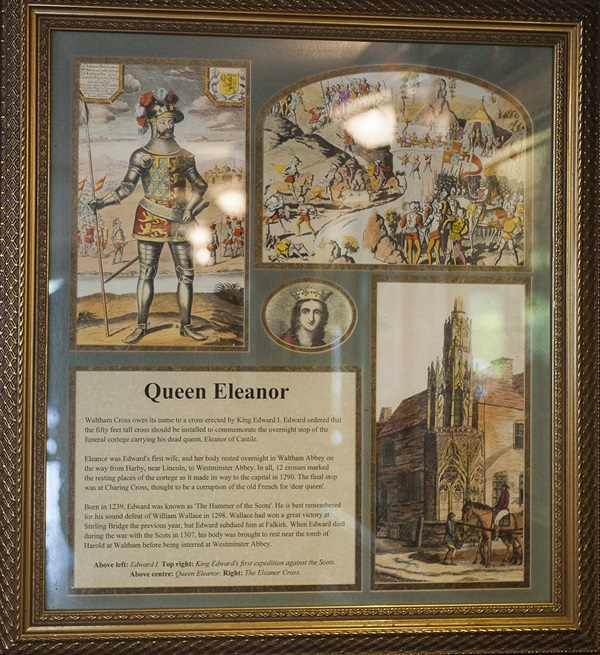

Illustrations and text about Queen Eleanor.

The text reads: Waltham Cross owes its name to a cross erected by King Edward I. Edward ordered that the fifty feet tall cross should be installed to commemorate the overnight stop of the funeral cortege carrying his dead queen, Eleanor of Castile.

Eleanor was Edward’s first wife, and her body rested overnight in Waltham Abbey on the way from Harby, near Lincoln, to Westminster Abbey. In all, 12 crosses marked the resting places of the cortege as it made its way to the capital in 1290. The final stop was at Charring Cross, thought to be a corruption of the old French for ‘dear queen’.

Born in 1239, Edward was known as ‘The Hammer of the Scots’. He is best remembered for his sound defeat of William Wallace in 1298. Wallace had won a great victory at Stirling Bridge the previous year. But Edward subdued him at Falkirk. When Edward died during the war with the Scots in 1307, his body was brought to rest near the tomb of Harold at Waltham before being interred at Westminster Abbey.

Above left: Edward I

Top right: King Edward’s first expedition against the Scots

Above centre: Queen Eleanor

Right: The Eleanor Cross.

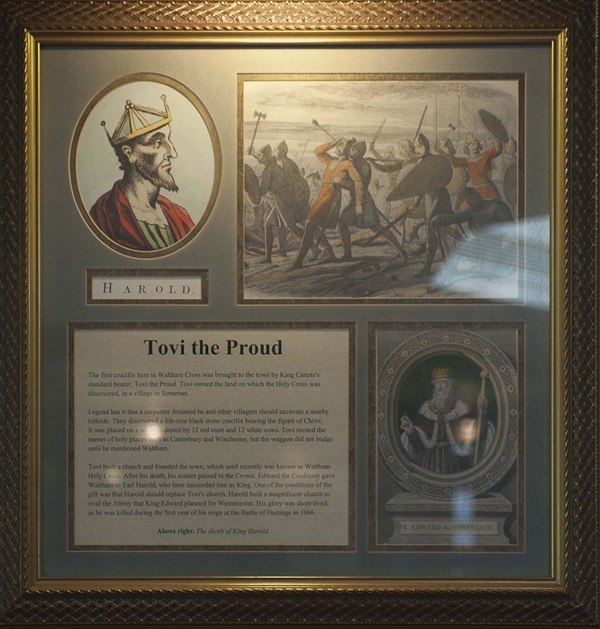

Illustrations and text about Tovi the Proud.

The text reads: The first crucifix here in Waltham Cross was brought to the town by King Canute’s standard bearer, Tovi the Proud. Tovi owned the land on which he Holy Cross was discovered, in a village in Somerset.

Legend has it that a carpenter dreamed he and other villagers should excavate a nearby hillside. They discovered a life-size black stone crucifix bearing the figure of Christ. It was placed on a wagon drawn by 12 red oxen and 12 white cows. Tovi recited the names of holy places such as Canterbury and Winchester, but the waggon did not budge until he mentioned Waltham.

Tovi built a church and founded the town, which until recently was known as Waltham Holy Cross. After his death, his estates passed to the Crown. Edward the Confessor gave Waltham to Earl Harold, who later succeeded him as King. One of the conditions of the gift was that Harold should replace Tovi’s church. Harold built a magnificent church to rival the abbey that King Edward planned for Westminster. His glory was short-lived, as he was killed during the first year of his reign at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Above right: The death of King Harold.

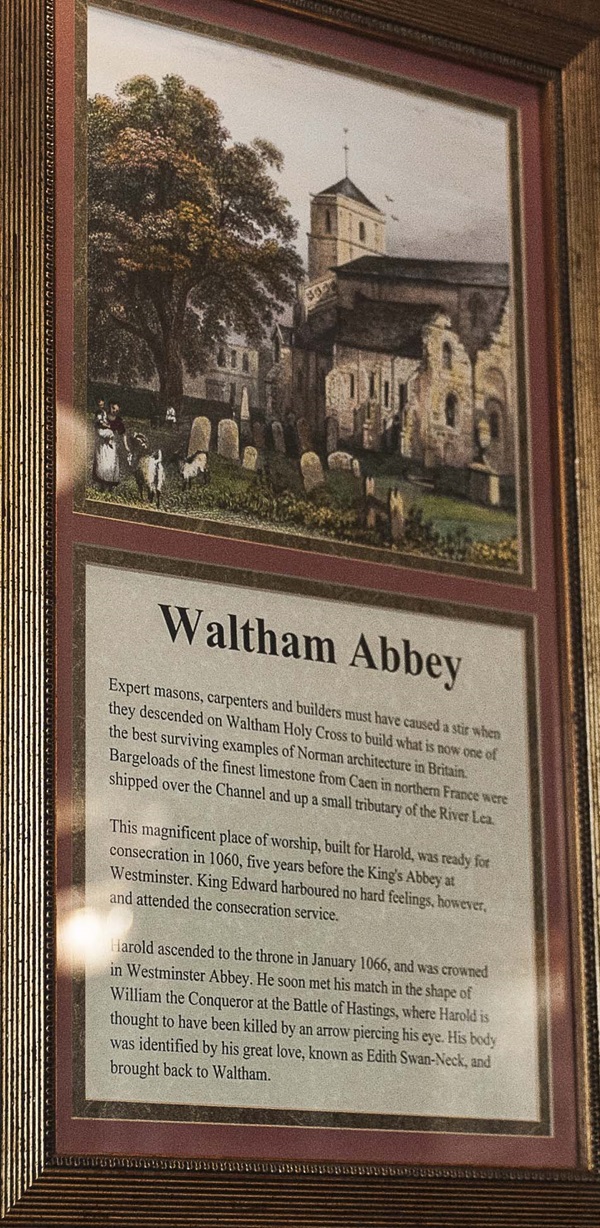

A print and text about Waltham Abbey.

The text reads: Expert masons, carpenters and builders must have caused a stir when they descended on Waltham Holy Cross to build what is now one of the best surviving examples of northern architecture in Britain. Barge loads of the finest limestone from Caen in northern France were shipped over the Channel and up a small tributary of the River Lea.

This magnificent place of worship, built for Harold, was ready for consecration in 1060, five years before the King’s Abbey at Westminster. King Edward harboured no hard feelings, however, and attended the consecration service.

Harold ascended to the throne in January 1066, and was crowned in Westminster Abbey. He soon met his match in shape of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings, where Harold is thought to have been killed by an arrow piercing his eye. His body was identified by his great love, known as Edith Swan-Neck, and brought back to Waltham.

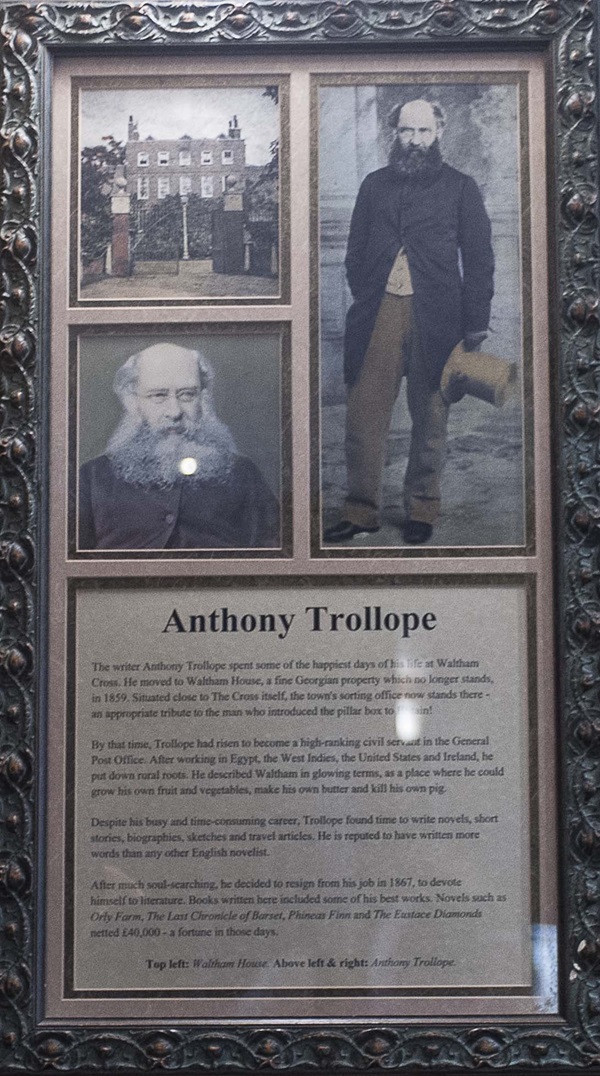

Prints and text about Anthony Trollope.

The text reads: The writer Anthony Trollope spent some of the happiest days of his life at Waltham Cross. He moved to Waltham House, a fine Georgian property which no longer stands, in 1859. Situated close to the cross itself, the town’s sorting office now stands there as an appropriate tribute to the man who introduced the pillar box to Britain!

By the time, Trollope had risen to become a high-ranking civil servant in the general post office. After working in Egypt, the West Indies, the United States and Ireland, he put down rural roots. He described Waltham in glowing terms, as a place where he could grow his own fruit and vegetables, make his own butter and kill his own pig.

Despite his busy and time-consuming career, Trollope found time to write novels, short stories, biographies, sketches and travel articles. He is reputed to have written more words than any other English novelist.

After much soul-searching he decided to resign from his pub in 1867, to devote himself to literature. Books written here included some of his best works. Novels such as Orly Farm, The Last Chronicle of Barset, Phinean and The Eustace Diamonds netted £40,000 – a fortune in those days.

Top left: Waltham House

Above left & right: Anthony Trollope.

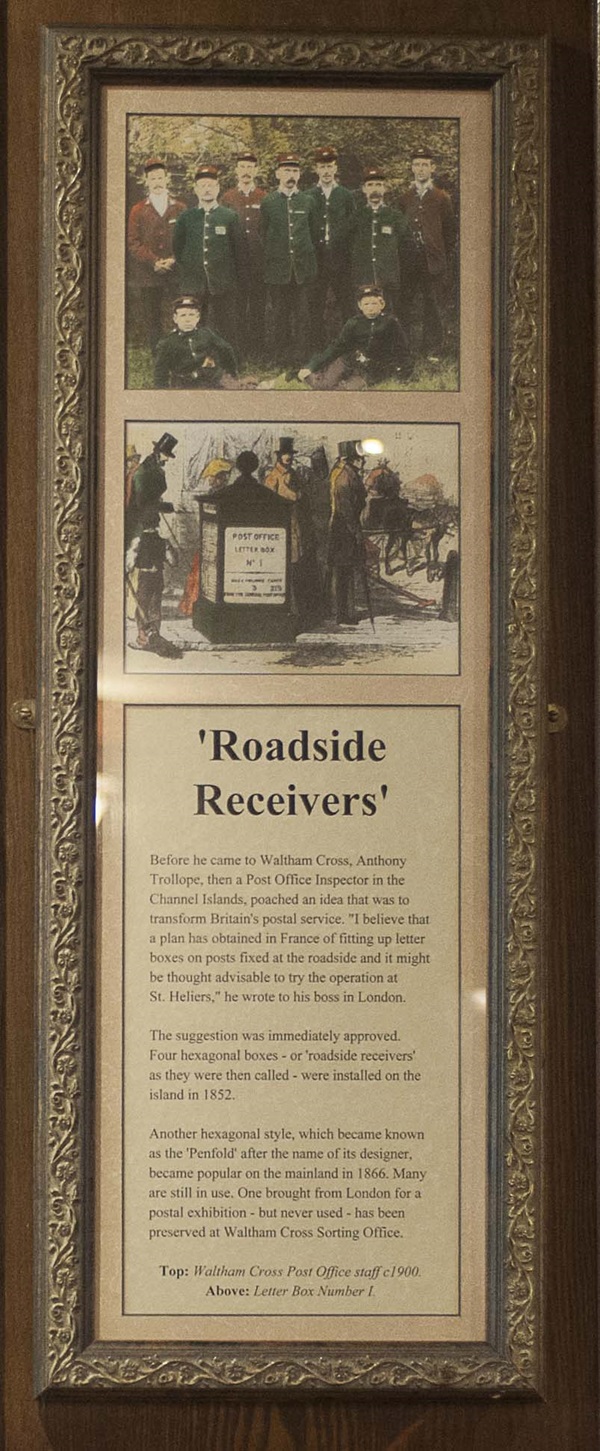

Prints and text about the ‘roadside receivers’.

The text reads: Before he came to Waltham Cross, Anthony Trollope, then post office inspector in the Channel Islands, poached an idea that was to transform Britain’s postal service. “I believe that a plan has obtained in France of fitting up letter boxes on post fixed at the roadside and it might be thought advisable to try the operation at St. Heliers.” He wrote to his boss in London.

The suggestion was immediately approved. Four hexagonal boxes – or ‘roadside receivers’ as they were then called – were installed on the island in1852.

Another hexagonal style, which became known as the ‘Penfold’ after the name of its designer, became popular on the mainland in 1866. Many are still in use. One brought from London for a postal exhibition – but never used – has been preserved at Waltham Cross Sorting Office.

Top: Waltham Cross Post Office staff c1900

Above: Letter Box Number 1.

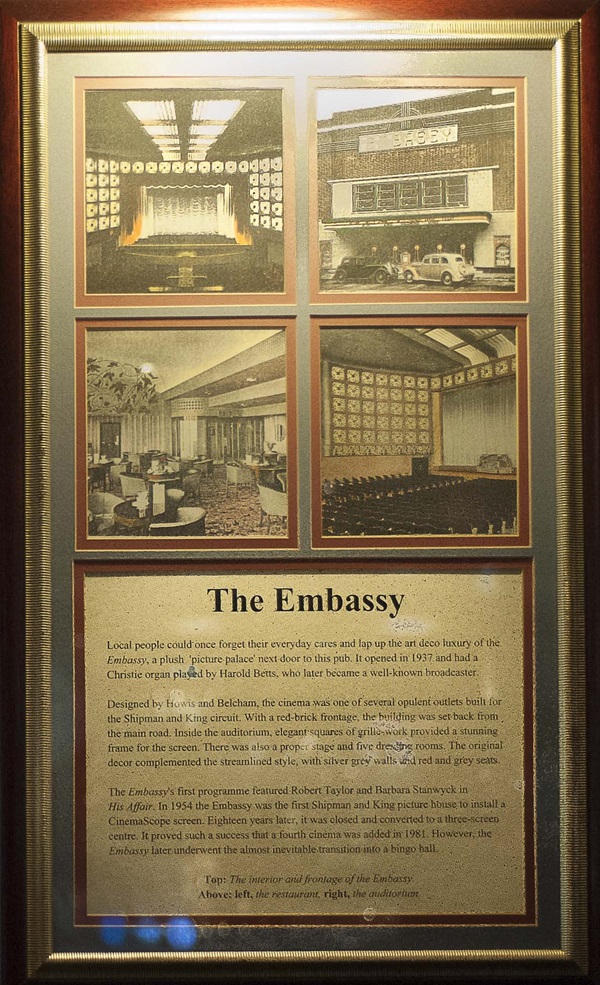

Prints and text about the Embassy.

The text reads: Local people could once forget their everyday cares and lap up the art deco luxury of the Embassy, a push ‘picture palace’ next door to this pub. It opened in 1937 and has a Christie organ played by Harold Betts, who later became a well-known broadcaster.

Designed by Howis and Belcham, the cinema was one of several opulent outlets built for the Shipman and King circuit. With a red-brick frontage, the building was set back from the main road. Inside the auditorium, elegant squares of grilled work provided a stunning frame for the screen. There was also a proper stage and five dressing rooms. The original décor complemented the streamline style, with silver grey walls and red and grey seats.

The Embassy’s first programme featured Robert Taylor and Barbra Stanwyck in His Affair. In 1954 the Embassy was the first Shipman and King picture house to install a CinemaScope screen. Eighteen years later, it was closed and converted to a three-screen centre. It proved such a success that a fourth cinema was added in 1981. However, the Embassy later underwent the almost inevitable transition into a bingo hall.

Top: The interior and frontage of the Embassy

Above: left, the restaurant

Right: The auditorium.

A painting entitled The Bird of Life, Creator and Destroyer of All, by Gabrielle Roberts-Dalton.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk