This was originally built as an opera house, opening in 1902 and becoming a cinema in 1931; nearly 40 years later, it made the transition into a bingo hall and then finally this pub.

Internal photographs of The Opera House.

The features include grand chandeliers and original booths and stalls.

This equipment is the original lighting control, dating back to when the building was an opera house.

The original signage above the entrances is still in place.

Photographs of the Opera House preparing for the opera.

Prints and illustrations relating to the Grand Opera.

Prints and illustrations referring the comic operas produced by Gilbert and Sullivan.

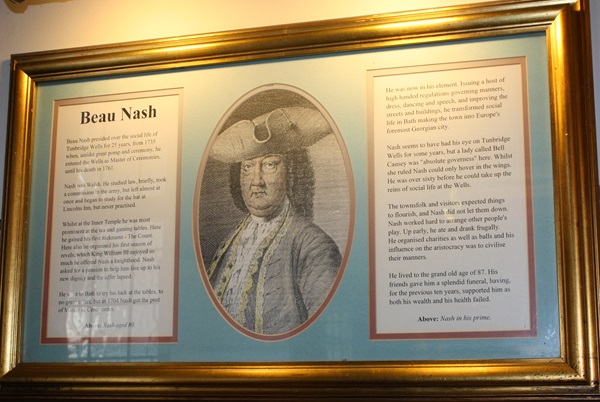

An illustration and text about Beau Nash.

The texts reads: Beau Nash presided over the social life of Tunbridge Wells for 25 years, from 1735 when, amidst great pomp and ceremony, he entered the Wells as Master of Ceremonies, until his death in 1761.

Nash was Welsh. He studied law, briefly, took a commission in the army, but left almost at once and began to study for the bar at Lincolns Inn, but never practised.

Whilst at the Inner Temple he was most prominent at the tea and gaming tables. Here he gained his first nickname – The Count. Here also he organised the first season of revels, which King William III enjoyed so much he offered Nash a knighthood. Nash asked for a pension to help him live up to his new dignity and the offer lapsed.

He went to Bath to try his luck at the tables, to no great effect, but in 1704 Nash got the post of Master of Ceremonies.

Above Nash aged 80.

He was now in his element. Issuing a host of high handed regulations governing manners, dress, dancing and speech, and improving the streets and buildings, he transformed social life in Bath making the town into Europe’s foremost Georgian city.

Nash seems to have had his eye on Tunbridge Wells for some years, but a lady called Bell Causey was “absolute governess” here. Whilst she ruled Nash could only hover in the wings. He was over sixty before he could take up the reins of social life at the Wells.

The townsfolk and visitors expected things to flourish, and Nash did not let them down. Nash worked hard to arrange other people’s play. Up early, he ate and drank frugally. He organised charities as well as balls and his influence on the aristocracy was to civilise their manners.

He lived to the grand old age of 87. His friends gave him a splendid funeral, having, for the previous ten years, supported him as both his wealth and health failed.

Above: Nash aged 80.

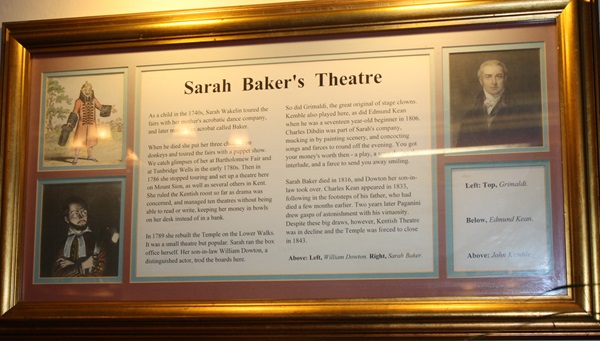

Prints and text about Sarah Baker’s Theatre.

The texts reads: As a child in the 1740s, Sarah Wakelin toured the fairs with her mother’s acrobatic dance company, and later married an acrobat called Baker.

When he died she put her three children on donkeys and toured the fairs with a puppet show. We catch glimpses of her at Bartholomew Fair and at Tunbridge Wells in the early 1780s. Then in 1786 she stopped touring and set up a theatre here on Mount Sion, as well as several others in Kent. She ruled the Kentish roost so far as drama being concerned, and managed ten theatres without being able to read or write, keeping her money in bowls on her desk instead of in a bank.

In 1789 she rebuilt the Temple on the Lower Walks. It was a small theatre but popular. Sarah ran the box office herself. Her son-in-law William Dowton, a distinguished actor, trod the boards here.

So did Grimaldi, the great original of stage clowns. Kemble also played here, as did Edmund Kean when he was a seventeen year-old beginner in 1806. Charles Dibdin was part of Sarah’s company mucking in by painting scenery and concocting songs and farces to round off the evening. You got your money’s worth then – a play, a song during the interlude, and a farce to send you away smiling.

Sarah Baker died in 1816, and Dowton her son-in-law took over. Charles Kean appeared in 1833, following in the footsteps of his father, who had died a few months earlier. Two years later Paganini drew gasps of astonishment with his virtuosity. Despite these big draws, however, Kentish Theatre was in decline and the Temple was forced to close in 1843.

Left: Top, Grimaldi

Below, Edmund Kean

Above: John Kemble.

A print and text about Mrs Montagu and the Blue Stocking Society.

The texts reads: Mrs Montagu came to the Wells regularly from 1733, when she was thirteen, until around 1780. Dr Johnson, a stern critic if ever there was one, praised her conversation. He described her as, “This most extraordinary woman”.

Mrs Montagu was a founder member of Blue Stocking Club, and London’s leading hostess. She was witty, well-read, and something of a hypochondriac. She was here sufficiently often to be addressed in a poem as 'The Naiad of Tunbridge Wells’

The Blue Stockings were ladies who tried to substitute literary conversation for card playing. These parties pioneered by Mrs Montagu, and her friends Mrs Vesey and Mrs Ord.

Dress at the intellectual soirees was more relaxed than was usual. One Benjamin Stillingfleet wore blue worsted stockings instead of black silks, and the regulars at these get-togethers were dubbed the ‘Blue Stocking Society’.

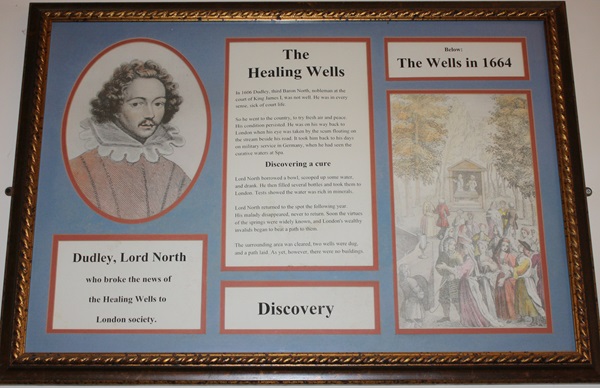

Prints and text about Dudley, third Baron North and the Healing Wells.

The texts reads: In 1606 Dudley, third Baron North, nobleman at the court of King James I, was not well. He was in every sense, sick of court life.

So he went to the country, to try fresh air and peace. His condition persisted. He was on his way back to London when his eye was taken by the scum floating on the stream behind his road. It took him back to his days on the military service in Germany, when he had seen the curative waters at Spa.

Discovering a cure

Lord North borrowed a bowl, scooped up some water, and drank. He then filled several bottles and took them to London. Tests showed the water was rich in minerals.

Lord North returned to the spot the following year. His malady disappeared, never to return. Soon the virtues of the springs were widely known, and London’s wealthy invalids began to beat a path to them.

The surrounding area was cleared, two wells were dug and a path laid. As yet, however, there were no buildings.

Left: Dudley, Lord North, who broke the news of the Healing Wells to London society

Right: The Wells in 1664.

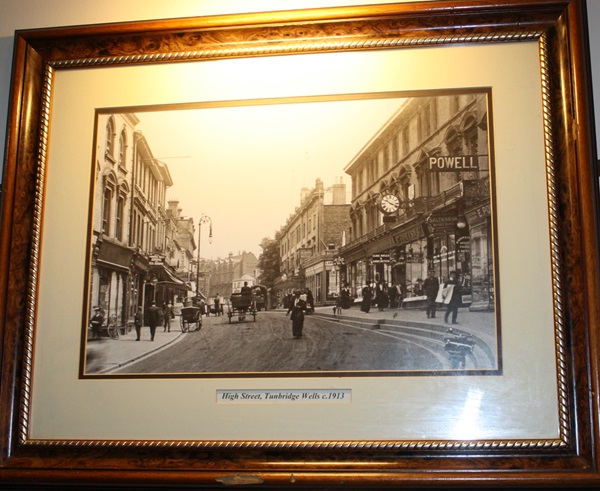

A photograph of High Street, Tunbridge Wells, c1913.

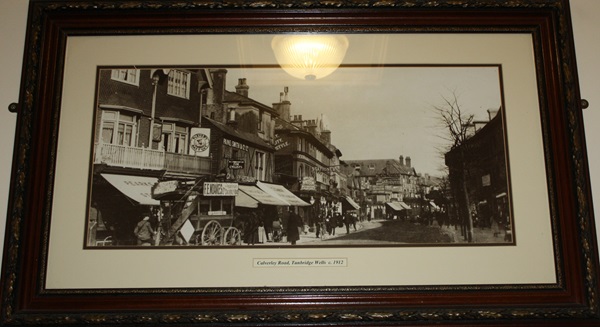

A photograph of Calverley Road, Tunbridge Wells, c1912.

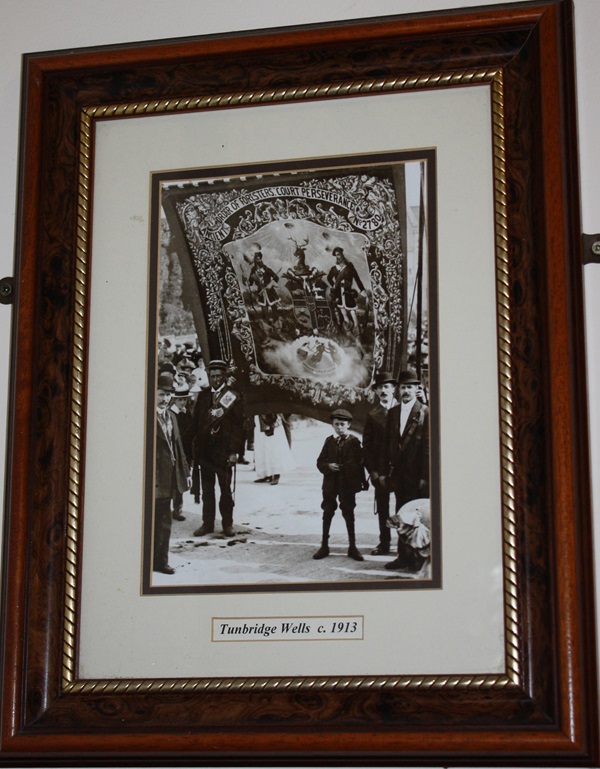

A photograph of Tunbridge Wells, c1913.

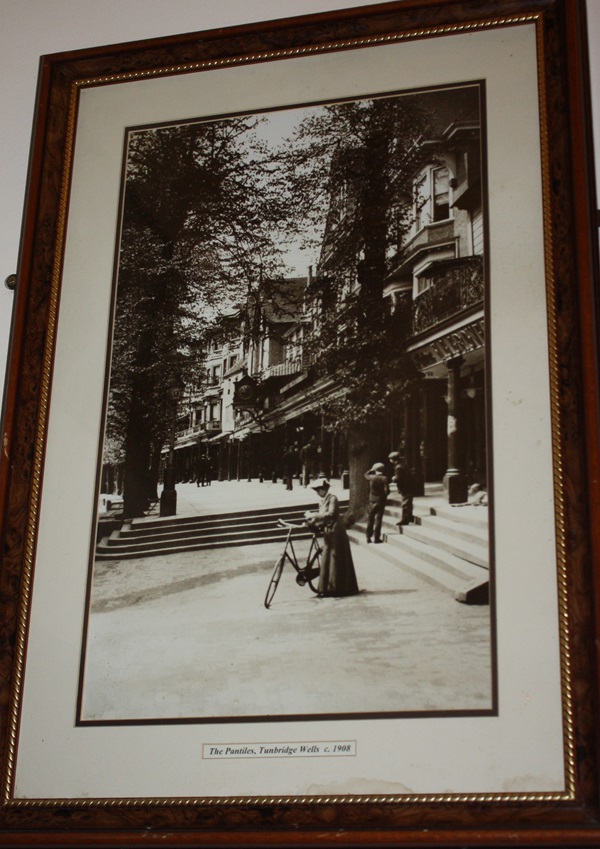

A photograph of The Pantiles, Tunbridge Wells, c1908.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

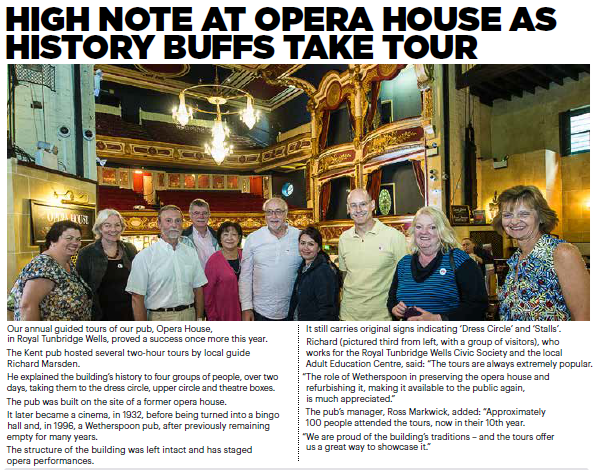

Extract from Wetherspoon News Autumn 2018.

Extract from Wetherspoon News Winter 2018.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk