This pub is named after the printer and publisher who introduced Gravesend’s first printing press, in 1786, and opened the town’s first library at the back of his high-street shop, where he published illustrated children’s books, including Reading Made Easy and, in 1797, The History of Gravesend and Milton – the first history book of Gravesend.

Text about The Robert Pocock.

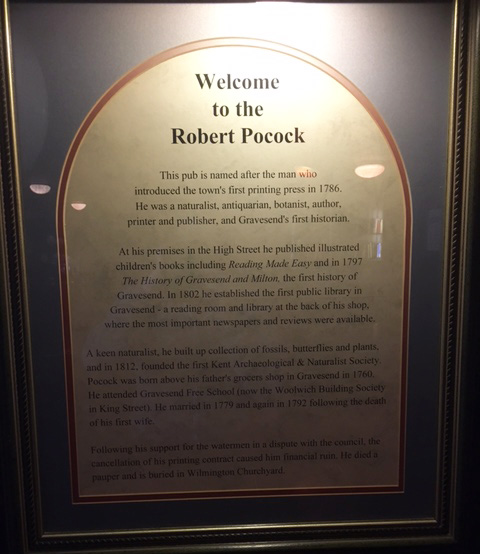

The text reads: This pub is named after the man who introduced the town’s first printing press in 1786. He was a naturalist, antiquarian, botanist, author, printer and publisher, and Gravesend’s first historian.

At his premises in High Street he published illustrated children’s books including Reading Made Easy and in 1797 The History of Gravesend and Milton, the first history of Gravesend. In 1802 he established the first public library in Gravesend – a reading room and library at the back of his shop, where the most important newspapers and reviews were available.

A keen naturalist, he built up a collection of fossils, butterflies and plants, and in 1812, founded the first Kent Archaeological and Naturalist Society. Pocock was born above his father’s shop in Gravesend in 1760. He attended Gravesend Free School (now the Woolwich Building Society in King Street). He married in 1779 and again in 1792 following the death of his first wife.

Following the support for the watermen in a dispute with the council, the cancellation of his printing contract caused him financial ruin. He died a pauper and his buried in Wilmington churchyard.

Illustrations inspired by Robert Pocock.

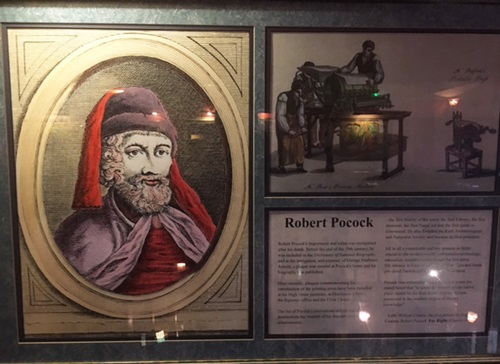

Illustrations and text about Robert Pocock.

The text reads: Robert Pocock’s importance and value was recognised after his death. Before the end of the 19th century, he was included in the Dictionary of National Biography, and at the instigation, and expense, of George Mathews Arnold, a plaque was erected at Pocock’s home and his biography was published.

More recently, plaques commemorating his introduction of the printing press have been installed at his High Street premises, at Gravesend Library, the Reporter office and the Civic Centre.

The list of Pocock’s innovations in Gravesend demonstrate the breadth of his interests and achievements: the first history of the town, the first library, the first museum, the first Naval list and the first guide to Gravesend. He also founded the Kent Archaeological and Naturalist Society and became its first president.

All in all a remarkable and key pioneer in fields crucial to the modern world – information technology, education, scientific research and the free press. His interest in fossil remains as well as flora and sauna pre-dated Darwin and the theory of evolution.

Pocock was essentially a local man and it was his stated belief that “to know the history of our native place should be the first desire of any person possessed in the smallest degree of knowledge”.

Left: William Caxton, the first printer in England

Centre: Robert Pocock

Far right: Charles Darwin.

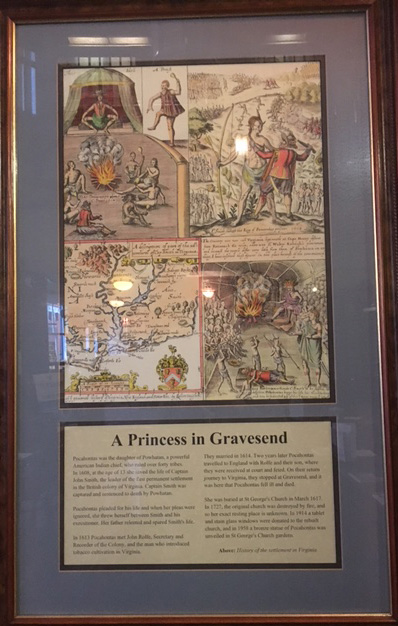

Illustrations and text about Pocahontas.

The text reads: Pocahontas was the daughter of Powhatan, a powerful American Indian chief, who ruled over forty tribes. In 1608, at the age of 13 she saved the life of Captain John Smith, the leader of the first permanent settlement in the British colony of Virginia. Captain Smith was captured and sentenced to death by Powhatan.

Pocahontas pleaded for his life, and when her pleas were ignored, she threw herself between Smith and his executioner. Her father relented and spared Smith’s life.

In 1613 Pocahontas met John Rolfe, secretary and recorder of the colony, and the man who introduced tobacco cultivation in Virginia.

They married in 1614. Two years later Pocahontas travelled to England with Rolfe and their son, where they were received at court and feted.

On their return journey to Virginia, they stopped at Gravesend, and it was here that Pocahontas fell ill and died.

She was buried at St George’s Church in March 1617. In 1727, the original church was destroyed by fire, and so her exact resting place is unknown. In 1914 a tablet and stained-glass windows were donated to the rebuilt church, and in 1958 a bronze statue of Pocahontas was unveiled in St George’s Church gardens.

Above: History of the settlement in Virginia.

An illustration and text about General Charles Gordon.

The text reads: One of Gravesend’s most distinguished residents was General Charles Gordon. He was Royal Engineer officer in command, supervising the construction of forts for the defense of the Thames. This proved to be the longest and happiest posting of his career.

General Gordon arrived in 1865, moving into Fort House. His duties were not arduous and he spent much of his time helping the poor and sick. He divided a great part of his garden into allotments so that poor people could grow their own vegetables. As well as teaching at the Ragged School, he took in poor boys – fed, clothed, and taught them, and later found them jobs.

Charles Gordon was born in 1833. He joined the army and in 1860 he went to China with the Anglo-French Expeditionary Force, where he won the respect of the mandarins and became known as ‘Chinese Gordon’.

After leaving Gravesend he went to the Sudan where he was appointed Governor General. He resigned in 1879, defeated by his own country’s refusal to back his attempts to end the slave trade in Sudan. In 1885 he returned to Sudan to evacuate Khartoum. The siege that followed lasted 317 days, and the end of which Gordon was murdered.

There is a statue of General Gordon in the Gordon Memorial Gardens at the west end of the promenade.

Above: Ragged Children.

Illustrations and text about Gravesend.

The text reads: The history of Gravesend can be traced back to prehistoric times. Excavations have revealed bones, tools and weapons from the Stone Age, as well as coins and pottery from Roman times.

After the Norman Conquest, the Domesday Book records a church and hythe (landing place) at Gravesend. The town’s name derives from the title of the local steward, Portreve, originally Portgereve, and ‘ham’ (village). In the Middle Ages it was called Grevesham, which became Gravesham, the name now used for the borough.

During the 19h century, Gravesend developed as a resort. However, the introduction of the railway in 1849 resulted in fewer visitors as people could travel further afield. Gravesend became more industrial during the latter part of the 19th century with deep water berthing and the building of Tilbury Docks in 1882-86.

Top: Gravesend, c1770

Right: above, the promenade, Milton Place, c1830, below, Gravesend coat of arms.

A photograph of Windmill Street, Gravesend, c1891.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk