This is named after the Franciscan monks (known as Grey Friars from the colour of their habit) who founded a nearby friary in the early 13th century. The friary was founded around 1220. It gave its name to Friargate, but was actually in Marsh Lane (formerly Friars Lane), between Lower Pitt Street and Ladywell Street. The Franciscans, or Grey Friars, are also remembered in the name of this pub.

Prints and text about Preston town centre.

The text reads: During the 19th century the population and the built up area of Preston expanded enormously. By 1850 Chadwick’s orchard, near the present market, was the only green space left in the centre of town.

The covered market, having collapsed and bankrupted the builders, was completed in 1875.

The re-design of the town centre also included the building of the Miller Arcade. With its fashionable shops, the arcade was a forerunner of the modern department store.

By 1875 the new Town Hall, with its tower and clock, had been completed on the south side of the Market Place.

The shops at the Old Shambles on the east side of Market Place were among the buildings demolished in the 1880s, to make way for the Harris Library, Museum & Art Gallery, which was completed in the 1890s.

It was just part of Edmund Harris’ enormous bequest to the town. As well as the library and museum, there was the Harris Orphanage and the Harris Institute.

The latter, with its schools of technology, science and art, was the forerunner of Preston University.

Top: The Town Hall and Market Square

Above: The Harris Library, Museum & Art Gallery.

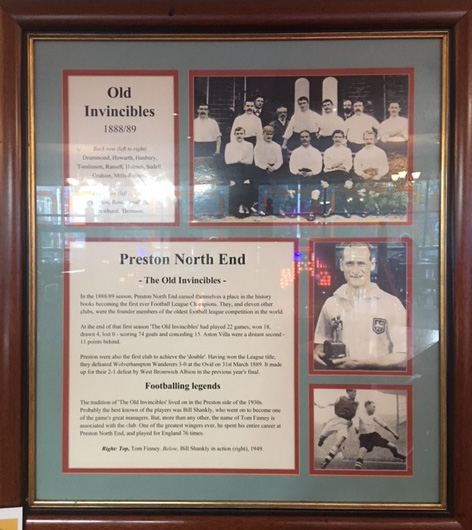

Photographs and text about Preston North End.

The text reads: Old Invincibles, 1888/89

Back row (left to right)

Drummond, Howarth, Hanbury, Tomlinson, Russel, Holmes, Sudell, Graham, Mills-Roberts.

Front row (left to right)

Gordon, Ross, Goodhall, Dewhurst, Thomson.

In the 1888/89 season, Preston North End earned themselves a place in the history books becoming the first ever Football League Champions. They, and eleven other clubs, were the founder members of the oldest football league competition in the world.

At the end of that first season ‘The Old Invincibles’ had played 22 games, won 18, drawn 4, lost 0 – scoring 74 goals and conceding 15. Aston Villa was a distant second – 11 points behind.

Preston were also the first club to achieve the double. Having won the league title, they defeated Wolverhampton Wanderers 3-0 at the Oval on 31 March 1889. It made up for their 2-1 defeat by West Bromwich Albion on the previous years.

Right: top, Tom Finney, below, Bill Shankly in action (right), 1949.

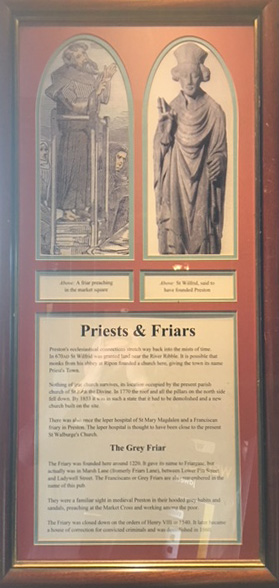

Illustrations and text about priests and friars.

The text reads: Preston’s ecclesiastical connections stretch way back into the mists of time. In 670AD St Wilfrid was granted land near the River Ribbie. It is possible that monks from his abbey at Ripon founded a church here, giving the town its name Priest’s Town.

Nothing of that church survives; its location occupied by the present parish church of St John the Divine. In 1770 the roof and all the pillars on the north side fell down. By 1853 it was in such a state that it had to be demolished and a new church built on the site.

There was also once the leper hospital of St Mary Magdalen and a Franciscan friary in Preston. The leper hospital is thought to have been close to the present St Walburge’s Church.

The friary was founded here around 1220. It gave its name to Friargate, but actually was in Marsh Lane (formerly Friars Lane), between Lower Pitt Street and Ladywell Street. The Franciscans or Grey Friars are also remembered in the name of its pub.

They were a familiar sight in medieval Preston in their hooded grey habits and sandals, preaching at the Market Cross and working among the poor.

The friary was closed down on the orders of Henry VIII in 1540. It later became a house of correction for convicted criminals and was demolished in 1860.

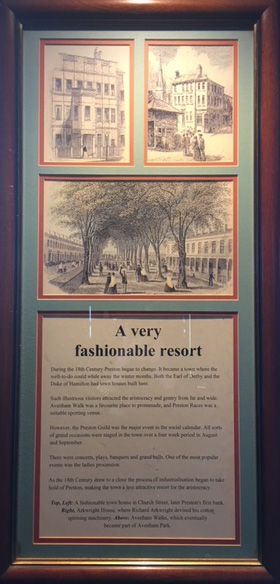

Illustrations and text about Preston as a fashionable resort.

The text reads: During the 18th century Preston began to change. It became a town where the well-to-do could while away the winter months. Both the Earl of Derby and the Duke of Hamilton had town houses built here.

Such illustrious visitors attracted the aristocracy and gentry from far and wide. Avenham Walk was a favourite place to promenade, and Preston Races was a suitable sporting venue.

However, the Preston Guild was the major event in the social calendar. All sorts of grand occasions were staged in the town over a four week period in August and September.

There were concerts, plays, banquets and grand balls. One of the most popular events was the ladies procession.

As the 18th century drew to a close the process of industrialisation began to take hold of Preston, making the town a less attractive resort for the aristocracy.

Top, left: A fashionable town house in Church Street, later Preston’s first bank, right, Arkwright House, where Richard Arkwright devised his cotton spinning machinery, above, Avenham Walks, which eventually became part of Avenham Park.

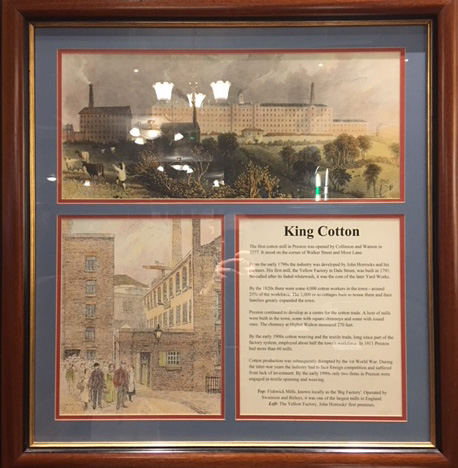

Illustrations and text about cotton production in the area.

The text reads: The first cotton mill in Preston was opened by Collinson and Watson in 1777. It stood the corner of Walker Street and Moor Lane.

From the early 1790s the industry was developed by John Horrocks and his partners. His first mill, the Yellow Factory in Dale Street, was built in 1791. So-called after its faded whitewash, it was the core of the later Yard Works.

By the 1820s there were some 4,000 cotton workers in the town – around 25% of the workforce. The 1,000 or so cottages built to house them and their families greatly expanded the town.

Preston continued to develop as a centre for the cotton trade. A host of mills were built in the town, some with square chimneys and some with round ones. The chimney at Higher Walton measured 270 feet.

By the early 1900s cotton weaving and the textile trade, long since part of the factory system, employed about half the town’s workforce. In 1911 Preston had more than 60 mills.

Cotton production was subsequently disrupted by the 1st World War. During the inter-war years the industry had to face foreign competition and suffered from lack of investment. By the early 1990s only two firms in Preston were engaged in textile spinning and weaving.

Top: Fishwick Mills, known locally as the ‘Big Factory’. Operated by Swainson and Birleys, it was one of the largest mills in England

Left: The Yellow Factory, John Horrock’s first premises.

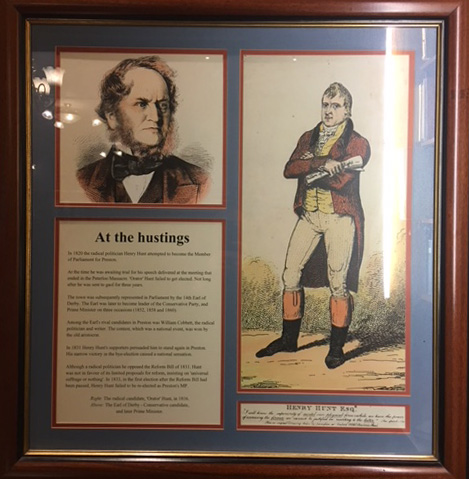

Illustrations and text about Henry Hunt.

The text reads: In 1820 the radical politician Henry Hunt attempted to become the MP for Preston.

At the time he was awaiting trial for his speech delivered at the meeting that ended in the Peterloo Massacre. ‘Orator’ Hunt failed to get elected. Not long after he was sent to gaol for three years.

The town was subsequently represented in Parliament by the 14th Earl of Derby. The earl was later to become leader of the Conservative Party, and Prime Minister on three occasions (1852, 1858 and 1860).

Among the earl’s rival candidates in Preston was William Cobbett, the radical politician and writer. The contest, which was a national event, was won by the old aristocrat.

In 1831 Henry Hunt’s supporters persuaded him to stand again in Preston. His narrow victory in the bye-election caused a national sensation.

Although a radical politician he opposed the Reform Bill of 1831. Hunt was not in favour of its limited proposals for reform, insisting on ‘universal suffrage or nothing’. In 1833, in the first election after the Reform Bill had been passed, Henry Hunt failed to be re-elected as Preston’s MP.

Right: The radical candidate, ‘Orator’ Hunt, in 1816

Above: The Earl of Derby – Conservative candidate, and later prime minister.

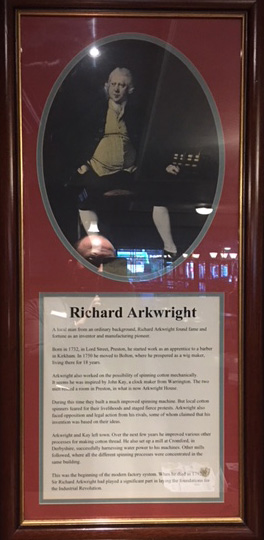

A print and text about Richard Arkwright.

The text reads: A local man from an ordinary background, Richard Arkwright found fame and fortune as an inventor and manufacturing pioneer.

Born in 1732, in Lord Street, Preston, he started work as an apprentice to a barber in Kirkham. In 1750 he moved to Bolton, where he prospered as a wig maker, living there for 18 years.

Arkwright also worked on the possibility of spinning cotton mechanically. It seems he was inspired by John Kay, a clock-maker from Warrington. The two men rented a room in Preston, in what is now Arkwright House.

During this time they built a much improved spinning machine. But local cotton spinners feared for their livelihoods and staged fierce protests. Arkwright also faced an opposition and legal action from his rivals, some of whom claimed that his invention was based on their ideas.

Arkwright and Kay left town. Over the next few years he improved various other processes for making cotton thread. He also set up a mill at Cromford, in Derbyshire, successfully harnessing water power to his machines. Other mills followed, where all the different spinning processes were concentrated in the same building.

This was the beginning of the modern factory system. When he died in 1792, Sir Richard Arkwright had played a significant part in laying the foundations for the Industrial Revolution.

Photographs of Church Street, Preston.

A photograph of the railway station, Preston.

Photographs of Lancaster Road, Preston.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk