283–288 High Holborn, Holborn, London, WC1V 7HP

This pub occupies the ground-floor and cellar of Penderel House, named after Richard Penderel. At the end of the Civil War, in 1652, he helped King Charles II to escape from Cromwell’s troops by hiding the royal fugitive in an oak tree on his country estate.

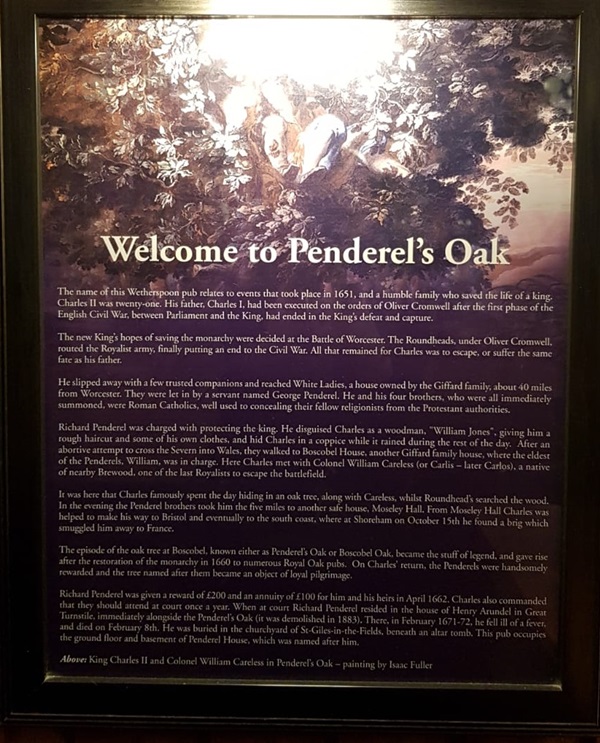

A print and text about The Penderel’s Oak.

The text reads: The name of this Wetherspoon pub relates to events that took place in 1651, and a humble family who saved the life of a king. Charles II was twenty-one. His father, Charles I, had been executed on the orders of Oliver Cromwell after the first phase of the English Civil War, between Parliament and he King, had ended in the King’s defeat and capture.

The new King’s hopes of saving the monarchy were decided at the Battle of Worcester. The Roundheads, under Oliver Cromwell, routed the Royalist army, finally putting an end to the Civil War. All that remained for Charles was to escape, or suffer the same fate as his father.

He slipped away with a few trusted companions and reached White Ladies, a house owned by the Giffard family, about 40 miles from Worcester. They were let in by a servant named George Penderel. He and his four brothers, who were all immediately summoned, were Roman Catholics, well used to concealing their fellow religionists from the Protestant authorities.

Richard Penderel was charged with protecting the king. He disguised Charles as a woodman, “William Jones”, giving him a rough haircut and some of his own clothes, and hid Charles in a coppice while it rained during the rest of the day. After an abortive attempt to cross the Severn into Wales, they walked to Boscobel House, another Giffard family house, where the eldest of the Penderels, William, was in charge. Here Charles met with Colonel William Careless (or Carlis-later Carlos), a native of nearby Brewood, one of the last Royalists o escape the battlefield.

It was here that Charles famously spent the day hiding in an oak tree, along with Careless, whilst Roundhead’s searched the wood. In the evening the Penderel brothers took him the five miles to another safe house, Moseley Hall. From Moseley Hall Charles was helped to make his way to Bristol and eventually to the south coast, where at Shoreham on October 15th he found a brig which smuggled him away to France.

The episode of the oak tree at Boscobel, known either as Penderel’s Oak or Boscobel Oak, became he stuff of legend, and gave rise after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 to numerous Royal Oak pubs. On Charles’ return, the Penderels were handsomely rewarded and he tree named after them became an object of loyal pilgrimage.

Richard Penderel was given a reward of £200 and an annuity of £100 for him and his heirs in April 1662. Charles also commanded that they should attend at court once a year. When at court Richard Penderel resided in the house of Henry Arundel in Great Turnstile, immediately alongside the Penderel’s Oak (it was demolished in 1883). There, in February 1671-72, he fell ill of a fever, and died on February 8. He was buried in the churchyard of St-Giles-in-the-Fields, beneath an altar tomb. This pub occupies the ground floor and basement of Penderel House, which was named after him.

Above King Charles II and Colonel William Careless in Penderel’s Oak – painting by Isaac Fuller.

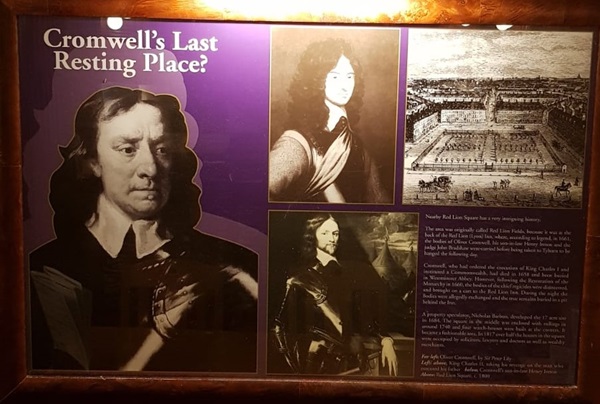

Prints and text about Oliver Cromwell.

The text reads: Nearby Red Lion Square has a very intriguing history.

The area was originally called Red Lion Fields, because it was at the back of the Red Lion (Lyon) Inn, where, according to legend, in 1661, the bodies of Oliver Cromwell, his son-in-law Henry Ireton and the judge John Bradshaw were carried before being taken to Tyburn to be hanged the following day.

Cromwell, who had ordered the execution of King Charles I and instituted a Commonwealth, had died in 1658 and been buried in Westminster Abbey. However, following the Restoration of the Monarch in 1660, the bodies of the chief regicides were disinterred, and brought on a car to the Red Lion Inn. During the night the bodies were allegedly exchanged and the true remains buried in a pit behind the Inn.

A property speculator, Nicholas Barbon, developed the 17acre site in 1684. The square in the middle was enclosed with railings in around 1740 and four watch-houses were built at the corners. It became a fashionable area. In 1817 over half the houses in the square were occupied by solicitors, lawyers and doctors as well as wealthy merchants.

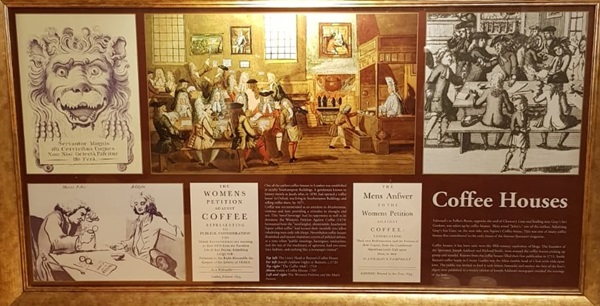

Prints and text about coffee houses.

The text reads: One of the earliest coffee-houses in London was established in nearby Southampton buildings. A gentleman known to history merely as Jacob, who in 1650, had opened a ‘coffee house’ in Oxford, was living in Southampton Buildings, and selling coffee there, by 1671.

Coffee was recommended as an antidote to drunkenness, violence and lust; providing stimulus to thought and wit. This ‘novel beverage’ had its opponents as well as its devotees; the Women’s petition Against Coffee (1674) bemoaned how he “new-fangled, abominable, heathenish liquor called coffee” had turned their menfolk into idlers inhabiting men only talk-shops. Nevertheless coffee houses flourished and became important centres of political debate, at a time when “public meetings, harangues, resolutions, and he rest of the machinery of agitation, had not come into fashion, and nothing like a newspaper existed”.

Fulwood’s or Fuller’s Rents, opposite the end of Chancery Lane and leading into Gray’s Inn Gardens, was taken up by coffee houses. Here stood “John’s,” one of the earliest. Adjoining Gray’s Inn Gate, on the west side was Squire’s Coffee-house. This was one of many coffee houses that contributed to the early issues of the famous Spectator magazine.

Coffee houses, it has been said, were the 18th century equivalent of blogs. The founders of the Spectator, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, went around the coffee houses picking up gossip and scandal. Reports from the coffee houses filled their first publication in 1711. Inside Button’s coffee house in Covent Garden was the white marble head of a lion with wide-open jaws. The public was invited to feed it with letters, limericks and stories; the best of the lion’s digest were published in a weekly edition of Joseph Addison’s newspaper, entitled ‘the roaring of the lion’.

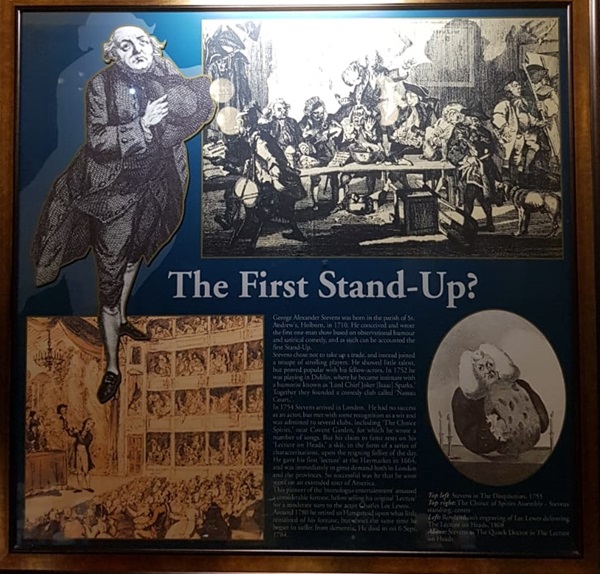

Prints and text about the first stand up.

The text reads: George Alexander Stevens was born in the parish of St. Andrew’s, Holborn, in 1710. He conceived and wrote the first one-man show based on observational humour and satirical comedy, and such can be accounted the first stand-up.

Stevens chose not to take up a trade, and instead of joined a troupe of strolling players. He showed little talent, but proved popular with his fellow-actors. In 1752 he was playing in Dublin, where he became intimate with a humourist known as `Lord Chief Joker [Isaac] Sparks.’ Together they founded a comedy club called `Nassau Court,’.

In 1754 Stevens arrived in London. He had no success as an actor, but met with some recognition as a wit and was admitted to several clubs, including `The Choice Spirits.’ Near Covent Garden, for which he wrote a number of songs. But his claim to fame rests on his `Lecture on Heads,’ a skit, in the form of a series of characterisations, upon the reigning follies of the day. He gave his first `lecture’ at the Haymarket in 1664, and the provinces. So successful was he that he son went on an extended tour of America.

This pioneer of the `monologue entertainment’ amassed a considerable fortune, before selling his original `Lecture’ for a moderate sum to the actor Charles Lee Lewes. Around 1780 he retired to Hampstead upon what little remained of his fortune, but about the same time he began to suffer from dementia. He died in on 6 Sept. 1784.

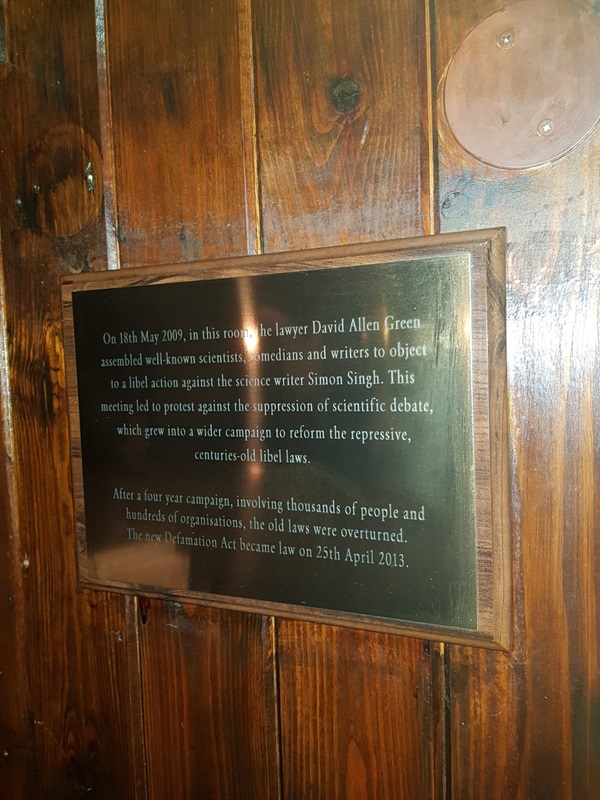

A plaque dedicated to David Allen Green and the new Defamation Act.

The plaque reads: On 18 May 2009, in this room, the lawyer David Allen Green assembled well-known scientists, comedians and writers to object to a libel action against the science writer Simon Singh. This meeting led to protest against the suppression of scientific debate, which grew into a wider campaign to reform the repressive centuries-old libel laws.

After a four year campaign, involving thousands of people and hundreds of organisations, the old laws were overturned. The new Defamation Act became law on 5 April 2013.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk