This pub stands at the northwest corner of the former Import Dock. It takes its name from the building’s original use, to house the ledgers of the West India Docks.

Framed prints and text about The Ledger Building.

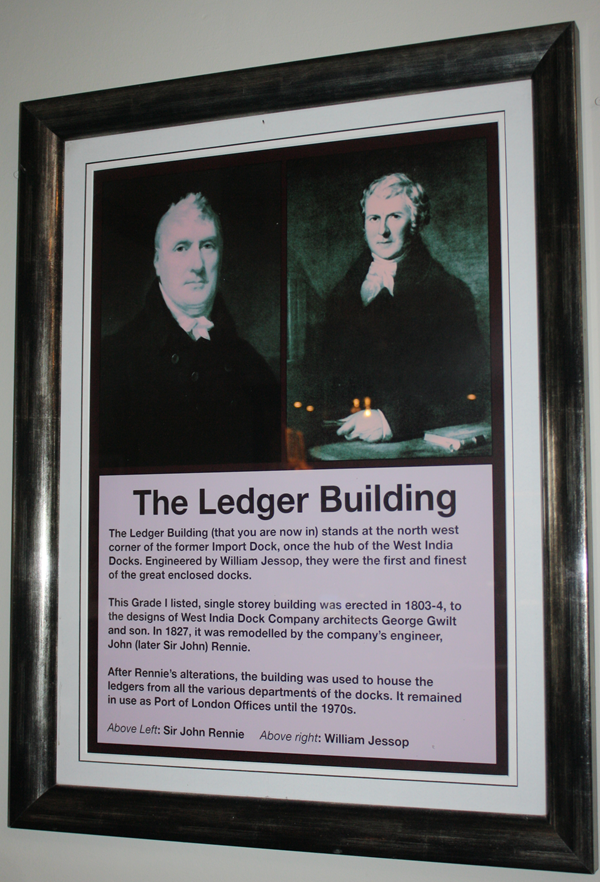

The text reads: The Ledger Building (that you are now ¡n) stands at the north west corner of the former Import Dock, once the hub of the West India Docks. Engineered by William Jessop, they were the first and finest of the great enclosed docks.

This Grade I listed, single storey building was erected in 1803-4, to the designs of West India Dock Company architects George Gwilt and son. In 1827, it was remodelled by the company’s engineer, John (later Sir John) Rennie.

After Rennie’s alterations, the building was used to house the ledgers from all the various departments of the docks. It remained in use as Port of London Offices until the 1970s.

Above Left: Sir John Rennie

Above right: William Jessop.

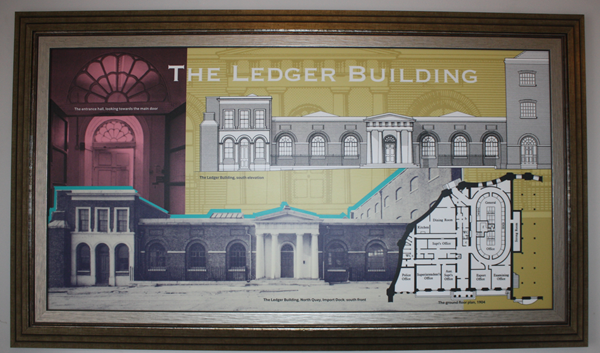

A framed collection of photographs and illustrations of the building.

Images are captioned (clockwise from top left): ‘The entrance hall, looking towards the main door’; ‘The Ledger Building, south elevation’; ‘The ground floor plan, 1904’; The Ledger Building, North Quay, Import Dock: south front’.

A framed passage about the sugar trade.

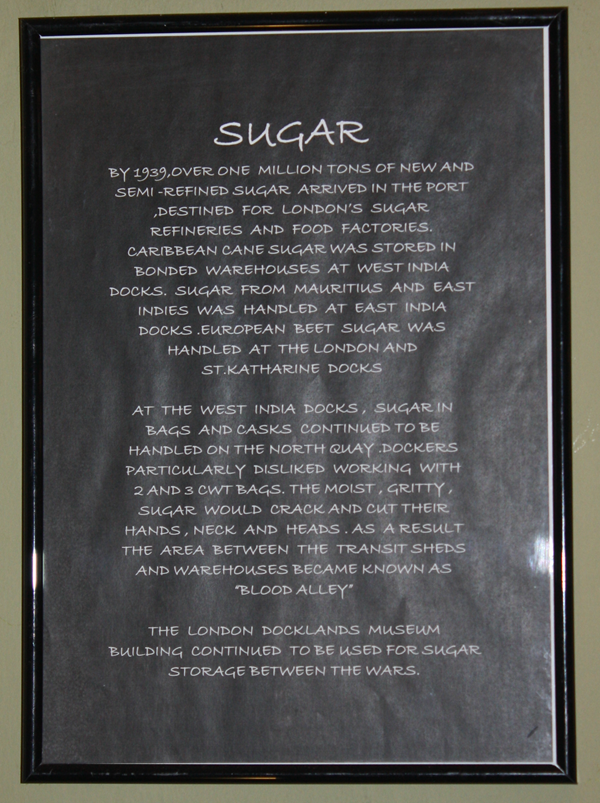

The text reads: By 1939, over one million tons of new and semi-refined sugar arrived in the port, destined for London’s sugar refineries and food factories. Caribbean cane sugar was stored in bonded warehouses at West India Docks. Sugar from Mauritius and East Indies was handled at East India Docks. European beet sugar was handled at the London and St Katherine Docks.

At the West India Docks, sugar in bags and casks continued to be handled on the North Quay. Dockers particularly disliked working with 2 and 3 CWT bags. The moist, gritty, sugar would crack and cut their hands, neck and heads. As a result the area between the transit sheds and warehouses became known as “Blood Alley”.

The London Docklands Museum building continued to be used for sugar storage between the wars.

A framed passage about the grain trade.

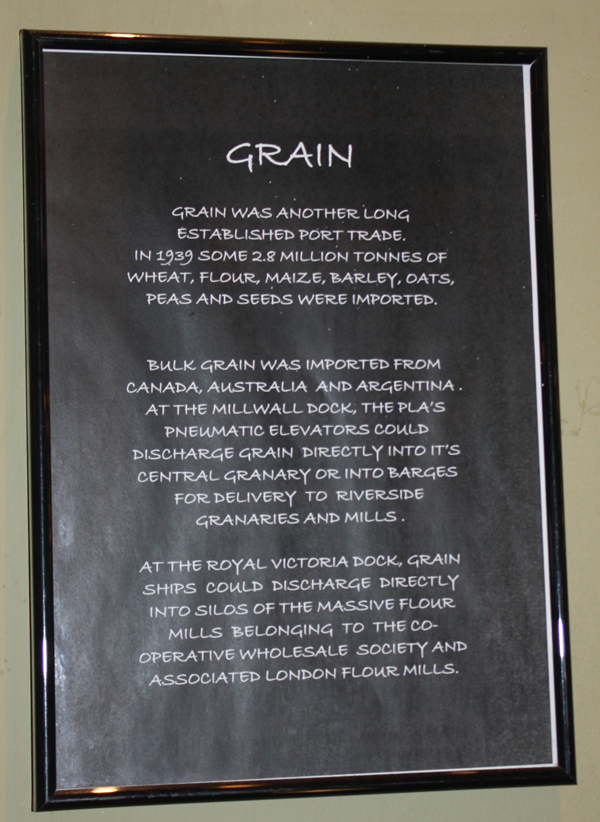

The text reads: Grain was another long established port trade. In 1939 some 2.8 million tonnes of wheat, flour, maize, barley, oats, peas and seeds were imported.

Bulk grain was imported from Canada, Australia and Argentina. At the Millwall Dock, the PLA’s pneumatic elevators could discharge grain directly into its central granary on into barges for delivery to riverside granaries and mills.

At the Royal Victoria Dock, grain ships could discharge directly into silos of the massive flour mills belonging to the co-operative wholesale society and associated London flour mills.

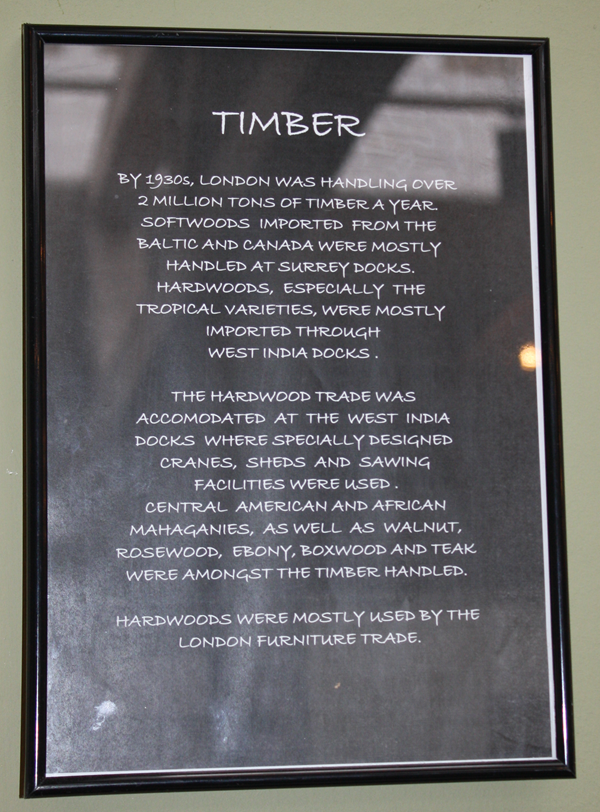

A framed passage about the timber trade.

The text reads: By 1930s, London was handling over 2 million tons of timber a year. Softwoods imported from the Baltic and Canada were mostly handled at Surrey Docks. Hardwoods, especially the tropical varieties, were mostly imported through West India Docks.

The hardwood trade was accommodated at the West India Docks where specially designed cranes, sheds and sawing facilities were used. Central American and African mahoganies, as well as walnut, rosewood, ebony, boxwood and teak were amongst the timber handled.

Hardwoods were mostly used by the London furniture trade.

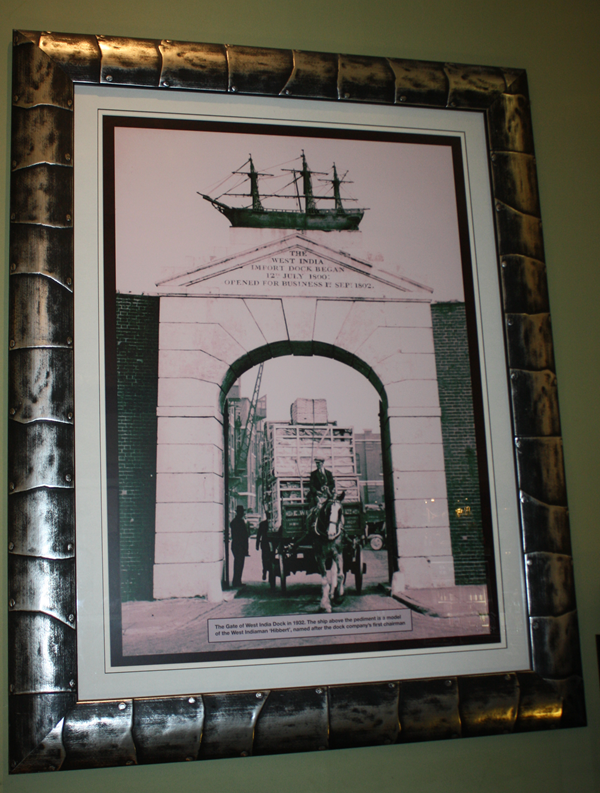

A framed photograph of the Gate of West India Dock, in 1932. The ship above the pediment is a model of the West Indiaman ‘Hibbert’, named after the dock company’s first chairman.

A framed photograph of South West India Dock’s western entrance, with barges waiting to leave the dock, in 1877.

A framed collection of photographs and text about the SS Great Eastern.

The text reads: Brunel’s Magnificent Failure

At the South Eastern tip of Millwall, near Canary Wharf, lie the remains of the ramp built to launch Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s SS Great Eastern. Built to carry passengers and cargo to and from Australia and America, at the time of her launch in 1858 SS Great Eastern was the largest ship ever built, and the first to be constructed almost entirely of metal.

The huge ship was built here mainly for financial reasons. Brunel and his partner Scott Russell, unable to afford a new dock, used “Napier Yard”, next to Scott Russell’s own Millwall Dock. Napier Yard was also next to the Millwall iron Works (also owned by Scott Russell), and Millwall had a highly skilled shipbuilding workforce.

Work began in the spring of 1854 and was completed by November 1857. Because the ship was too long to launch front first, it was planned to launch it sideways. On the first attempt the ship did not move. It took another three attempts and three months to finally get her into the water.

Great eastern was a commercial failure, but finally found a role when, in April 1864, as the only ship big enough for the job, she was chartered to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable. She ended her days in August 1888, when she was sold for scrap.

Top left: An attempted launch of the Great Eastern

Top right: Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 1858

Centre: The Great Eastern on the slipway at the Napier Yard, 1857

Left: The ship finally afloat

Left: The Great Eastern at sea.

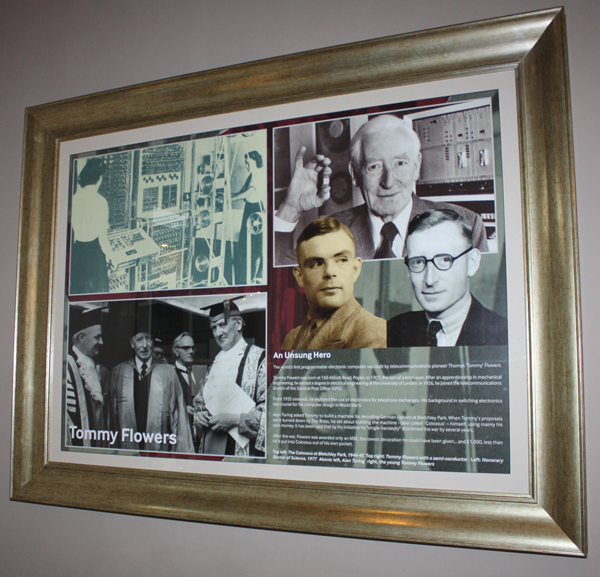

A framed collection of photographs and text about Tommy Flowers.

The text reads: The world’s first programmable electronic computer was built by telecommunications pioneer Thomas ‘Tommy’ Flowers.

Tommy Flowers was born at 160 Abbott Road, Poplar, in 1905, the son of a bricklayer. After an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering, he earned a degree in electrical engineering at the University of London. In 1926, he joined the telecommunications branch of the General Post Office (GPO).

From 1935 onwards, he explored the use of electronics for telephone exchanges. His background in switching electronics was crucial for his computer design in World War II.

Alan Turing asked Tommy to build a machine for decoding German ciphers at Bletchley Park. When Tommy’s proposals were turned down by Top Brass, he set about building the machine – later called ‘Colossus’ – himself, using mainly his own money. It has been said that by his initiative he “single-handedly” shortened the war by several years.

After the war, Flowers was awarded only an MBE, the lowest decoration he could have been given… and £1,000, less than he’d put into Colossus out of his own pocket.

Top left: the Colossus at Bletchley Park, 1944-45

Top right: Tommy Flowers with a semi-conductor

Left: Honorary Doctor of Science, 1977

Above: left, Alan Turing right, the young Tommy Flowers.

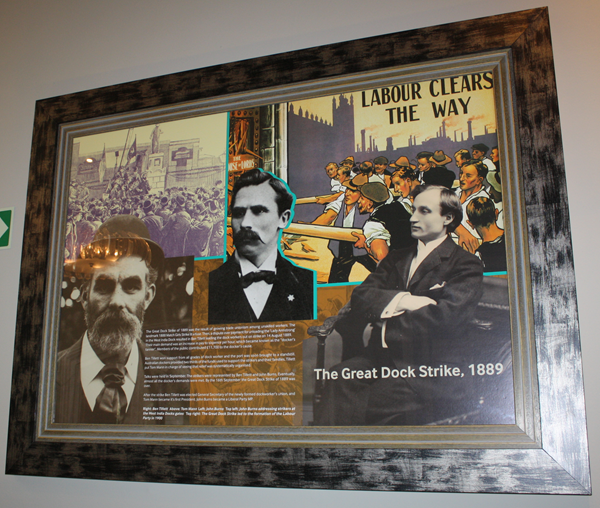

A framed collection of photographs and text about The Great Dock Strike of 1889.

The text reads: The Great Dock Strike of 1889 was the result of growing trade unionism among unskilled workers. The landmark 1888 Match Girls Strike lit a fuse. Then, a dispute over payment for unloading the ‘Lady Armstrong’ in the West India Dock resulted in Ben Tillett leading the dock workers out on strike on 14 August 1889. Their main demand was an increase in pay to sixpence per hour, which became known as the “docker’s tanner”. Members of the public contributed £11,700 to the docker’s cause.

Ben Tillet won support from all grades of dock worker and the port was soon brought to a standstill. Australian dockers provided two thirds of the funds used to support the strikers and their families. Tillett put Tom Mann in charge of seeing that relief was systematically organised.

Talks were held in September. The strikers were represented by Ben Tillet and John Burns. Eventually, almost all the docker’s demands were met. By the 16th September the Great Dock Strike of 1889 was over.

After the strike Ben Tillet was elected General Secretary of the newly formed dockworker’s union, and Tom Mann became its first President. John Burns became a Liberal Party MP.

Right: Ben Tillett

Above: Tom Mann

Left: John Burns

Top left: John Burns addressing strikers at the West India Docks gates

Top right: The Great Dock Strike led to the formation of the Labour Party in 1900.

A framed illustration of the statue of Robert Milligan (c1746–1809).

The text reads: Milligan, a wealthy West India merchant and ship-owner headed a group of powerful businessmen who planned and built west India Docks. Opened on the 27th August 1802, these docks were the largest structure of their kind anywhere in the world. Milligan served as both Deputy Chairman and Chairman of the West India Dock company.

A framed photograph of George Hibbert.

The text reads: George Hibbert, promoter and first Chairman of the West India Dock Company, from a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1812.

Framed photographs and text about Will Crooks.

The text reads: Born in Shirbutt Street, Poplar, in 1852, Will Crooks was the third son of a ship’s stoker. When Will was three, his father lost an arm in an accident and his mother had to support the family. In 1861 five of her children were forced to enter Poplar Workhouse.

Educated at a local poor law school, Crooks was a keen reader. He found work in the docks and developed his speaking skills outside the East India Dock gates. During the 1889 London Dock Strike his speeches helped raise funds for 10,000 striking dockers.

Crooks became one of the first Labour members on the London County Council, where he was instrumental in giving Londoners the Rotherhithe Tunnel and the Greenwich and Woolwich foot tunnels. One of the Woolwich Ferries was later named after him.

He later became chairman of the Poplar Board of Guardians, the same board that had put him and his siblings in the workhouse. Supported by George Lansbury, Crooks set about reforming the local workhouse, creating a model for other poor law authorities.

In 1900 Crooks became the first Labour Mayor of Poplar, and two years later was elected for Woolwich as only the fourth ever Labour MP. He fought for the introduction of the National Old Age Pension scheme and was mainly responsible for unemployment becoming a government responsibility. He was calling for a minimum wage in parliament 86 years before Tony Blair’s government first introduced one.

Top left: The Crooks family (Will looking over his father’s left shoulder)

Top right: “I am a Poplar man. I was born in Poplar in poverty”, 1917

Left: Mr and Mrs Will Crooks.

A framed photograph of Port of London Authority policemen testing life-jackets by jumping into West India Docks, in c1930.

A framed collection of photographs and text about The Singing Pub.

The text reads: The Isle of Dogs was, for a short while, a mecca for the world’s greatest entertainers.

Photographer and TV documentary maker Daniel Farsons set up home in nearby Narrow Street in the late 1950’s. In 1962, he made a documentary about pub entertainment in the East End called Time Gentlemen Please and in the same year set up a “singing pub”. The Waterman’s Arms, on the Isle of Dogs, intending to revive old-time music hall.

The Waterman’s proved a draw for everybody who was anybody in show business – Francis Bacon brought William Burroughs to join Jacques Tati, Shirley Bassey, Clint Eastwood, Judy Garland, Groucho Marx, Lord Snowden, Tony Bennett, Annie Ross, George Melly – the list goes on…

But Farsons was mainly concerned with reviving interest in the great music hall stars, and reviving the careers of survivors from the ‘Good Old Days’. He dusted off memories of the great Marie Lloyd, who he said “represented the particular qualities of East-Enders that defiance…and the wish to better themselves”. Marie was dead by 1922 but some of the old music hall stars were still alive. Farson’s obsession with music hall was kindled by Ida Barr. Along with Joan Littlewood he re-discovered and brought a late flowering of fame to a star who had faded. Ida – ‘I may not be spring chicken, but I’m still game’ – weighed well over 13 stone in her prime ‘they liked a lot of woman in those days’. Her six feet of solid femininity prompted the comment ‘Ida Bar? She could ‘ide a bloomin’ pub’.

Ida became a star in America and returned with songs like ‘Oh. You Beautiful Doll’ and ‘Everybody’s Doin’ It Now’. Unlikely as it may seem, you could, for a brief period in the early 1960’s have heard Ida, in her eighties, and Judy Garland, in her prime, both belting out their songs in an Isle of Dogs bar, just for the fun of it.

Top left: Marie Lloyd Top right: The formidable figure of Ida Barr, aged sixteen Far left: Daniel Farsons (left), at the Waterman’s Arms with Sean Lynch, Annie Ross and Tony Bennett Left: Ida Barr during the late revival of her career.

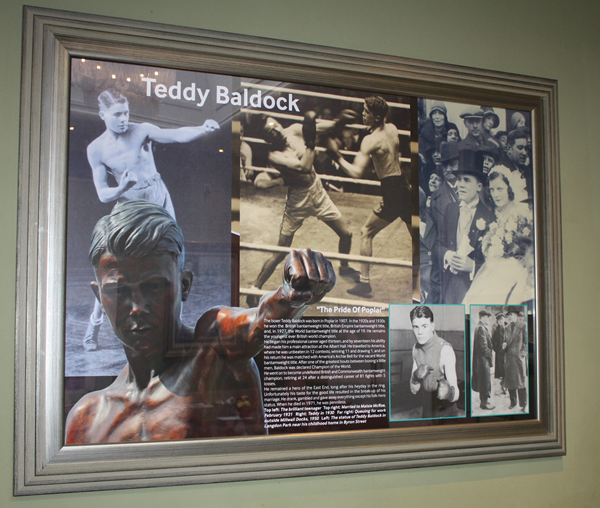

A framed collection of photographs and text about Teddy Baldock.

The text reads: The boxer Teddy Baldock was born in Poplar in 1907. In the 1920s and 1930s he won the British bantamweight title, British Empire bantamweight title, and, in 1927, the World bantamweight title at the age of 19. He remains the youngest ever British world champion.

He began his professional career aged thirteen, and by seventeen his ability had made him a main attraction at the Albert Hall. He travelled to America, where he was unbeaten in 12 contests, winning 11 and drawing 1, and on his return he was matched with America’s Archie Bell for the vacant World bantamweight title. After one of the greatest bouts between boxing’s little men, Baldock was declared Champion of the World.

He went on to become undefeated British and commonwealth bantamweight champion, retiring at 24 after a distinguished career of 81 fights with 5 losses.

He remained a hero of the East End, long after his heyday in the ring. Unfortunately his taste for the good life resulted in the break-up of his marriage. He drank, gambled and gave away everything except his folk-hero status. When he died in 1971, he was penniless.

Top left: The brilliant teenager Top right: Married to Maisie McRae, February 1931 Right: Teddy in 1930 Far right: Queuing for work outside Millwall Docks, 1950 Left: The statue of Teddy Baldock in Langdon Park near his childhood home in Byron Street.

A framed collection of photographs and a map of Poplar, Blackwall and The Isle of Dogs: The Parish of All Saints.

The photos are captioned: (top left) ‘The Penang, in Britannia Dry Dock, towers over backyards in Millwall, c.1930’; (centre left) ‘North side of Pennyfields, c. 1925’; (bottom left) ‘All Saints’ Church and Newby Place, c. 1908’; (bottom right) ‘Poplar High Street and Pennyfields, c. 1890’.

A framed collection of photographs and text about The Isle of Dogs.

The text reads: Until 1800 the isle of Dogs, also known by its original name of Stebunheath or Stepney Marsh, was pastureland. It was protected from the high tides of the River Thames by a great bank of earth, wood and stones, erected in the distant past.

From time to time the river broke through this bank and flooded parts of the Island; on one occasion it left a permanent inland lake, called The Breach, or Poplar Gut. Windmills for grinding corn were built on the western side of the bank between 1680 and 1720, giving the area its name: Millwall.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, ship-building began in Limehouse and Blackwall. The West India merchants, whose sugar ships came crowding up the river, petitioned Parliament for permission to build enclosed docks across the northern end of the Isle of Dogs, and the West India Docks were opened in 1802. The Museum of London Docklands, next door to the Ledger Building, is housed in some of the original sugar warehouses.

Skilled workers and labourers came to Millwall to live. The name “Millwall” became associated with the most advanced engineering of the day, leading to the construction of Brunel’s famous and ill-fated Great Eastern steamship in the 1850s.

Shipbuilding declined in the 1860s, but engineering, chemical works and food processing flourished.

By the end of the 19th century , the Island population was over 21,000 and the foreshore was a wall of factories and workshops. This was not to last and the 1970s saw a general economic downturn. By the early 1980s the West India and Millwall docks had closed.

The Island became a place of still waters, rusting cranes and derelict riverside sites. After prolonged debate about what to do with ‘Docklands’, as the area was designated, the government created the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) and a new city was created.

The photos are captioned (clockwise, from top left): ‘West India Docks, Import Dock, 1921’; ‘Canary Wharf, 1991’; ‘Canary Wharf, 1989’; ‘west India Docks, looking towards the City of London, 1986’.

A framed photograph captioned North Quay of the Export Dock, c1935; bananas being loaded onto rail trucks.

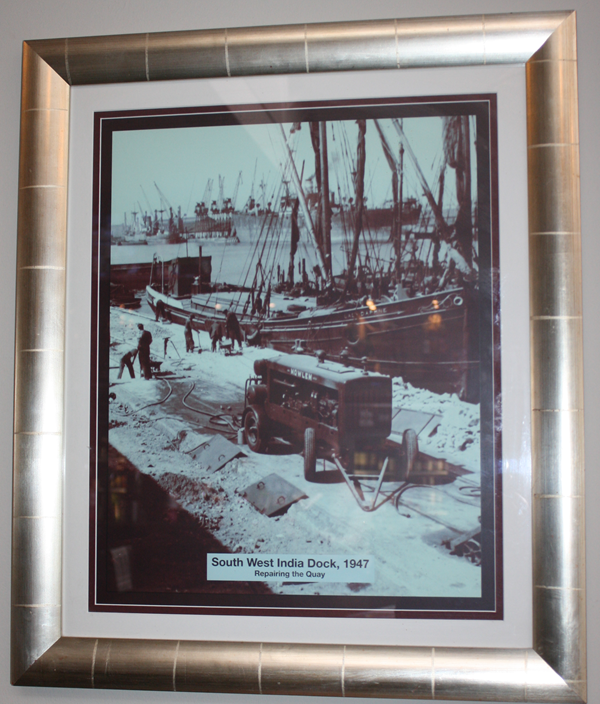

A framed photograph captioned South West India Dock, 1947; Repairing the Quay.

A framed painting captioned The opening of the West India Docks, 1802. The Henry Addington, decorated with the Colours of all Nations.

A framed photograph entitled Blood Alley, c1930.

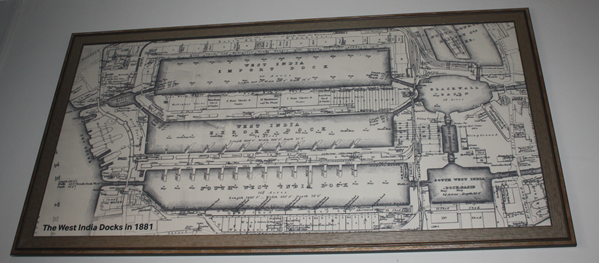

A framed map of The West India Docks, in 1881.

A framed photograph of boats on the Thames, with Tower Bridge in the background.

A framed photograph of a ship in the West India Docks.

A framed photograph of the Eastern Hotel, West India Dock Road.

A framed photograph of Poplar Rail Station.

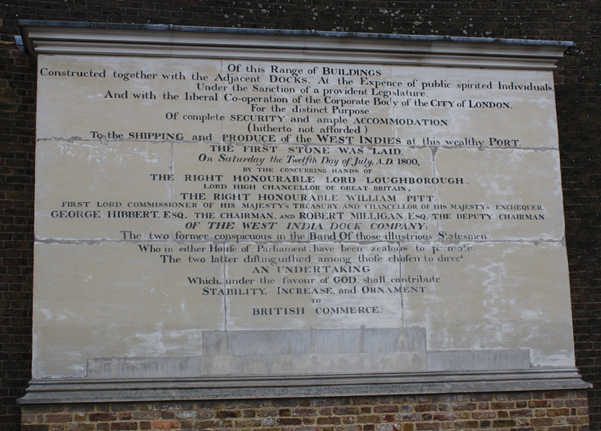

A plaque located on the side of The Ledger Building.

The text reads: Of this range of buildings constructed together with the Adjacent Docks. At the expence of public spirited individuals. Under the Sanction of a provident Legislature. And with the liberal Co-operation of the Corporate Body of the City of London. For the distinct Purpose Of complete security and ample accommodation (hitherto not afforded)

To the shipping and produce of the west Indies at this wealthy port. The first stone was laid On Saturday the Twelfth Day of July A.D. 1800, by the concurring hands of The Right Honourable Lord Loughborough. Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, The Right Honourable William Pitt first lord commissioner of his majesty’s treasury and chancellor of his majesty’s exchequer. George Hibbert, Esq, the chairman, and Robert Milligan, Esq, The Deputy Chairman of the West India Dock Company: The two former conspicuous in the Band Of those illustrious Statesmen. Who in either House of Parliament, have been zealous to promote The two latter distinguished among those chosen to direct an undertaking Which, under the favour of God, shall contribute stability, increase and ornament to British Commerce.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk