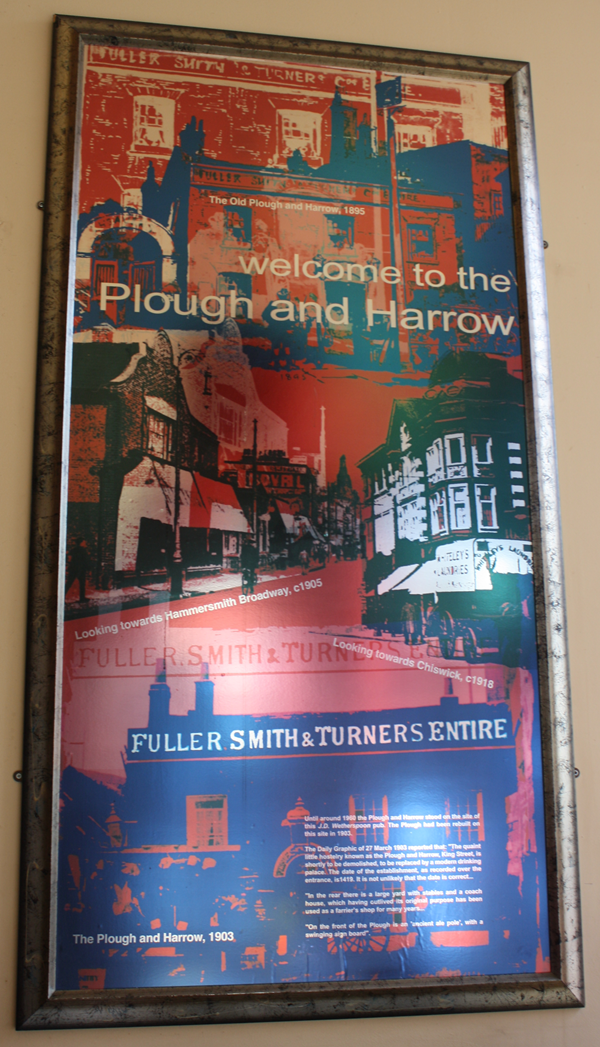

This pub is on the site of The Plough and Harrow Inn which stood here until c1960. Rebuilt in 1903, The Plough and Harrow replaced a centuries-old pub of the same name. Before then, it had ‘Established in 1419’ painted above the entrance.

Framed prints and text about The Plough and Harrow.

The text reads:

Until around 1960 The Plough and Harrow stood on the site of this J.D. Wetherspoon pub. The Plough had been rebuilt on this site in 1903.

The Daily Graphic of 27 March 1903 reported that “The quaint little hostelry known as The Plough and Harrow, King Street is shortly to be demolished, to be replaced by a modern drinking place. The date of the establishment, as recorded over the entrance, is 1419. It is not unlikely that the date is correct…

In the rear is a large yard with stables and a coach house, which having cultivated its original purpose has been used as a farmer’s shop for many years…

“On the front of the Plough is an ancient ale pole with a swinging sign board”.

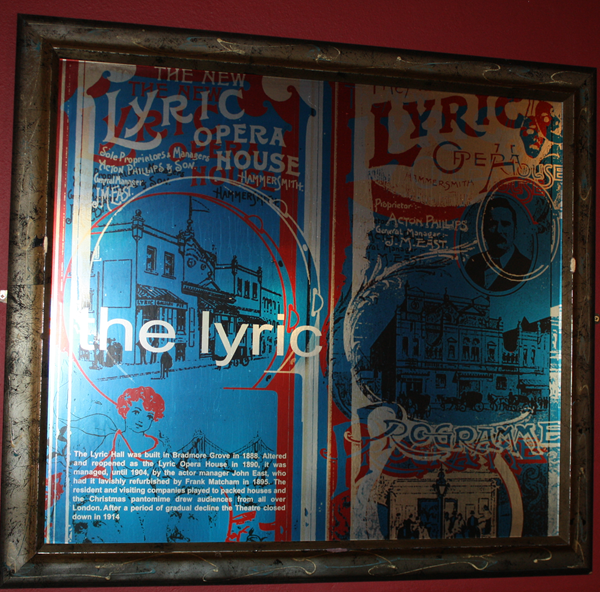

Framed prints and text about The Lyric Hall.

The text reads: The Lyric Hall was built in Bradmore Grove in 1888. Altered and reopened as the Lyric Opera House in 1890, it was managed, until 1904, by the actor manager John East, who had it lavishly refurbished by Frank Matcham in 1895. The resident and visiting companies played to packed houses and the Christmas pantomime drew audiences from all over London. After a period of gradual decline the Theatre closed down in 1914.

Framed prints and text about The Lyric Hall.

The text reads: Nigel Playfair went to the decrepit Lyric to hire some scenery and ended up buying the theatre. He reopened the venue in 1918 with A.A.Milne’s Make Believe and inaugurated two decades of theatrical splendour. The Beggars Opera ran for three and a half years. Stars were born, such as Edith Evans, John Gielgud and Sybil Thorndike. A decline in the late 1930’s was followed, after the war by a new golden era, until the redevelopment of the Kings Mall area. A public campaign to save the interior failed, was rewarded in 1979 by the building of the new Lyric.

Framed prints and text about the early days in Hammersmith.

The text reads: In the south east corner of St Paul’s church, beneath a bust of King Charles 1st, is an urn. Inside the urn is the heart of Sir Nicholas Crisp. Sir Nicolas supported the Royalist cause during the English civil war, with wealth largely obtained by slave trading out of Guinea under a monopoly granted by the King. His dying request was “let my heart be placed…at my masters feet”.

In exile after the King was beheaded, he “investigated all foreign improvements and turned them to English uses”. On his return he introduced the art of brickmaking here, as well as new farming and milling methods.

The name of Hammersmith, first recorded in 1294, comes from its forge and smithy by the river. For centuries the area was owned by the Bishops of London, as part of the Manor of Fulham.

Perrers Road, not far from this pub, recalls Alice Perrers, mistress of King Edward 111. The King granted her the mansion and land in what is now Ravenscourt Park. The area received its present name in the 18th century from the coat of arms of its owner, Thomas Corbett, secretary to the Admiralty.

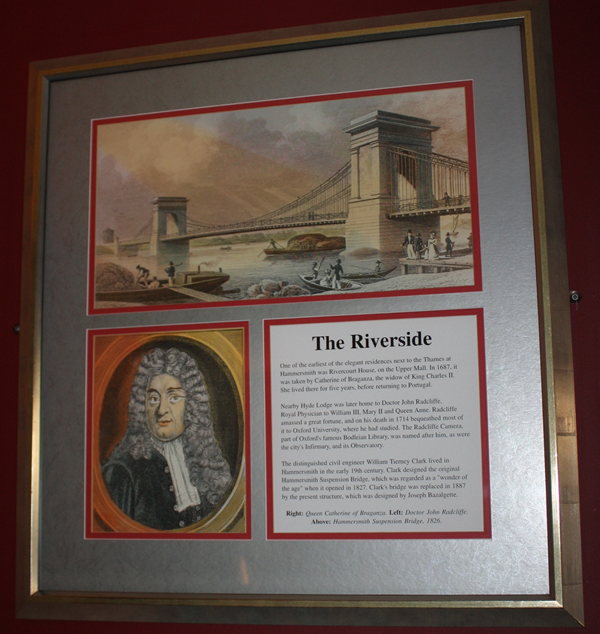

Framed drawings and text about the Thames.

The text reads: One of the earliest of the elegant residences next to the Thames at Hammersmith was Rivercourt House, on the Upper Mall. In 1687, it was taken by Catherine of Braganza, the widow Of King Charles 11. She lived there for five years, before returning to Portugal.

Nearby Hyde Lodge was later home to Doctor John Radcliffe, Royal Physician to William 111. Mary 11 and Queen Anne. Radcliffe amassed a great fortune, and on his death in 1714 bequeathed most of it to Oxford University, where he had studied. The Radcliffe Camera, part of Oxford’s famous Bodleian Library, was named after him, as were the city’s Infirmary, and its Observatory.

The distinguished civil engineer William Tierney Clark lived in Hammersmith in the early 19th century. Clark designed the original Hammersmith suspension bridge, which was regarded as a “wonder of the age” when it opened in 1827. Clark’s bridge was replaced in 1887 by the present structure which was designed by Joseph Bazalgette.

Framed prints and text about trade and industry.

The text reads: Brick-making is probably the oldest industry in Hammersmith, dating back to the 17th century.

In the late 18th century James Cromwell established a brewery on what is now the site of the Town Hall, not far from the mouth of the Creek and High Bridge. Cromwell dressed shabbily and worked alongside his men. He also ate the same simple food and drink as they did.

In 1816 he was taken ill, and it was discovered that he had bank notes worth £1.400 in his pockets.

Cromwell oast houses could be seen beside the river until the twentieth century, although by then the firm was known as Swail’s Brewery. The name of this well-known local brewer is now preserved in Cromwell Mansions.

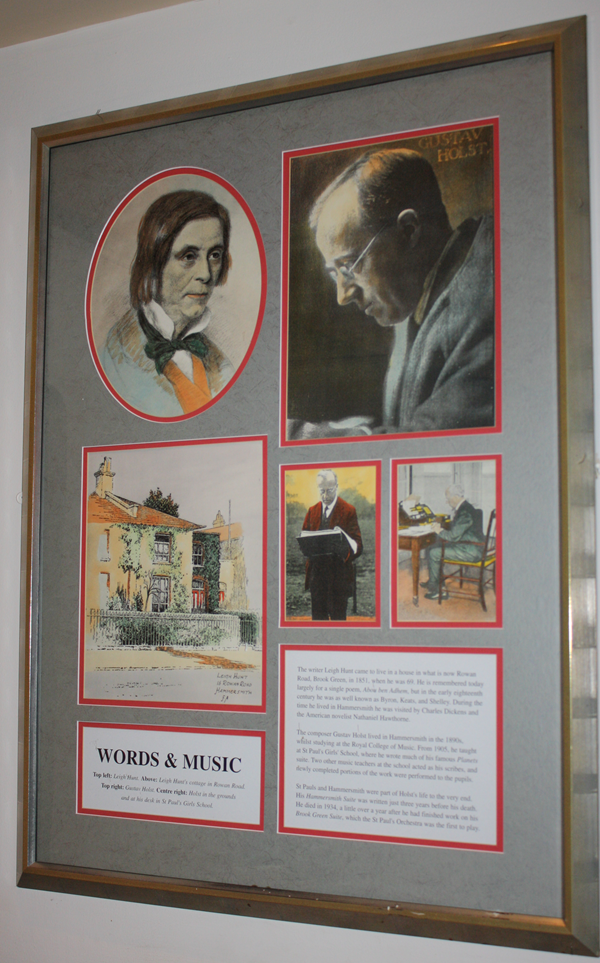

Framed prints and text about literature and music in Hammersmith.

The text reads: The writer Leigh Hunt came to live in a house in what is now Rowan Road, Brook Green, in 1851, when he was 69. He is remembered today largely for a simple poem. Abou ben Adhem, but in the early eighteenth century he was well known as Byron, Keats and Shelly. During the time he lived in Hammersmith he was visited by Charles Dickens and the American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The composer Gustav Holst lived in Hammersmith in the 1890’s whilst studying at the Royal College of Music. From1905, he taught at St Paul’s Girls School, where he wrote much of his famous Planets suite. Two other music teachers at the school acted as his scribes, and newly completed portions of the work were performed to the pupils.

St Pauls and Hammersmith were part of Holst’s life to the very end. His Hammersmith Suite was written just three years before his death. He died in 1934, a little over a year after he had finished work in his Brook Green Suite, which the St Pauls Orchestra was the first to play.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk