This pub is closed permanently. Your nearest Wetherspoon pub: The Moon & Stars

The name of this pub recalls the site’s long history as a post office. The ‘Chief District Post & Telegraph Office’ stood here before World War I; by the 1950s, it was in use as the post office sorting rooms.

Prints and text about The Postal Order.

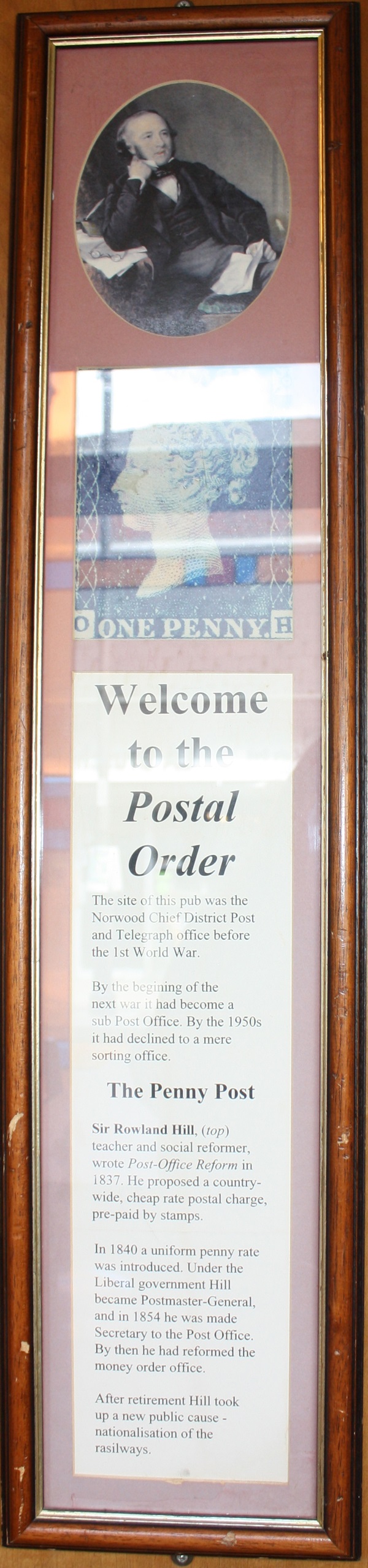

The text reads: The site of this pub was the Norwood Chief District Post and Telegraph office before the First World War.

By the beginning of the next war it had become a sub Post Office. By the 1950s it had declined to a mere sorting office.

Sir Rowland Hill, teacher and social reformer, wrote Post-Office Reform in 1837. He proposed a country-wide, cheap rate postal charge, pre-paid by stamps.

In 1840 a uniform penny rate was introduced. Under the Liberal government Hill became Postmaster-General, and in 1854 he was made secretary to the Post Office. By then he had reformed the money order office.

After retirement Hill took up a new public cause- nationalisation of the railways.

Prints and text about Henry Coxwell.

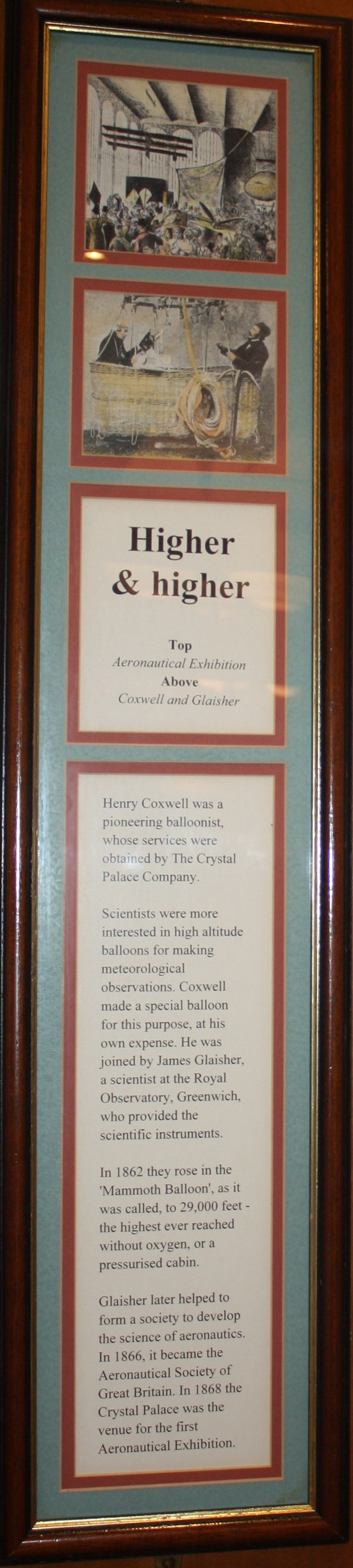

The text reads: Henry Coxwell was a pioneering balloonist, whose services were obtained by The Crystal Palace Company.

Scientists were more interested in high altitude balloons for making meteorological observations. Coxwell made a special balloon for this purpose, at his own expense. He was joined by James Glaisher, a scientist at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, who provided the scientific instruments.

In 1862 they rose in the ‘Mammoth Balloon’, as it was called, to 29,000 feet- the highest ever reached without oxygen, or a pressurised cabin.

Glaisher later helped to form a society to develop the science of aeronautics. In 1866, it became the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain. In 1868 the Crystal Palace was the venue for the first Aeronautical Exhibition.

Prints and text about George Grove, Arthur Sullivan and Thomas Attwood.

The text reads: From 1821 to 1834, Thomas Atwood - a pupil of Mozart and organist at St Paul’s Cathedral – lived in a villa on Beulah Hill, where he is now buried. He was 64 when, in 1829, he invited the young composer Mendlessohn to be his guest, after his tour of Scotland and Wales, which inspired the Hebrides Overture.

Two Mendlessohn pieces are dated Norwood, Surrey, November 1929. The Evening Bell is dedicated to Atwood and his daughter. The E. Minor Capriccio is his other ‘Norwood’ composition.

Mendlessohn made a return visit in 1832. He composed part of Son and a Stranger whilst here, and dedicated Three Preludes and Fugues for the Organ to Atwood, his friend and one of his earliest admirers.

The text reads: In 1852 George Grove became Secretary to the Crystal Palace. He came to live at Church Meadow, Sydenham, and devoted himself to music at the Palace. It was not long before the Saturday Concerts at Crystal Palace became a mecca for professional musicians and enthusiastic amateurs.

Arthur Sullivan met Grove just after his return from Leipzig as the first holder of the Mendlessohn scholarship. Grove arranged for the 19 year old’s first major composition, Tempest, to be performed on Saturday 5 April 1862. Sullivan became an overnight sensation. He was elevated into the highest musical circles, and there he met W.S. Gilbert.

Sullivan came to live in Sydenham, and Grove appointed him Professor of Pianoforte and Ballad Singing at the Crystal Palace School of Art.

Prints and text about CH Spurgeon.

The text reads: At the opening of the Crystal Palace in June 1854, a 21 year old Baptist Preacher, Charles Haddon Spurgeon, whose fiery sermons had already made him something of a celebrity, found himself seated next to an attractive female member of his congregation, Miss Susannah Thompson, with whom he was already on friendly terms.

Spurgeon handed her a book and pointed to a verse, “Seek a good wife of thy God, for she is the best gift of his providence”. After the ceremony they walked in the gardens. Susannah recalled, “from that time, our friendship grew apace, and quickly ripened into deepest love- a love which lives in my heart today”.

They married in 1856. The following year Spurgeon gave a sermon at the Crystal Palace, on behalf of the National Fund for sufferers from the Indian Mutiny, before a congregation of nearly 24,000, the largest assembly he had ever preached to.

In 1880 the Spurgeons bought Westwood, on Beulah Hill. Their new home was usually busy with tutors and students from Spurgeon’s college, who came to enjoy its splendid grounds, and hear their President discourse on any subject they cared to raise. Westwood was also the scene of Susannah’s many charitable activities. Westwood has been demolished since those days. The grounds were grassed over and became the playing fields of Westwood School.

In 1923 Spurgeon College, having outgrown its old premises in Newington, moved to a mansion at the top of South Norwood Hill, just a half a mile away from Spurgeon’s old home.

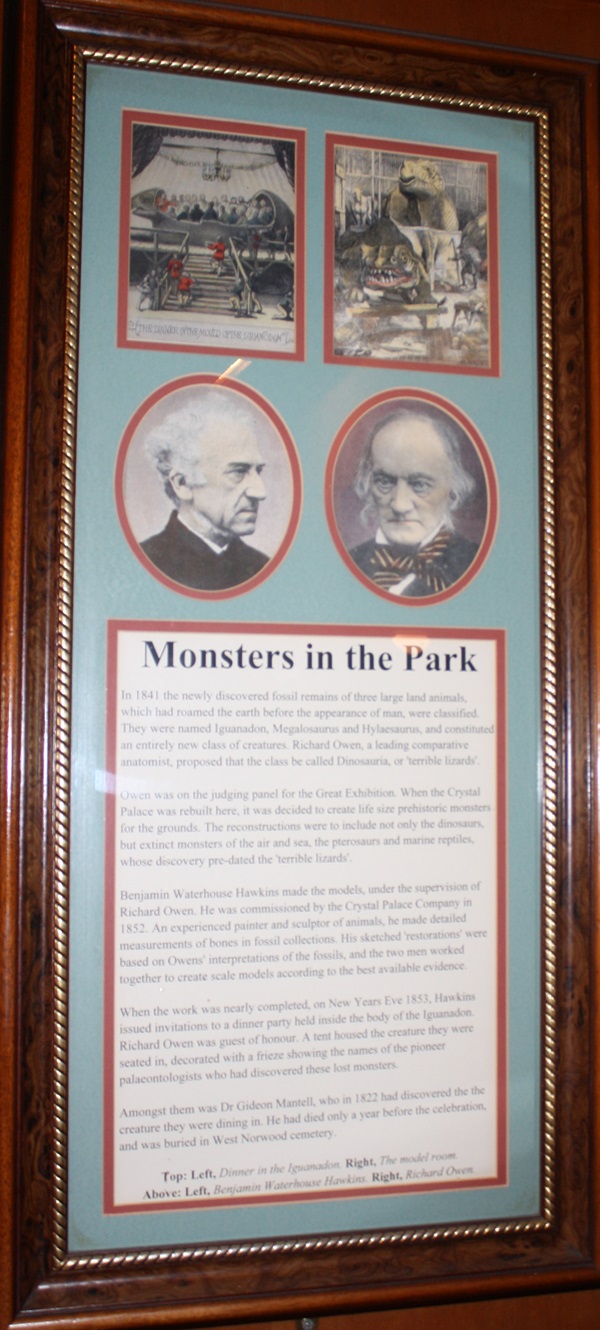

Prints and text about ‘monsters in the park’.

The text reads: In 1841 the newly discovered fossil remains of three large land animals, which had roamed the earth before the appearance of man, were classified. They were named Iguanadon, Megalosauraus and Hylaesaurus, and constituted an entirely new class of creatures. Richard Owen, a leading comparative anatomist, proposed that the class be called Dinosauria, or ‘terrible lizards’.

Owen was on the judging panel for the Great Exhibition. When the Crystal Palace was rebuilt here, it was decided to create like size prehistoric monsters for the grounds. The reconstructions were to include not only the dinosaurs, but extinct monsters of the air and sea, the pterosaurs and marine reptiles, whose discovery pre-dated the ‘terrible lizards’.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins made the models, under the supervision of Richard Owen. He was commissioned by the Crystal Palace Company in 1852. An experienced painter and sculptor of animals, he made detailed measurements of bones in fossil collection. His sketched ‘restorations’ were based on Owens’ interpretations of the fossils, and the two men worked together to create scale models according to the best available evidence.

When the work was nearly completed, on New Year’s Eve 1853, Hawkins issued invitations to a dinner party held inside the body of the Iguanodon. Richard Owen was guest of honour. A tent housed the creature they were seated in, decorated with a frieze showing the names of the pioneer palaeontologists who had discovered these lost monsters.

Amongst them was Dr Gideon Mantell, who in 1822 had discovered the creature they were dining in. He had died only a year before the celebration, and was buried in West Norwood cemetery.

Top: left, Dinner in the Iguanodon, right, The model room

Above: left, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, right, Richard Owen.

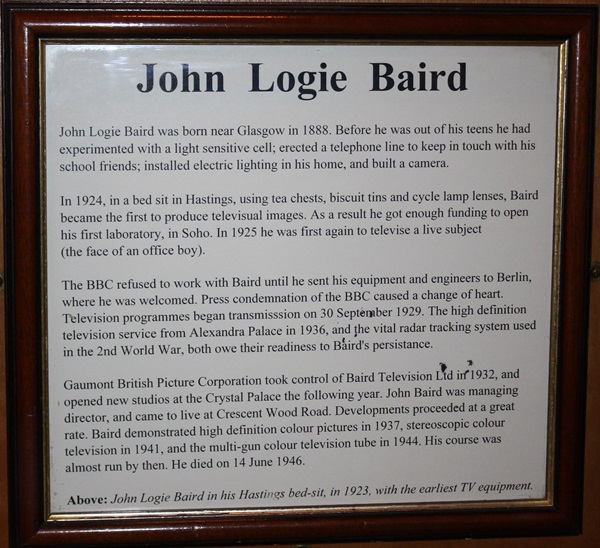

A print and text about John Logie Baird.

The text reads: John Logie Baird was born near Glasgow in 1888. Before he was out of his teens he had experimented with a light sensitive cell; erected a telephone line to keep in touch with his school friends; installed electric lighting in his home, and built a camera.

In 1924, in a bed sit in Hastings, using tea chests, biscuit tins and cycle lamp lenses, Baird became the first to produce televisual images. As a result he got enough funding to open his first laboratory, in Soho. In 1925 he was first again to televise a live subject (the face of an office boy).

The BBC refused to work with Baird until he sent his equipment and his engineers to Berlin, where he was welcomed. Press condemnation of the BBC caused a change of heart. Television programmes began transmission on 30 September 1929. The high definition television service from Alexandra Palace in 1936, and the vital radar tracking system used in the Second World War, both owe their readiness to Baird’s persistence.

Gaumont British Picture Corporation took control of Baird Television Ltd in 1932, and opened new studios at the Crystal Palace the following year. John Baird was managing director, and came to live at Crescent Wood Road. Developments proceeded at a great rate. Baird demonstrated high definition colour pictures in 1937, stereoscopic colour television in 1941, and the multi-gun colour television tube in 1944. His course was almost run by then. He died on 14 June 1946.

Above: John Logie Baird in his Hastings bed-sit, in 1923, with the earliest TV equipment.

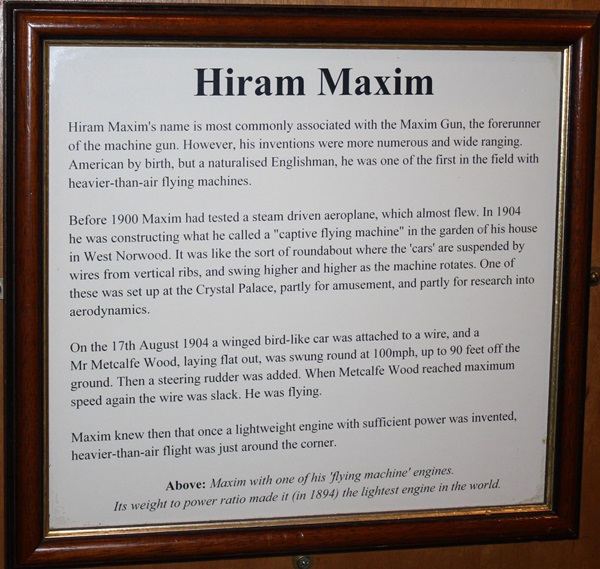

A print and text about Hiram Maxim.

The text reads: Hiram Maxim’s name is most commonly associated with the Maxim Gun, the forerunner of the machine gun. However, his inventions were more numerous and wide ranging. American by birth, but a naturalised Englishman, he was one of the first in the field with heavier-than-air flying machines.

Before 1900 Maxim had tested a steam driven aeroplane, which almost flew. In 1904 he was constructing what he called a “captive flying machine” in the garden of his house in West Norwood. It was like the sort of roundabout where the ‘cars’ are suspended by wires from vertical ribs, and swing higher and higher as the machine rotates. One of these was set up at the Crystal Palace, partly for amusement, and partly for research into aerodynamics.

On the 17 August 1904 a winged bird-like car was attached to a wire, and a Mr Metcalfe Wood, laying flat out, was swung round at 100mph, up to 90 feet off the ground. Then a steering rudder was added. When Metcalfe Wood reached maximum speed again the wire was slack. He was flying.

Maxim knew then that once a lightweight engine with sufficient power was invented, heavier-than-air flight was just around the corner.

Above: Maxim with one of his ‘flying machine’ engines. Its weight to power ratio made it (in 1894) the lightest engine in the world.

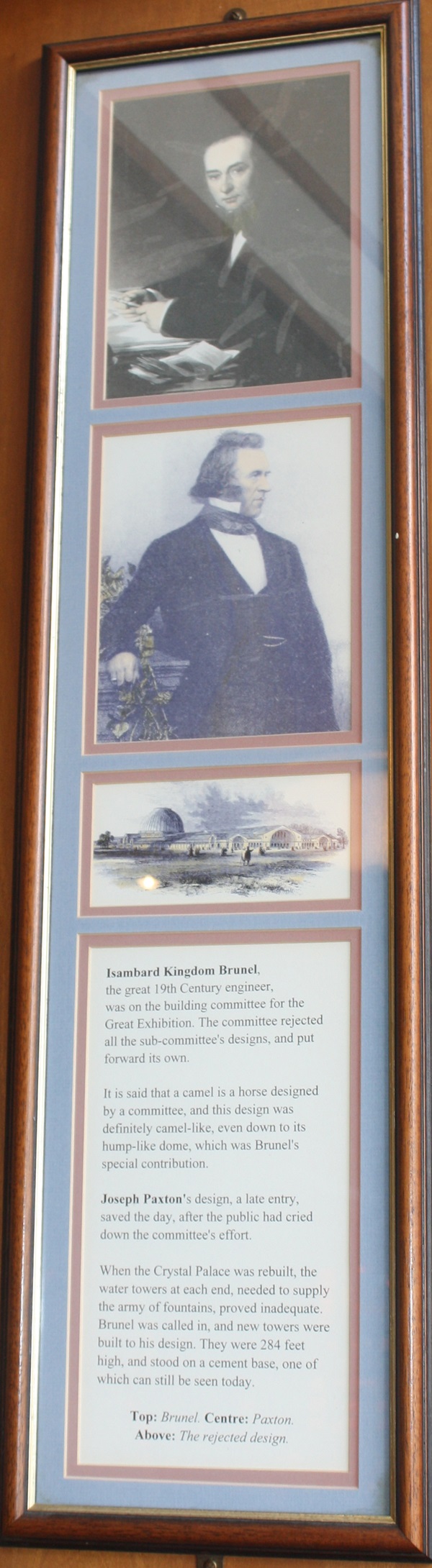

Prints and text about Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Joseph Paxton.

The text reads: Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the great 19th century engineer, was on the building committee for the Great Exhibition. The committee rejected all the sub-committee’s designs, and put forward its own.

It is said that a camel is a horse designed by a committee, and this design was definitely camel-like, even down to its hump-like dome, which was Brunel’s special contribution.

Joseph Paxton’s design, a late entry, saved the day, after the public had cried down the committee’s effort.

When the Crystal Palace was rebuilt, the water towers at each end, needed to supply the army of fountains, proved inadequate. Brunel was called in, and new towers rebuilt to his design. They were 284 feet high, and stood on a cement base, one of which can still be seen today.

Top: Brunel

Centre: Paxton

Above: The rejected design.

Text about how Gipsy Hill got its name.

The text reads: In the 1800s Norwood had a large population of gypsies. The enclosure of common land in the 19th century excluded the gypsies from their traditional camping grounds. They were harassed as vagrants, and forced to either give up their way of life or move out of the district.

The most famous of Norwood gypsies was Margret Finch. She was ‘Queen of Gypsies’ and died in 1740, aged 108 years. She lived near the lower end of Gypsy Hill in her later years, and habitually sat with her chin resting on her knees, smoking a pipe.

When she died her limbs were so fixed in position they could not straighten her out. So she was buried in her customary position, in a square coffin.

Large crowds attended her funeral, many of society’s elite whose fortunes she had told. The local politicians paid for the funeral, as her fortune telling fame had attracted custom the area.

A photograph of the Post Office, Westow Hill, Upper Norwood, c1910.

A photograph of Church Road, Upper Norwood, c1928.

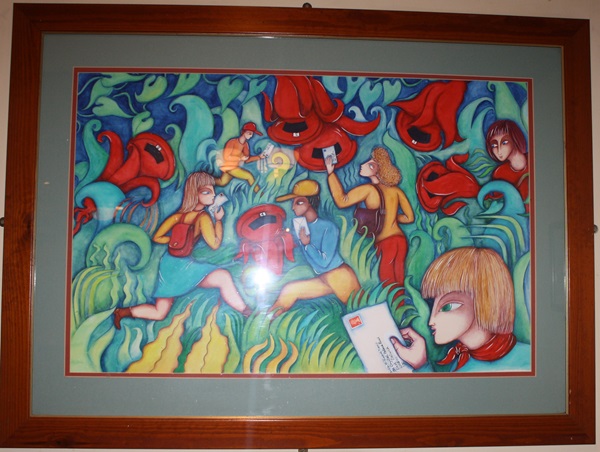

A watercolour painting entitled Looking For a Blooming Post Box, by Susan Hillwood-Harris.

Susan Hillwood-Harris is an illustrator. After graduating front Saint Martin’s School of Art she has worked mainly in editorial for magazines, newspapers and books.

Susan has lived in East Dulwich for over eight years. She is a keen gardener, and is currently trying to coax the jungle off the paper and into the suburban garden.

Her paintings for the Postal Order are all in watercolour.

J D Wetherspoon wish to thank The Crystal Palace Foundation for its help in providing the pictures and information used in the local history panels displayed in this pub.

The Crystal Palace Foundation is open Sundays, 11am-5pm at the Crystal Palace Museum, Annerley Road, SE19.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk