Named after The Sir John Oldcastle Tavern, which stood in the former grounds of Sir John’s nearby mansion, this was already long established by 1680. Oldcastle is thought to have been the model for Shakespeare’s character ‘Falstaff’.

Framed prints and text about Farringdon Road Station.

The text reads: Farringdon Road Station was the last stop on the Metropolitan Line that carried passengers from Paddington when it first opened in 1863. The Metropolitan was the first underground railway. The mainline station could not be built south of the new road, now the Marylebone Euston Road. The metropolitan was the first attempt to carry traffic on into the city, and to offer the working classes an easy way out.

The line emerged from the tunnel just north of Clerkenwell Green into a deep evacuation leading to Farringdon Station. During construction scaffolds were built across the excavation, supported by massive beams at 4pm on 18th June 1862 the fleet Sewer burst into the excavation. The beams were hurled into the air, great brickwork piers sixty feet high began to move, and the dark liquid began to roll towards the tunnel mouth.

Disaster was averted by diverting the black river through an old drain to run off into the Thames. After which the sewer was rebuilt.

Framed prints and text about Fulke Greville.

The text reads: Greville Street and Brooke Street both recall Fulke Greville.

He was born in1554 and went to school with Philip Sydney.

He followed Sydney to court and became one Queen Elizabeth 1’s favourites.

Greville remained in favour into the reign of her successor, King James 1, who enabled him Baron Brooke.

Brooke House at Holborn was Greville’s town residence. It was where he died in 1628 at the hand of an old servant, who murdered him when he discovered his master had left him with his will.

The house was demolished in 1676, and Brooke Street formed across its site. Greville Street, alongside this pub, was built across the gardens behind the house.

Top: Fulke Greville

Above: Sir Philip Sydney.

Framed prints and text about Turnmill Street.

The text reads: First known as ‘Turner Street’ due to the many mills in medieval times, mills for cotton spinning and grinding hair powder were still in operation here in the 1740’s.

Turnmill Street, nicknamed Turnbull, was in Elizabethan times and thereafter, a warden of alleys, choked with jerry-built inns and brothels, and dens full of thieves. Shakespeare’s Falstaff goes wrong in the Rose Tavern, which stood in Rose Alley in Turnmill Street.

The ‘liberation’ of vast amounts of land confiscated from the church at the Dissolution, and the influx of ready money obtained from ransacking the ‘New World’ and government sponsored piracy, or, as it was called, ’the wondrous enlargement of the suburbs’.

Turnmill Street became a byword.

“We have lived in continual Turnmill Street” says a character in Beaumont and Fletcher’s Scornfull Ladies.

To be called ‘a Turnbull whore’ was the worst insult that could be hurled at so-called ‘venereal virgins’. As the prostitutes were sarcastically called.

After 1660, an influx of French Protestant exiles (Huguenots) and Welsh, led to an altering of the local ‘ambiance’.

It had altered sufficiently by 1732 for John Wilkes, the radical politician, who was born locally, to rent a house in Turnmill Street. However, it was probably rented to house one of his mistresses.

Top: A Tudor ‘bilker’ (non-payer) is chased out by a cheated whore

Above: John Wilkes.

Framed drawings and text about the River Fleet.

The text reads: The river Fleet was called the Holeburne (the brook of the hollow) in the Middle Ages, except for the portion between Holborn Bridge and the Thames, which was called the Fleet, probably because the tide reached that far.

The Fleet’s source is at Highgate, the principal spring being behind Kenwood House. It was once fed by springs of the Clerks Well (from which Clerkenwell is named) and was called the River of Wells,

The ‘sweet waters’ became tainted early. There were complaints by both the Black and White Friars in 1290 that its smell overpowered their incense.

Up to around 1200 ships could come up as far as ‘Holeburne’ Bridge. But diverting water for mills, raising wharfs, and the filth produced by tanners and others, made it unnavigable.

An attempt to clean it and increase its flow failed to recreate its original breadth and depth, so it was referred to as a brook. The mills that sprang up along its banks led to its being called Turnmill Brook.

By the 1700s it was known as the Fleet Canal and was infamous. “The greatest good that I ever heard it did was to the undertaker, who is bound to acknowledge that he has found better fishing in that muddy stream than ever he did in clear water.”

London was divided into wards by the Saxons. These were administrative units, each under the control of an Alderman. The names of these wards became fixed by and large in the form we now have them around the end of the 13th century.

The ‘ward of Fafindon’ was named after W. Farindon, a Goldsmith, who purchased this Aldermanry in 1282. The ward remained in the same family for 82 years, and the name became established.

Farringdon Street was built above the course of the River Fleet, by then an underground sewer, in 1830.

Farringdon Road was built further up the Fleet valley, in the 1850s, also to cover over the malarial Fleet Slums “inhabited by many persons of a vicious and immoral character,” were cleared away to allow room for carriages to pass.

Framed prints and text about St John’s Gate.

The text reads: St Johns Gate was the main entrance to the Priory of St John’s. It was built in 1504 by the last Prior but one before Henry VIII confiscated church lands and closed down religious houses in what was known as The Dissolution.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, St Johns Gate, and what remained of the Priory buildings, was used as office of the Master of the Revels.

The first Master of the Revels was appointed in 1545. His job was to arrange masques (combination of music, dance and drama) and other entertainments at court.

However, by Elizabethan times he had become more of a censor, whose licence had to be obtained before a play was performed.

He also cut out bits or banned whole productions mainly on political grounds.

The Gate was for many years the home of Gentleman’s Magazine, founded in 1731 by its editor Edward Cave.

It was Cave who first employed Doctor Johnson when he arrived in London with his friend and pupil David Garrick.

Johnson contributed essays, poems, and reports of parliamentary debates. In reality these ‘reports’ were of Johnson’s own invention, but as they were so much better than the real thing no one seemed to mind.

Johnson himself, Garrick, who became the greatest actor-manager of his day, and Goldsmith the novelist, were regular visitors to Cave’s offices. The Gentleman’s Magazine lasted until 1914.

The Gate became a watch-house, a tavern, and an office for a masonic order. In 1874 the modern Order of St John re-acquired it as their headquarters.

Top: St John’s Gate

Above: Edward Cave.

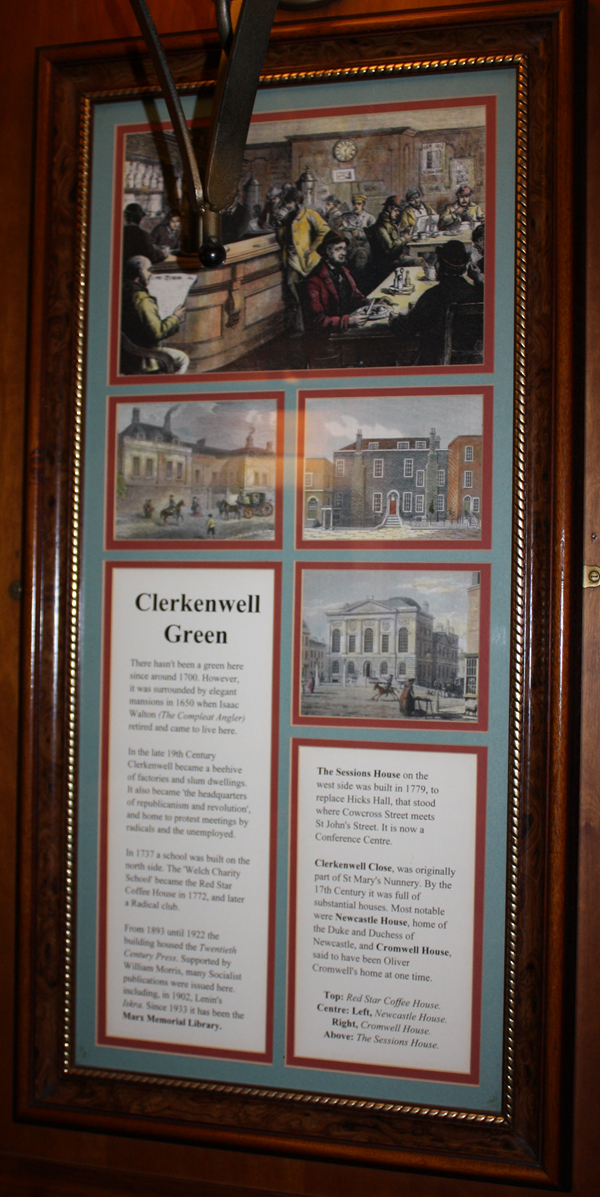

Framed prints and text about Clerkenwell Green.

The text reads: There hasn’t been a green here since around 1700. However, it was surrounded by elegant mansions in 1650 when Isaac Walton (the Complete Angler) retired and came to live here.

In the late 19th Century Clerkwell became a beehive of factories and slum dwellings. It also became ‘the headquarters of republicanism and revolution’, and home to protest meetings by radicals and the unemployed.

In 1737 a school was built on the north side. The ‘Welsh Charity School’ became the Red Star Coffee House in 1772, and later a Radical club.

From 1893 until 1922 the building housed the Twentieth Century Press. Supported by William Morris, many Socialist publications were issued here, including, in 1902, Lenin’s Iskra. Since 1933 it has been the Mars Memorial Library.

The Sessions House on the west side was built in 1779, to replace Hicks Hall, that stood where Cowcross Street meets St John’s Street. It is now a Conference Centre.

Clerkenwell Close, was originally part of St Mary’s Nunnery. By the 17th Century it was full of substantial houses. Most notable were Newcastle House, home of the Duke and Duchess of Newcastle, and Cromwell House, said to have been Oliver Cromwell’s home at one time.

Top: Red Star Coffee House

Centre: Left, Newcastle House

Right, Cromwell House

Above: The Sessions House.

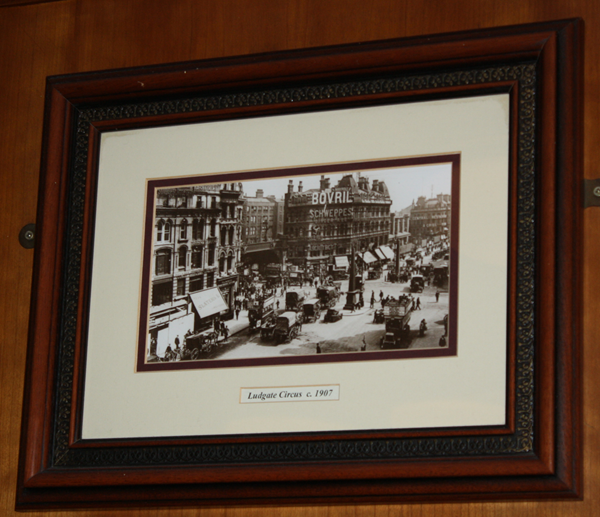

A framed photograph of Ludgate Circus c1907.

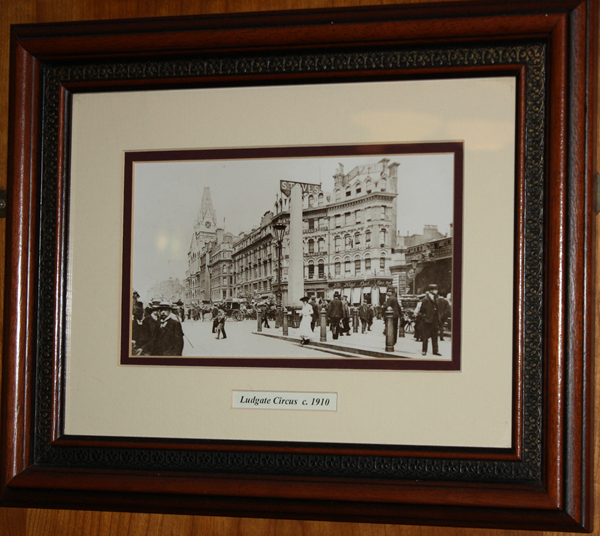

A framed photograph of Ludgate Circus c1910.

A framed photograph of parcel post at Mount Pleasant c1912.

A framed photograph of a parcel post delivery van c1920.

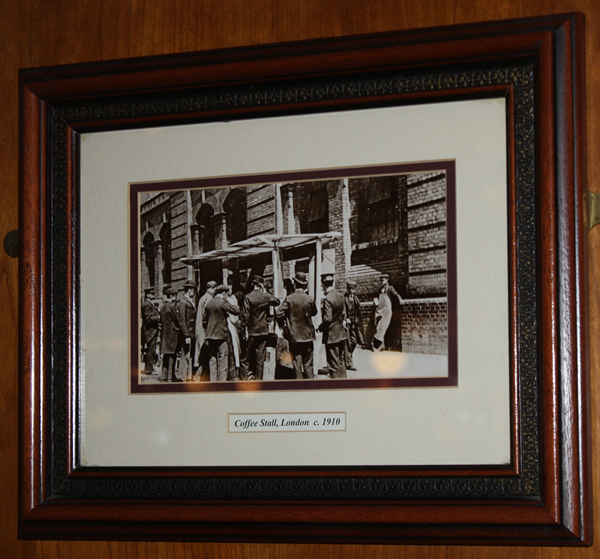

A framed photograph of a coffee stall, London c1910.

A framed photograph of Smithfield Market c1906.

A framed photograph of Smithfield Market c1910.

A framed photograph of Smithfield Market c1908.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk