402–408 Rayners Lane, Rayners Lane, London, HA5 5DY

Pinner is an outer London suburb which was originally a village. Its name is thought be of Saxon origin. Old records show that there was a church here during the 1230s. The annual village fair began in the early 1300s. On the north side of Pinner, there was woodland and a village green. The large fields to the south are now occupied by the housing estates which formed part of the area famously named ‘Metroland’, by Sir John Betjeman.

Prints and text about literary pros and cons.

The text reads: JB Priestly on the suburbs in 1927: “Where a desire for beauty wars with our common sympathy. A few more of these houses and this place will no longer charm the eye. A great many more of them and it will be hideous”. However he also noted “a number of people will have the chance of living decently and in comfort… people should come first … their chunks of happiness or misery are more important than certain delicate satisfactions of our own. We should be content to make the whole country hideous if we know for certain that by doing so we could also make all the people moderately happy”.

Osbert Lancaster wrote, “It is sad to reflect that so much ingenuity should have been wasted on streets and estates which will eventually become the slums of the future. That is, if a fearful and more sudden fate does not obliterate them prematurely, an eventuality that does much to reconcile to the prospects of aerial bombardment”. Which Betjeman reiterates:

Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough

It isn’t fit for humans now

Elsewhere Betjeman describes a stroll through suburbia: “Here the half-timbered villa holds its own boldly beside the bogus modern, here the bay window and stained glass front door survey the niggling rock garden and arid crazy paving.”

Of course towards the end of his life Betjeman discovered a nostalgia for the suburb which is captured in his poem Metro-Land. CFG Masterman in 1909 is ambivalent. He bemoans “miles and miles of little red boxes” yet “each boasts its pleasant drawing room, its bow window, its little front garden, its high sounding title Acacia Villa or Camper Down Lodge attesting unconquerable human aspiration”.

George Orwell in 1939 has no reservations. He complains “You know how these streets fester. As much alike as council houses … The stucco front, the creosoted gate, the privet hedge, the green front door … At perhaps one house in 50 some anti-social type who’ll probably end in the workhouse has painted his front door blue instead of green”. Orwell probably represents the full blown modern view of the suburb, at least amongst those who see fit to criticise it, but there has always been another side.

Charles Pooter in the 1890s, establishes the right note:

“After my work in the city I like to be at home. What’s the good of a home, if you are never in it. There is always something to be done: a tin tack here, a venetian blind to put straight, a fan to nail up or part of a carpet to nail down – all of which I can do with a pipe in my mouth”.

John Cadbury, who built the Bournville Garden Suburb, applauded the suburb for housing such large numbers of people so rapidly after the First World War, and for giving “a man his own house and garden, where he can feel that it is his own to do with as he wishes, and where at least he can have more than enough fresh air around him… a place where you can spend your evenings and free time profitably to yourself and others, without the need of going away for all your pleasures”.

Earnest Radford, in 1906, versified:

He leaned upon the narrow wall

That set the limit to his ground,

And marvelled, thinking of it all,

That he such happiness had found.

He had no word for it but bliss;

He smoked his pipe; he thanked his stars;

And, what more wonderful than this?

He blessed the groaning, stinking cars

That made it doubly sweet to win

The respite of the hours apart

From all the broil and sin and din

Of London's damned money-mart”.

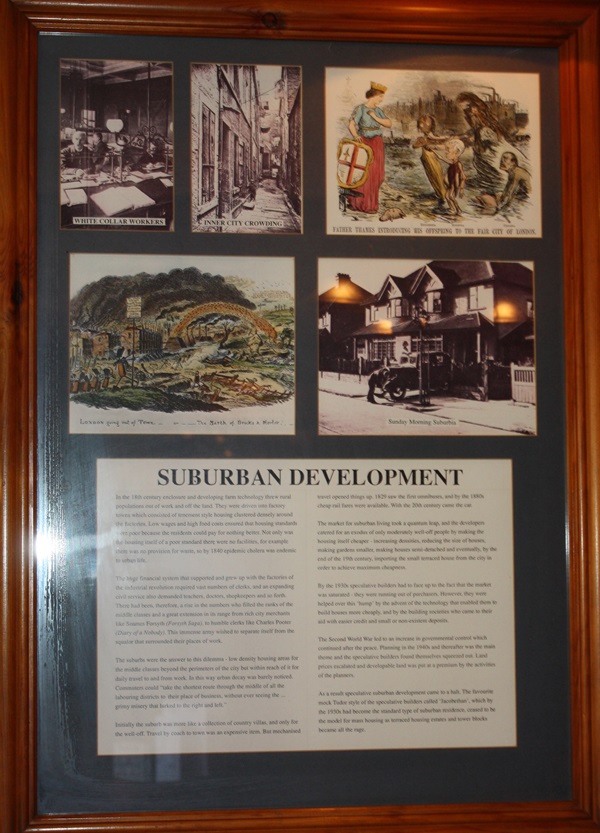

Photographs, illustrations and text about suburban development.

The text reads: In the 18th century enclosure and developing farm technology threw rural populations out of work and off the land. They were driven into factory towns which consisted of tenement style housing clustered densely around the factories. Low wages and high food costs ensured that housing standards were poor because the residents could pay for nothing better. Not only was the housing itself of a poor standard there were no facilities, for example there was no provision for waste, so by 1840 epidemic cholera was endemic to urban life.

The huge financial system that supported and grew up with the factories of the Industrial Revolution required vast numbers of clerks, and an expanding civil service also demanded teachers, doctors, shopkeepers and so forth. There had been, therefore, a rise in the numbers who filled the ranks of the middles classes and a great extension in its range from rich city merchants like Soames Forsyth (Forsyth Saga) to humble clerks like Charles Pooter (Diary of a Nobody). This immense army wished to separate itself from the squalor that surrounded their places of work.

The suburbs were the answer to this dilemma – low density housing areas for the middle classes beyond the perimeters of the city but within reach of it for daily travel to and from work. In this way urban decay was barely noticed. Commuters could “take the shortest route through the middle of all the labouring districts to their place of business, without ever seeing the … grimy misery that lurked to the right and left”.

Initially the suburb was more like a collection of country villas, and only for the well-off. Travel by coach to town was an expensive item. But mechanised travel opened things up. 1829 saw the first omnibuses, and by the 1880s cheap rail fares were available. With the 20th century came the car.

The market for suburban living took a quantum leap, and the developers catered for an exodus of only moderately well-off people by making the housing itself cheaper – increasing densities, reducing the size of houses, making gardens smaller, making houses semi-detached and eventually, by the end of the 19th century, importing the small terraced house from the city in order to achieve maximum cheapness.

By the 1930s speculative builders had to face up to the fact that the market was saturated – they were running out of purchasers. However, they were helped over this hump by the advent of the technology that enabled them to build houses more cheaply, and by the building societies who came to their aid with easier credit and small or non-existent deposits.

The Second World War led to an increase in governmental control which continued after the peace. Planning in the 1940s and thereafter was the main theme and the speculative builders found themselves squeezed out. Land prices escalated and developable land was pit at a premium by the activities of the planners.

As a result speculative suburban development came to a halt. The favourite mock Tudor style of the speculative builders called Jacobethan, which by the 1930s had become the standard type of suburban residence, ceased to be the model for mass housing as terraced housing estates and tower blocks became all the rage.

Photographs, illustrations and text about the arts and craft movement.

The text reads: The suburb of 1840 remained terraced based which was essentially an urban style whether used spaciously for the rich or cramped up divided only by narrow alleys in tenements for the poor. But by the 1870s the garden city movement, and housing estates like Port Sunlight and Bournville, plus new country houses designed by arts and craft architects were all playing their part in changing the face of domestic house design.

In 1861 the style of Gothic revival was in full spate. William Morris and Phillip Webb wanted to introduce a fresh approach. They looked for inspiration not to great public buildings but to ordinary traditionally built English houses, what they called the vernacular architecture. The Red House was the result – designed by Webb for Morris. It is the prototype of modern suburban building, leaving the Victorian Gothic/Italianate amalgam behind as well as the austere Georgian terraced style.

The innovation of the Red House was taken up by Norman Shaw who was acquainted with Morris’ circle but not a member of it, and popularised in the so called Queen Anne style. This is a misleading name. Shaw and his accomplice and friend WE Nesfield, gathered the features of their designs by touring Kent and Sussex and sketching the buildings they found there. The irregular Victorian free style that emerged made use of several features they discovered in the English villages. The result was a large step towards dispersing the gloom and heaviness of the earlier Victorian style and to let in what Mathew Arnold called “sweetness and light”.

Bedford Park was the first major fruit of their endeavours, translating the ideas of the Red House into a formula that could be used for suburban housing on a large scale. Bedford Park became the “hallmark of the garden city movement” and a guide for the architecture of most of twentieth century suburbia.

After Shaw came, arguably the greatest of the architects who took up the ideas of the Red House, CFA. Voysey (1857-1941). His simple designs of large detached houses provided the archetype for most of the types of suburban semi that we are so familiar with. He simplifies the arts and craft building still further from Shaw’s Queen Anne style, producing buildings that are all of a piece, without any fussiness or muddle of components, and with thought having been given at all points to the setting of the building and the use and lighting of the interior space. By the time we enter the twentieth century and the suburban development boom the type of architecture, though derived from the formulations of the arts and crafts movement, is nevertheless something of a rogue beast, driven neither by the artistic aspirations of the Edwardian, nor the philanthropic public spirit of the Victorians nor even by the avante garde modernist ideology of the architects who clustered around Le Corbusier.

It is “a quick fix” style produced by speculative builders with an overriding need to “get on with it” and get it solved. These men who started companies like Laings and Wates, had a sharp appreciation of what their customers would like and what they would buy. They established a style and were therefore the butt of the architect’s displeasure.

The nearest that modern architects or architecture got to the suburb was an adaptation of the “modernist international style” that was called the suntrap house. Very few pure international style estates were ever built and they are now a great rarity.

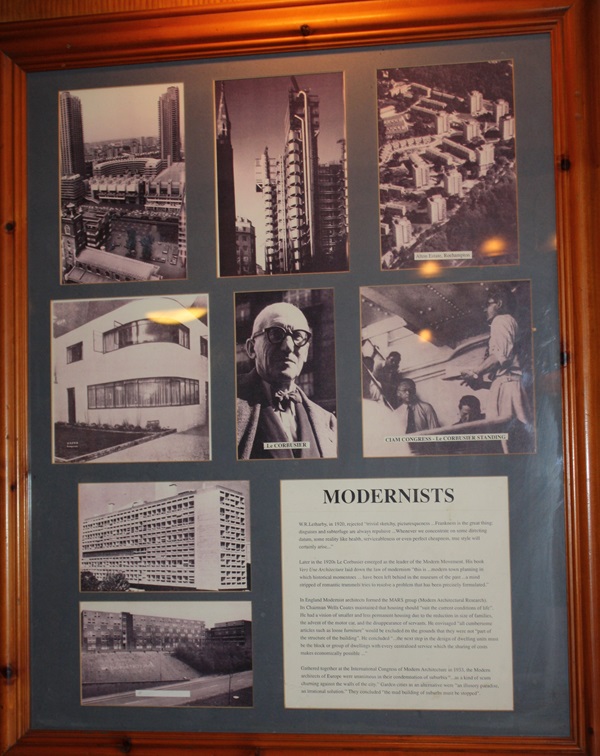

Photographs and text about modernists.

The text reads: WR Letharby, in 1920, rejected “trivial sketchy, picturesqueness … Frankness is the greatest thing: disguises and subterfuge are always repulsive … Whenever we concentrate on some directing datum, some reality like health, serviceableness or even perfect cheapness, true style will certainly arise…”.

Later in the 1920s Le Corbusier emerged as the leader of the Modern Movement. His book Vers Une Architecture laid down the law of modernism “this is … modern town planning in which historical mementoes … have been left behind in the museum of the past … a mind stripped of romantic trammels tries to resolve a problem that has been precisely formulated”.

In England, modernist architects formed the MARS group (Modern Architectural Research). Its chairman Wells Coates maintained that housing should “suit the current conditions of life”. He had a vision of smaller and less permanent housing due to the reduction in size of families, the advent of the motor car, and the disappearance of servants. He envisaged “all cumbersome articles such as loose furniture” would be excluded on the grounds that they were not “part of the structure of the building”. He concluded “… the next step in the design of dwelling units must be the block or group of dwellings with every centralised service which the sharing of costs makes economically possible…”

Gathered together at the International Congress of Modern Architecture in 1933, the modern architects of Europe were unanimous in their condemnation of suburbia “…as a kind of scum churning against the walls of the city”. Garden cities as an alternative were “an illusory paradise, an irrational solution.” They concluded “the mad building of suburbs must be stopped”.

Illustrations and text about Bedford Park.

The text reads: In 1877 Jonathan Carr decided to plan an estate in London. The outcome, which included a church, a pub, and a shopping area, was in fact an urban village, and involved a pioneering style of detached medium sized housing.

It was made more communal by being publicised as a retreat for aesthetes. There was no attempt to make it socially integrated in the sense that the later Hampstead Garden Suburb was to be. It was in fact a rare and unique item offering an environment suitable for the intelligentsia where the rude vulgarities of the rest of London would not intrude. However unique this particular development the idea of village retreat close to the centre of town was to prove an enormously influential one.

Norman Shaw was the main provider of designs for houses and the layout, and his unfussy and gently proportioned buildings were a revelation of calm when seen against the established heavily detailed Gothic housing of the day. The style that Shaw established at Bedford Park, known as the Queen Anne Style, was the forerunner to all the suburban styles that followed.

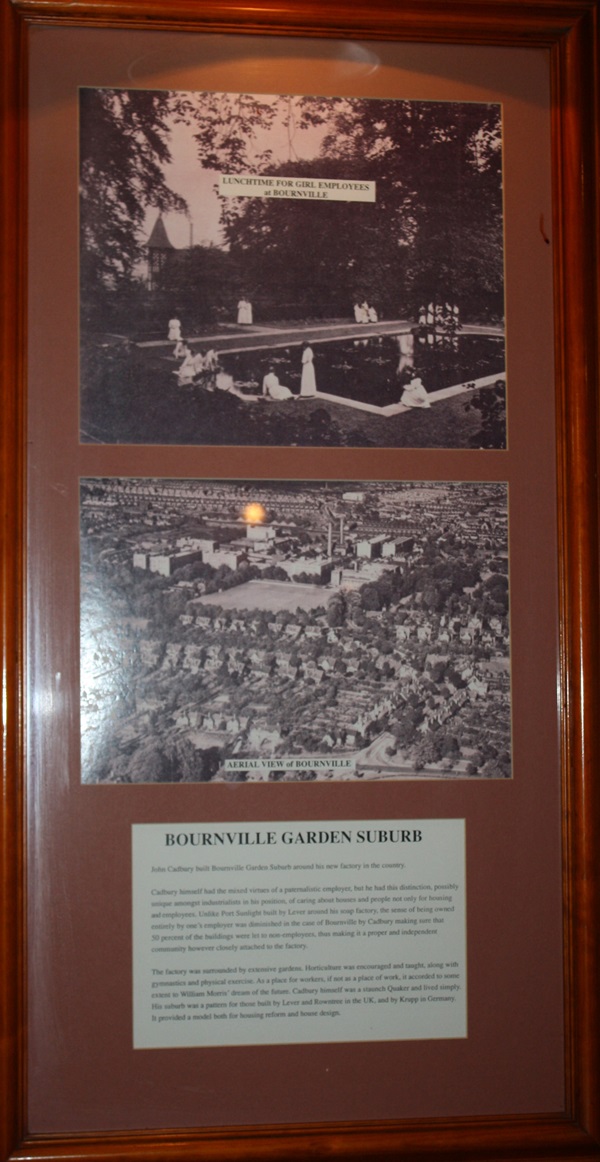

Photographs and text about Bournville garden Suburb.

The text reads: John Cadbury built Bournville Garden Suburb around his new factory in the country.

Cadbury himself had the mixed virtues of a paternalistic employer, but he had this distinction, possibly unique amongst industrialists in his position, of caring about houses and people not only for housing and employees. Unlike Port Sunlight built by the Lever around his soap factory, the sense of being owned entirely by ones employer was diminished in the case of Bournville by Cadbury making sure that 50 percent of the buildings were let to non-employees, thus making it a proper and independent community however closely attached to the factory.

The factory was surrounded by extensive gardens. Horticulture was encouraged and taught along with gymnastics and physical exercise. As a place for workers, if not as a place of work, it accorded to some extend to William Morris’ dream of the future. Cadbury himself was a staunch Quaker and lived simply. His suburb was a pattern for those built by Lever and Rowntree in the UK, and by Krupp in Germany. It provided a model both for housing reform and house design.

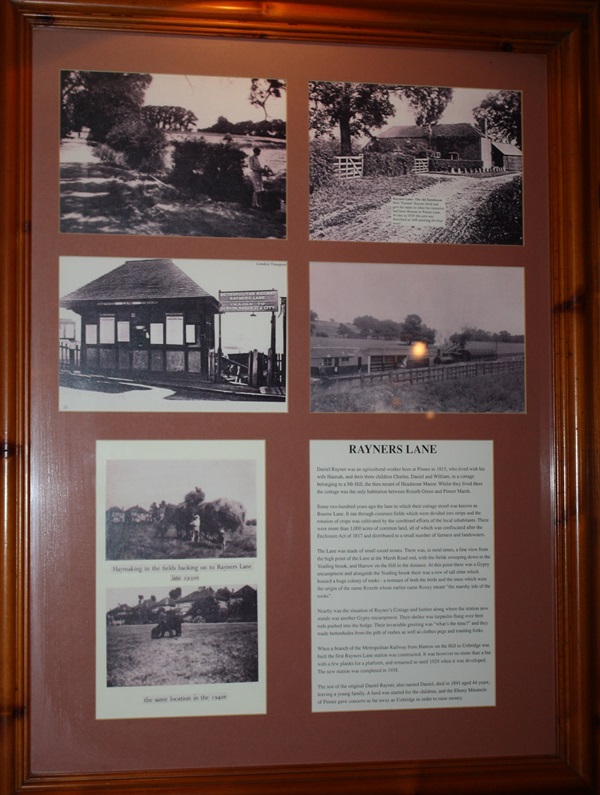

Photographs and text about Rayners Lane.

The text reads: Daniel Rayner was an agricultural worker born at Pinner in 1815, who lived with his wife Hannah, and their three children Charles, Daniel and William, in a cottage belonging to a Mr Hill, the then tenant of Headstone Manor. Whilst they lived there the cottage was the only habitation between Roxeth Green and Pinner Marsh.

Some two hundred years ago the lane in which their cottage stood was known as Bourne Lane. It ran through common fields which were divided into strips and the rotation of crops was cultivated by the combined efforts of the local inhabitants. There were more than 1,000 acres of common land, all of which was confiscated after the Enclosure Act of 1817 and distributed to a small number of farmers and landowners.

The Lane was made of small round stones. There was, in rural times, a fine view from the high point of the Lane at the Marsh Road end, with the fields sweeping down to the Yeading brook, and Harrow on the Hill in the distance. At this point there was a Gypsy encampment and alongside the Yeading brook there was a row of tall elms which housed a huge colony of rooks – a remnant of both the birds and the trees which were the origin of the name Roxeth whose earlier name Roxey meant “the marshy isle of the rooks”.

Nearby was the situation of Rayners Cottage and further along were the station now stands was another Gypsy encampment. Their shelter was a tarpaulin flung over bent rods pushing into the hedge. Their invariable greeting was “what’s the time?” and they made buttonholes from the pith of rushes as well as clothes pegs and toasting forks.

When a branch of the Metropolitan Railway from Harrow on the Hill to Uxbridge was built the first Rayners Lane station was constructed. It was however no more than a hut with a few planks for a platform, and remained so until 1929 when it was developed. The new station was completed in 1938.

The son of the original Daniel Rayner, also named Daniel, died in 1891 aged 44 years, leaving a young family. A fund was started for the children, and the Ebony Minstrels of Pinner gave concerts as far away as Uxbridge in order to raise money.

Photographs of Rayners Lane junction of Suffolk Road, and Whittington Avenue looking north, c1931.

A photograph of Rayners Lane.

A collection of old photographs of Rayners Lane.

A photograph of Mr Rayner’s farm house, c1920.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk