This pub is named after the 18th-century lord of the manor who began the development of Middleton.

Text about The Harbord Harbord.

The text reads: Saxon in origin, Middleton owes its name to the de Middleton family, local landowners in the 12th century. They were succeeded as Lords of the Manor by the de Bartons and the Asshetons, whose vast Middleton and Thornham Estates were occupied largely by tenant farmers.

The first Sir Ralph Assheton became vice constable of England on the strength of his outstanding bravery in the Wars of the Roses. His grandson, Richard, was knighted on Flodden Field in 1513, for his heroism in leading the Middleton Archers in battle.

Born in 1605, Ralph Assheton achieved fame during the Civil War, for masterminding the defeat of the Royalist forces at Manchester in 1642. But although the Assheton family gained national recognition while they held the manor, from 1438 to 1765, Middleton retained its village character. Firmly opposed to expansion, the widow of the last Sir Ralph pledged to keep it ‘uncontaminated by vulgar workshops’.

Only when Harbord Harbord (later Lord Suffield) succeeded as Lord of the Manor by marriage in 1765 was land leased for development. The first leases were granted in 1776, along the turnpike now known as Long Street. The Enterprising Harbord Harbord also obtained a Market Charter in 1791. It is his name which is recalled in the pub that you are now in.

Prints, illustrations and text about the Harbord Legacy.

The text reads: Harbord Harbord, first Baron Suffield, married Mary Assheton of Middleton, the daughter and co-heiress of Sir Ralph Assheton, on 7 October 1760. The Assheton family were Lords of the Manor, and Mary’s ancestor, Sir Ralph, is commemorated in the Flodden window in St Leonard’s Church, which dates back to the mid 1500s.

Harbord Harbord has been described as the “last truly active Lord of the Manor of Middleton” who “achieved a lot for the town during the years of the Industrial Revolution when Middleton… (grew)… from village to town status”. Lord Suffield obtained a Royal Charter from King George III in 1791 to hold a weekly market and annual fairs. He then built a market house and warehouses at his own expense. He died in 1810. Mary died in London in 1823.

Edward, Harbord and Mary’s second son, became 3rd Baron Suffield, succeeding his brother William in 1821. He was a British radical politician, anti-slavery campaigner and prison reformer. He outrages his family by declaring himself a Liberal at a public meeting held to petition for an inquiry into the Peterloo Massacre. He was active in the House of Lords for the Whigs, especially in advocating for the abolition of the slave trade.

Charles Harbord, 5th Baron Suffield, was Edward’s son, and succeeded to the title when his half-brother died childless in 1853. A Liberal politician, like his father, he was a close friend of Edward VII. He was chief of staff to the Prince of Wales during the Prince’s expedition to India in 1875-76, and served in two of Gladstone’s administrations. When the Prince of Wales became King in 1901, Suffield was made a Lord-in-Waiting-in-Ordinary to the King.

Above: Charles Harbord, 5th Baron Suffield

Right: Edward Harbord, 3rd Baron Suffield

Far right: above, the cover of Mary Assheton’s commonplace (scrap) book, The Temple of Love, below, Edward Vernon, 4th Lord Suffield.

A print and text about Long Street.

The text reads: The site of The Harbord Harbord is a particularly old row of shops in Middleton, probably dating from the 1860s.

Around the turn of the 19th century this building was occupied by Crooks. Many people will remember it as Burton’s menswear store in the 1950s. This was before it was expanded into next door and the frontage revamped to form four windows. At that time there was a snooker hall upstairs. It was Woolworth’s who expanded and revamped the site to the size it is today. Woolworth’s occupied the site from the late 1950s and throughout most of the 1960s.

Woolworth’s closed in around 1971 and the site became Cee & Cee and then Gainmore (both supermarkets), and then Kwiksave in the 1980s. It was later home to a gallery and picture framing outlet and a women’s clothes shop called Neighbours, before being transformed into this Wetherspoon free house.

Photographs of the site of The Harbord Harbord.

Top: This row of shops, c1935

Left: A view of this site when it was Crooks’, c1910.

Above: This site when it was a Burton store, c1953.

A print and text about Samuel Bamford.

The text reads: Samuel Bamford was born in Middleton on 28 February 1788. He was a weaver by trade but took a keen interest in poetry and reading, particularly the works of parliamentary reformers and radicals. His radical political views led him to form the Middleton branch of The Hampden Reform Club, to campaign for repeal of the corn laws and electrical reform.

On August 16 1819, Sam led a large group of Middleton people to St Peters Fields in Manchester to attend a reform meeting. The Manchester Yeomanry were ordered to attack the crowd and a bloody massacre took place, leaving 11 dead and around 500 injured, including women and children.

For his part, Sam was jailed for a year. He subsequently kept writing for the cause and became correspondent for a London newspaper. He died aged 84 on April 13 1872 and is buried in the St Leonard’s Parish Church cemetery.

Illustrations and text about the Peterloo Massacre.

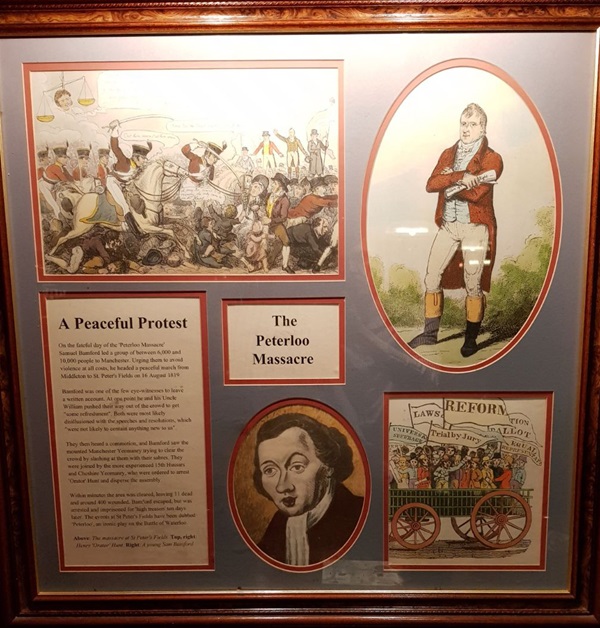

The text reads: On the fateful day of the Peterloo Massacre, Samuel Bamford led a group of between 6,000 and 10,000 people to Manchester. Urging them to avoid violence at all coasts, he headed a peaceful march from Middleton to St Peter’s Fields on 16 August 1819.

Bamford was one of the few eye-witnesses to leave a written account. At one point he and his uncle William pushed their way out of the crowd to get “some refreshment”. Both were most likely disillusioned with the speeches and resolutions, which “were not likely to contain anything new to us”.

They then heard a commotion, and Bamford saw the mounted Manchester Yeomanry trying to clear the crowd by slashing at them with their sabres. They were joined by the more experienced 15th Hussars and Cheshire Yeomanry, who were ordered to arrest ‘Orator’ Hunt and disperse the assembly.

Within minutes the area was cleared, leaving 11 dead and around 400 wounded. Bamford escaped, but was arrested and imprisoned for high treason ten days later. The events at St Peter’s Fields have been dubbed ‘Peterloo’, an ironic play on the Battle of Waterloo.

Above: The massacre at St Peter’s Fields

Top, right: Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt

Right: A young Sam Bamford.

A print and text about Thomas Langley.

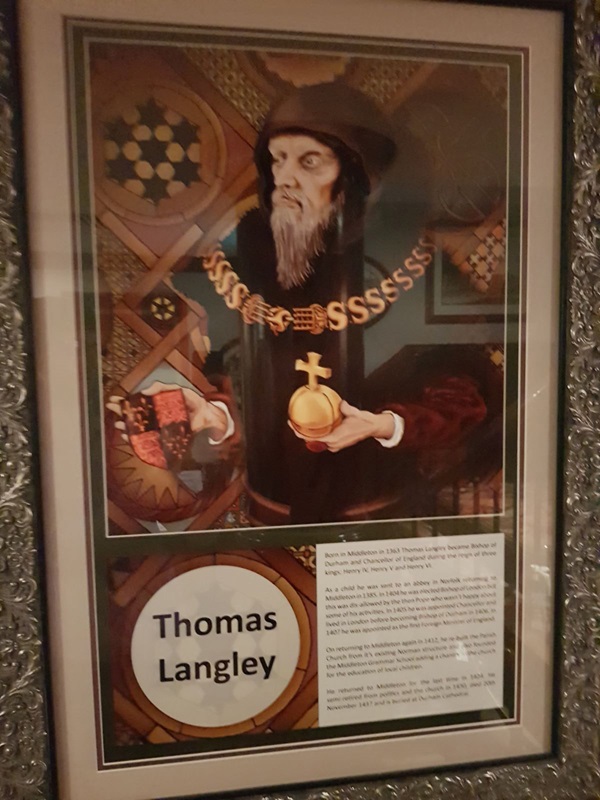

The text reads: Born in Middleton in 1363 Thomas Langley became Bishop of Durham and chancellor of England during the reign of three kings; Henry IV, Henry V and Henry VI.

As a child he was sent to an abbey in Norfolk, returning to Middleton in 1385. In 1404 he was elected Bishop of London but this was dis-allowed by the then Pope who wasn’t happy about some of his activities. In 1405 he was appointed chancellor and lived in London before becoming Bishop of Durham in 1406. In 1407 he was appointed as the first foreign minister of England.

On returning to Middleton again in 1412, he re-built the parish church from its existing Norman structure and also founded the Middleton Grammar School adding a chantry to the church for the education of local children.

He returned to Middleton for the last time in 1424. He semi-retired from politics and the church in 1430, died 20 November 1437 and is buried at Durham Cathedral.

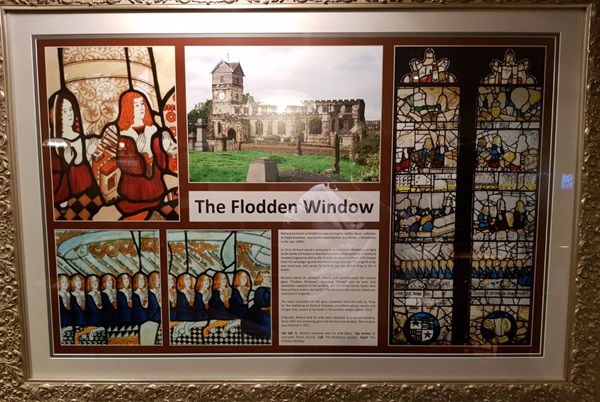

Photographs and text about the Flodden Window.

The text reads: Richard Assheton of Middleton was an English soldier. His grandfather, Sir Ralph Assheton, married Margret Barton, the heiress of Middleton, in the late 1400s.

In 1513, Richard raised a company of archers from Middleton to fight at the Battle of Flodden in Northumberland, when James IV of Scotland invaded England to aid his ally, France, by diverting Henry VIII’s troops from his campaign against the French King Louis XII. The English army was victorious, and James IV became the last British King to die in battle.

Richard rebuilt St Leonard’s Church and commissioned the stained-glass Flodden Windows, depicting “himself and his wife, and seventeen captains of the archers, and the priest Henry Taylor who blessed them before the battle”. The window is the second oldest war memorial in England.

The main inscription on the glass translates from the Latin as “Pray for the wellbeing of Richard Assheton and those whose names and images they caused to be made in the window shown above, 1515”.

Originally Richard and his wife were depicted in a second window. Since 1847 the remaining glass has formed one window. The window was restored in 2012.

Top left: Sir Richard Assheton and his wife Mary

Top centre: St Leonard’s Parish Church

Left: The Middleton archers

Right: The Flodden Window.

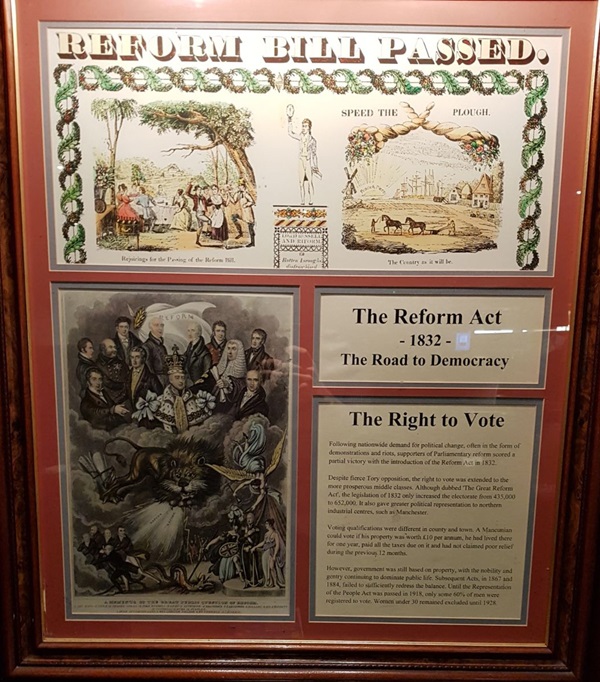

Illustrations and text about the Reform Act.

The text reads: Following nationwide demand for political change, often in the form of demonstrations and riots, supporters of parliamentary reform scored a partial victory with the introduction of the Reform Act in 1832.

Despite fierce Tory opposition, the right to vote was extended to the more prosperous middle classes. Although dubbed ‘The Great Reform Act’, the legislation of 1832 only increased the electorate from 435,000 to 652,000. It also gave greater political representation to northern industrial centres, such as Manchester.

Voting qualifications were different in county and town. A Mancunian could vote if his property was worth £10 per annum, he had lived there for one year, paid all the taxes due on it and had not claimed poor relief during the previous 12 months.

However, government was still based on property, with the nobility and gentry continuing to dominate public life. Subsequent Acts, in 1867 and 1884, failed to sufficiently redress the balance. Until the Representation of the People Act was passed in 1918, only some 60% of men were registered to vote. Women under 30 remained excluded until 1928.

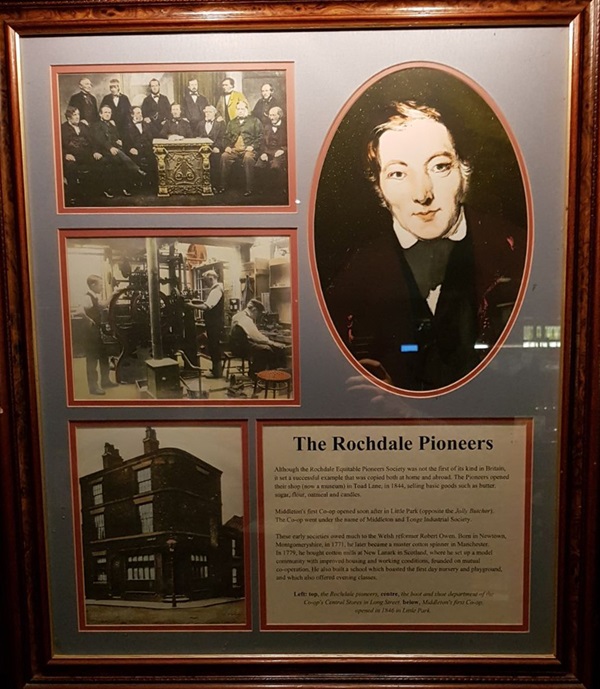

Prints and text about the Rochdale Pioneers.

The text reads: Although the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society was not the first of its kind in Britain, it set a successful example that was copied both at home and abroad. The Pioneers opened their shop (now a museum) in Toad Lane, in 1844, selling basic goods such as butter, sugar, flour, oatmeal and candles.

Middleton’s first Co-op opened soon after in Little Park (opposite the Jolly Butcher). The Co-op went under the name of Middleton and Tonge Industrial Society.

These early societies owed much to the Welsh reformer Robert Owen. Born in Newtown, Montgomeryshire, in 1771, he later became a master cotton spinner in Manchester. In 1779, he bought cotton mills at New Lanark in Scotland, where he set up a model community with improved housing and working conditions, founded on mutual co-operation. He also built a school which boasted the first day nursery and playground, and which also offered evening classes.

Left: top, the Rochdale Pioneers, centre, the boot and shoe department of the Co-op’s Central Stores in Long Street, below, Middleton’s first Co-op, opened in 1846 in Little Park.

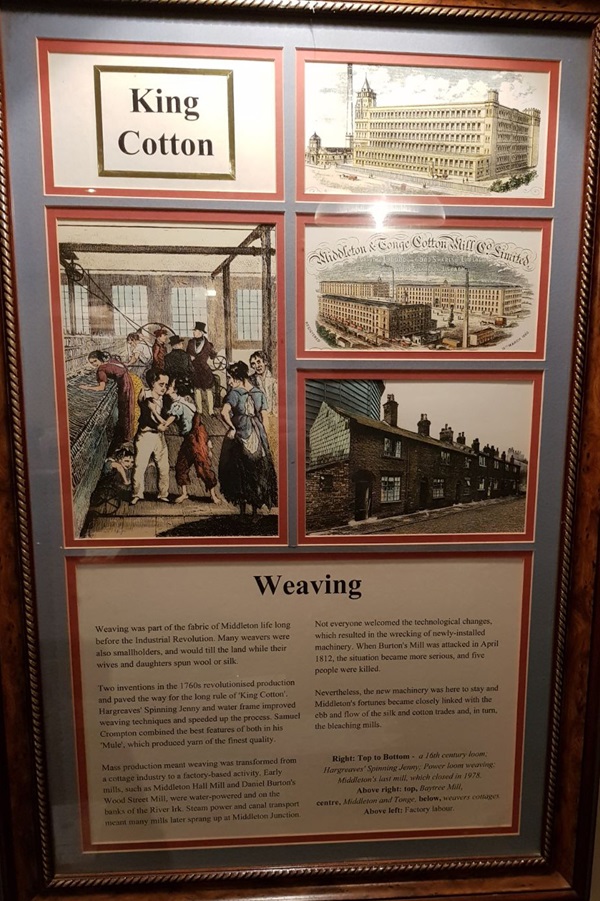

Illustrations and text about the weaving industry.

The text reads: Weaving was part of the fabric of Middleton life long before the Industrial Revolution. Many weavers were also smallholders, and would till the land while their wives and daughters spun wool or silk.

Two inventions in the 1760s revolutionised production and paved the way for the long rule of ‘King Cotton’. Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny and water frame improved weaving techniques and speeded up the process. Samuel Crompton combined the best features of both his ‘Mule’, which produced yarn of the finest quality.

Mass production meant weaving was transformed from a cottage industry to a factory based activity. Early mills, such as Middleton Hall Mill and Daniel Burton’s Wood Street Mill, were water-powered and on the banks of the River Irk. Steam power and canal transport meant many mills later sprang up at Middleton Junction.

Not everyone welcomed the technological changes, which resulted in the wrecking of newly-installed machinery. When Burton’s Mill was attacked in April 1812, the situation became more serious, and five people were killed.

Nevertheless, the new machinery was here to stay and Middleton’s fortunes became closely linked with the ebb and flow of the silk and cotton trades and, in turn, the bleaching mills.

Right: top to bottom – a 16th century loom: Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny: power look weaving: Middleton’s last mill which closed in 1978

Above right: top, Baytree Mill, centre, Middleton and Tonge, below, weavers cottages

Above left: Factory labour.

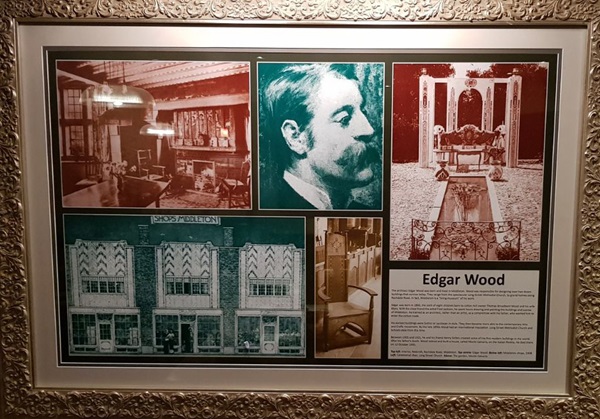

Photographs, an illustration and text about Edgar Wood.

The text reads: The architect Edgar Wood was born and lived in Middleton. Wood was responsible for designing over two dozen buildings that survive today. They range from the spectacular Long Street Methodist Church, to grand homes along Rochdale Road. In fact, Middleton is a living museum of his work.

Edgar was born in 1860, the sixth of eight children born to cotton mill owner Thomas Broadbent Wood and his wife Mary. With his close friend the artist Fred Jackson, he spent hours drawing and painting the buildings and scenes of Middleton. He trained as an architect, rather than an artist, as a compromise with his father, who wanted him to enter the cotton trade.

His earliest buildings were Gothic or Jacobean in style. They then became more akin to the contemporary Arts and Crafts movement. By the late 1890s Wood had an international reputation. Long Street Methodist Church and School date from this time.

Between 1905 and 1921, he and his friends Henry Sellars created some of the first modern buildings in the world. After his father’s death, Wood retired and built a house, called Monte Calvario, on the Italian Riviera. He died there on 12 October 1935.

Top left: Interior, Redcroft, Rochdale Road, Middleton

Top centre: Edgar Wood

Below left: Middleton shops, 1908

Left: Ceremonial chair, Long Street Church

Above: The garden, Monte Calvario.

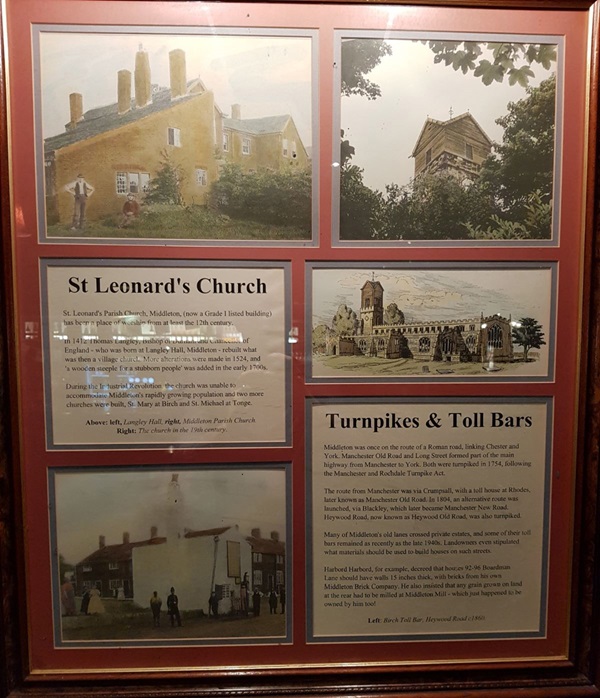

Illustrations, prints and text about St Leonard’s Church and local turnpikes.

The text reads: St Leonard’s Church

St Leonard’s Parish Church, Middleton, (now a grade I listed building) has been a place of worship from at least the 12th century.

In 1412 Thomas Langley, Bishop of Durham and chancellor of England – who was born at Langley Hall, Middleton – rebuilt what was then a village church. More alterations were made in 1524, and ‘a wooden steeple for a stubborn people’ was added in the early 1700s.

During the Industrial Revolution, the church was unable to accommodate Middleton’s rapidly growing population and two more churches were built, St Mary at Birch and St Michael at Tonge.

Above: left, Langley Hall, right, Middleton Parish Church

Right: The church in the 19th century.

Turnpikes and Toll Bars

Middleton was once on the route of a Roman road, linking Chester and York. Manchester Old Road and Long Street formed part of the main highway from Manchester to York. Both were turnpiked in 1754, following the Manchester and Rochdale Turnpike Act.

The route from Manchester was via Crumpsall, with a toll house at Rhodes, later known as Manchester Old Road. In 1804, an alternative route was launched, via Blackley, which later became Manchester New Road. Heywood Road, now known as Heywood Old Road, was also turnpiked.

Many of Middleton’s old lanes crossed private estates, and some of their toll bars remained as recently as the 1940s. Landowners even stipulated what materials should be used to build houses on such streets.

Harbord Harbord, for example, decreed that houses 92-96 Boardman Lane should have walls 15 inches thick, with bricks from his own Middleton Brick Company. He also insisted that any grain grown on land at the rear had to be milled at Middleton Mill – which just happened to be owned by him too!

Left: Birch Toll Bar, Heywood Road c1860.

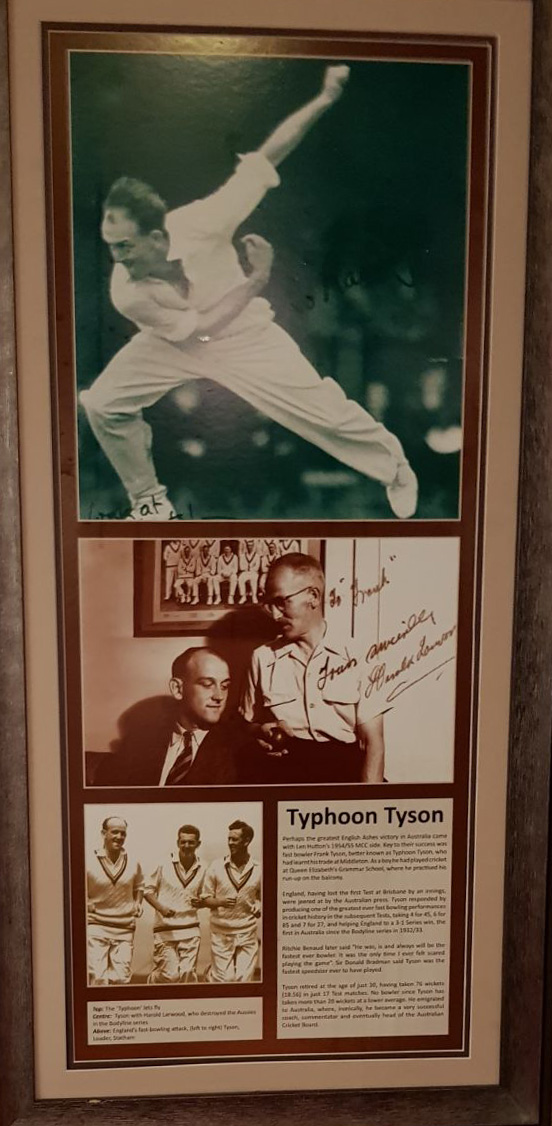

Photographs and text about Frank Tyson.

The text reads: Perhaps the greatest English Ashes victory in Australia came with Len Hutton’s 1954/55 MCC side. Key to their success was fast bowler Frank Tyson, better known as Typhoon Tyson, who had learnt his trade at Middleton. As a boy he had played cricket at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School, where he practiced his run-up on the balcony.

England, having lost the first Test at Brisbane by an innings, were jeered at by the Australian press. Tyson responded by producing one of the greatest ever fast bowling performances in cricket history in the subsequent Tests, taking 4 for 45, 6 for 85 and 7 for 27, and helping England to a 3-1 Series win, the first in Australia since the Bodyline series in 1932/33.

Ritchie Benuad later said “He was, is and always will be the fastest ever bowler. It was the only time I ever felt scared playing the game”. Sir Donald Bradman said Tyson was the fastest speedster ever to have played.

Tyson retired at the age of just 30, having taken 76 wickets (18.56) in just 17 Test matches. No bowler since Tyson has taken more than 20 wickets at a lower average. He emigrated to Australia, where, ironically, he became a very successful coach, commentator and eventually head of the Australian Cricket Board.

A photograph of Market Place, Middleton, c1910.

J D Wetherspoon would like to thank Colette Wagstaffe for supplying information about the history of this building. Colette, a local photographer, artist, and historian, has been researching the history of Middleton’s architecture for over fifteen years. She is well known for her work on the community website entitled Middletonia. Her book Middleton Through Time was published in 2013.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk