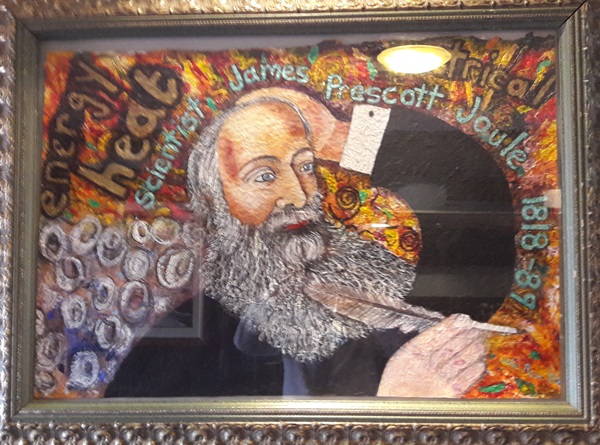

This is named after the physicist James Prescott Joule, famous for his experiments in heat. Joule lived and worked at 12 Wardle Road for the last 17 years of his life. A memorial to him was unveiled in nearby Worthington Park in 1905. There is also a plaque in Westminster Abbey, directly beneath Charles Darwin’s memorial.

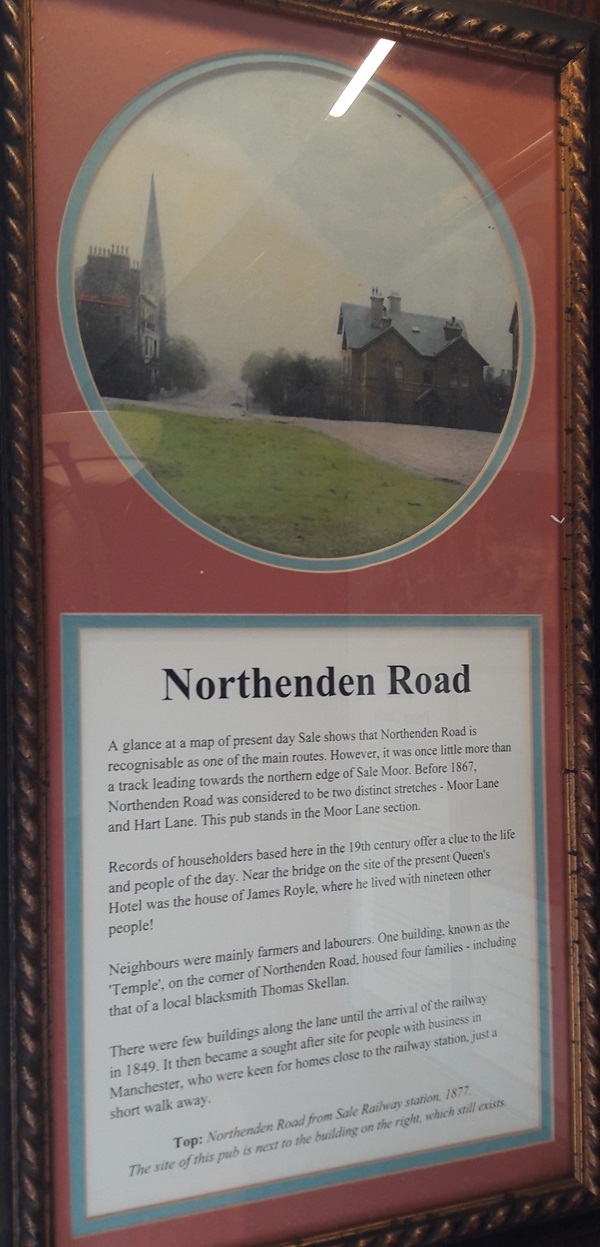

A print and text about Northenden Road.

The text reads: A glance at a map of present day Sale shows that Northenden Road is recognisable as one of the main routes. However, it was once little more than a track leading towards the northern edge of Sale Moor. Before 1867, Northenden Road was considered to be two distinct stretches – Moor Lane and Hart Lane. This pub stands in the Moor Lane section.

Records of households based here in the 19th century offer a clue to the life and people of the day. Near the bridge on the site of the present Queen’s Hotel was the house of James Royle, where he lived with nineteen other people!

Neighbours were mainly farmers and labourers. One building, known as the Temple on the corner of Northenden Road, housed four families – including that of a local blacksmith Thomas Skellan.

There were few buildings along the lane until the arrival of the railway in 1849. It then became a sought after site for people with business in Manchester, who were keen for homes close to the railway station, just a short walk away.

Top: Northenden Road from Sale Railway station, 1877. The site of this pub is next to the building on the right, which still exists.

Prints and text about John Benjamin Dancer.

The text reads: John Benjamin Dancer is buried in Brooklands Cemetery in Sale. He was a scientific instrument maker and he invented the stereoscopic camera and was a pioneer in microphotography.

Dancer assisted James Prescott Joule with the development of scientific instruments, such as apparatus for measuring the internal capacity of the bore of thermometer tubes, a tangent galvanometer, and other devices useful in Joule’s research.

In 1842 Dancer took a daguerreotype from the top of the Royal Exchange which is the earliest known photograph showing part of Manchester.

His photograph of a flea, shown at a meeting of scientists in Liverpool in 1840, showed the advantages photography could bring to microscopy, and began the technological advantages that led to photomicrography as we know it today.

Top left: John Benjamin Dancer

Above: Dancer’s stereoscopic camera

Right: Images that Dancer’s pioneering work made possible: top, single cell algae, below, a bumble bee.

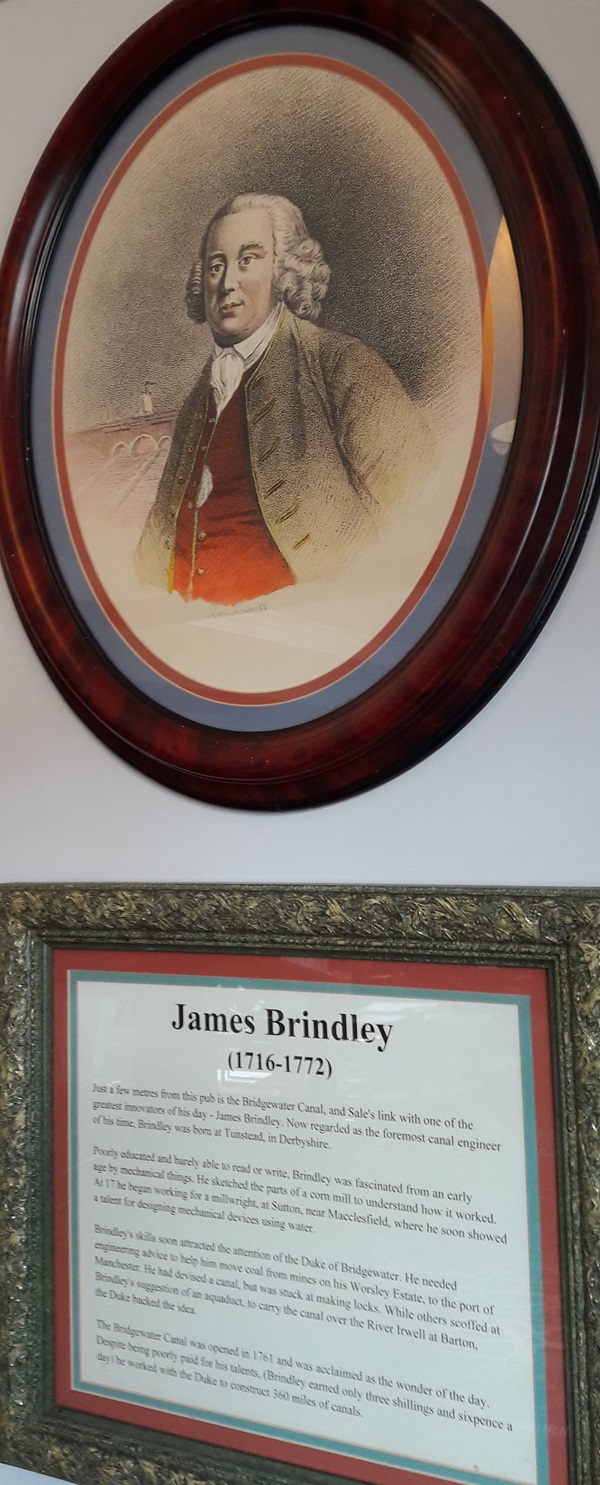

An illustration and text about James Brindley.

The text reads: Just a few metres from this pub is the Bridgewater Canal, and Sale’s link with one of the greatest innovators of his day – James Brindley. Now regarded as the foremost canal engineer of his time, Brindley was born at Tunstead, in Derbyshire.

Poorly educated and barely able to read or write, Brindley was fascinated from an early age by mechanical things. He sketched the parts of a corn mill to understand how it worked. At 17 he began working for a millwright, at Sutton, near Macclesfield, where he soon showed a talent for designing mechanical devices using water.

Brindley’s skills soon attracted the attention of the Duke of Bridgewater. He needed engineering advice to help him move coal from mines on his Worsley Estate, to the port of Manchester. He had devised a canal, but was stuck at making locks. While others scoffed at Brindley’s suggestion of an aqueduct, to carry the canal over the River Irwell at Barton, the Duke backed the idea.

The Bridgewater Canal was opened in 1761 and was acclaimed as the wonder of the day. Despite being poorly paid for his talents, (Brindley earned only three shillings and sixpence a day) he worked with the Duke to construct 360 miles of canals.

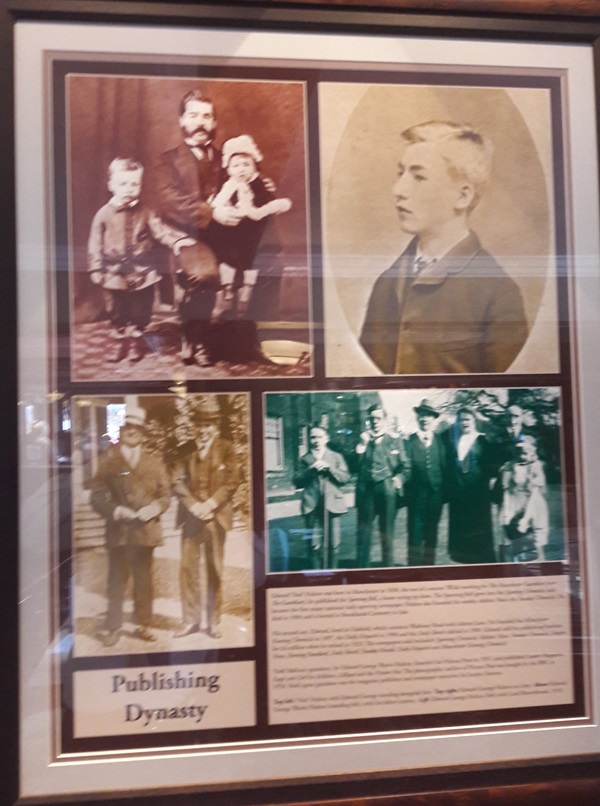

Photographs and text about Edward ‘Ned’ Hulton.

The text reads: Edward ‘Ned’ Hulton was born in Manchester in 1838, the son of a weaver. While working for The Manchester Guardian (now The Guardian), he published the Sporting Bell, a horse racing tip sheet. The Sporting Bell grew into the Sporting Chronicle, and became the first major national daily sporting newspaper. Hulton also founded the weekly Athletic News, the Sunday Chronicle. He died in 1904 and is buried in Brooklands Cemetery in Sale.

His second son, Edward, lived in Oakfield, which connects Washway Road with Ashton Lane. He founded the Manchester Evening Chronicle in 1897, the Daily Dispatch in 1900 and the Daily Sketch tabloid in 1909. Edward sold his publishing business for £6 million when he retired in 1923. The newspapers sold included: Sporting Chronicle, Athletic News, Sunday Chronicle, Empire News, Evening Standard, Daily Sketch, Sunday Herald, Daily Dispatch and Manchester Evening Chronicle.

‘Ned’ Hulton’s grandson, Sir Edward George Warris Hulton, founded the Hulton Press in 1937, and published Leader Magazine, Eagle and Girl for children, Lilliput and the Picture Post. The photographic archive of Picture Post was brought by the BBC in 1958. Ned’s great-grandson was the magazine publisher and newspaper executive Sir Jocelyn Stevens.

Top left: ‘Ned’ Hulton with Edward George standing alongside him

Top right: Edward George Hulton as a boy

Above: Edward George Warris Hulton (standing left), with his father (centre)

Left: Edward George Hulton (left) with Lord Beaverbrook, 1918.

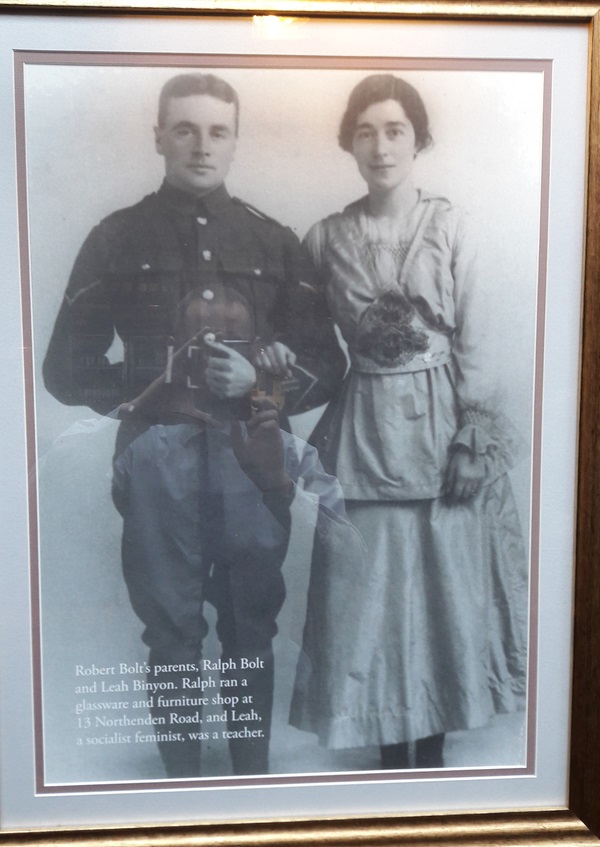

A photograph and text about Ralph Bolt and Leah Binyon.

The text reads: Robert Bolt’s parents, Ralph Bolt and Leah Binyon. Ralph ran a glassware and furniture shop at 13 Northenden Road, and Leah, a socialist feminist, was a teacher.

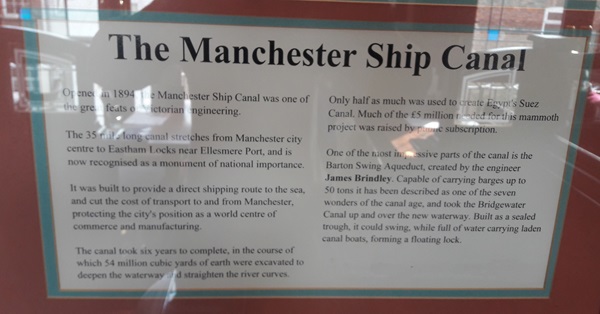

Text about the Manchester Ship Canal.

The text reads: Opened in 1894 the Manchester Ship Canal was one of the great feats of Victorian engineering.

The 35 mile long canal stretches from Manchester city centre to Eastham Locks near Ellesmere Port, and is now recognised as a monument of national importance.

It was built to provide a direct shipping route to the sea, and cut the cost of transport to and from Manchester, protecting the city’s position as a world centre of commerce and manufacturing.

The canal took six years to complete, in the course of which 54 million cubic yards of earth were excavated to deepen the waterway and straighten the river curves.

Only half as much was used to create Egypt’s Suez Canal. Much of the £5 million needed for this mammoth project was raised by public subscription.

One of the most impressive parts of the canal is the Barton Swing Aqueduct, created by the engineer James Brindley. Capable of carrying barges up to 50 tons it has been described as one of the seven wonders of the canal age, and took the Bridgewater Canal up and over the new waterway. Built as a sealed trough, it could swing, while full of water carrying laden canal boats, forming a floating lock.

Top: Locks and railway viaduct at Irlam

Above: left, James Brindley, right, the Barton Aqueduct.

A painting entitled JP Joule’s Home.

A painting entitled James Prescott Joule.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk