This building is on the site of Blacklers department store, opened by Richard John Blackler in 1908, when he was only 36 years old. He lived at Amberley Park and later at Fulwood Road, until his death in 1919. The store was destroyed in 1941 during the Blitz. Only the steel skeleton remained, much of it utilised in the rebuilding after the war. It took 10 years in planning and four years to build, before the brand-new store opened in 1955.

A piece of text about the history of The Richard John Blackler.

The text reads: The building you are now in is situated on the site of Blacklers department store.

Opened by Richard John Blackler in 1908, the original store quickly flourished, and became a byword for value and service in Merseyside and beyond.

Blackler was only 36 years old when he opened his store. He began by specialising in millinery and women’s stockings, but soon spread his wings, priding himself on supplying everyone with anything they could wish for. He lived at Amberley park, and later at Fulwood Road, until his death in 1919.

The store was destroyed in 1941 during the blitz. Only the steel skeleton remained, and much of it was utilised in the rebuilding that took place after the war. It took ten years in planning, and four years to build, before the brand new store opened in 1955, having partially re-opened in 1953.

Blacklers was later run by the Wallis family. It had a reputation for looking after its staff, as well as its customers. Prior to the blitz it employed 1200 people.

The store was greatly enjoyed by both young and old. The young especially would never forget its famous Christmas grotto, and the well-remembered rocking horse, that transferred to Alder hey children’s hospital when Blacklers finally closed down in 1988.

A framed drawing and text about Liverpool’s North Shore.

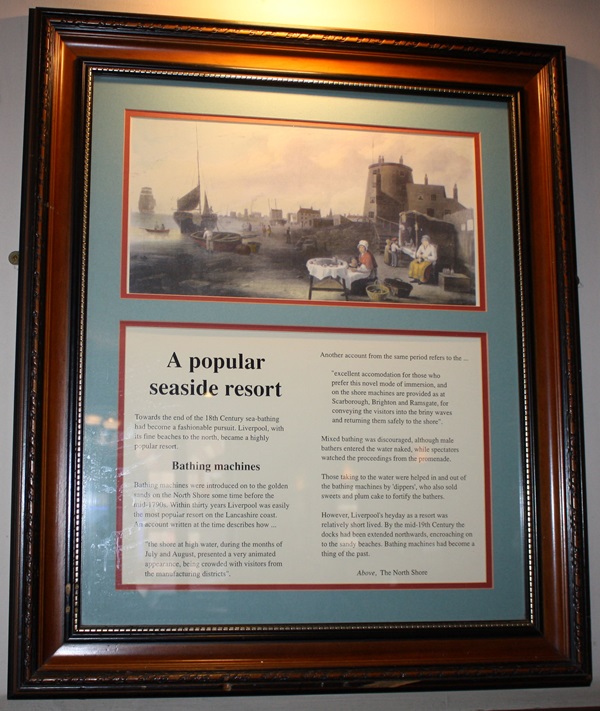

The text reads: Towards the end of the 18th Century sea-bathing had become a fashionable pursuit. Liverpool, with its fine beaches to the north, became a highly popular resort.

Bathing machines were introduced on to the golden sands on the North Shore some time before the mid-1790s. Within thirty years Liverpool was easily the most popular resort on the Lancashire coast. An account written at the time describes how…

“the shore at high water, during the months of July and August, presented a very animated appearance, being crowded with visitors from the manufacturing districts”.

Another account from the same period refers to the…

“excellent accommodation for those who prefer this novel mode of immersion and on the shore machines are provided as at Scarborough, Brighton and Ramsgate, for conveying the visitors into the briny waves and returning them safely to shore”.

Mixed bathing was discouraged, although male bathers entered the water naked, while spectators watched the proceedings from the promenade.

Those taking to the water were helped in and out of the bathing machines by ‘dippers’, who also sold sweets and plum cakes to fortify the bathers.

However, Liverpool’s heyday as a resort was relatively short lived. By the mid-19th Century the docks had been extended northwards, encroaching on to the sandy beaches. Bathing machines had become a thing of the past.

Above, The North Shore

A framed drawing and text about the Great Western and the Great Britain steamships.

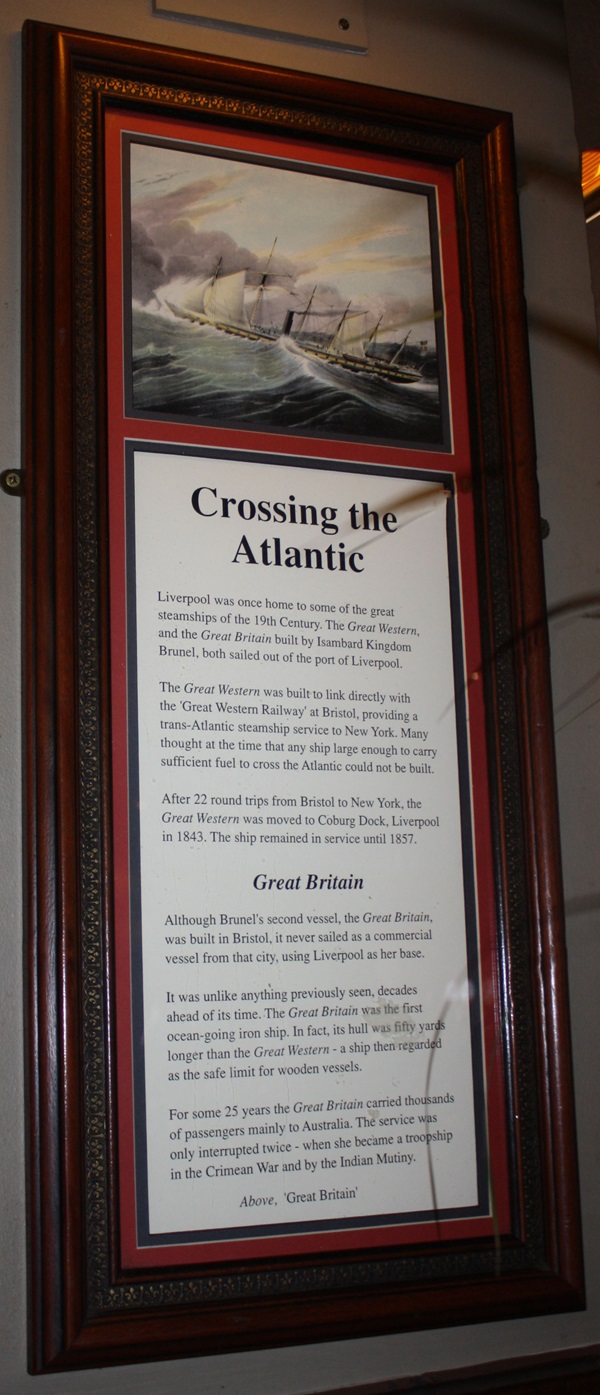

The text reads: Liverpool was once home to some of the great steamships of the 19th Century. The Great Western, and the Great Britain built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, both sailed out of the port of Liverpool.

The Great Western was built to link directly with the ‘Great Western Railway’ at Bristol, providing a trans-Atlantic steamship service to New York. Many thought at the time that any ship large enough to carry sufficient fuel to cross the Atlantic could not be built.

After 22 round trips from Bristol to New York, the Great Western was moved along to Coburg Dock, Liverpool in 1843. The ship remained in service until 1857.

Although Brunel’s second vessel, the Great Britain, was built in Bristol, it never sailed as a commercial vessel from that city, using Liverpool as her base.

It was unlike anything previously seen, decades ahead of its time. The Great Britain was the first ocean-going iron ship. In fact, its hull was fifty yards longer than the Great Western – a ship then regarded as the safe limit for wooden vessels.

For some 25 years the Great Britain carried thousands of passengers mainly to Australia. The service was only interrupted twice – when she became a troopship in the Crimean War and by the Indian Mutiny.

Above, ‘Great Britain’

Framed drawings and text about Liverpool’s docks.

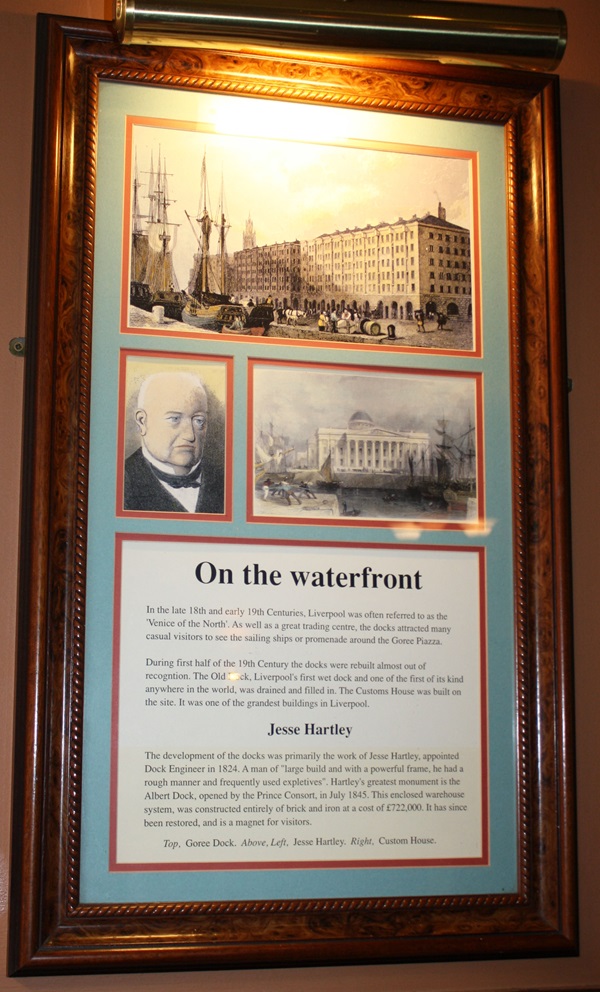

The text reads: In the late 18th Century and early 19th Centuries, Liverpool was often referred to as the ‘Venice of the North’. As well as a great trading centre, the docks attracted many casual visitors to see the sailing ships or promenade around the Goree Piazza.

During the first half of the 19th Century the docks were rebuilt almost out of recognition. The Old Dock, Liverpool’s first wet dock and one of the first of its kind anywhere in the world, was drained and filled in. The Customs House was built on the site. It was one of the grandest buildings in Liverpool.

The development of the docks was primarily the work of Jesse Hartley, appointed Dock Engineer in 1824. A man of “large build and with a powerful frame, he had a rough manner and frequently used expletives”. Hartley’s greatest monument is the Albert Dock, opened by Prince Consort, in July 1845. This enclosed Warehouse system, was constructed entirely of brick and iron at a cost of £722,000. It has since been restored, and is a magnet for visitors.

Top, Goree Dock. Above, Left, Jesse Hartley. Right, Custom House.

A framed photograph of The Aquitania, Liverpool Docks c.1910.

A framed photograph of The Landing Stage, Liverpool c.1906.

Framed drawings and text about the slave trade.

The text reads: During the 17th Century the slave trade operated exclusively out of London. By the early 18th Century more than half the vessels engaged in ‘the Africa trade’ sailed out of Bristol. By the latter half of that century Liverpool was easily the leading ‘slave’ port.

The slaves were captured by dealers in Africa and exchanged for items such as tobacco and firearms. These goods, often second-hand, were taken out by ships from England, which then set sail with human cargos.

A captain of one ship made the following entry describing the appalling conditions of the 200 or so slaves on board his vessel: “the slaves lie in two rows, one above the other, on each side of the ship, close to each other, like books on a shelf. I have known them so close, that the shelf would not easily contain one more… the poor creatures are likewise in irons which makes it difficult for them to rise or lie down”.

The slaves were shipped across the Atlantic to work in plantations in the southern colonies in America, the West Indies and Spanish America. The ships then returned to England laden with goods such as rum and tobacco.

Only a handful of slaves were brought into England, where they were able to speak of their experiences. The campaigning work of various reformers eventually made the horrors of the slave trade more widely known. The trade was abolished in the early 19th Century.

Above: Left, a slave ship. Right, A Liverpool slave captain.

Framed drawings and text about the abolition of the slave trade.

The text reads: The campaign against slavery was pioneered by men like Thomas Clarkson and other Quakers, who gathered information from sailors and captains of slave vessels. However, these early pioneers did not have a voice in Parliament.

William Wilberforce and others founded a ‘Society for the Abolition of Slavery’ in 1787, which led, the following year, to the formation of a Committee in the House of Commons to examine the slave trade.

Wilberforce brought in his first motion for the abolition of slavery in 1789, but failed to get the support of the Commons. Outside of Parliament opposition came mainly from Liverpool merchants.

There was also discontent among many local seaman who feared losing their jobs. In fact, they threatened Thomas Clarkson, when he came to Liverpool to gather information to present at the Committee in the House of Commons.

William Roscoe was another who was set upon by angry sailors. Roscoe was a local man who rose from humble beginnings to become a successful lawyer. He was a long time campaigner against the slave trade and, for a short time, MP for Liverpool.

In spite of intimidation, the campaign continued and in 1807 Parliament abolished slavery, although it was still legal in the Empire. Wilberforce carried on campaigning, but had to wait until 1833 – when he was a dying man – before he was successful.

Above: Left, Thomas Clarkson

Right, William Roscoe

Right: William Wilberforce

A framed drawing and text about John Masefield.

The text reads: Born in land-locked Herefordshire in 1878, John Masefield came to Liverpool at the age of thirteen to join a training ship. His first impressions of the old wooden sailing vessels on the River Mersey and the Liverpool waterfront stayed with him all his life, featuring in his poems and prose:

Though I tell many, there must still be others,

McVickar Marshall’s ships and Fernie Brothers’,

Lochs, Counties, Shires, Drums, the countless lines

Whose house-flags all were once familiar signs

At high main-trucks on Mersey’s windy ways

When sunlight made the wind-white water blaze.

Their names bring back old mornings, when the docks

Shone with their house-flags and their painted blocks.

Their raking masts below the Custom House

And all the marvellous beauty of their bows.

John Masefield became Poet Laureate in 1930. He died in 1967.

A framed drawing and text about John Wesley.

The text reads: John Wesley, the leader and founder of the Methodist Movement, was certainly no stranger to this area. He made several visits to Liverpool in the 1750s and 60s and preached many times in Chester.

His preaching took him the length and breadth of England and Wales. When he died in 1791 Wesley had travelled some 250,000 miles, mainly on horseback, and had preached over 40,000 sermons, averaging 15 each week, often to vast crowds. Wesley also wrote extensively and founded the Methodist Magazine. The enormous popularity of his works earned him more than £30,000, which he gave to charity.

During his first visit to Liverpool in 1755, Wesley recorded his observations of what was then a fast developing town.

“At six in the morning, Tuesday the 15th, I preached to a large and serious congregation, and then went to Liverpool, one of the neatest, best-built towns I have seen in England”.

“I think it full twice as large as Chester, most of the streets are quite straight. Two thirds of the town, we are informed have been added within these forty years. If it continues to increase in the same proportion, in forty years more it will nearly equal Bristol. The people in general are the most mild and courteous I ever saw in a seaport town; as indeed appears by their friendly behaviour, not only to the Jews and Papists who live among them, but even to the Methodists”.

Above, Western Chapel, Stanhope Street, 1829.

A framed drawing and text about Vincenzo Lunardi.

The text reads: In the summer of 1784 the ballooning craze which had swept through France crossed the English Channel. Vincenzo Lunardi was the first to make an ascent in England, and he subsequently toured the country as a professional balloonist.

One of his demonstration flights was staged at the North Fort, Liverpool. The ascent was behind schedule as Lunardi had difficulty inflating his balloon. To help him take off he reduced the weight in the basket by throwing out various items, his life jacket among them.

Lunardi waved triumphantly to the large appreciative crowd as his balloon floated upwards. Unfortunately the wind blew him out to sea. However, Lunardi managed to land his craft almost an hour and a half later in the middle of a field.

Above, Lunardi and guests in the ascendant.

Framed drawings and text about Liverpool Castle.

The text reads: Standing on the highest point overlooking the ‘liver’ or ‘lever’ pool, Liverpool Castle was by far the most impressive and important building in the area. Built for William de Ferrer, Earl of Derby, it was completed in 1235, replacing an earlier timber-built castle at West Derby.

The new castle was an impressive stone fortress surrounded by a moat, designed to withstand both siege and sudden attack. The Castle underwent its first siege in the early 14th Century during the ‘Banastre Revolt’.

Following the uprising King Edward II visited the area, and stayed in Liverpool Castle for a week in October 1323.

Eventually there was little need for such military fortress, and by the early 18th Century the Castle had been bought by the town council.

During the 1720s people still lived in the ruins of the round corner towers, but in 1726 the council ordered the last remaining section of the outer wall (at the end of Lord Street) to be demolished. St George’s Church was built on site.

Construction on Liverpool castle began shortly after King John decided to establish a ‘new town’ here in 1207. It was built on a grid design, and all the seven original street survive. However, only Castle Street, Dale Street and Chapel Street still have their original names.

Right, Top, Liverpool Castle

Below, View of Liverpool, 1680.

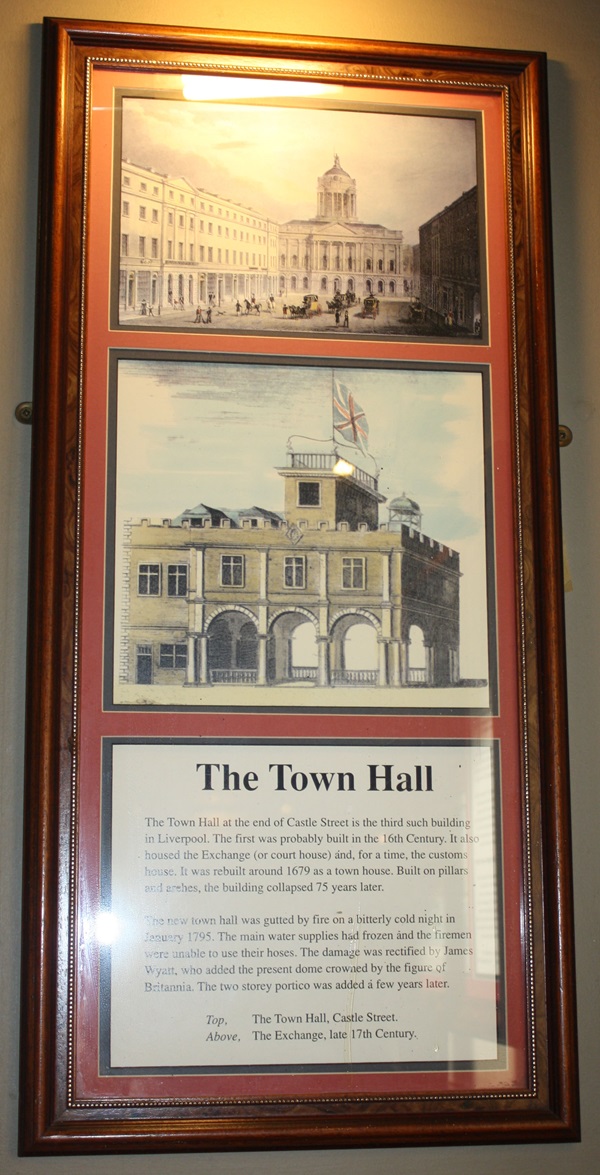

Framed drawings and text about the town hall.

The text reads: The Town Hall at the end of Castle Street is the third such building in Liverpool. The first was probably built in the 16th Century. It also housed the Exchange (or court house) and, for a time, the customs house. It was rebuilt around 1679 as a town house. Built on pillars and arches, the building collapsed 75 years later.

The new town hall was gutted by fire on a bitterly cold night in January 1795. The main water supplies had frozen and the firemen were unable to use their hoses. The damage was rectified by James Wyatt, who added the present dome crowned by the figure of Britannia. The two story portico was added a few years later.

Top, The Town Hall, Castle Street.

Above, The Exchange, late 17th Century.

A framed photograph of The Empire and North Western Hotel, Liverpool c.1905.

A framed photograph of Lime Street, Liverpool c.1906.

A framed photograph of Lime Street Station, Liverpool c.1908.

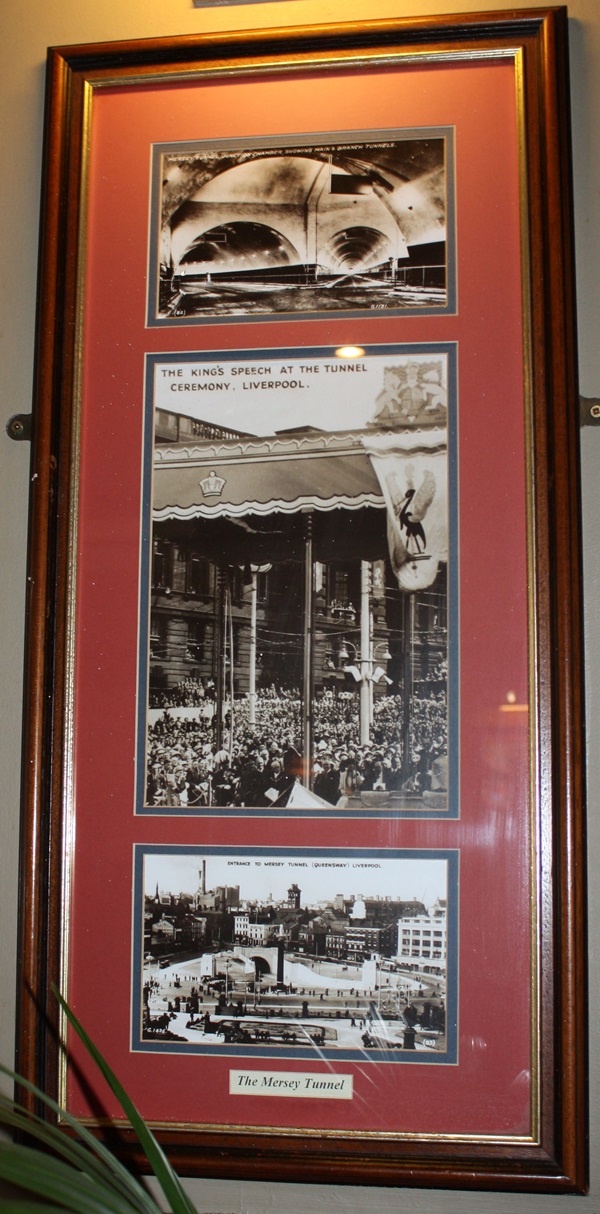

Framed photographs of the Mersey Tunnel.

A framed photograph of the Liverpool Art Gallery c.1909.

A framed photograph of The Hippodrome, Liverpool c.1909.

Internal photographs of inside the pub.

The layout remains similar to that of the original – which was destroyed during the Blitz.

External photograph of the building – rebuilt in 1955.

External photograph of the building – front.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk