This has been a public house for more than a century. Mostly, the three-storey building (which extends along Victoria Road) was the Empire (not to be confused with the nearby Empire Theatre – now a nightclub). The Empire was originally named the Empire Hotel. The building is recorded in the 1891 census as the Swatters Carr Hotel Public House – Swatters (or Swathers) Carr after the isolated farmhouse, first recorded on a map dated 1618.

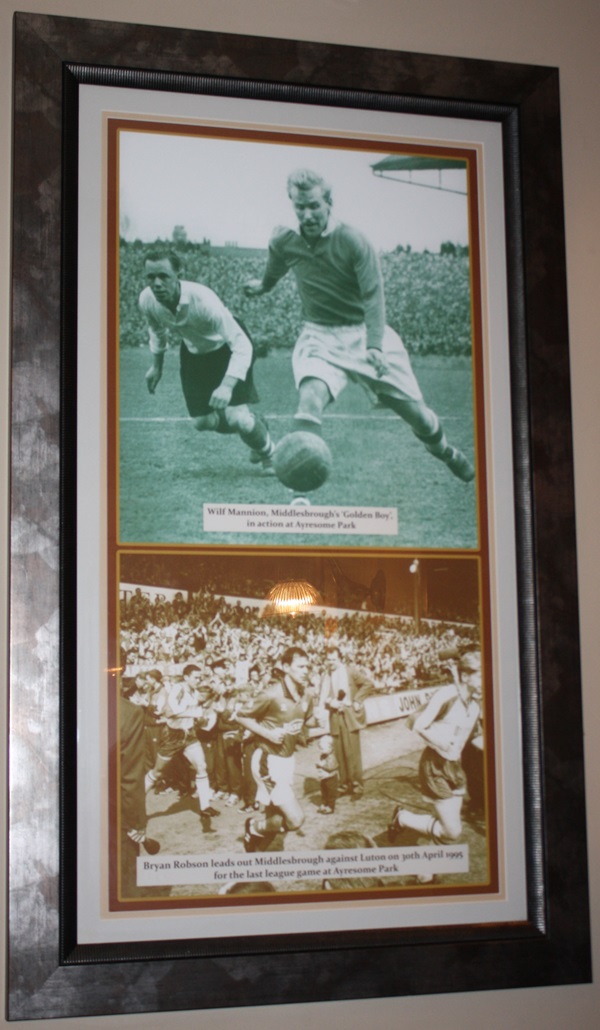

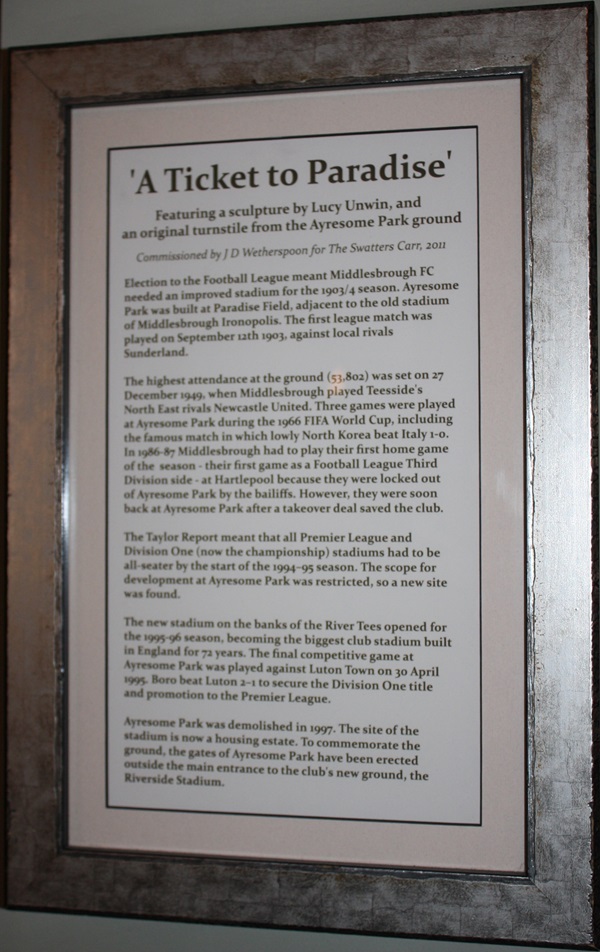

Photographs of Middlesbrough Football Club playing at Ayresome Park.

Above: Wilf Mannion, Middlesbrough’s ‘Golden boy’, in action at Ayresome Park.

Below: Bryan Robson leads out Middlesbrough against Luton on 30th April 1995 for the last league game at Ayresome Park.

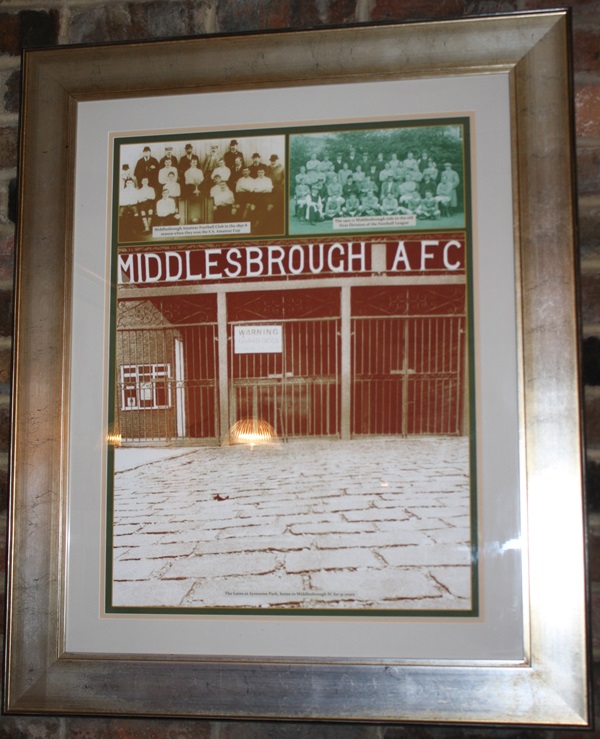

Photographs of Middlesbrough Football Club and Ayresome Park.

Left: Middlesbrough Amateur Football Club in 1897, a season when they won the F.A. Amateur Cup.

Below: The Gates at Ayresome Park, home to Middlesbrough FC.

Photographs and text about Middlesbrough FC.

The text reads: Middlesbrough Football Club played its first matches, more than a century ago, in nearby Albert Park. However, it soon switched to Swatters Carr Field and the Cricket Club Field, close to these premises.

In 1889 a dispute about turning professional resulted in a breakaway group forming a new team called ‘Middlesbrough Ironopolis’. The name was chosen to reflect the importance of heavy industry in the town, which supplied iron and steel for railways, bridges and other landmarks all over the world.

The professional ‘Ironopolis’ team played at Paradise Ground, off Linthorpe Road, until it folded in 1894. In 1903, the original Middlesbrough club moved to Ayresome Park, a new stadium next to Paradise Ground, which was its home for the next 92 years.

Above: Middlesbrough AFC at the end of the 1894-5 season with the FA Amateur Cup, Northern League Trophy and Senior Cup

Left: A Middlesbrough Ironopolis supporters badge

Right: Middlesbrough AFC supporters club badge, 1895.

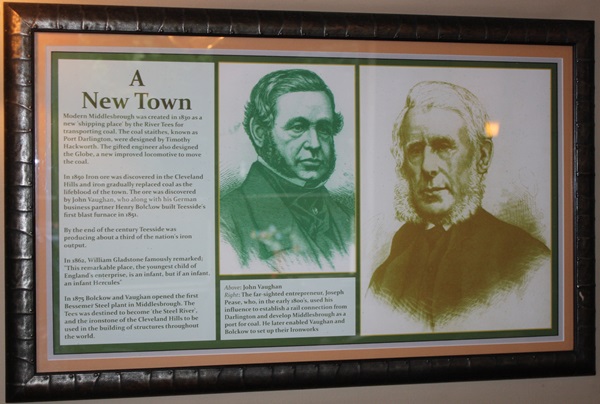

Illustrations and text about industries in Middlesbrough.

The text reads: Modern Middlesbrough was created in 1830 as a new ‘shipping place’ by the River Tees for transporting coal. The coal staithes, known as Port Darlington, were designed by Timothy Hackworth. The gifted engineer also designed the Globe, a new improved locomotive to move the coal.

In 1850 Iron ore was discovered in the Cleveland Hills and iron gradually replaced coal as the lifeblood of the town. The ore was discovered by John Vaughan, who along with his German business partner Henry Bolckow built Teesside’s first blast furnace in 1851.

By the end of the century Teesside was producing about a third of the nation’s iron output.

In 1862, William Gladstone famously remarked; “This remarkable place, the youngest child of England’s enterprise, is an infant, but if an infant, an infant Hercules”.

In 1875 Bolckow and Vaughan opened the first Bessemer Steel plant in Middlesbrough. The Tees was destined to become ‘the Steel River’, and the ironstone of the Cleveland Hills to be used in the building of the structures throughout the world.

Above: John Vaughan

Right: The far-sighted entrepreneur, Joseph Pease, who, in the early 1800’s, used his influence to establish a rail connection from Darlington and develop Middlesbrough as a port for coal. He later enabled Vaughan and Bolckow to set up their Ironworks.

Illustrations of Port Darlington and the Ironworks.

Left: Timothy Hackworth who designed the coal staithes at Port Darlington

Above: Port Darlington in the late 1830’sRight: Bolckow and Vaughan’s Ironworks in 1860.

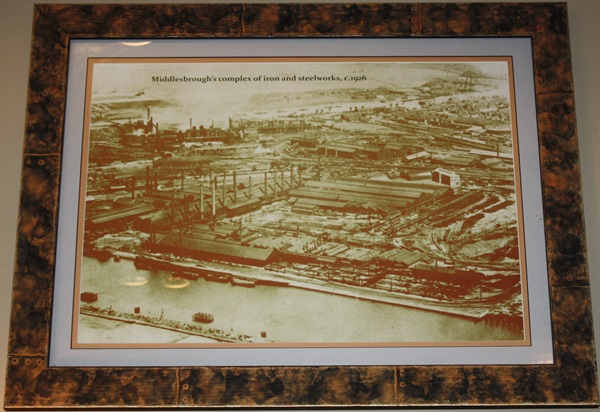

A photograph of Middlesbrough’s complex of iron and steel works, c.1926.

An illustration of Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan and the sisters they married: the men dreaming of commercial success and the women of domestic bliss.

Photographs and text about Swatters Carr.

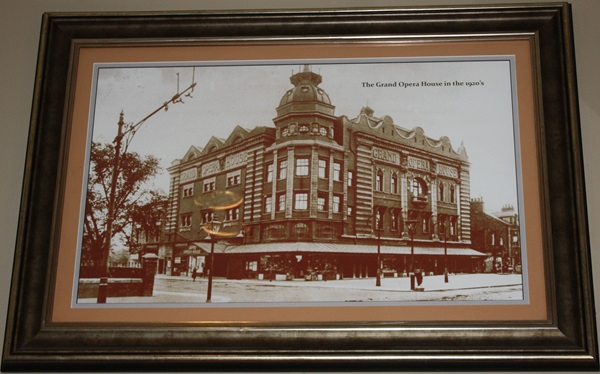

The text reads: Swatters Carr was an isolated farmhouse that stood near this site. During the late 19th century the area developed into a suburb and 1903 the farmhouse had been replaced by the Grand Opera House.

The Grand Opera House attracted performers such as Charlie Chaplin, then a young man on his way to fame and fortune. Gracie Fields, star of music hall and later cinema, also trod the boards at this grand old theatre.

In 1930, the ‘Grand’ reopened as the Gaumont cinema, which was replaced by offices in 1964. The cinema site is connected to the building that you are now in by Ashburton Terrace, much altered since it was built in late Victorian times, although three original facades still remain.

Above and left: Images of the Grand Opera House, including (above left) a view of Linthorpe Road from outside this site showing Ashburton Terrace with the Opera House in the middle distance.

A photograph of the Grand Opera House in the 1920’s.

A photograph of 228 Linthorpe Road.

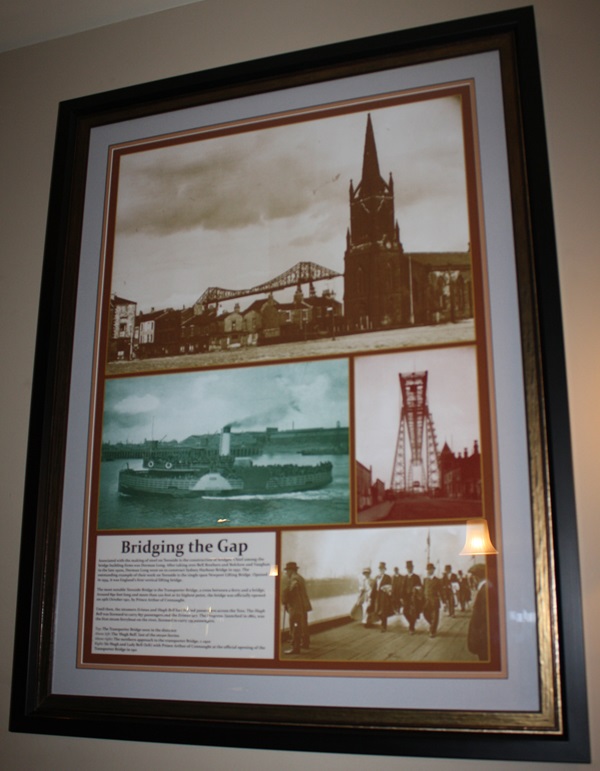

Photographs and text about bridge construction.

The text reads: Associated with the making of steel on Teesside is the construction of bridges. Chief among the bridge building firms was Dorman Long. After taking over Bell Brothers and Bolckow and Vaughan in the late 1920’s, Dorman Long went on to construct Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. The outstanding example of their work on Teesside is the single span Newport Lifting Bridge. Opened in 1934, it was England’s first vertical lifting bridge.

The most notable Teesside Bridge is the Transporter Bridge, a cross between a ferry and a bridge. Around 850 feet long and more than 22 feet at its highest point, the bridge was officially opened on 19th October 1911, by Prince Arthur of Connaught.

Until then, the steamers Erimus and Hugh Bell had ferried passengers across the Tees. The Hugh Bell was licensed to carry 857 passengers and the Erimus 927. The Progress, launched in 1862, was the first steam ferryboat on the river, licensed to carry 139 passengers.

Top: The Transporter Bridge seen in the distance

Above left: The ‘Hugh Bell’, last of the steam ferries

Above right: The northern approach to the transporter Bridge, c.1920

Right: Sir Hugh and Lady Bell (left) with Prince Arthur of Connaught at the official opening of the transporter bridge in 1911.

A photograph of workmen being ferried from Port Clarence via the Transporter Bridge, c.1920.

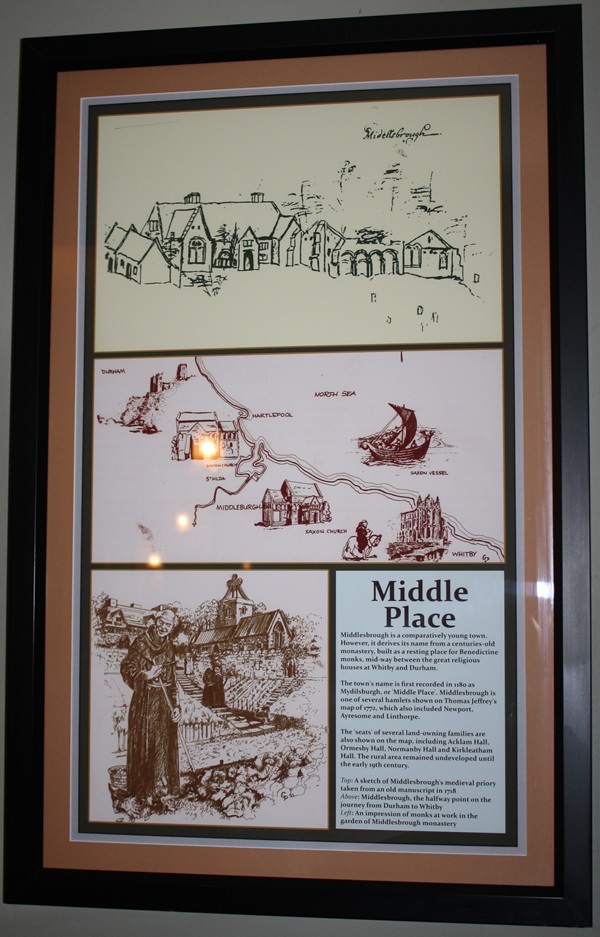

Illustrations and text about how Middlesbrough got its name.

The text reads: Middlesbrough is a comparatively young town. However, it derives its name from a centuries-old monastery, built as a resting place for Benedictine monks, mid-way between the great religious houses at Whitby and Durham.

The town’s name is first recorded in 1180 as Mydilsburgh, or ‘Middle Place’. Middlesbrough is one of several hamlets shown on Thomas Jeffery’s map of 1772, which also included Acklam Hall, Ormesby Hall, Normanby Hall and Kirkleatham Hall. The rural area remained underdeveloped until the early 19th century.

Top: A sketch of Middlesbrough’s medieval priory taken from an old manuscript in 1718

Above: Middlesbrough, the halfway point on the journey from Durham to Whitby

Left: An impression of monks at work in the garden of Middlesbrough monastery.

Prints, an illustration and text about Captain Cook.

The text reads: The famous navigator and explorer was born in Marton (now part of Middlesbrough) in 1728. The first of his great sea voyages took him to the Pacific, on board the Endeavour.

Between 1772 and 1775, Cook was given two ships for another voyage of exploration. With the Resolution as his flagship, he completed the first west-east circumnavigation in high latitudes. In 1776 Cook again set sail on the Resolution to seek a north-west passage around Canada.

The long arduous search was unsuccessful. Cook returned to Hawaii, where he was killed on the beach in a fracas with natives. In his home town, he is commemorated by Captain Cook Square, where the Wetherspoons Lloyds No.1 Bar ‘The Resolution’ opened in July 2002.

Top: A painting of the death of Captain Cook by George Carter, 1779

Above: The remains of Captain Cook’s birthplace at Marton, c.1885

Right: Watercolour of the ‘Resolution’ by midshipman Henry Roberts.

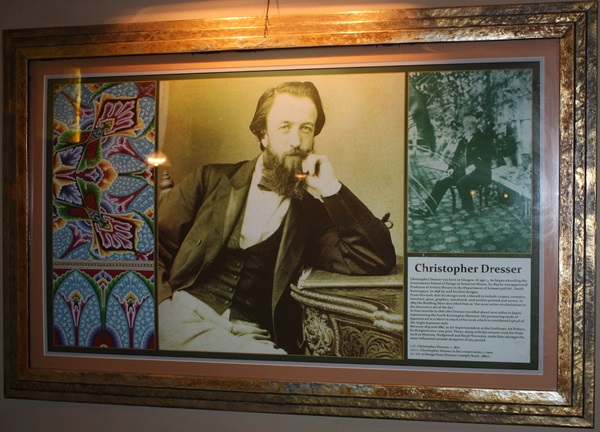

Photographs, prints and text about Christopher Dresser.

The text reads: Christopher Dresser was born in Glasgow. At age 13, he began attending the Government School of Design at Somerset House. In 1855 he was appointed Professor of Artistic Botany in the Department of Science and Art, South Kensington. In 1858 he sold his first designs.

From this early date his design work widened to include carpets, ceramics, furniture, glass, graphic, metalwork, and textiles printed and woven. In 1865 the Building News described him as “the most active revolutioniser in the decorative art of the day”.

In four months in 1976/1877 Dresser travelled about 2000 miles in Japan, representing the South Kensington Museum. His pioneering study of Japanese art is evident in much of his work which is considered typical of the Anglo-Japanese style.

Between 1879 and 1882, as Art Superintendent at the Linthorpe Art Pottery, he designed over 1,000 pots. These, along with his ceramic work for firms such as Mintons, Wedgwood and Royal Worcester, make him amongst the most influential ceramic designers of any period.

Left: Christopher Dresser, c.1900

Above: Christopher Dresser in his conservatory, c.1900

Far left: A Design from Dresser’s sample book, 1880’s.

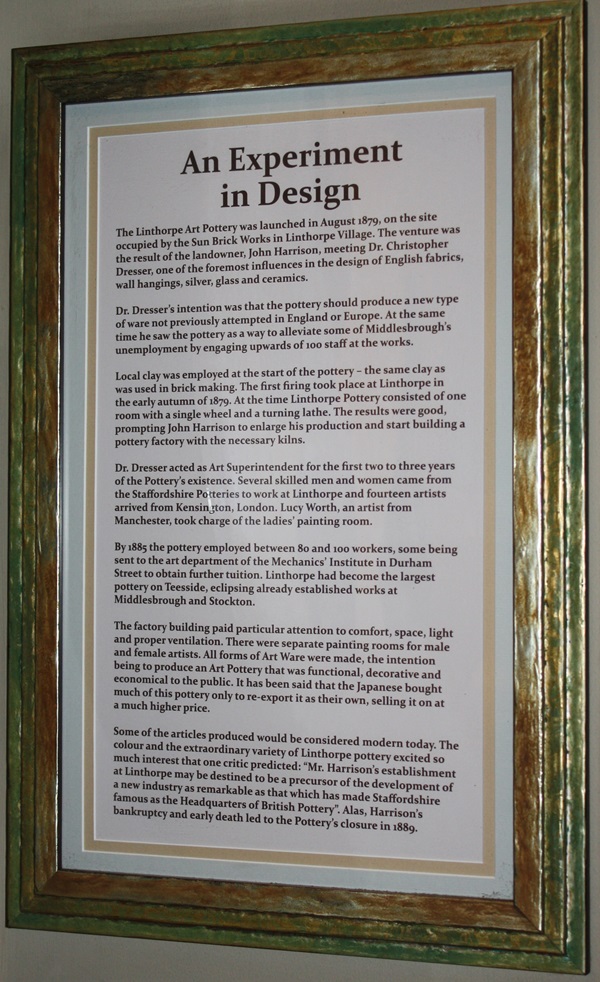

Text about Linthorpe Art Pottery, and a collection of examples.

The text reads: The Linthorpe Art Pottery was launched in August 1879, on the site occupied by the Sun Brick Works in Linthorpe Village. The venture was the result of the landowner, John Harrison, meeting Dr Christopher Dresser, one of the foremost influences in the design of English fabric, wall hangings, silver, glass and ceramics.

Dr. Dresser’s intentions were that the pottery should produce a new type of ware not previously attempted in England or Europe. At the same time he saw the pottery as a way to alleviate some of Middlesbrough’s unemployment by engaging upwards of 100 staff at the works.

Local clay was employed at the start of the pottery – the same clay as was used in brick making. The first firing took place at Linthorpe in the early autumn of 1879. At the time Linthorpe Pottery consisted of one room with a single wheel and a turning lathe. The results were good, prompting John Harrison to enlarge his production and start building a pottery factory with the necessary kilns.

Dr. Dresser acted as Art Superintendent for the first two to three years of the pottery’s existence. Several skilled men and women came from the Staffordshire Potteries to work at Linthorpe and fourteen artists arrived from Kensington, London. Lucy Worth, an artist from Manchester, took charge of the ladies’ painting room.

By 1885 the pottery employed between 80 and 100 workers, some being sent to obtain further tuition. Linthorpe had become the largest pottery on Teesside, eclipsing already established works at Middlesbrough and Stockton.

The factory building paid particular attention to comfort, space, light and proper ventilation. There were separate painting rooms for male and female artists. All forms of Art Ware were made, the intention being to produce an Art Pottery that was functional, decorative and economical to the public. It has been said that the Japanese bought much of this pottery only to re-export it as their own, selling it on at much higher price.

Some of the articles produced would be considered modern today. The colour and the extraordinary variety of Linthorpe pottery excited so much interest that one critic predicted: “Mr. Harrison’s establishment at Linthorpe may be destined to be a precursor of the development of a new industry as the headquarters of British Pottery”. Alas, Harrison’s bankruptcy and early death led to the Pottery’s closure in 1889.

A sculpture entitled A Ticket to Paradise – an original turnstile from the Ayresome Park ground - by Lucy Unwin.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk