Unit 4, Royal Baths, Parliament Street, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, HG1 2RR

Harrogate’s former Royal Baths included the Winter Gardens – built so that visitors could relax and stroll in any weather. Its name lives on in this Wetherspoon pub. During the 1920s, people could relax here, amid potted palms, listening to music from a grand piano. In the 1930s, the Municipal Orchestra played every morning throughout the year, with free admission for the patients of the baths.

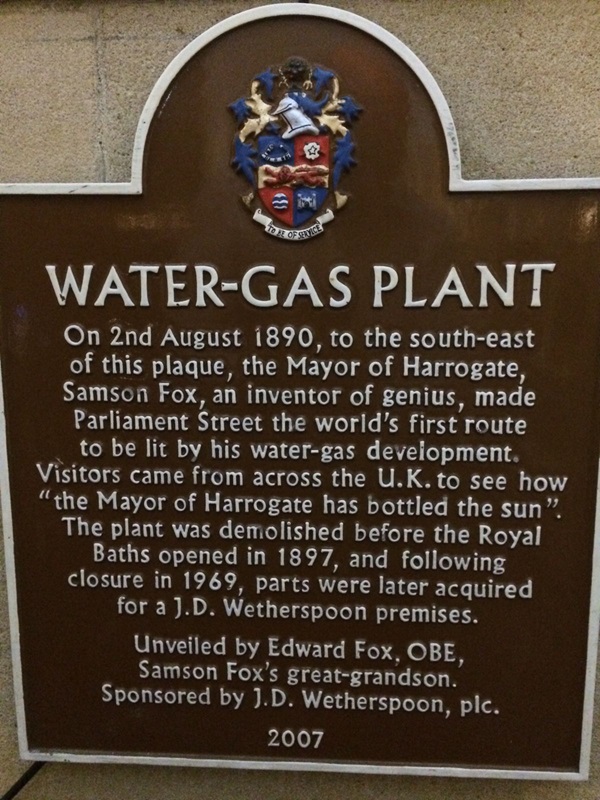

A plaque documenting the history of the water-gas plant.

The plaque reads: On 2 August 1890, to the south-east of this plaque, the Mayor of Harrogate, Samson Fox, an inventor of genius, made Parliament Street the world’s first route to be lit by his water-gas development. Visitors came from across the UK to see how “the Mayor of Harrogate has bottled the sun”. The plant was demolished before the Royal Baths opened in 1897, and following closure in 1969, parts were later acquired for a J D Wetherspoon premises.

Unveiled by Edward Fox, OBE, Samson Fox’s great-grandson. Sponsored by J D Wetherspoon 2007.

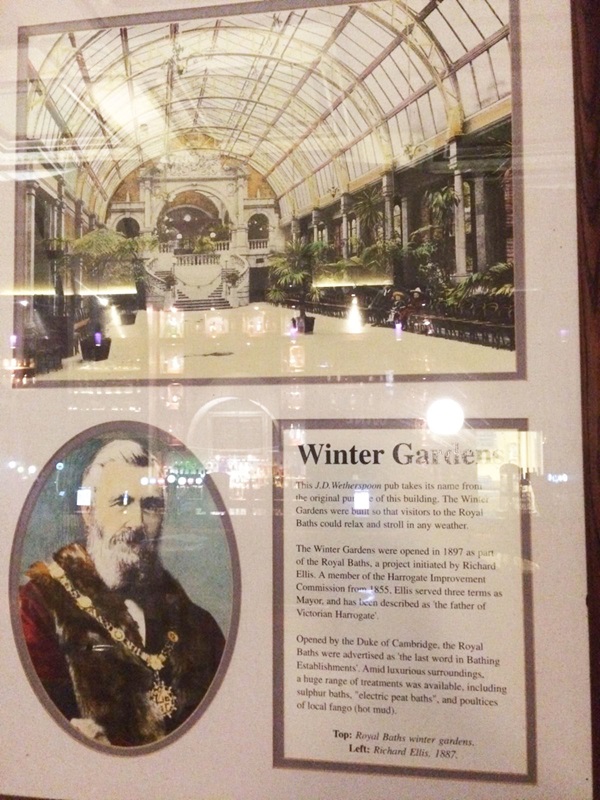

Prints and text about The Winter Gardens.

The text reads: This J D Wetherspoon pub takes its name from the original purpose of this building. The Winter Gardens were built so that visitors to the Royal Baths could relax and stroll in any weather.

The Winter Gardens were opened in 1897 as part of the Royal Baths, a project initiated by Richard Ellis. A member of the Harrogate Improvement Commission from 1855. Ellis served three terms as Mayor, and has been described as ‘the father of Victorian Harrogate’.

Opened by the Duke of Cambridge, the Royal Baths were advertised as ‘the last word in Bathing Establishments’. Amid luxurious surroundings, a huge range of treatments was available, including sulphur baths, electric peat baths, and poultices of local fango (hot mud).

Top: Royal Baths winter gardens

Left: Richard Ellis, 1887.

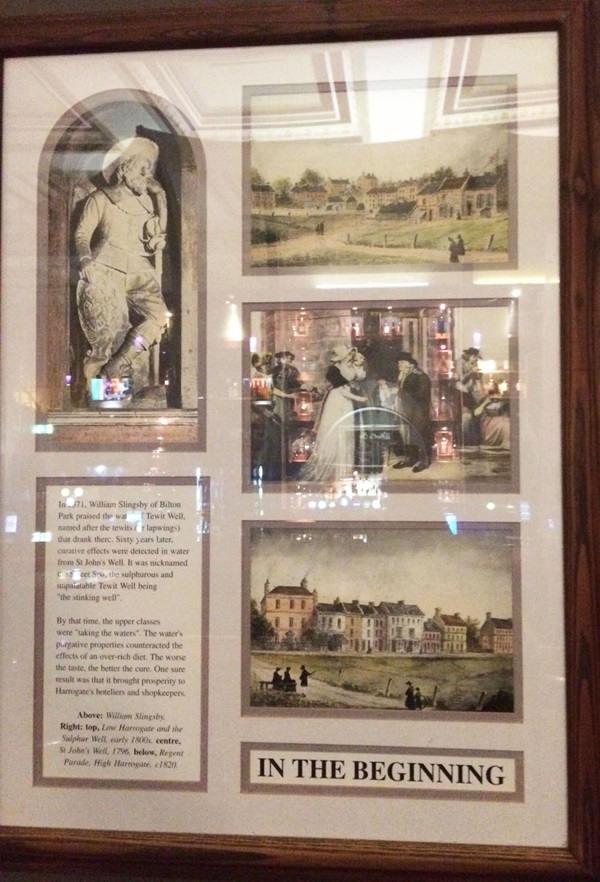

Illustrations and text about Tewit Well.

The text reads: In 1571, William Slingsby of Bilton Park praised the water of Tewit Well, named after the tewits (or lapwings) that drank there. Sixty years later, curative effects were detected in water from St John’s Well. It was nicknamed the Sweet Spa, the sulphurous and unpalatable Tewit Well being “the stinking well”.

By that time, the upper classes were “taking the waters”. The water’s purgative properties counteracted the effects of an over-rich diet. The worse the taste, the better the cure. One sure result was that it brought prosperity to Harrogate’s hoteliers and shopkeepers.

Above: William Slingsby

Right: top, Low Harrogate and the Sulphur Well, early 1800s, centre, St John’s Well, 1796, below, Regent Parade, High Harrogate, c1820.

Prints, illustrations and text about Agatha Christie’s disappearance.

The text reads: Harrogate was the scene of dramatic events in December 1926. The famous crime novelist Agatha Christie, who was thought to have been abducted or even dead, was found dancing the Charleston at the Old Swan, in Swan Road.

Her car had been discovered by a road near Guildford, and for a week police and volunteers had searched the Surry Downs for clues to her fate. Eleven days later, members of the hotel’s resident band recognised her from a widely distributed missing poster.

The explanation offered to the public was that Christie had briefly lost her memory after a car accident. Few believed this. Some suggested a nervous breakdown, while others thought the affair was a publicity stunt.

Her disappearance seems to have been a message to her husband, Colonel Archie Christie. The couple were divorced two years later.

Above: right, the Old Swan c1820 and c1950, left, Found! Agatha Christie leaves Harrogate

Right: The crime writer’s disappearance led to a national newspaper campaign to find her.

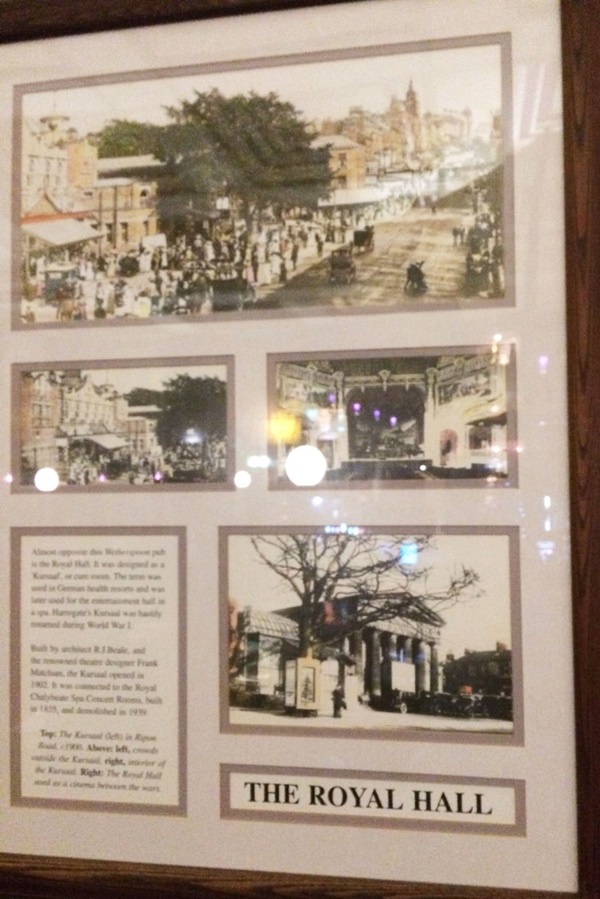

Illustrations and text about The Royal Hall.

The text reads: Almost opposite this Wetherspoon pub is the Royal Hall. It was designed as a Kursaal, or cure room. The term was used in German health resorts and was later used for the entertainment hall in a spa. Harrogate’s Kursaal was hastily renamed during World War I.

Built by architect RJ Beale, and the renowned theatre designer Frank Matcham, the Kursaal opened in 1902. It was connected to the Royal Chalybeate Spa Concert Rooms, built in 1825, and demolished in 1939.

Top: The Kursaal (left) in Ripon Road, c1900.

Above: left, crowds outside the Kursaal, right, interior of the Kursaal

Right: The Royal Hall used as a cinema between the wars.

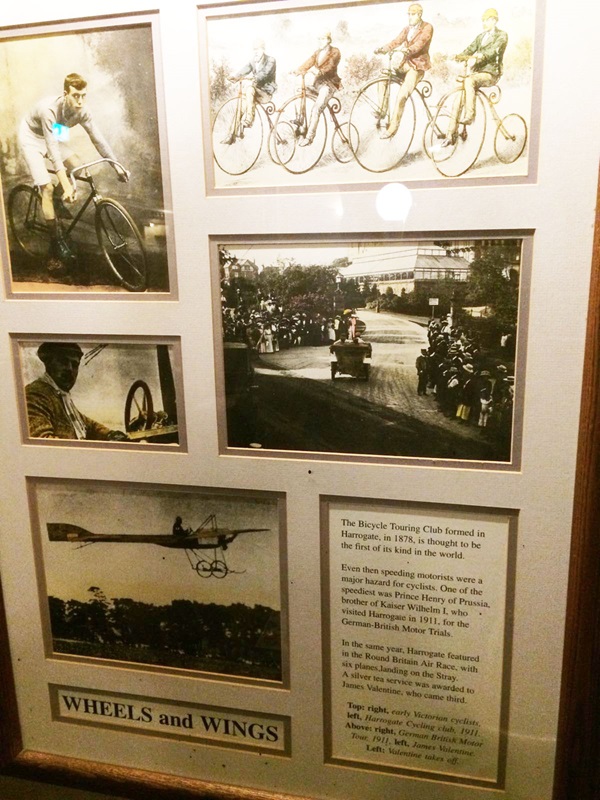

Prints, illustrations and text about the history of wheels and wings in Harrogate.

The text reads: The Bicycle Touring Club formed in Harrogate, in 1878, is thought to be the first of its kind in the world.

Even then speeding motorists were a major hazard for cyclists. One of the speediest was Prince Henry of Prussia, brother of Kaiser Wilhelm I, who visited Harrogate in 1911, for the German-British Motor Trials.

In the same year, Harrogate featured in the Round Britain Air Race, with six planes landing on the Stray. A silver tea service was awarded to James Valentine, who came third.

Top: right, early Victorian cyclists, left, Harrogate Cycling Club, 1911

Above: right, German British Motor Tour, 1911, left, James Valentine

Left: Valentine takes off.

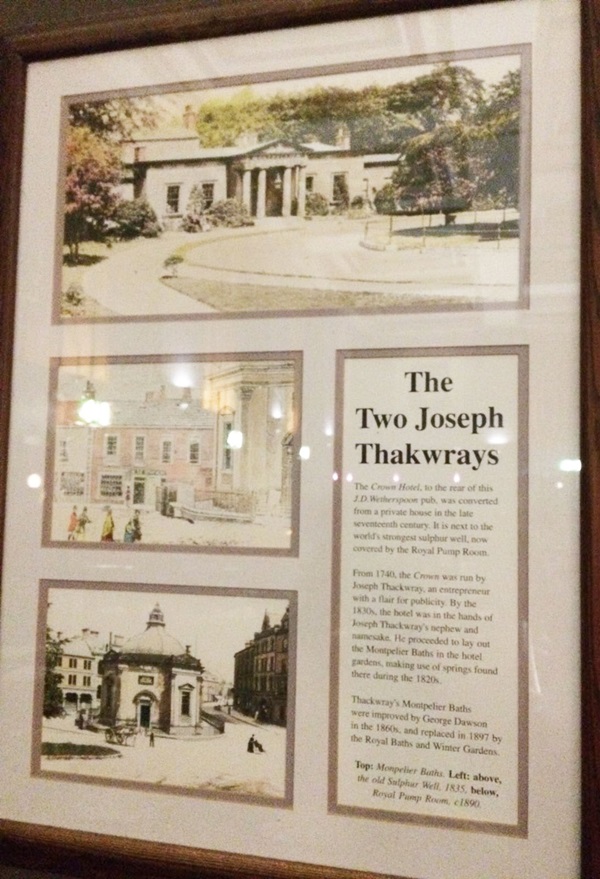

A print, illustrations and text about the Thackwrays.

The text reads: The Crown Hotel, to the rear of this J D Wetherspoon pub, was converted from a private house in the late seventeenth century. It is next to the world’s strongest sulphur well, now covered by the Royal Pump Room.

From 1740, the Crown was run by Joseph Thackwray, an entrepreneur with a flair for publicity. By the 1830s, the hotel was in the hands of Joseph Thackwray’s nephew and namesake. He proceeded to lay out the Montpelier Baths in the hotel gardens, making use of springs found there during the 1820s.

Thackwray’s Montpelier Baths were improved by George Dawson in the 1860s and replaced in 1897 by the Royal Baths and Winter Gardens.

Top: Montpelier Baths

Left: above, the old Sulphur Well, 1835, below, Royal Pump Room, c1890.

Internal photographs showing the original features of the Winter Gardens.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

Extract from Wetherspoon News Winter 2017.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk