Named after William Jameson, who laid out Fawcett Street and the surrounding roads, on behalf of the Fawcett family. Fawcett Street was originally one of Sunderland’s finest residential areas. Building work started in 1814, when the family instructed William Jameson to lay out the estate. By 1844, Fawcett Street was virtually complete, with imposing three- and four-storey houses.

Photographs and text about The William Jameson.

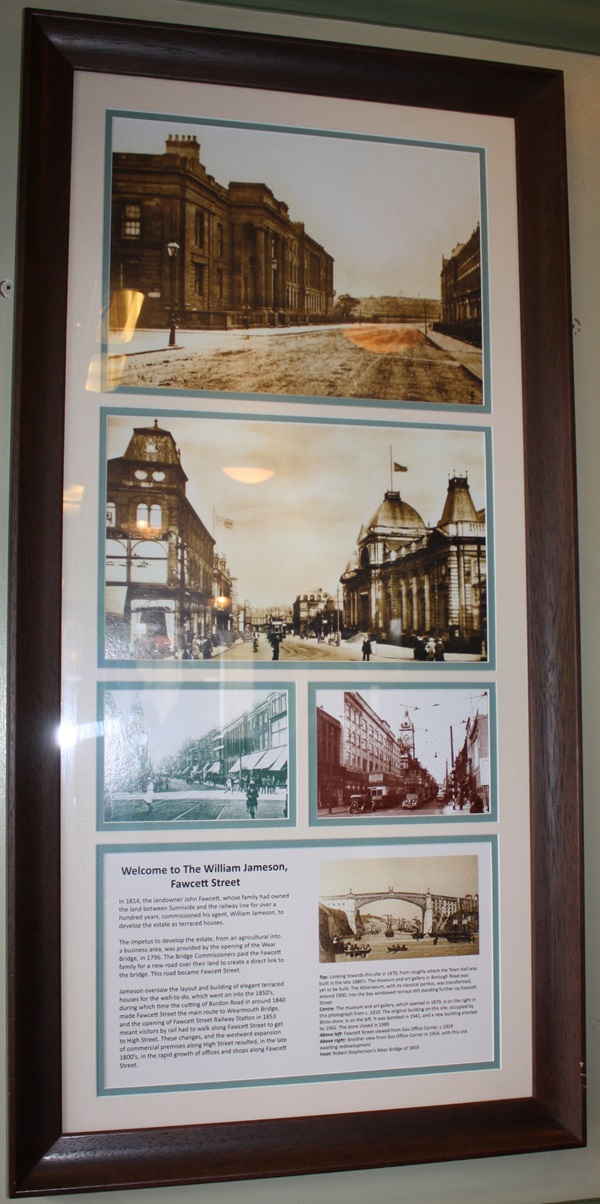

The text reads: In 1814, the landowner John Fawcett, whose family had owned the land between Sunniside and the railway line for over a hundred years, commissioned his agent, William Jameson, to develop the estate as terraced houses.

The impetus to develop the estate, from an agricultural into a business area, was provided by the opening of the Wear Bridge, in 1796. The Bridge Commissioners paid the Fawcett family for a new road over their land to create a direct link to the bridge. This road became Fawcett Street.

Jameson oversaw the layout and building of elegant terraced houses for the well-to-do, which went on into the 1850’s, during which time the cutting on Burdon Road in around 1840 made Fawcett Street the main route to Wearmouth Bridge, and the opening of Fawcett Street Railway Station in 1853 meant visitors by rail had to walk along Fawcett Street to get to High Street. These changes, and the westward expansion of commercial premises along High Street resulted, in the late 1800’s, in the rapid growth of offices and shops along Fawcett Street.

Top: Looking towards this site in 1870, from roughly where the Town Hall was built in the late 1880’s. The museum and art gallery in Borough Road was yet to be built. The Athenaeum, with its classical portico, was transformed, around 1900, into the bay windowed terrace still standing further up Fawcett Street.

Centre: The museum and art gallery, which opened in 1879, is on the right in this photograph from c.1910. The original building on this site, occupied by Binns store is on the left. It was bombed in 1941, and a new building erected by 1982. The store closed in 1989.

Above left: Fawcett Street viewed from Gas Office Corner, c.1919.

Above right: Another view from Gas Office Corner in 1954, with this site awaiting redevelopment.

Inset: Robert Stephenson’s Wear Bridge of 1859.

Illustrations and text about Samuel Plimsoll.

The text reads: Until the 1870s more people in Sunderland were employed as sailors than in any other work. Wages were low, the work hard and conditions poor.

Although the workers were often exploited by their bosses, they also had an ally in Samuel Plimsoll who set out to improve the sailor’s lot. His campaign followed his election to Parliament in 1868.

Much of the evidence he used to back up his fight came from the North East. Overloading was common and it became evident that one of those guilty of such practice was the Sunderland shipbuilder and shipowner James Laing.

Plimsoll’s struggle was a lengthy one, but he eventually succeeded when the Merchant Shipping Act was passed. This forced every owner to mark their ship with a circular disc, known as the Plimsoll Mark, with horizontal line drawn through its centre showing the level to which it may be loaded.

His campaign was supported by the National Amalgamated Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union of Great Britain and Ireland, the forerunner to the National Union of Seamen.

It was founded in Sunderland in 1897 by a local man, Joseph Havelock Wilson. He had first-hand knowledge of the conditions faced by sailors, as well as a desire to improve them.

Above: Samuel Plimsoll.

Prints and text about football in Sunderland.

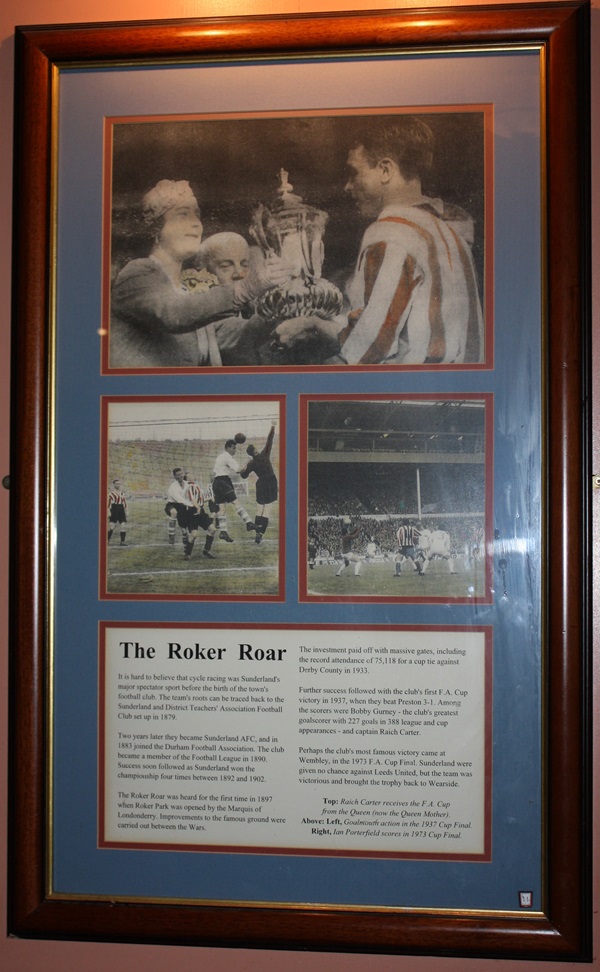

The text reads: It is hard to believe that cycle racing was Sunderland’s major spectator sport before the birth of the town’s football club. The team’s roots can be traced back to the Sunderland and District Teachers’ Association Football Club set up in 1879.

Two years later they became Sunderland AFC, and in 1883 joined the Durham Football Association. The club became a member of the Football League in 1890. Success soon followed as Sunderland won the championship four times between 1892 and 1902.

The Roker Roar was heard for the first time in 1897 when Roker Park was opened by the Marquis of Londonderry. Improvements to the famous ground were carried out between the Wars.

The investment paid off with massive gates, including the record attendance of 75,118 for a cup tie against Derby County in 1933.

Further success followed with the club’s first F.A. Cup victory in 1937, when they beat Preston 3-1. Amount the scorers were Bobby Gurney – the club’s greatest goal scorer with 227 goals in 388 league and cup appearances – and captain Raich Carter.

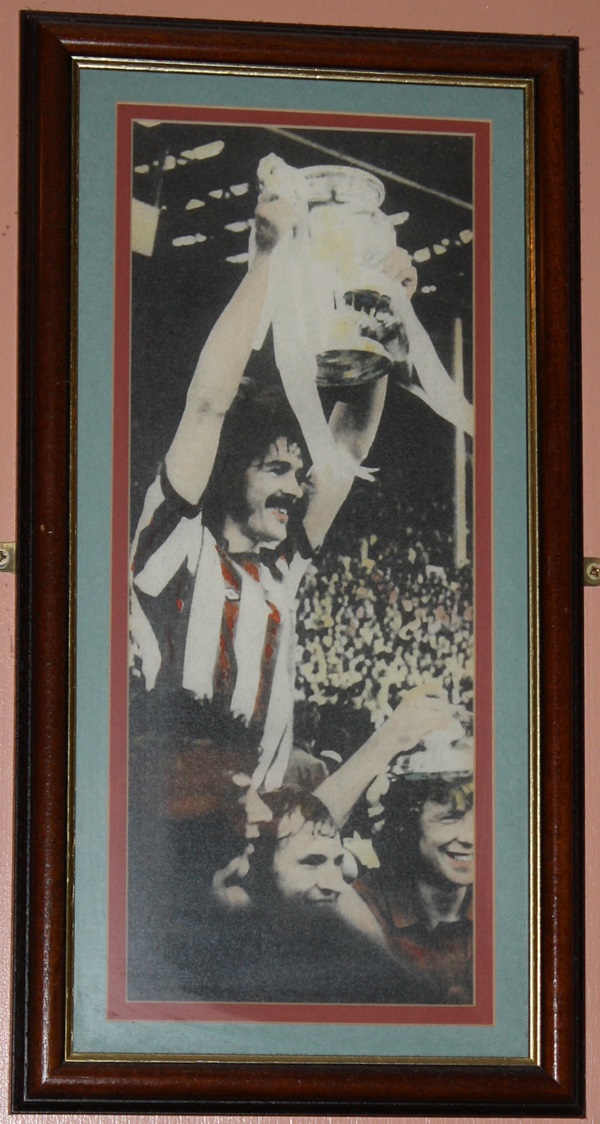

Perhaps the club’s most famous victory came at Wembley, in the 1973 F.A. Cup Final. Sunderland were given no chance against Leeds United, but the team was victorious and brought the trophy back to Wearside.

Top: Raich Carter receives the F.A. Cup from the Queen (now the Queen Mother)

Above: Left, Goalmouth action in the 1937 Cup Final

Right: Ian Porterfield scores in 1973 Cup Final.

A print of Raich Carter with the FA Cup, in 1937.

A print of Bobby Kerr raising the FA Cup, in 1973.

Text about theatres in Sunderland .

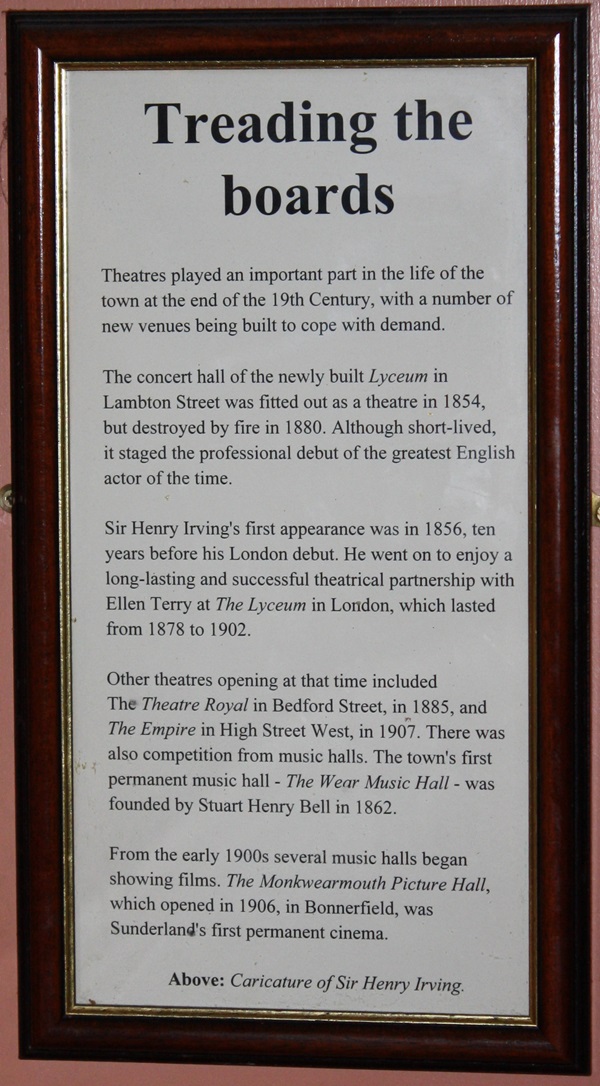

The text reads: Theatres played an important part in the life of the town at the end of the 19th Century, with a number of new venues being built to cope with demand.

The concert hall of the newly built Lyceum in Lambton Street was fitted out as a theatre in 1854, but destroyed by fire in 1880. Although short-lived, it staged the professional debut of the greatest English actor of the time.

Sir Henry Irving’s first appearance was in 1856, ten years before his London debut. He went on to enjoy a long-lasting and successful theatrical partnership with Ellen Terry at The Lyceum in London, which lasted from 1878 to 1902.

Other theatres opening at that time included The Theatre Royal in Bedford Street in 1885, and The Empire in High Street West, in 1907. There was also competition from music halls. The town’s first permanent music hall – The Wear Music Hall – was founded by Stuart Henry Bell in 1862.

From the early 1900s several music halls began showing films. The Monkwearmouth Picture Hall, which opened in 1906, in Bonnerfield, was Sunderland’s first permanent cinema.

Above: Caricature of Sir Henry Irving.

Text about famous figures in Sunderland.

The text reads: Some of the biggest names in show business have graced the stage at The Empire Theatre since Vesta Tilley began her long association with the venue by laying the foundation stone in September 1906. The most celebrated male impersonator of her day, she returned the following year for the opening night’s performance.

The early Empire was the home of twice nightly variety shows. Since then everyone from Harry Houdini to The Who have appeared there.

Laurel and Hardy played The Empire in 1952 and 1954. Tommy Steele made his professional debut there in 1956. When The Beatles performance (February 1963) was reviewed, a local newspaper critic described the Fab Four as “going nowhere” and “eminently forgettable”.

The venue has survived many changes of fashion and taste in the entertainment world over the years. It also got through World War Two without a scratch, although a massive bomb rocked the building after landing nearby.

As a precaution the original revolving steel globe carrying The Empire sign and a statue of Terpsichore, the Greek Goddess of Dance, were removed.

Above: Vesta Tilley.

Prints of the entertainment industry in Sunderland.

Top: Left, The Theatre Royal

Right, Interior of the Empire, 1907

Above: Left, Sir Henry Irving

Right, Vesta Tilley (in female attire)

Left, Harry Houdini

Right: Above, The Beatles

Below, The Who.

Illustrations and text about Wearmouth.

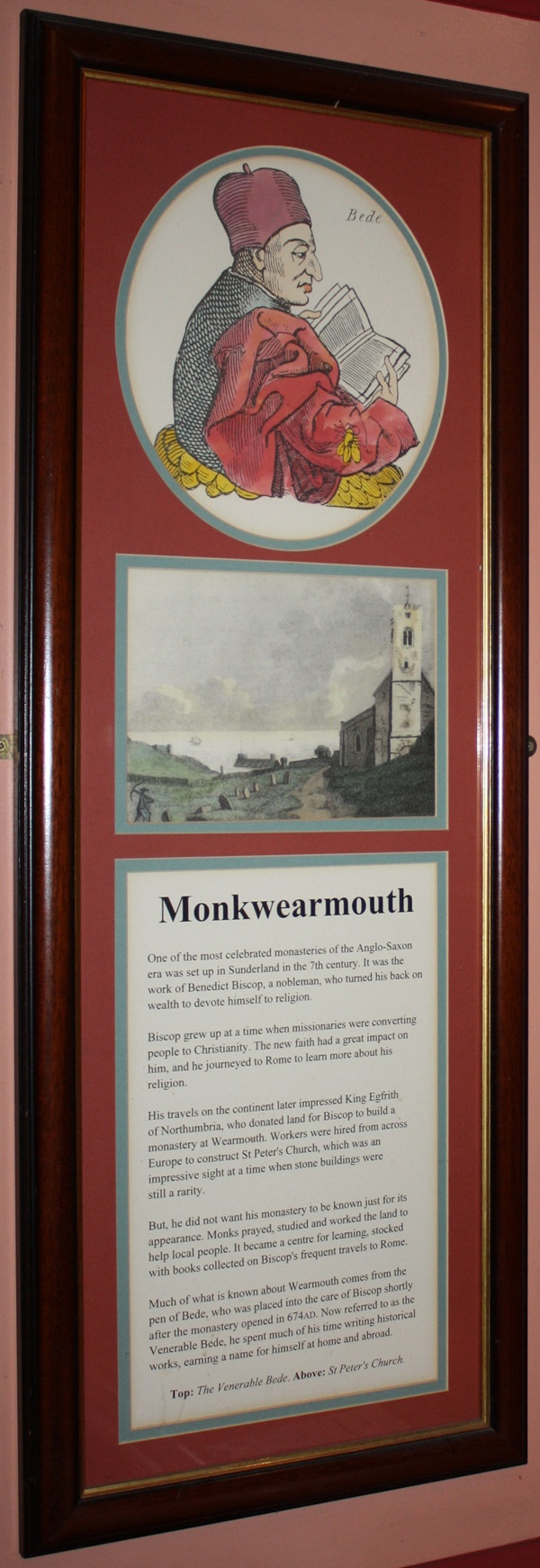

The text reads: One of the most celebrated monasteries of the Anglo-Saxon era was set up in Sunderland in the 7th century. It was the work of Benedict Biscop, a nobleman, who turned his back on wealth to devote himself to religion.

Biscop grew up at the time when missionaries were converting people to Christianity. The new faith had a great impact on him, and he journeyed to Rome to learn more about his religion.

His travels on the content later impressed King Egfrith of Northumbria, who donated land for Biscop to build a monastery at Wearmouth. Workers were hired from across Europe to construct St Peter’s Church, which was an impressive sight at a time when stone buildings were still a rarity.

But, he did not want his monastery to be known just for its appearance. Monks prayed, studied and worked the land to help local people. It became a centre for learning, stocked with books collected on Biscop's frequent travels to Rome.

Much of what is known about Wearmouth comes from the pen of Bede, who was placed into the care of Biscop shortly after the monastery opened in 674AD. Now referred to as the Venerable Bede, he spent much of his time writing historical works, earning a name for himself at home and abroad.

Top: The Venerable Bede

Above: St Peter’s Church.

Illustrations and text about John Wesley.

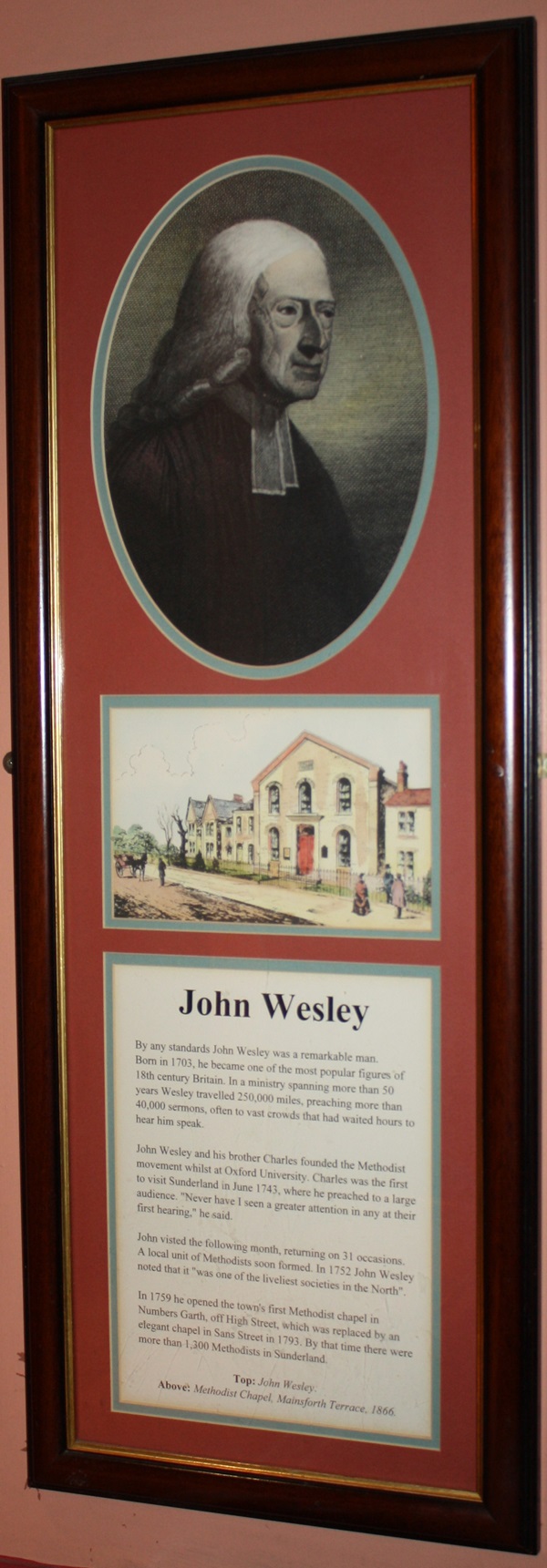

The text reads: By any standards John Wesley was a remarkable man. Born in 1703, he became one of the most popular figures of 18th century Britain. In a ministry spanning more than 50 years Wesley travelled 250,000 miles, preaching more than 40,000 sermons, often to vast crowds that had waited hours to hear him speak.

John Wesley and his brother Charles founded the Methodist movement whilst at Oxford University. Charles was the first to visit Sunderland in June 1743, where he preached to a large audience. “Never have I seen a greater attention in any at their first hearing,” he said.

John visited the following month, returning on 31 occasions. A local unit of Methodists soon formed. In 1752 John Wesley noted that if “was one of the liveliest societies in the North”.

In 1759 he opened the town’s first Methodist chapel in Numbers Garth, off High Street, which was replaced by an elegant chapel in Sans Street in 1793. By that time there were more than 1,300 Methodists in Sunderland.

Top: John Wesley

Above: Methodist Chapel, Mainsforth Terrace, 1866.

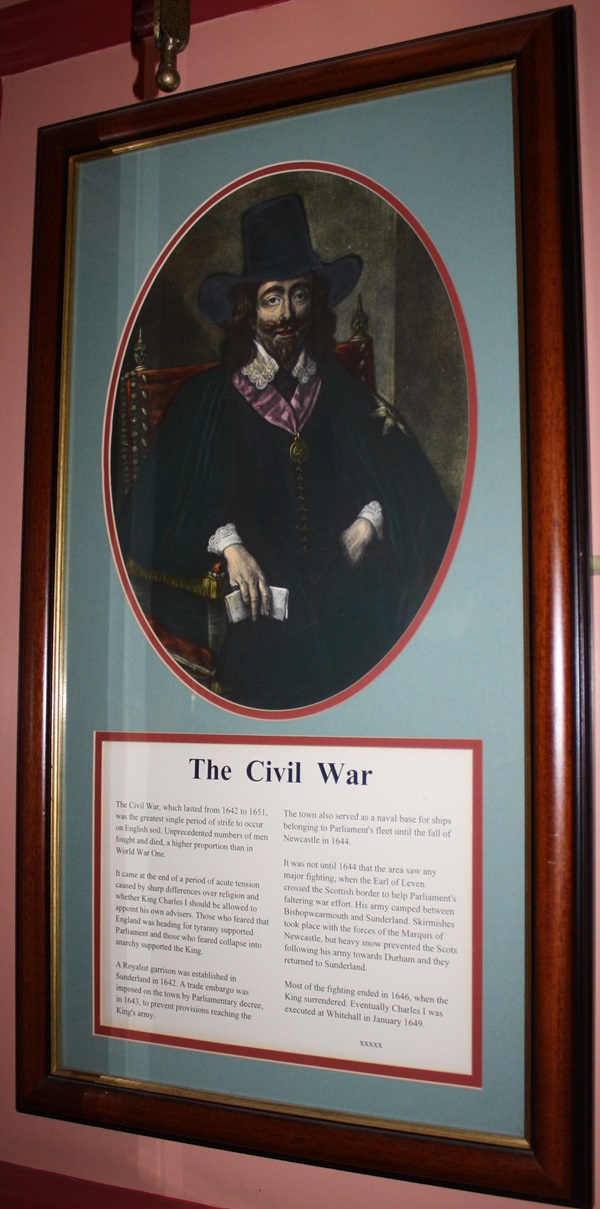

A print and text about The Civil War.

The text reads: The Civil War, which lasted from 1642 to 1651, was the greatest single period of strife to occur on English soil. Unprecedented number of men fought and died, a higher proportion than in World War One.

It came at the end of a period of acute tension caused by sharp differences over religion and whether King Charles I should be allowed to appoint his own advisers. Those who feared that England was heading for tyranny supported Parliament and those who feared collapse into anarchy supported the King.

A Royalist garrison was established in Sunderland in 1642. A trade embargo was imposed on the town by Parliamentary decree, in 1643, to prevent provisions reaching the King’s army.

The town also served as a naval base for ships belonging to Parliament’s fleet until the fall of Newcastle in 1644.

It was not until 1644 that the area saw any major fighting, when the Earl of Leven crossed the Scottish boarder to help Parliament’s faltering war effort. His army camped between Bishopwearmouth and Sunderland. Skirmishes took place with the forces of the Marquis of Newcastle, but heavy snow prevented the Scots following his army towards Durham and they returned to Sunderland.

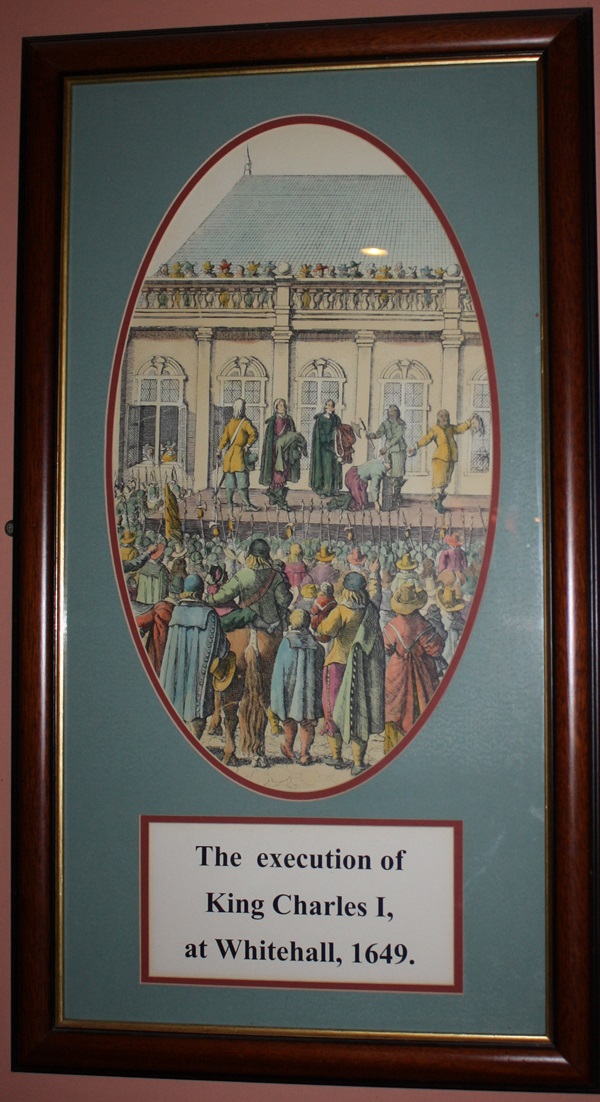

Most of the fighting ended in 1646, when the King surrendered. Eventually Charles I was executed at Whitehall in January 1649.

A print of the execution of King Charles I, at Whitehall, 1649.

A photograph and text about Binns Department Store.

The text reads: Binns Department Store (part of which was on this site) was one of Sunderland’s longest running stores. George Binns founded his drapery business in 1807, and the shop carrying his name finally closed its doors in January 1993. The business moved to Fawcett Street in 1884 where it occupied two houses. Expansion continued along Fawcett Street and, by 1921, Binns was trading on both sides of the street with a sales area measuring seven acres.

The Fawcett Street premises were lost in 1941 after a heavy bombing raid and, although temporary premises were found, rebuilding did not start until 1949. House of Fraser took over Binns in 1953 and the reconstructed store opened on the corner of Fawcett Street and Borough Road in 1962. The new site, which was linked by subway to the existing fashion building, had 25 acres of sales space on four floors.

A further facelift followed in 1972 and the store continued to trade for another 15 years. The furniture building closed in 1989, and unprofitable departments such as the food hall also shut. The end came 1993.

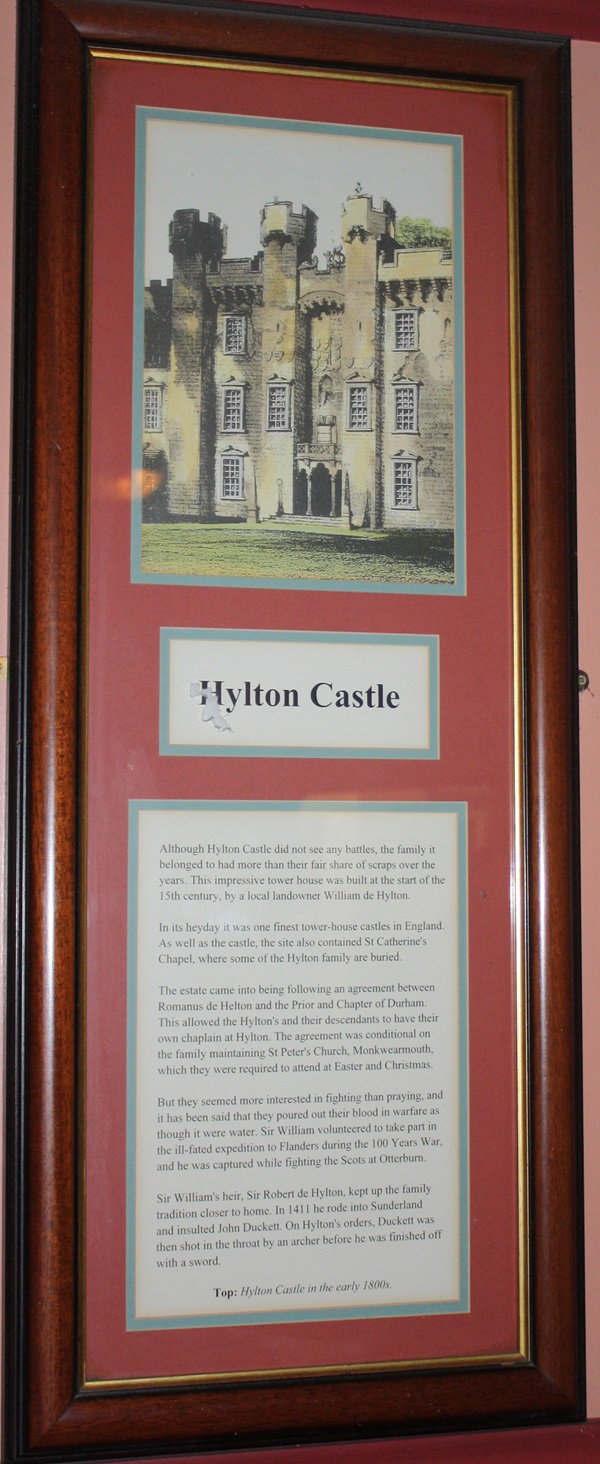

An illustration and text about Hylton Castle.

The text reads: Although Hylton Castle did not see any battles, the family it belonged to had more than their fair share of scraps over the years. The impressive tower house was built at the start of the 15th century, by a local landowner William de Hylton.

In its heyday it was one of the finest tower-house castles in England. As well as the castle, the site also contained St Catherine’s Chapel, where some of the Hylton family are buried.

The estate came into being following an agreement between Romanus de Helton and the Prior and Chapter of Durham. This allowed Hylton’s and their descendants to have their own chaplain at Hylton. The agreement was conditional on the family maintaining St Peter’s Church, Monkwearmouth, which they were required to attend at Easter and Christmas.

But they seemed more interested in fighting than praying, and it has been said that they poured out their blood in warfare as though it was water. Sir William volunteered to take part in the ill-fated expedition to Flanders during the 100 Years War, and he was captured while fighting the Scots at Otterburn.

Sir William’s heir, Sir Robert de Hylton, kept up the family tradition closer to home. In 1411 he rode into Sunderland and insulted John Duckett. On Hylton’s orders, Duckett was then shot in the throat by an archer before he was finished off with a sword.

Top: Hylton Castle in the early 1800s.

Illustrations, prints and text about the river and the docks.

The text reads: Sunderland’s standing as a port was badly affected by the opening of Seaham Harbour in 1831, along with similar developments on Teesside. Attempts to build docks suitable for the town and to cater for nearby pits were hit by arguments over which side of the river was best.

The North Dock, engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, opened in 1837 on land belonging to Sir Hedworth Williamson, one of County Durham’s MPs. But, it was never a success.

This was partly because Brunel’s bridge which would have bought coal from south of the river was never built. The Dock became known as ‘Sir Hedworth’s bathtub’.

The South Dock, which opened in 1850, also had political connections.

When George Hudson was elected as one of the town’s MPs it was on the understanding that he would use his influence to secure the necessary funding. His success was witnessed by 50,000 people at its opening.

Development of the seafront continued with Hendon Dock opening in 1868 and at Roker Pier with its 2,800 foot long breakwater and lighthouse, which opened in 1903.

Work on a similar southern breakwater began in 1893, but the project was never completed.

The port continued to thrive. During the 2nd World War it was used to handle war materials and US Army stores. Air raids caused some damage and mines were laid off its entrance by enemy aircraft but, on the whole, the supplies got through.

Top: Left, Opening of the docks at Sunderland, 1850

Centre, Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Right, The first shipment of coals at the new docks, 1850

Right: Warehouses, South Dock

Below: Left, The lighthouse on the South Pier

Right, view of Sunderland from the pier.

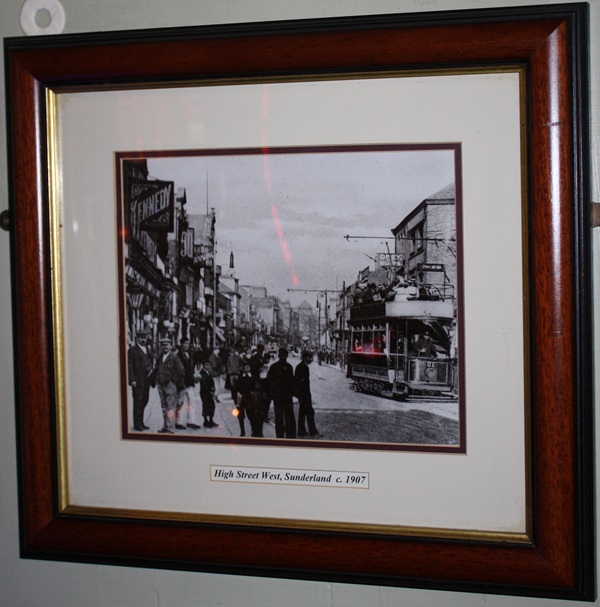

A photograph of High West Street, Sunderland c1907.

A photograph of High Street, Sunderland c1964.

A photograph of The Pontoon, Sunderland c1908.

A photograph of Roker Lower Promenade c1910.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk