Built as the Bell Inn, in the first half of the 19th century, this public house closed in the late 20th century. It is now this Wetherspoon pub.

Prints and text about the area’s metal industries.

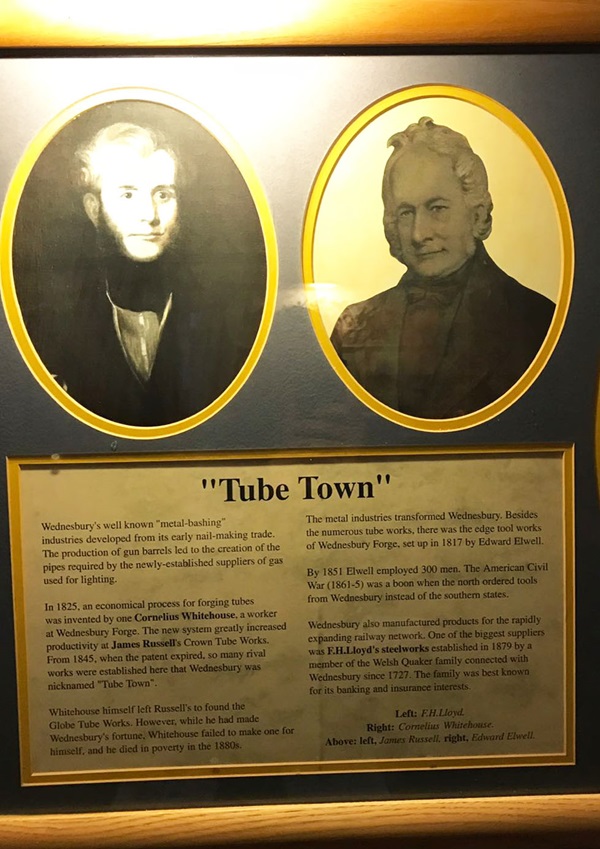

The text reads: Wednesbury’s well-known ‘metal bashing’ industries developed from its early nail-making trade. The production of gun barrels led to the creation of the pipes required by the newly established suppliers of gas used for lighting.

In 1825, an economical process for forging tubes was invented by one Cornelius Whitehouse, a worker at Wednesbury Forge. The new system greatly increased productivity at James Russell’s Crown Tube Works. From 1845, when the patent expired, so many rival works were established here that Wednesbury was nicknamed ‘Tube Town’.

Whitehouse himself left Russell’s to found the Globe Tube Works. However, while he had made Wednesbury’s fortune, Whitehouse failed to make one for himself, and he died in poverty in the 1880s.

The metal industries transformed Wednesbury. Besides the numerous tube works, there was the edge tool works of Wednesbury Forge, set up in 1817 by Edward Elwell.

In 1851 Elwell employed 300 men. The American Civil War (1861-5) was a boon when the north ordered tools from Wednesbury instead of the southern states.

Wednesbury also manufactured products for the rapidly expanding railway networks. One of the biggest suppliers was FH Lloyds steelworks established in 1879 by a member of the Welsh Quaker family connected with Wednesbury since 1727. The family was best known for its banking and insurance interests.

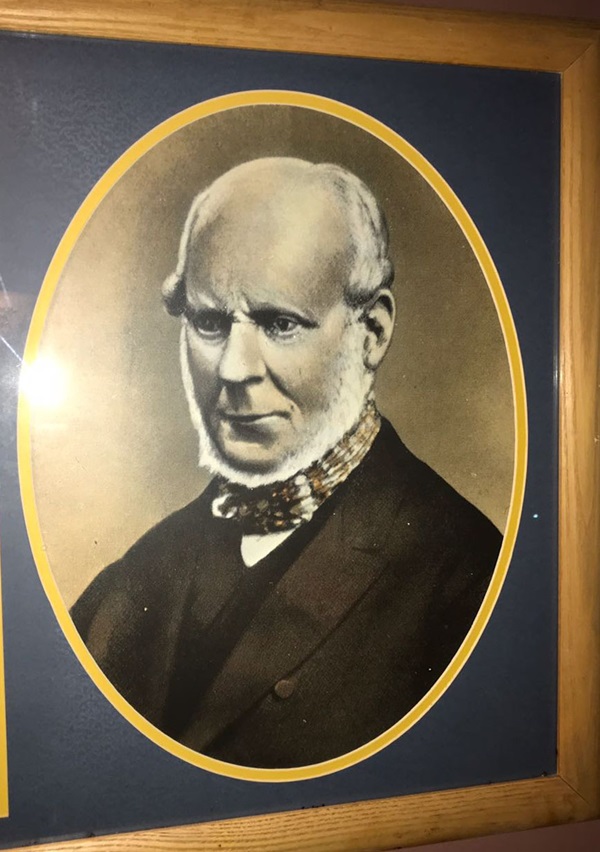

Left: FH Lloyd

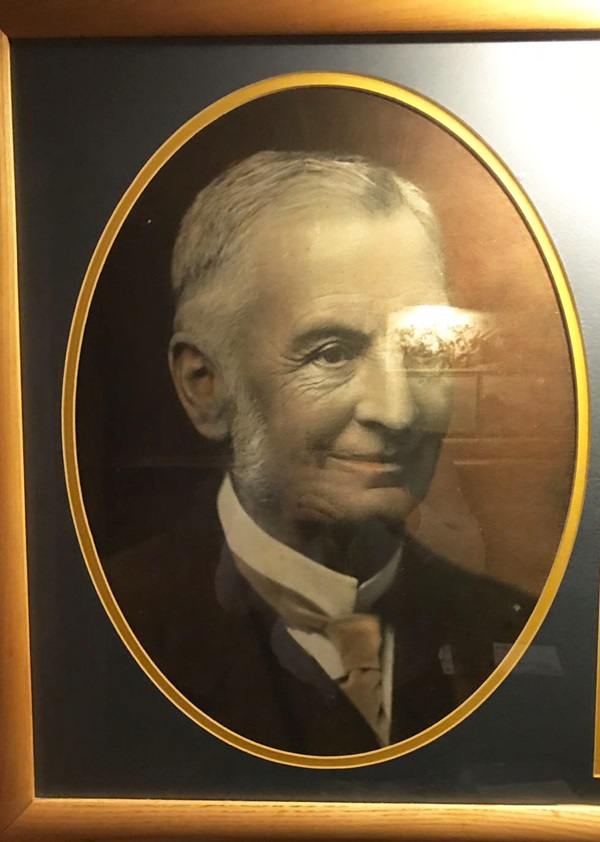

Right: Cornelius Whitehouse

Above: left, James Russell, right, Edward Elwell.

Illustrations and text about the history of Wednesbury.

The text reads: Wednesbury is one of the few places in England to be named after the Saxon god Woden. The name well may derive from a temple on the hill where St Bartholomew’s Church now stands.

Before Woden’s temple there was an Iron Age fort on Church Hill. This accounts for the ‘bury’ part in the name, which means a ‘defended settlement’. In the early 900s, King Alfred’s daughter Ethelflaed, ruler of Mercia, re-fortified ‘Wodensbeorg’ as it was on the frontier where the English faced the Danes.

With the unification of England, Wednesbury lost much of its former importance and reverted to a largely agricultural settlement. There was also the mining of shallow coal-deposits to provide fuel for local nail-makers.

The son of one nail-maker left his origins far behind, rising to the grand office of Secretary of State and a Knight of the Garter. William Paget, born in Wednesbury in 1505, was also one of the executors of the will of King Henry VIII.

Paget managed the remarkable feat of keeping his post and his head during the reigns of two of Henry’s children, Edward VI, and Mary I. However he retired when the third, Elizabeth I, came to the throne. Raised to the peerage in 1549 as Baron Paget, his descendants were the Marquises of Anglesey.

Above: centre, Woden, left, William Paget

Right: top, St Bartholomew’s Church, centre, Wednesbury Manor House, 1897, below, Market Cross, demolished 1824.

Illustrations and text about transport in the area.

The text reads: The appalling state of the country’s roads improved in the 18th century with the setting up of Turnpike Trusts. The road through Wednesbury was turnpiked in 1757, and improved by Thomas Telford, in 1826. Wednesbury was linked to nearby towns and the major cities by mail-coach services from coaching inns such as the Turk’s Head and the Red Lion Hotel.

Heavy goods were still difficult and expensive to transport until the coming of the canals. The Wednesbury Old Canal was dug in 1769 providing a cheaper means of carrying the town’s coal to Birmingham. The Walsall Canal followed in 1783. The Tame Valley Canal of 1844 was one of the last to open. By then competition from the railways had begun.

The Grand Junction Railway Company’s line, built in 1837, skirted Wednesbury and had a station at Bescot. The London & North Western and Great Western lines followed in the 1850s. They provided a great stimulus to the town’s industry. Rivalry with the canal companies lowered the cost of transporting metal goods, and local heavy industry prospered by supplying the railway companies with metal-work.

Right: Thomas Telford

Above: Elwell’s pool and wooden railway viaduct, 1859

Left: Upper High Street, 1900, part of the coaching road to Holyhead until Telford’s improvements of 1826.

Illustrations, prints and text about the Civil War.

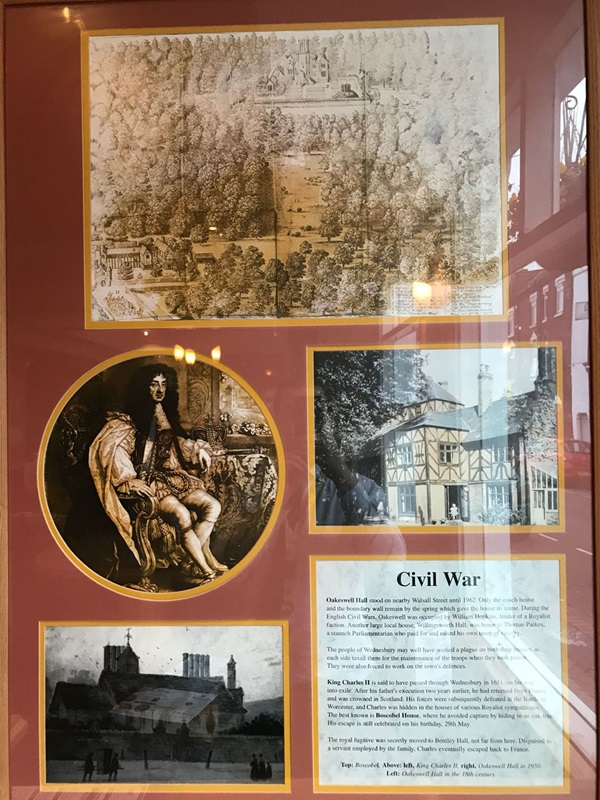

The text reads: Oakeswell Hall stood on nearby Walsall Street until 1962. Only the coach house and the boundary wall remain by the spring which gave the house its name. During the English civil wars, Oakeswell was occupied by William Hopkins, leader of a Royalist faction. Another large local house, Willingsworth Hall, was home to Thomas Parkes, a staunch Parliamentarian who paid for and raised his own troop of cavalry.

The people of Wednesbury may well have wished a plague on both their houses, as each side taxed them for the maintenance of the troops when they took power. They were also forced to work on the town’s defences.

King Charles II is said to have passed through Wednesbury in 1651, on his way into exile. After his father’s execution two years earlier, he had returned from France and was crowned in Scotland. His forces were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Worcester, and Charles was hidden in the houses of various Royalist sympathisers. The best known is Boscobel House, where he avoided capture by hiding in an oak tree. His escape is still celebrated on his birthday. 29 May.

The royal fugitive was secretly moved to Bentley Hall, not far from here. Disguised as a servant employed by the family, Charles eventually escaped back to France.

Top: Boscobel

Above: left, King Charles II, right, Oakeswell Hall in 1950

Left: Oakeswell Hall in the 18th century.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk