The dragon dance is highly popular and has a very long tradition, dating from ancient China. The dance is usually performed on big occasions, especially during Chinese new-year celebrations. Dragons are an important part of Chinese culture, seen as a symbol of good fortune, with dragon motifs occurring frequently in Chinese art. Dragons are also celebrated in events such as the dragon boat festival.

Framed traditional Chinese illustrations and text about The Dragon Inn.

The text reads: During the 1960s several Chinese businesses and social clubs emerged in the Hurst Street area, which later became Birmingham’s Chinese Quarter. The Arcadian Centre is at the heart of Chinatown and is the focal point of the Chinese New Year celebrations.

Known in Chian as the Spring Festival, this is the oldest and most important celebration in the Chinese calendar. The date of the holiday is determined by the lunar/solar calendar and varies from late January to mid-February.

The Dragon Dance is a highly popular part of the New Year celebrations, and has a long tradition dating back to the days of ancient China. Dragons are an important part of Chinese culture, and are seen as a symbol of good fortune.

Top: An Imperial Dragon, from a mandarin robe of the Ch’ing dynasty. The Imperial dragon had five claws, and if a commoner drew a dragon with five claws, rather than the common four, they were sentenced to death.

Left: The Lantern Festival, one of the New Year festivals, in a Chinese home.

A framed illustration of an Imperial Dragon, from a mandarin robe of the Ch’ing Dynasty.

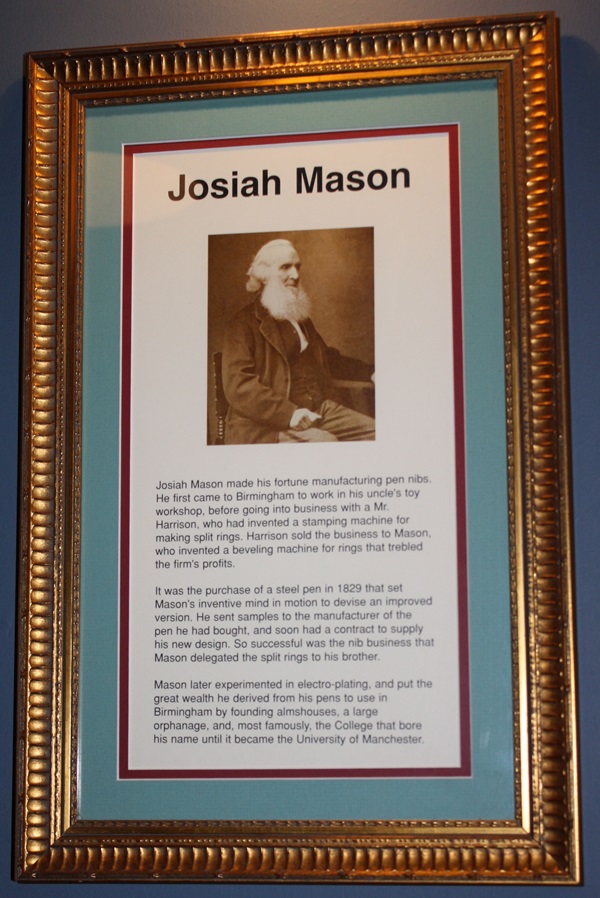

A framed photograph and text about Josiah Mason.

The text reads: Josiah Mason made his fortune manufacturing pen nibs. He first came to Birmingham to work in his uncle’s toy workshop, before going into business with a Mr. Harrison, who had invented a stamping machine for making split rings. Harrison sold the business to Mason, who invented a bevelling machine for rings that trebled the firm’s profits.

It was the purchase of a steel pen in 1829 that set Mason’s inventive mind in motion to devise an improved version. He sent samples to the manufacturer of the pen he had bought, and soon had a contract to supply his new design. So successful was the nib business that Mason delegated the split rings to his brother.

Mason later experimented in electro-plating, and put the great wealth he derived from his pens to use in Birmingham by founding almshouses, a large orphanage, and, most famously, the College that bore his name until it became the University of Manchester.

Framed photographs, drawings and text recounting the life and work of businessman Matthew Boulton.

The text reads: Matthew Boulton was Birmingham’s most prominent citizen in the 18th century. The son of a Birmingham silversmith and toymaker, he extended the business by building a manufactory on an area of barren heath at Soho in 1762, and from there set about revolutionizing industrial production. One of the first Birmingham townsmen to achieve an international reputation, he raised the profile of the town and of its products throughout the world. In combination with James Watt he developed the steam engine, of all factors the most fundamental in the growth of factory production in the Industrial Revolution.

Top: Matthew Boulton

Above: Soho Manufactory, c.1781

Left: Matthew Boulton, 1792

Framed photographs, drawings and text recounting the life of Thomas Attwood.

The text reads: Nearby Attwood House – at the junction of Smallbrook Queensway and New Street – recalls the 19th century Birmingham politician who was once dubbed “the most popular man in England”. Thomas Attwood led the campaign for Birmingham to have a voice in Parliament. In the early 19th century Birmingham was one of the biggest towns in England but did not have its own Member of Parliament. “King Towm” was later elected as one of the town’s two MPs, serving for seven years until he was forced to retire through ill-health.

Top: Thomas Attwood

Above: The gathering at Newhall Hill in 1832, addressed by Attwood, to demand representation

Right: Statue of Attwood erected in New Street.

Framed drawings and text recounting the history of the site of The Bull Ring Market.

The text reads: In the Doomsday Book, compiled for William the Conqueror, in 1086, Birmingham was a village valued at only £1. Its development began when Peter de Bermingham obtained a market was situated in the Bull Ring area, where traders gathered around the Market Cross. It was replaced in the 1700s by a two-storey hall, called Old Cross, which was Birmingham’s first venue for public meetings. In 1809, Britain’s first statue of Lord Nelson was unveiled on the site of the Old Cross, and remained there until the 1950s. The village pump was also sited in the Bull Ring, which has since been comprehensively redeveloped.

Top: The Bull Ring, c.1750

Centre: The same view in 1812

Above: The market in full swing, c.1820

Far right: top, the Bull Ring . c.1835, with the Market Hall on the right

centre, the Market Hall

below left, inside the Market Hall

below right, the old Market Cross.

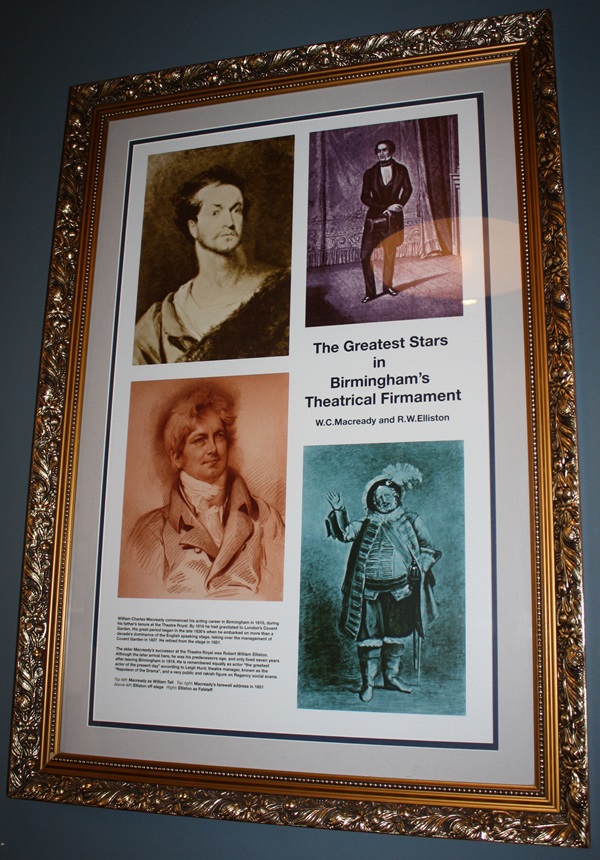

Framed drawings and text about William Charles Macready and Robert William Elliston.

The text reads: William Charles Macready commenced his acting career in Birmingham in 1810, during his father’s tenure at the Theatre Royal. By 1816 he had gravitated to London’s Covent Garden. His great period began in the late 1830’s when he embarked on more than a decade’s dominance of the English speaking stage, taking over the management of Covent Garden in 1837. He retired from the stage in 1851.

The elder Macready’s successor at the Theatre Royal was Robert William Elliston. Although the later arrival here, he was his predecessors age, and only lived seven years after leaving Birmingham in 1819. He is remembered equally as actor “the greatest actor of the present day” according to Leigh Hunt; theatre manager, known as the “Napoleon of the Drama”, and a very public and rakish figure on Regency social scene.

Top left: Macready as William Tell

Top right: Macready’s farewell address in 1851

Above left: Elliston off stage

Right: Elliston as Falstaff.

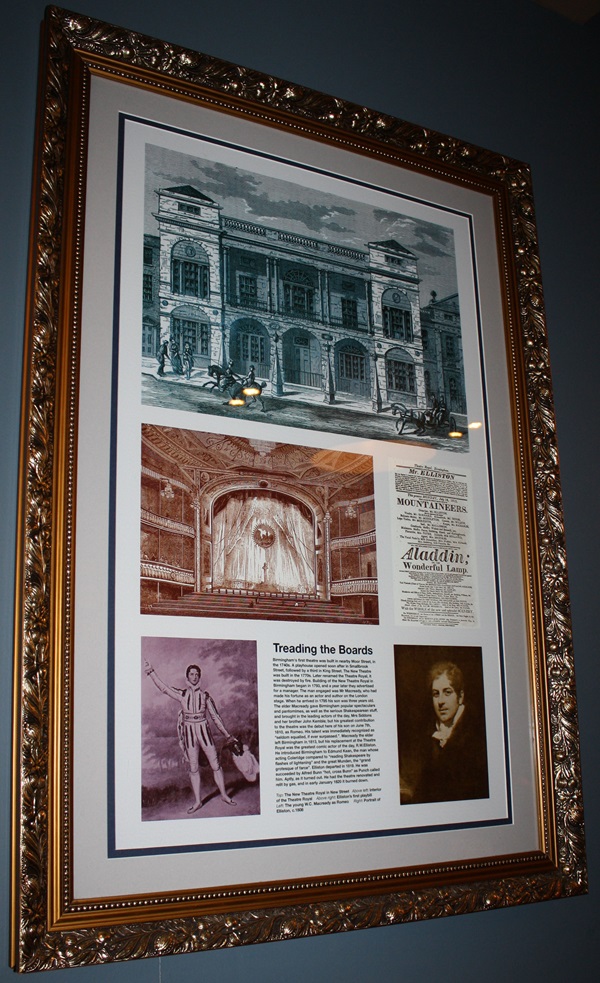

Framed drawings and text about The New Theatre Royal, in New Street, and of William Charles Macready and Robert William Elliston.

The text reads: Birmingham’s first theatre was built in nearby Moor Street, in the 1740s. A playhouse opened soon after in Smallbrook Street, followed by a third in King Street. The New Theatre was built in the 1770s. Later renamed the Theatre Royal, it was destroyed by fire. Building of the New Theatre Royal in Birmingham began in 1793, and a year later they advertised for a manager. The man engaged was Macready, who had made his fortune as an actor and author on the London stage. When he arrived in 1795 his son was three years old. The elder Macready gave Birmingham popular spectaculars and pantomimes, as well as the serious Shakespearean stuff, and brought in the leading actors of the day, Mrs Siddons and her brother John Kemble; but his greatest contribution to the theatre was the debut here of his son on June 7th, 1810, as Romeo. His talent was immediately recognized as “seldom equaled, if ever surpassed”. Macready the elder left Birmingham in 1813, but his replacement at the Theatre Royal was the greatest comic actor of the day, R.W. Elliston. He introduced Birmingham to Edmund Kean, the man whose acting Coleridge compared to “reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning” and the great Munden, the “grand grotesque of farce”. Elliston departed in 1819. He was succeeded by Alfred Bunn “hot, cross Bunn” as Punch called him. Aptly, as it turned out. He had the theatre renovated and relit by gas, and in early January 1820 it burned down.

Top: The New Theatre in New Street

Above left: Interior of The Theatre Royal

Above right: Elliston’s first playbill

Left: The young W.C. Macready as Romeo

Right: Portrait of Elliston, c.1808.

A sculpture entitled Draco, by George and Elsie McGill, October 2007.

An artwork by artist Jo Craig entitled Golden Dawn, October 2007.

One of The Dragon Inn’s three entrances, on Hurst Street.

An entrance to The Dragon Inn, found on Hurst Walk.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk