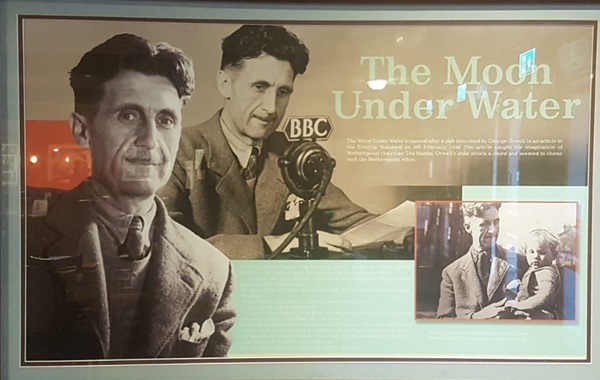

The author George Orwell wrote an article in the London Evening Standard about his favourite fictional pub which he called The Moon Under Water. When Wetherspoon’s chairman, Tim Martin, had around seven pubs in London, a journalist visited one of them and told Tim he liked the pub and that it was similar to the pub envisaged by George Orwell – in essence, a pub with a good atmosphere, good real ales, food and no music. Tim decided that it was a great name for a pub; in the following years, several were given this name.

Photographs and text about George Orwell.

The text reads: The Moon Under Water is named after a pub described by George Orwell in an article in the Evening Standard on 9 February, 1914. The article caught the imagination of Wetherspoon chairman Tim Martin. Orwell’s ideal struck a chord and seemed to chine with the Wetherspoon ethos.

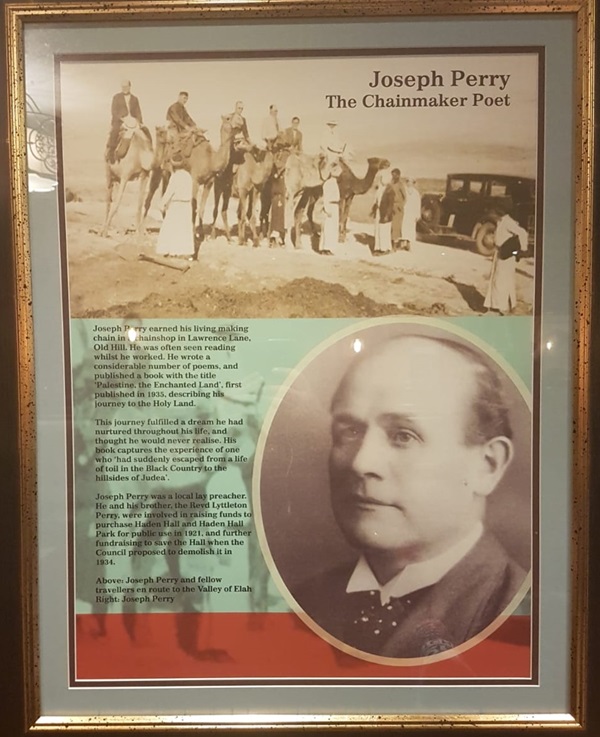

Photographs and text about Joseph Perry.

The text reads: Joseph Perry earned his living making chain in chain shop in Lawrence Lane, Old Hill. He was often seen reading whilst he worked. He wrote a considerable number of poems, and published a book with the title ‘Palestine, the Enchanted Land’, first published in 1935, describing his journey to the Holy Land.

This journey fulfilled a dream he had nurtured throughout his life, and thought he would never realise. His book captures the experience of one who ‘had suddenly escaped from a life of toil in the Black Country to the hillsides of Judea’.

Joseph Perry was a local lay preacher. He and his brother, the Revd Lyttleton Perry, were involved in raising funds to purchase Harden Hall and Harden Hall Park for public use in 1921, and further fundraising to save the Hall when the Council proposed to demolish it in 1934.

Above: Joseph Perry and fellow travellers en route to the Valley of Elah

Right: Joseph Perry.

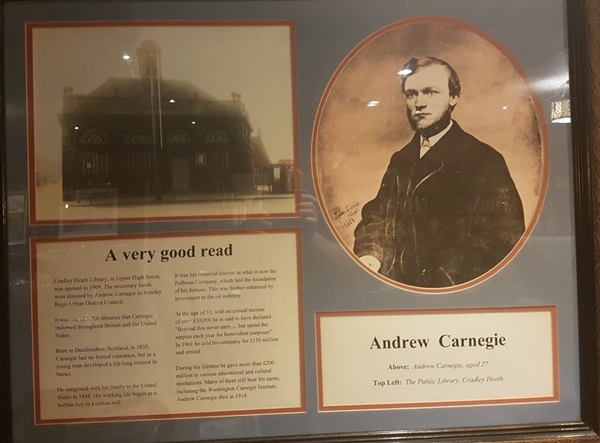

Prints and text about Andrew Carnegie.

The text reads: Cradley Heath Library, in Upper High Street, was opened in 1909. The necessary funds were donated by Andrew Carnegie to Rowley Regis Urban District Council.

It was one of 1,700 libraries that Carnegie endowed throughout Britain and the United States.

Born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835, Carnegie had no formal education, but as a young man developed a lifelong interest in books.

He emigrated with his family to the united States in 1848. His working life began as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill.

It was his financial interest in what is now the Pullman Company, which laid the foundation of his fortune. This was further enhanced by investment in the oil industry.

At the age of 33, with an annual income of over £30,000 he is said to have declared: “Beyond this never earn… but spend the surplus each year for benevolent purposes”. In 1901 he sold his company for £150 million and retired.

During his lifetime he gave more than £200 million to various educational and cultural institutions. Many of them still bear his name, including the Washington Carnegie Institute. Andrew Carnegie died in 1918.

Above: Andrew Carnegie, aged 27

Top left: The Public Library, Cradley Heath.

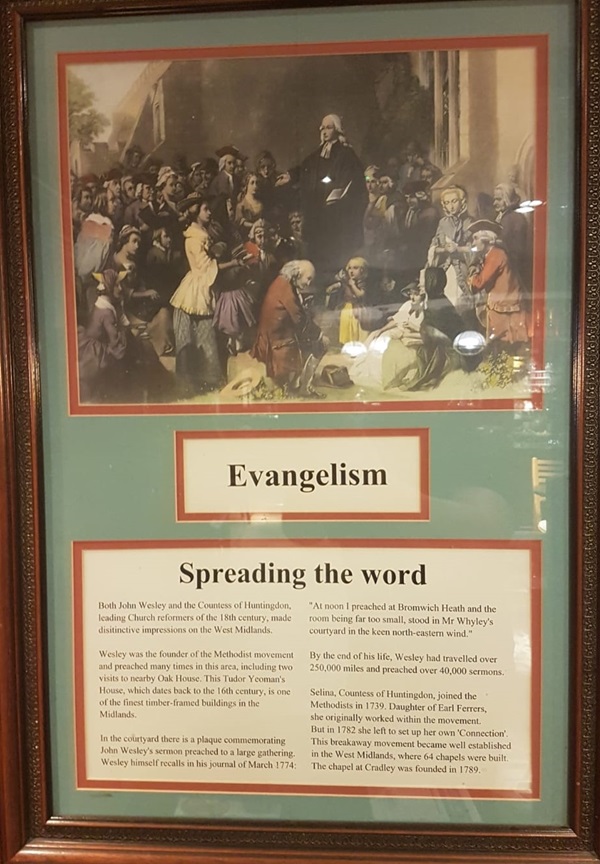

A print and text about Evangelism.

The text reads: Both John Wesley and the Countess of Huntingdon, leading Church reformers of the 18th century, made distinctive impressions on the West Midlands.

Wesley was the founder of the Methodist movement and preached many time in this areas, including two visits to nearby Oak House. This Tudor Yeoman’s House, which dates back to the 16th century, is one of the finest timber-framed buildings in the Midlands.

In the courtyard there is a plaque commemorating John Wesley’s sermon preached to a large gathering Wesley himself recalls in his journal of March 1774:

“At noon I preached at Bromwich Heath and the room being far too small, stood in Mr Whyley’s courtyard in the keen north-eastern wind.”

By the end of his life, Wesley had travelled over 250,000 miles and preached over 40,000 sermons.

Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, joined the Methodists in 1739. Daughter of Earl Ferrers, she originally worked within the movement. But in 1782 she left to set up her own ‘connection’. This breakaway movement became well established in the West Midlands, where 64 chapels were built. The chapel at Cradley was founded in 1789.

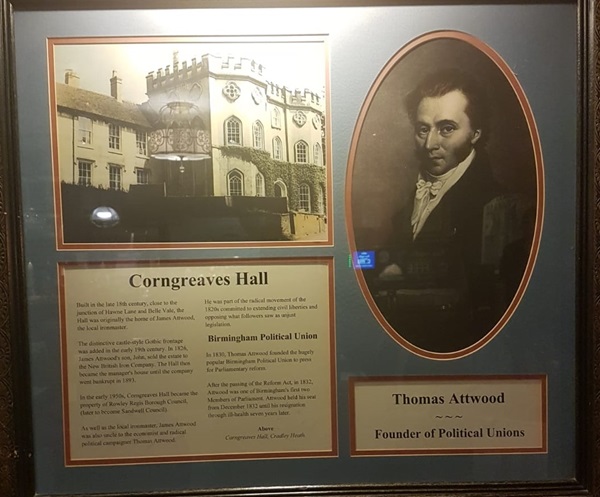

Prints and text about Corngreaves Hall and Thomas Attwood.

The text reads: Built in the late 18th century, close to the junction of Hawne Lane and Belle Vale, the Hall was originally the home of James Attwood, the local ironmaster.

The distinctive castle-style Gothic frontage was added in the early 19th century. In 1826, James Attwood’s son, John, sold the estate to the New British Iron Company. The Hall then became the manager’s house until the company went bankrupt in 1893.

In the early 1950s, Corngreaves Hall became the property of Rowley Regis Borough Council (later to become Sandwell Council).

As well as the local ironmaster, James Attwood was also uncle to the economist and radical political campaigner Thomas Attwood.

He was part of the radical movement of the 1820s committed to extending civil liberties and opposing what followers saw as unjust legislation.

In 1830, Thomas Attwood founded the hugely popular Birmingham Political Union to press for Parliamentary reform.

After the passing of the Reform Act, in 1832, Attwood was one of Birmingham’s first two Members of Parliament. Attwood held his seat from December 1832 until his resignation through ill-health seven years later.

Above: Corngreaves Hall, Cradley Heath.

A photograph of the River Stour flood, Cradley Heath, c1910.

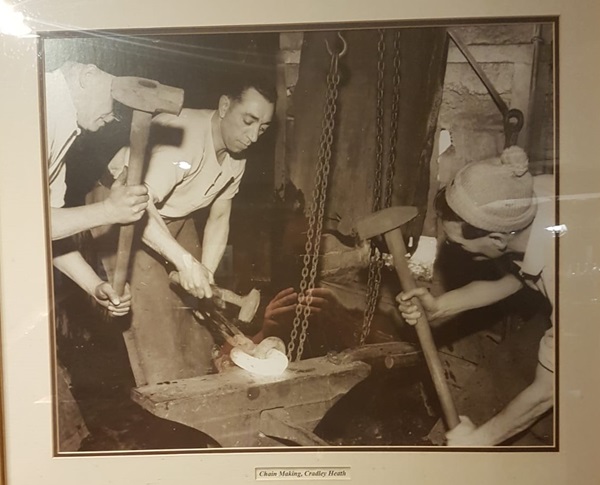

A photograph of chain making, Cradley Heath.

A photograph of chain making, Cradley Heath.

Photographs of chain making, Cradley Heath.

An original chain and fitting system.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk