The Corporation Street area was laid out from 1878. Seven years later, Lewis’s department store opened at the junction with Bull Street, trading here until 1991. The ground floor of this huge, imposing, square building is now this Wetherspoon pub.

A framed passage recounting the history of The Square Peg.

The text reads: The name of this Wetherspoon freehouse is unusual. Most outlets in the Wetherspoon estate have names based on an historical association. This one derives from a comment.

When looking at the plan of the block originally occupied by Lewis’s store, the Wetherspoon Chairman Tim Martin remarked that it looked like a square peg in a round hole.

This observation went on to become the pub name.

The expression ‘a square peg in a round hole’ is generally used to describe an unusual individual who does not fit comfortably into the niche society has prepared for them. It therefore fits in very well with the innovative outlook of J D Wetherspoon PLC.

Framed photographs and text about Tony Hancock.

The text reads: Tony Hancock was born in Southam Road, Hall Green, Birmingham, in 1924. His father, an entertainer and hotel manager, died in 1934 and Hancock and his brother were brought up by their mother and stepfather.

He left school aged fifteen and in 1942 joined the RAF. He failed an audition for the Entertainments National Service Assosiation (ENSA), and ended up on The Ralh Reader Gang Show. He stuck to entertainment after the War and became resident comedian at London’s Windmill Theatre, and worked on radio shows such as Workers’ Playtime and Variety Bandbox.

In 1951, he joined the cast of Educating Archie, his first step to national recognition. Three years later he was given his own BBC radio show, Hancock’s Half Hour. Hancock’s Half Hour, on radio and television, lasted for seven years, the peak period of Hancock’s career.

Personality problems, aided by alcohol, took their toll, and by 1967 he was on a downward spiral. He was contracted to make a series called Hancock Down Under for Australian television, but only completed three programmes.

On 24 June 1968, in Sydney, he was found dead in his apartment. In one of his suicide notes he wrote: “Things just seemed to go too wrong too many times”.

Top: Hancock with Peter Sellers (centre) and long-time co-star, Sid James

Above: A shot from Hancock’s doomed Australian series

Left: Nera the end – one of the last photos of Hancock.

Framed photos, illustrations and text about the world’s oldest lawn tennis club.

The text reads: Edgbaston Archery and Lawn Tennis Society is the oldest Lawn Tennis Club in the world, pre-dating the All-England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club by

just three weeks. The club was originally founded for archery in 1860, and croquet was added ten years later. Tennis seems to have made an appearance between 1873 and 1875.

The game, Thought to have been called “shairistrike”, was introduced by a Major Wingfield. But, the first game of “tennis” - or Perlota - had been played in 1865 by Major Harry Gen, clerk to the Birmingham Magistrates, and Mr J. Perera, a local merchant, in the garden of ‘Fairlawn’ in Ampton Road, Edgbaston.

The game of “Lawn Tennis” made a shaky start at the original Leamington Club, which subsequently closed. Tennis was taken up at Edgbaston soon after.

A fixture card for 1875 details matches to be played throughout the summer and states that prizes would be offered. Tennis was incorporated into the Society’s name in March 1877, three weeks before the All England Croquet Club added tennis to its title.

The first all-England Championships were held at Wimbledon in the same year.

Many of the terms used in the game originate from “Real” tennis, which has been played since the Middle Ages. The word ‘real’ is actually a corruption of Royal - Henry VIII was Real Tennis Champion of England. The game was played in court yards, including at Hampton Court Palace. Matches were “set” to last a fixed number of games and “service” derives from the fact that servants used to “serve” the ball. It was thought to be beneath the dignity of gentlemen to put the ball into play.

Above Right, playing tennis at the Society’s grounds around the turn of the Century.

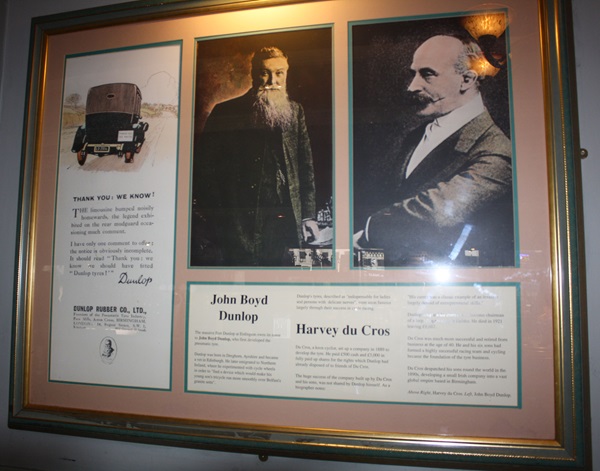

Framed photos and text about pneumatic tyre developers John Boyd Dunlop and Harvey du Cros.

The text reads: John Boyd Dunlop

The massive Fort Dunlop at Erdington owes its name to John Boyd Dunlop, who first developed the pneumatic tyre.

Dunlop was born in Dreghorn, Ayshire and became a vet in Edinburgh. He later emigrated to Northern Ireland, where he experimented with cycle wheels in order to “find a device which would make his young son’s tricycle run more smoothly over Belfast’s granite setts”.

Dunlop ‘s tyres, described as ‘indispensable for ladies and persons with delicate nerves”, were soon famous largely through their success in cycle racing.

Harvey du Cros

Du Cros, a keen cyclist, set up a company in 1889to develop the tyre. He paid £500 cash and £3,000 in fully paid up shares for the rights which Dunlop had already disposed of to friends of Du Cros.

The huge success of the company built up by Du Cros and his sons, was not shared by Dunlop himself. As a biographer notes: “His career was a classic example of an inventor largely devoid of entrepreneurial skills.”

Dunlop resigned the company to become chairman of a large drapers shop in Dublin. He died in 1921 leaving £9,687.

Du Cros was much more successful and retired from business at the age of 40. He and his six sons had formed a highly successful racing team and cycling became the foundation of the tyre business.

Du Cros despatched his sons round the world in the 1890s, developing a small Irish company into a vast global empire based in Birmingham.

Above Right, Harvey du Cros. Left, John Boyd Dunlop.

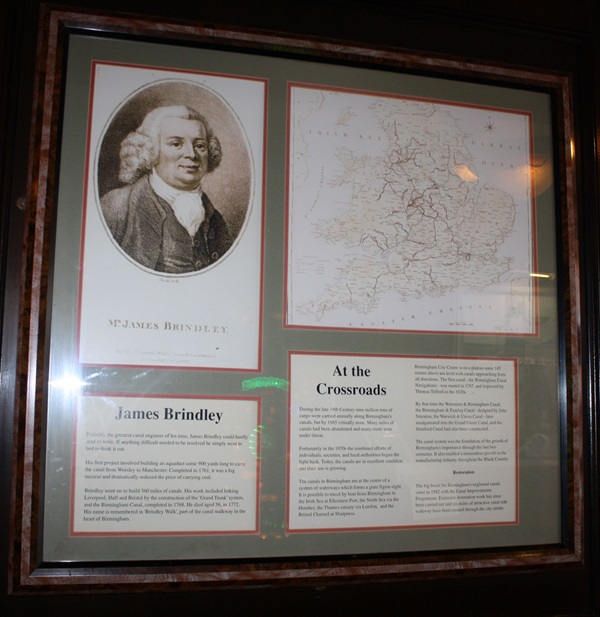

Framed illustrations and text telling the history of James Brindley and the development of the UK’s canal system.

The text reads: James Brindley

Probably the greatest canal engineer of his time, James Brindley could hardly read or write. If anything difficult needed to be resolved he simply went to bed to think it out.

His first project involved building and aqueduct some 900 yards long to carry the canal from Worsley to Manchester. Completed in 1761, it was a big success and dramatically reduced the price of carrying coal.

Brindley went on to build 360 miles of canals. His work included linking Liverpool, Hull and Bristol by the construction of the ‘Grand Trunk’ system, and the Birmingham Canal, completed in 1768. He died aged 56, in 1772. His name is remembered in ‘Brindley Walk’, part of the canal walkway in the heart of Birmingham.

At the Crossroads

During the late 19th Century nine million tons of cargo were carried annually along Birmingham’s canals, but by 1965 virtually none. Many miles of canals had been abandoned and many more were under threat.

Fortunately in the 1970s the combined efforts of individuals, societies, and local authorities began the fight back. Today, the canals are in excellent condition and their use is growing.

The canals of Birmingham are at the centre of a system of waterways which forms a giant figure of eight. It is possible to travel by boat from Birmingham to the Irish Sea at Ellesmere Port, the North Sea via the Humber, the Thames estuary via London, and the Bristol Channel at Sharpness.

Birmingham City Centre is on a plateau some 145 metres above sea level with canals approaching from all directions. The first canal – the Birmingham Canal Navigations – was started in 1767, and improved by Thomas Telford in the 1820s.

By that time the Worcester and Birmingham Canal; the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal – designed by John Smeaton; the Warwick & Union Canal – later amalgamated into the Grand Union Canal, and the Stratford canal had also been constructed.

The canal system was the foundation of the growth of Birmingham’s importance through the last two centuries. It also enabled a tremendous growth in the manufacturing industry throughout the Black Country.

The big boost for Birmingham’s neglected canals came in 1982 with the Canal Improvements Programme. Extensive restoration work has since been carried out and six miles off attractive canal side walkway have been created through the city centre.

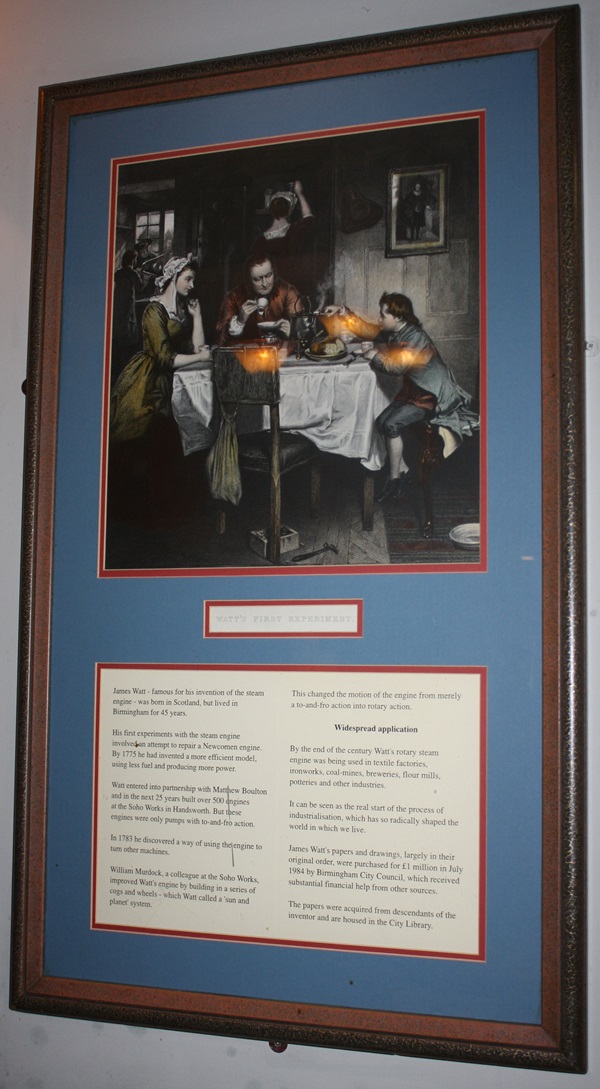

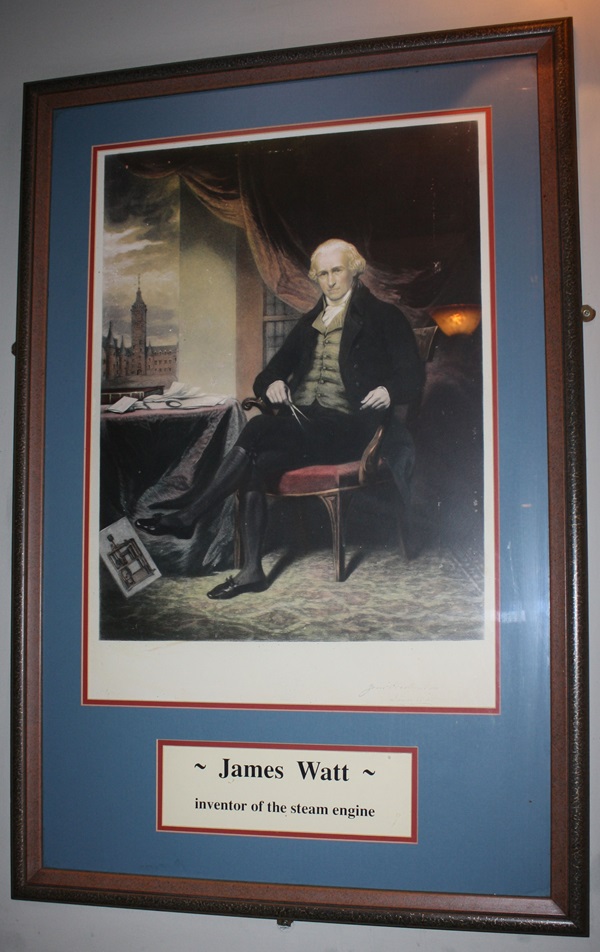

A framed print and text of James Watt, inventor of the steam engine.

The text reads: James Watt – famous for his invention of the steam engine – was born in Scotland, but lived in Birmingham for 45 years.

His first experiments with the steam engine involved an attempt to repair a Newcomen engine. By 1755 he had invented a more efficient model, using less fuel and producing more power.

Watt entered into partnership with Matthew Boulton and in the next 25 years built over 500 engines at the Soho Works in Handsworth. But these engines were only pumps with no to-and-fro action.

In 1783 he discovered a way of using the engine to turn other machines.

William Murdock, a colleague at the Soho Works, improved Watt’s engine by building in a series of cogs and wheels – which Watt called a ‘sun and planet’ system.

This changed the motion of the engine from merely a to-and-fro action into rotary action.

By the end of the century Watt’s rotary steam engine was being used in textiles factories, ironworks, coal-mines, breweries, flour mills, potteries and other industries.

It can be seen as the real start of the process of industrialisation, which has so radically shaped the world we live in today.

James Watt’s papers and drawings, largely in their original order, were purchased for £1 million in July 1984 by Birmingham City Council, which received substantial financial help from other sources.

The papers were acquired from descendants of the inventor and are housed in the City Library.

A framed print of James Watt, inventor of the steam engine.

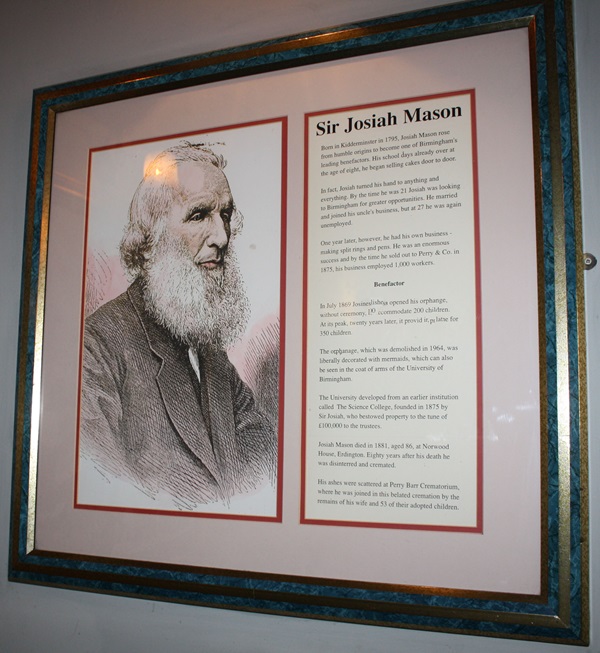

A framed illustration and text about Sir Josiah Mason, one of Birmingham’s leading benefactors.

The text reads: Born in Kidderminster in 1795, Josiah Mason rose from humble origins to become one of Birmingham’s leading benefactors. His school days already over at the age of eight, he began selling cakes door to door.

In fact, Josiah turned his hand to anything and everything. By the time he was 21 Josiah was looking to Birmingham for greater opportunities. He married and joined his uncle’s business, but at 27 he was again unemployed.

One year later, however, he had his own business – making split rings and pens. He was an enormous success and by the time he sold out to Perry & Co. in 1875, his business employed 1,000 workers.

In July 1869 Josiah mason opened his orphanage, without ceremony, to accommodate 200 children. At its peak, twenty years later, it provided refuge for 350 children.

The orphanage, which was demolished in 1964, was liberally decorated with mermaids, which can also be seen in the coat of arms of the University of Birmingham.

The university developed from an earlier institution called The Science College, founded in 1875 by Sir Josiah, who bestowed property to the tune of £100,000 to the trustees.

Josiah Mason died in 1881, aged 86, at Norwood House, Erdington. Eighty years after his death he was disinterred and cremated.

His ashes were scattered at Perry Barr Crematorium, where he was joined in this belated cremation by the remains of his wife and 53 of their adopted children.

Framed prints of a BSA Sunbeam motorcycle advert and a 1950s UK BSA Motorcycling Annual cover.

Framed copies of the front covers of Motor Cycling and The Motor Cycle magazines.

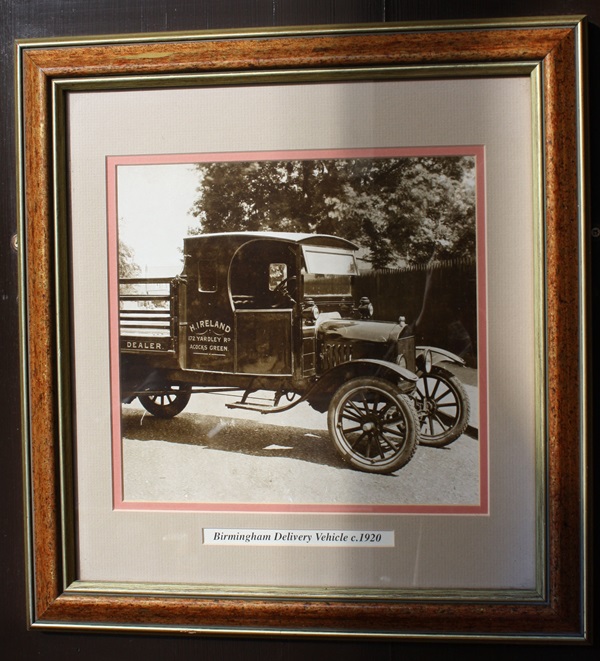

Framed photo of a Birmingham Delivery Vehicle c1920.

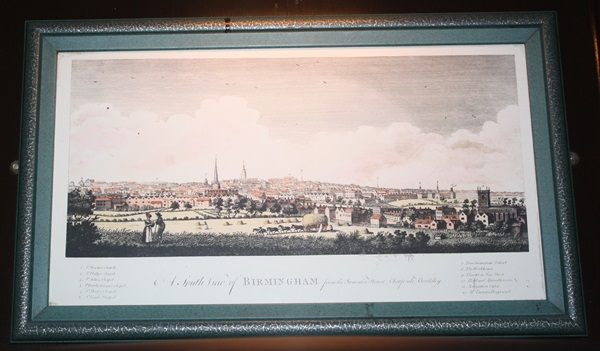

A framed illustration of a south view of Birmingham.

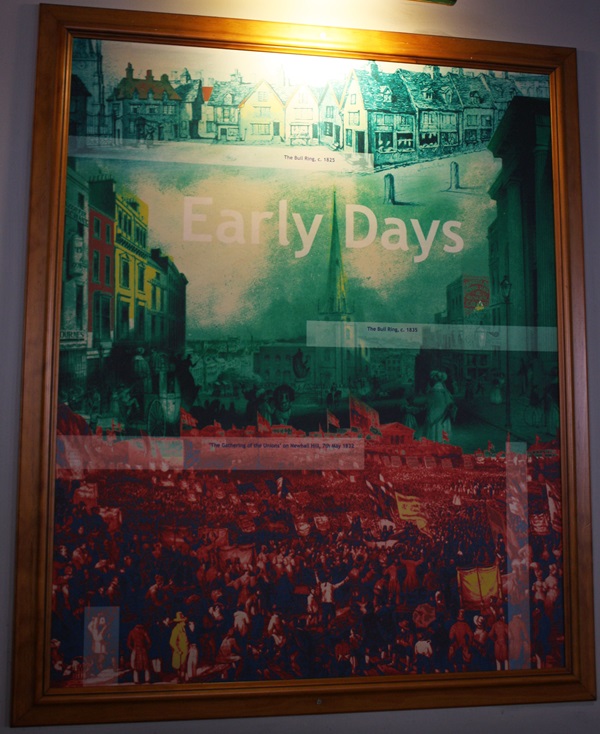

Framed prints entitled Early Days.

Illustrations include (top): The Bull Ring, c. 1835 and ‘The Gathering of the Unions’ on Newhall Hill, 7 May 1832.

Framed photographs and prints of cultural events in Birmingham, during 1869–1901.

A framed print and text about Corporation Street.

The text reads: Birmingham was transformed in the 1880’s. In the middle of the city a new shopping centre was carved out. Joseph Chamberlain had cajoled and bullied the Town Council into backing major improvements, centred on a new shopping street, “a great street, as broad as a Parisian boulevard”. This became Corporation Street, springing up where an ancient and squalid slum area had been cleared away.

They began to build Corporation Street in 1878. The building you are now in was opened on 22nd September, 1885. Corporation Street was not finally completed until 1903.

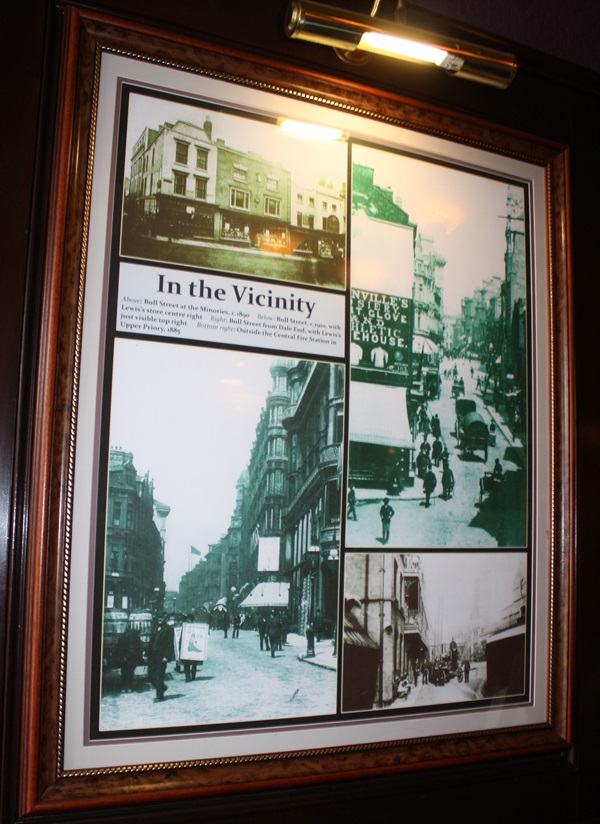

Framed photographs and text entitled In the Vicinity.

The photos include (top left) Bull Street at the Minories, c.1890; (bottom left) Bull Street, c.1910, with Lewis’s store centre right; (top right) Bull Street from Dale End, with Lewis’s just visible top right; (bottom right) Outside the Central Fire Station in Upper Priory, 1885.

Framed photographs entitled Corporation Street – before and after.

Photos include (clockwise from top left): The Old Farriers Arms, one of the many ‘slum area’ buildings behind High Street cleared away when work began to create Corporation Street; Corporation street with The Grand Theatre on the right, c.1900; Corporation Street, looking towards Lewis’s Department Store in the 1950s; Lichfield Street before it was demolished and became the lower end of Corporation Street.

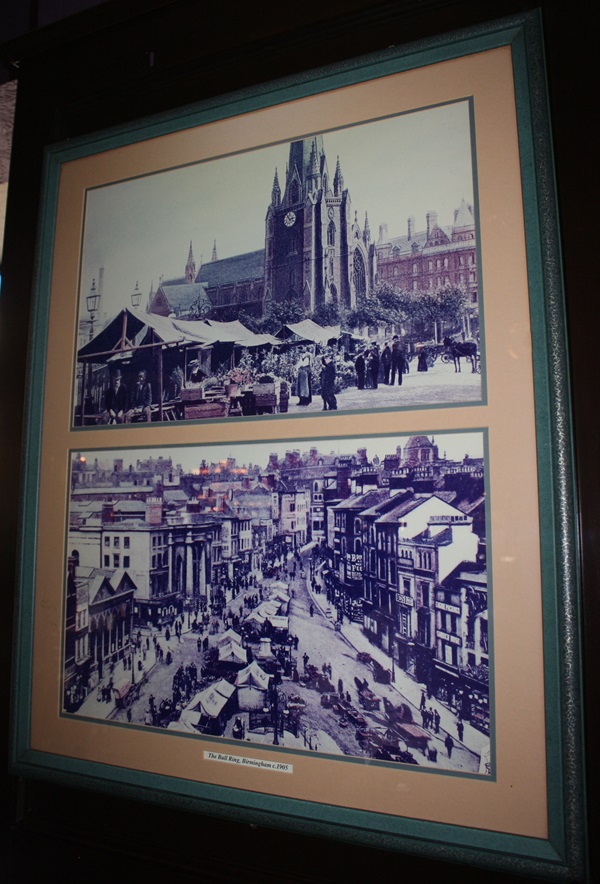

Framed photographs of The Bull Ring, Birmingham c1905.

Framed photograph of New Street, Birmingham c1904.

Framed photographs of Lewis’s Department Store.

Captions read (top): Lewis’s looms over Corporation Street in the 1920’s; Lewis’s, c.1960.

A framed photograph of Corporation Street, c1900.

Framed photographs of Corporation Street.

Above: The lower end of Corporation Street (then Litchfield Street) c.1870, before clearance

Below: The same area c.1895, looking towards the Law Courts and the Central Hall.

Framed photograph of Birmingham delivery vehicle c1930.

Framed photograph of The Market, Birmingham, c1935.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

A photograph of the entrance to Minories Shopping Arcade.

A photograph of the corner of the original Lewis’s Department Store, where Bull Street meets Corporation Street. The pub can be seen below.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk