This former long-standing garage is situated in the area once known as Barum Top, so named from the Yorkshire word ‘bouram’, meaning a natural watercourse. Before the advent of purpose-built drainage systems, this watercourse descended from Barum Top into Hebble Brook.

Prints and text about the textiles in Halifax.

The text reads: Halifax world-famous Piece Hall demonstrates the centre old importance of the local cloth trade. Officially known as the Halifax Merchant’s Hall, the Piece Hall opened in 1779, providing 315 rooms around a quadrangle for the display and sale of cloth “pieces”.

In time, the cottage weaver was replaced by mills, making the Piece Hall’s original purpose redundant. After serving as home to Halifax’s Wholesale Fruit and Vegetable Market, the Piece Hall was in danger of demolition during the 1960s, and being replaced by a car park!

The historic building was saved by just one vote at a meeting of Halifax Town Council. The Piece Hall was restored to its former glory and reopened in 1976.

In the early 19th century, the economic life of Halifax was dominated by the textile mills of James Akroyd & Sons.

As early as the 1840s, their factories employed over 2,000 people at Copley and Haley Hill.

The Akroyds were challenged by a rival dynasty, the Crossleys, whose Dean Clough carpet mills became the town’s largest employers in the late 1850s.

Weaver John Crossley became manager of Job Lee’s carpet works in 1800, taking over the business on Lee’s death. John’s sons introduced power-looms, and oversaw a huge expansion programme.

The company, which once claimed to be the world’s largest manufacturer of carpets, closed in 1982. Since its demise, the former carpet factory has been transformed to host many separate enterprises, including the Dean Clough Galleries displaying a wide range of contemporary art and design.

Above: The Piece Hall

Above right: The home of John and Martha Crossley, 1801, with Dean Clough Mill in the background

Right: Woolshops.

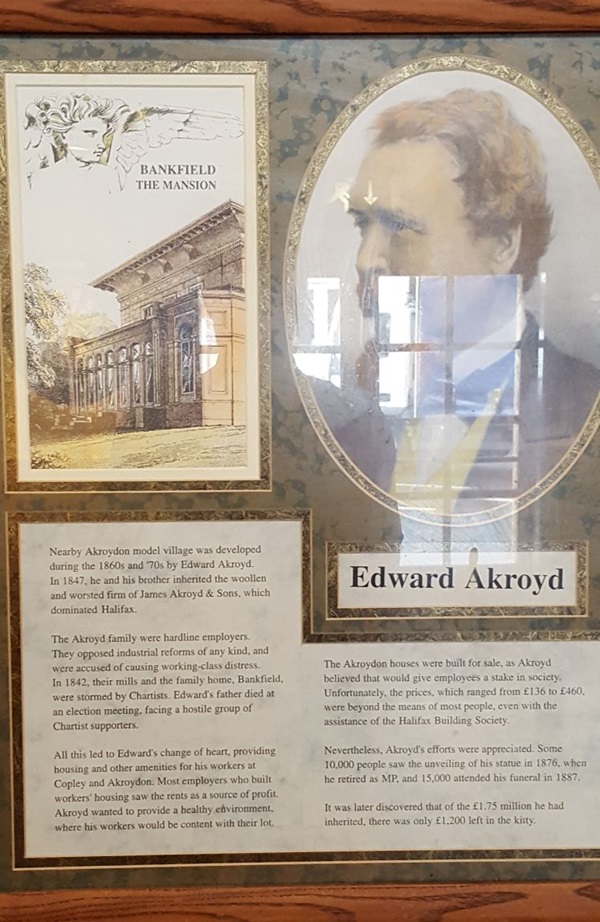

Prints and text about Edward Akroyd.

The text reads: Nearby Akroydon model village was developed during the 1860s and 70s by Edward Akroyd. In 1847, he and his brother inherited the woollen and worsted firm of James, Akroyd & Sons, which dominated Halifax.

The Akroyd family were hardline employers. They opposed industrial reforms of any kind, and were accused of causing working-class distress. In 1842, their mills and the family home, Bankfield, were stormed by Chartists. Edward’s father died at an election meeting, facing a hostile group of Chartist supporters.

All this led to Edward’s change of heart, providing housing and other amenities for his workers at Copley and Akroydon. Most employers who built workers’ housing saw the rents as a source of profit. Akroyd wanted to provide a healthy environment, where his workers would be content with their lot.

The Akroydon houses were built for sale, Akroyd believed that would give employees a stake in society. Unfortunately, the prices, which ranged from £136 to £460, were beyond the means of most people, even with the assistance of the Halifax Building Society.

Nevertheless, Akroyd’s efforts were appreciated. Some 10,000 people saw the unveiling of his statue in 1876, when he retired as MP, and 15,000 attended his funeral in 1887.

It was later discovered that of the £1.75 million he had inherited, there was only £1,200 left in the kitty.

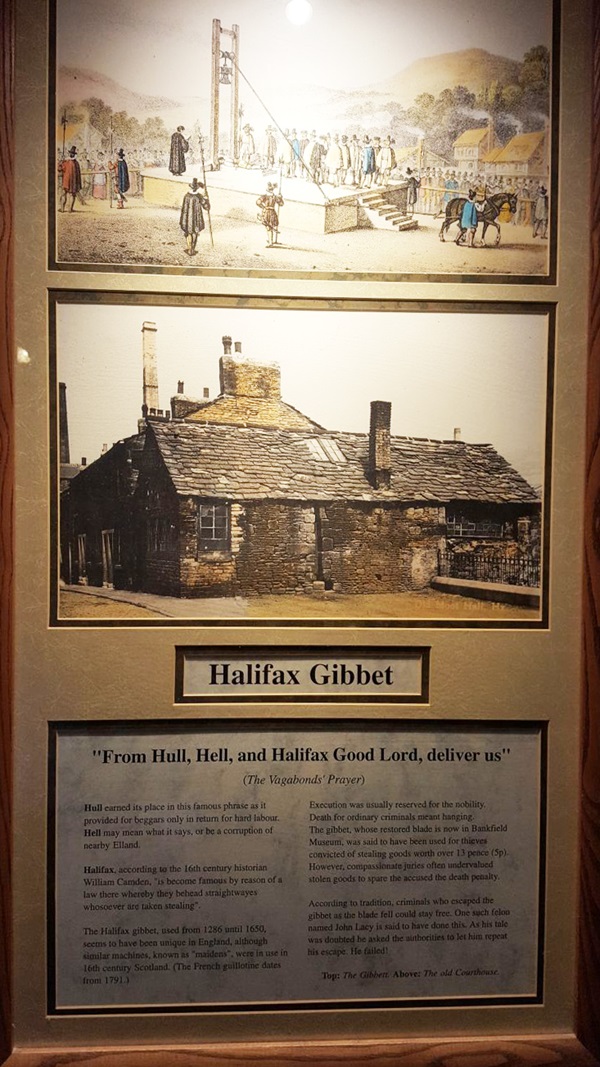

An illustration, photograph and text about the Halifax Gibbet.

The text reads: “From Hull, Hell, and Halifax Good Lord, deliver us” (The Vagabonds’ Prayer).

Hull earned its place in this famous phrase as it provided for beggars only in return for hard-labour. Hell may mean what it says, or be a corruption of nearby Elland.

Halifax, according to the 16th century historian William Camden, “is become famous by reason of a law there whereby they behead straightwayes whosever are taken stealing”.

The Halifax Gibbet, used from 1286 until 1650, seems to have been unique in England, although similar machines, known as “maidens”, were in use in 16th century Scotland. (The French guillotine dates from 1791).

Execution was usually reserved for the nobility. Death for ordinary criminals meant hanging. The gibbet, whose restored blade is now in Bankfield Musuem, was said to have been used for thieves convicted of stealing goods worth over 13 pence (5p). However, compassionate juries often undervalued stolen goods to spare the accused the death penalty.

According to tradition, criminals who escaped the gibbet as the blade fell could stay free. One such felon named John Lacy is said to have done this. As his tale was doubted he asked the authorities to let him repeat his escape. He failed!

Top: The Gibbet

Above: The old Courthouse.

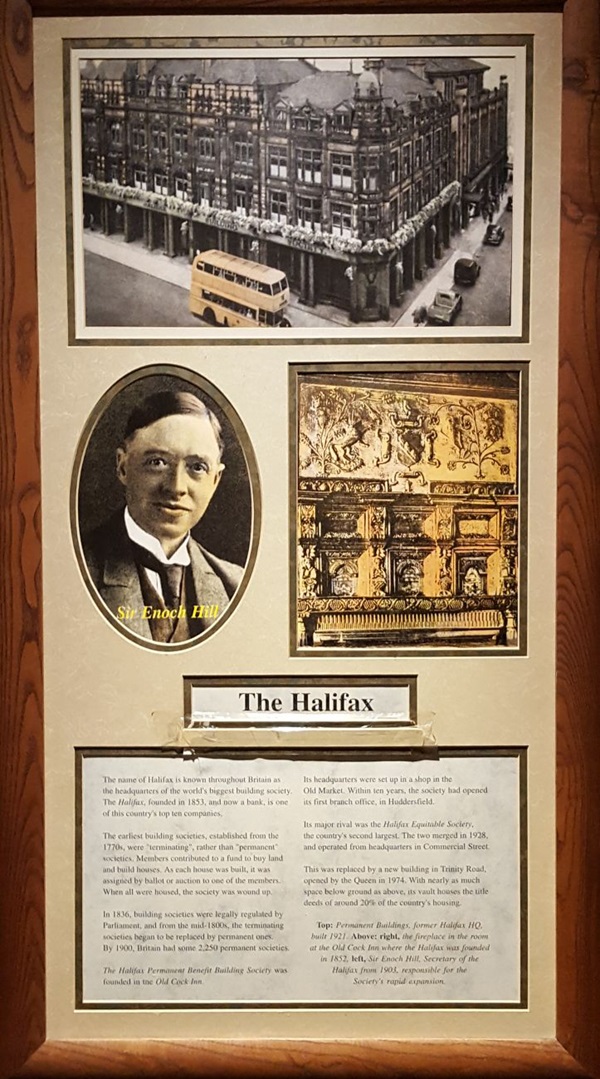

Photographs and text about Halifax.

The text reads: The name of Halifax is known throughout Britain as the headquarters of the world’s biggest building society. The Halifax, founded in 1853, and now a bank, is one of this country’s top ten companies.

The earliest building societies, established from the 1770s, were “terminating”, rather than “permanent” societies. Members contributed to a fund to buy land and build houses. As each house was built, it was assigned by ballot or auction to one of the members. When all were housed, the society was wound up.

In 1836, building societies were legally regulated by Parliament, and from the mid-1800s, the terminating societies, began to be replaced by permanent ones. By 1900, Britain had some 2,250 permanent societies.

The Halifax Permanent Benefit Building Society was founded in the Old Cock Inn.

Its headquarters were set up in a shop in the Old Market. Within ten years, the society had opened its first branch office, in Huddersfield.

Its major rival was the Halifax Equitable Society, the country’s second largest. The two merged in 1928, and operated from headquarters in Commercial Street.

This was replaced by a new building in Trinity Road, opened by the Queen in 1974. With nearly as much space below ground as above, its vault houses the title deeds of around 20% of the country’s housing.

Top: Permanent Buildings, former Halifax HQ, built in 1921

Above: right, the fireplace in the room at the Old Cock Inn where the Halifax was founded in 1852, left, Sir Enach Hill, Secretary of the Halifax from 1903, responsible for the Society’s rapid expansion.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk