Located just off Market Place, this is an 18th-century building, with a 19th-century shop front and some later additions. For 70 years or so, until c2000, this grade II listed building housed The London Draper’s Warehouse. Before the 1930s, several more drapers worked here, over a 60-year period. Earlier still, John James Fox & Son traded from these premises. They were also silk mercers and are recorded in St John’s Street, in 1839.

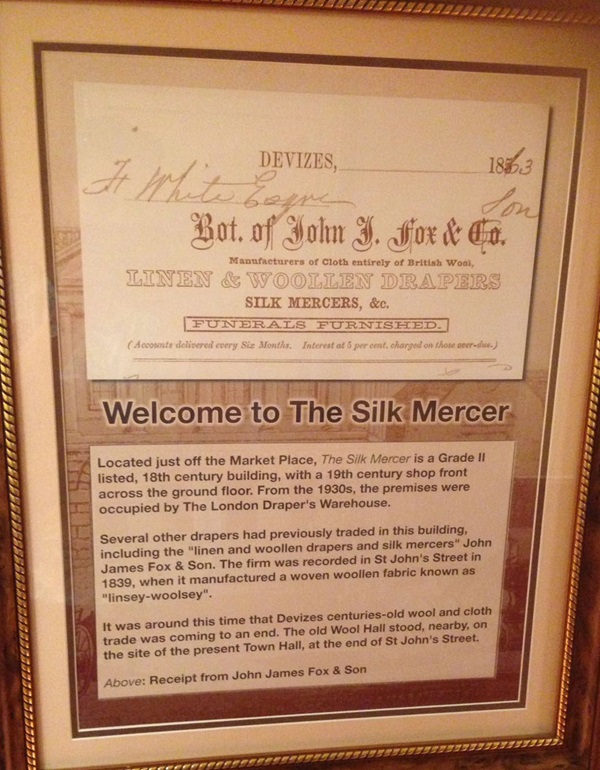

Text about The Silk Mercer.

The text reads: Located just off the Market Place, The Silk Mercer is a grade II listed, 18th century building, with a 19th century shop front across the ground floor. From the 1930s, the premises were occupied by The London Draper’s Warehouse.

Several other drapers had previously traded in this building, including the linen and woollen drapers and silk mercers John James Fox & Son. The firm was recorded in St John’s Street in 1839, when it manufactured a woven woollen fabric known as ‘linsey-woolsey’.

It was around this time that Devizes centuries-old wool and cloth trade was coming to an end. The old Wool Hall stood, nearby, on the site of the present Town Hall, at the end of St John’s Street.

Above: Receipt from John James Fox & Son.

Illustrations and text about Sir Thomas Lawrence.

The text reads: Two columns once stood near the Market Cross, surmounted by the black bear that is now over the porch of The Bear Hotel. The inn was the home of the young Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose father, also Thomas, became its landlord in 1773. Thomas junior, the youngest of three surviving children was an infant prodigy, who sketched the likenesses of the guests. He went on to become the leading portrait painter of his day and, in 1820, president of the Royal Academy. Fanny Burney, when she stayed at the hotel, thought Mrs Lawrence, the artist’s mother “…something above her station in her Inn”. She also mentions the two daughters who played piano and sang “but” she goes on “…the wonder of the family…was their brother, a most lovely boy of ten years of age…the wonder…of the times for his astonishing skill in drawing”.

Mrs Lawrence left in 1781, after Thomas senior had already departed for Weymouth and then London, having found the hotel trade unprofitable.

Top right: Thomas Lawrence senior

Above: Sir Thomas Lawrence as a boy

Right: The Bear Hotel, c1850, the earliest extant photograph of Devizes

Left: Portrait of the successful artist in his prime.

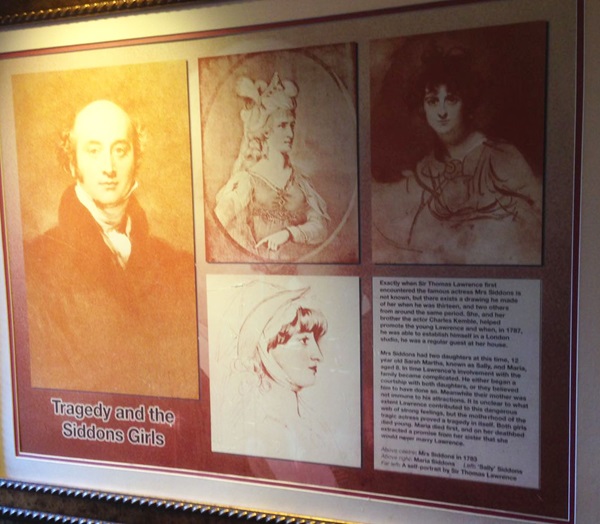

Illustrations, prints and text about the Siddons.

The text reads: Exactly when Sir Thomas Lawrence first encountered the famous actress Mrs Siddons is not known, but there exists a drawing he made of her when he was thirteen, and two others from around the same period. She, and her brother the actor Charles Kemble, helped promote the young Lawrence and when, in 1787, he was able to establish himself in a London studio, he was a regular guest at her house.

Mrs Siddons had two daughters at this time, 12 year old Sarah Martha, known as Sally, and Maria, aged 8. In time Lawrence’s involvement with the family became complicated. He either began a courtship with both daughters, or they believed him to have done so. Meanwhile their mother was not immune to his attractions. It is unclear to what extent Lawrence contributed to this dangerous web of strong feelings, but the motherhood of the tragic actress provided a tragedy in itself. Both girls died young, Maria died first, and on her deathbed extracted a promise from her sister that she would never marry Lawrence.

Above centre: Mrs Siddons in 1783

Above right: Maria Siddons

Left: ‘Sally’ Siddons

Far left: A self-portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

An illustration of the great actress, and Lawrence’s friend and patron, Mrs Siddons, drawn by Lawrence in 1797.

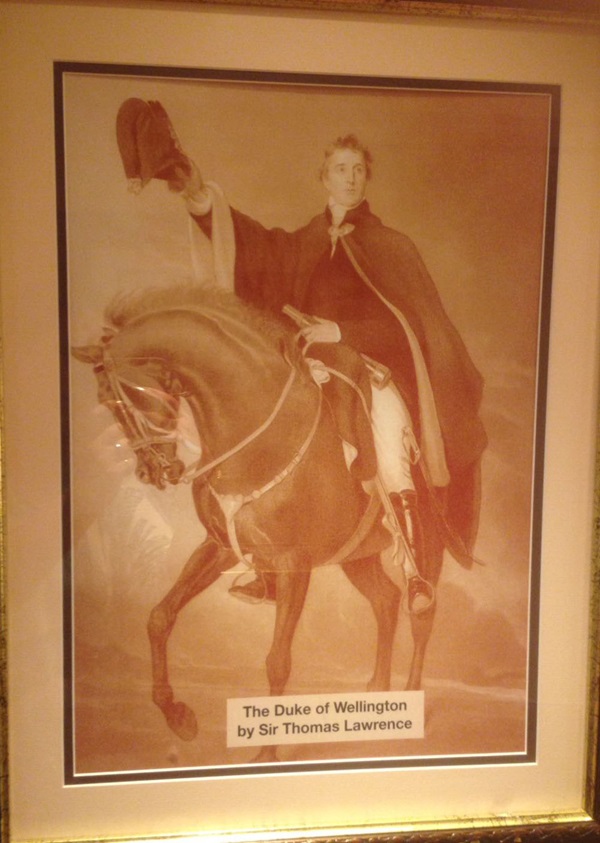

A print of the Duke of Wellington, by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

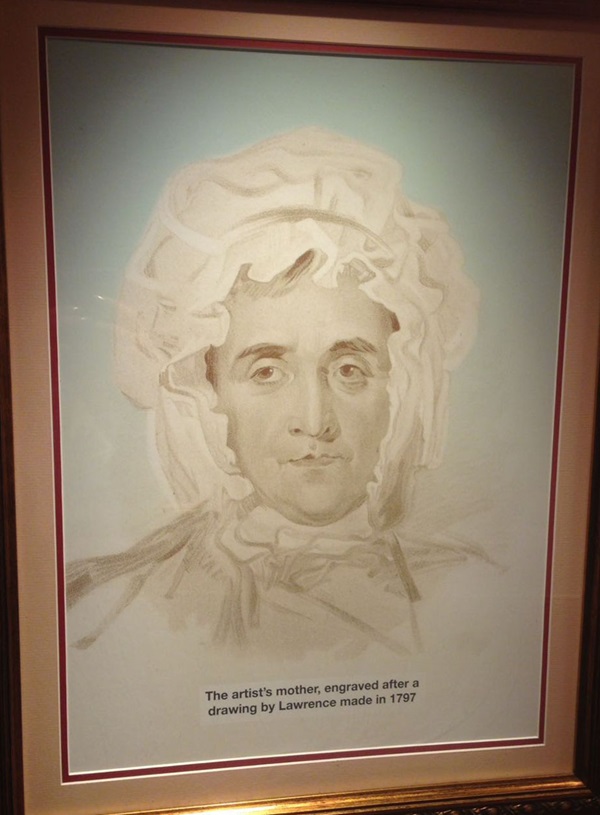

The artist’s mother, engraved after a drawing by Lawrence made in 1797.

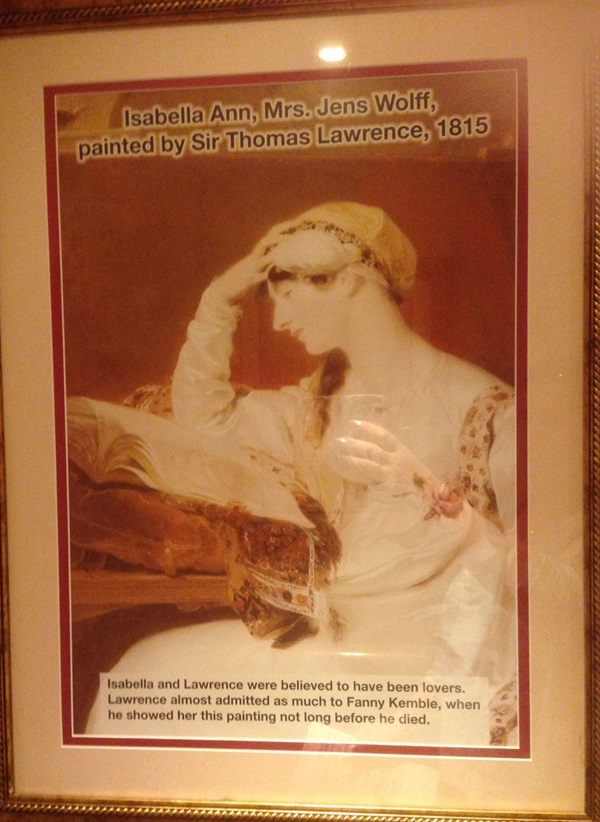

A print of Isabella Ann, Mrs Jens Wolff, painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1815.

Isabella and Lawrence were believed to have been lovers. Lawrence almost admitted as much to Fanny Kemble, when he showed her this painting not long before he died.

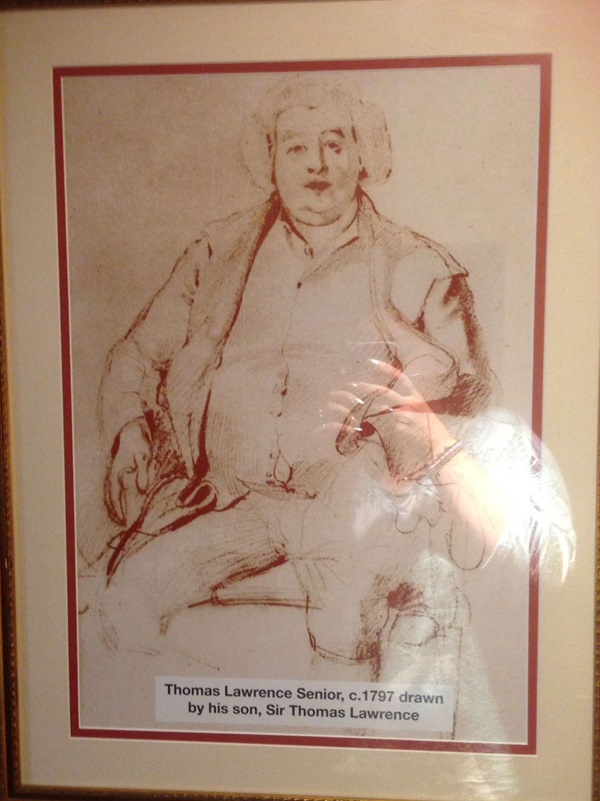

An illustration of Thomas Lawrence Senior, c1797, drawn by his son, Sir Thomas Lawrence.

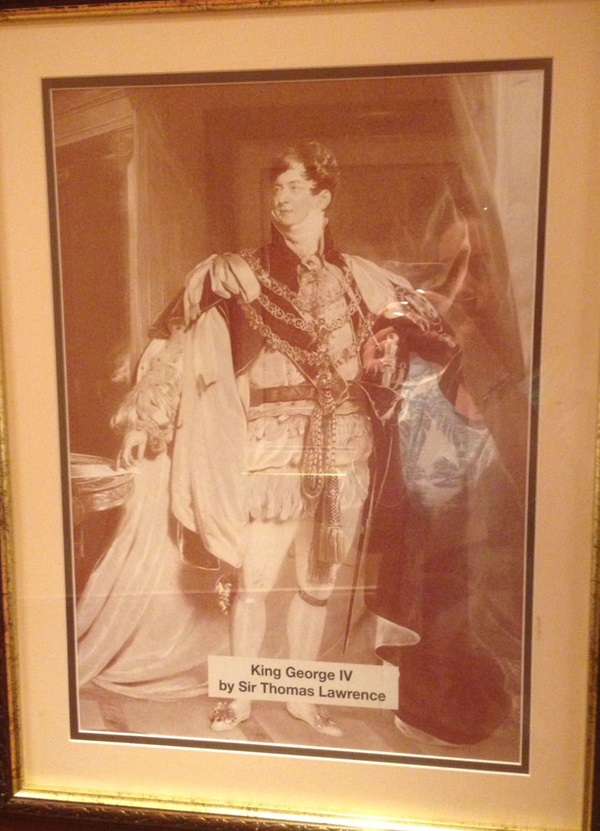

An illustration of King George IV, by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Prints and text about the Kennet and Avon Canal.

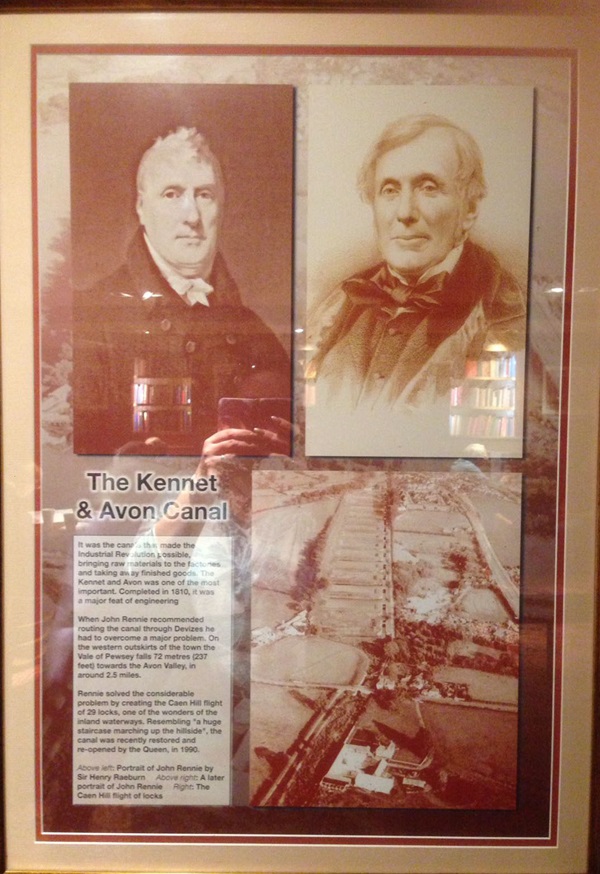

The text reads: It was the canals that made the Industrial Revolution possible, bringing raw materials to the factories and taking away finished goods. The Kennet and Avon was one of the most important. Completed in 1810, it was a major feat of engineering.

When John Rennie recommended routing the canal through Devizes he had to overcome a major problem. On the western outskirts of the town the Vale of Pewsey falls 72 metres (237 feet) towards the Avon Valley, in around 2.5 miles.

Rennie solved the considerable problem, by creating the Caen Hill flight of 29 Locks, one of the wonders of the inland waterways. Resembling “a huge staircase marching up the hillside”, the canal was recently restored and re-opened by the Queen, in 1990.

Above left: Portrait of John Rennie by Sir Henry Raeburn

Above right: A later portrait of John Rennie

Right: The Caen Hill flight of locks.

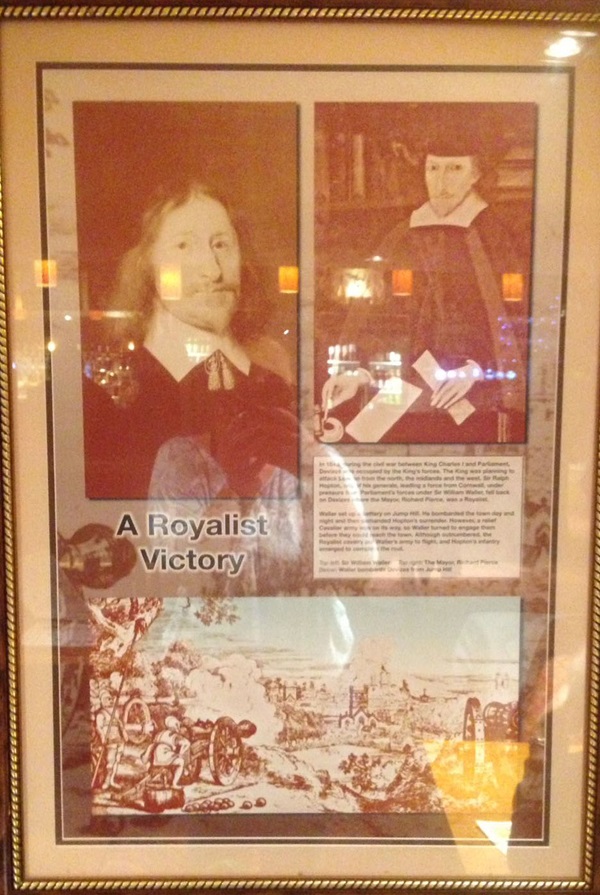

Prints and text about the Civil War.

The text reads: In 1643, during the civil war between King Charles I and Parliament, Devizes was occupied by the King’s forces. The King was planning to attack London from the north, the midlands and the west. Sir Ralph Hopton, one of his generals, leading a force from Cornwall, under pressure from Parliament’s forces under Sir William Waller, fell back on Devizes where the mayor, Richard Pierce, was a Royalist.

Waller set up a battery on Jump Hill. He bombarded the town day and night and then demanded Hopton’s surrender. However, a relief Cavalier army was on its way, so Waller turned to engage them before they could reach the town. Although outnumbered, the Royalist cavalry put Waller’s army to flight, and Hopton’s infantry emerged to complete the rout.

Top left: Sir William Waller

Top Right: The mayor, Richard Pierce

Below: Waller bombards Devizes from Jump Hill.

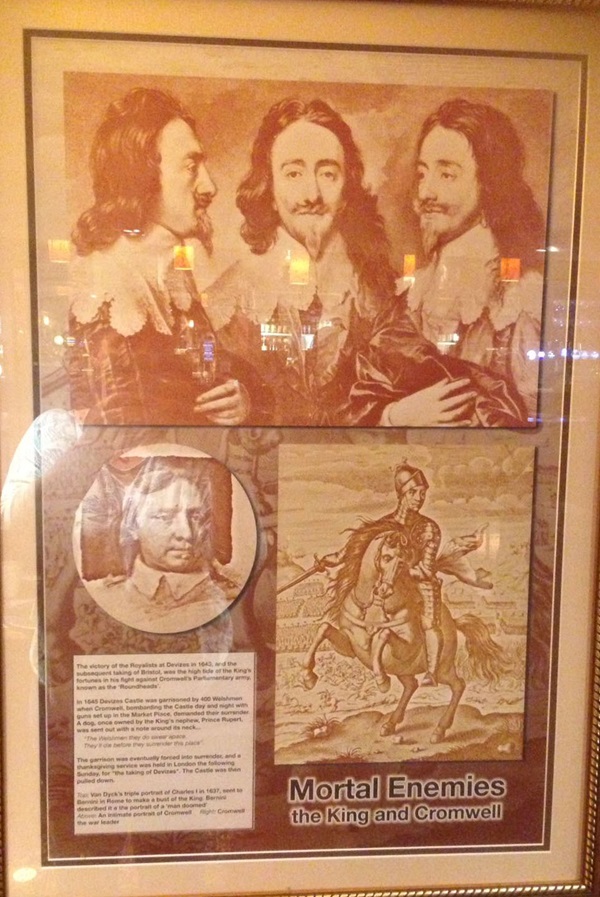

Illustrations and text about the King and Cromwell.

The text reads: The victory of the Royalists at Devizes in 1643, and the subsequent taking of Bristol, was the high tide of the King’s fortunes in his fight against Cromwell’s Parliamentary army, known as the ‘Roundheads’.

In 1645 Devizes Castle was garrisoned by 400 Welshmen when Cromwell, bombarding the castle day and night with guns set up in the Market Place, demanded their surrender. A dog, once owned by the King’s nephew, Prince Rupert, was sent out with a note around its neck…

“The Welshmen they do swear apace, They’ll die before they surrender this place”.

The garrison was eventually forced into surrender, and a thanksgiving service was held in London the following Sunday, for “the taking of Devizes”. The castle was then pulled down.

Top: Van Dyck’s triple portrait of Charles I in 1637, sent to Bernini in Rome to make a bust of the King. Bernini described it as the portrait of a ‘man doomed’

Above: An intimate portrait of Cromwell

Right: Cromwell the war leader.

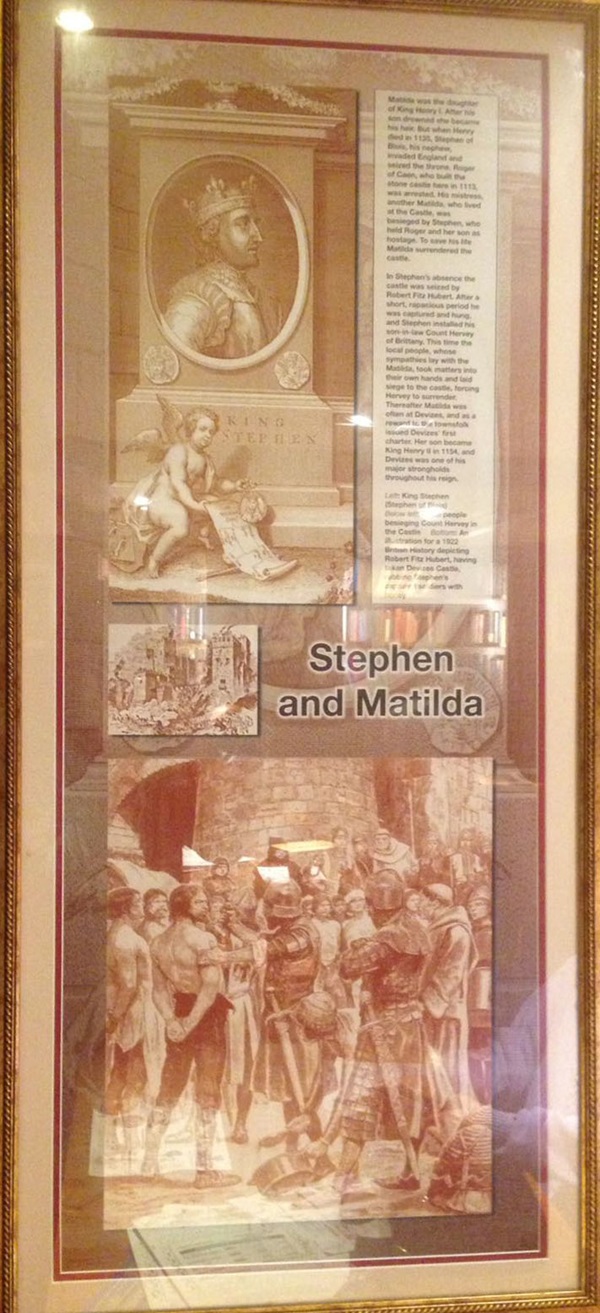

Illustrations and text about Stephen and Matilda.

The text reads: Matilda was the daughter of King Henry I. After his son drowned she became his heir. But when Henry died in 1135, Stephen of Blois, his nephew, invaded England and seized the throne. Roger of Caen, who built the stone castle here in 1113, was arrested. His mistress, another Matilda, who lived at the castle, was besieged by Stephen, who held Roger and her son as hostage. To save his life, Matilda surrendered the castle.

In Stephen’s absence the castle was seized by Robert Fitz Hubert. After a short, rapacious period he was captured and hung, and Stephen installed his son-in-law Count Hervey of Brittany. This time the local people, whose sympathies lay with Matilda, took matters into their own hands and laid siege to the castle, forcing Hervey to surrender. Thereafter Matilda was often at Devizes, and as a reward to the townsfolk issued Devizes’ first charter. Her son became King Henry II in 1154, and Devizes was one of his major strongholds throughout his reign.

Left: King Stephen (Stephen of Blois)

Below Left: Local people besieging Count Hervey in the castle

Bottom: An illustration for a 1922 British history depicting Robert Fitz Hubert, having taken Devizes Castle, rubbing Stephens captured soldiers with honey.

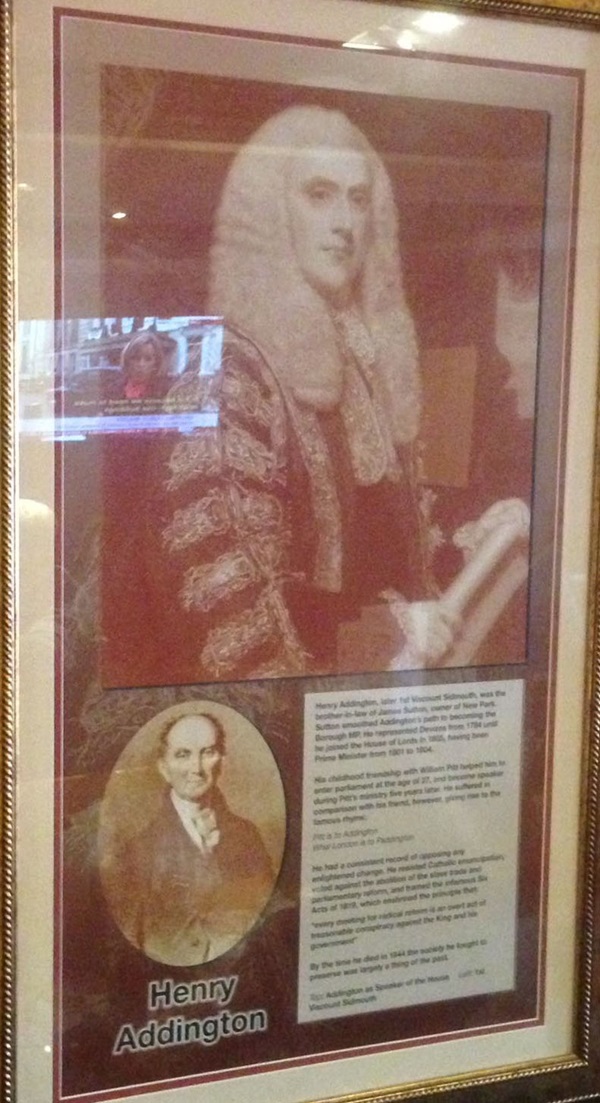

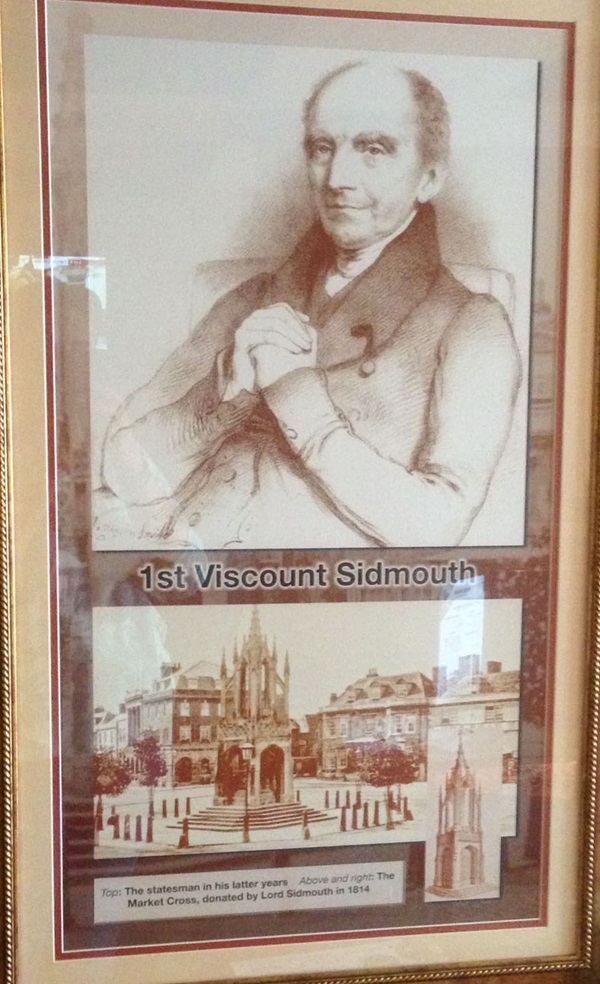

Prints and text about Henry Addington.

The text reads: Henry Addington, later 1st Viscount Sidmouth, was the brother-in-law of James Sutton, owner of New Park. Sutton smoothed Addington’s path to becoming the borough MP. He represented Devizes from 1784 until he joined the House of Lords in 1805, having been Prime Minister from 1801 to 1804.

His childhood friendship with William Pitt helped him to enter parliament at the age of 27, and become speaker during Pitt’s ministry five years later. He suffered in comparison with his friend, however, giving rise to the famous rhyme:

Pitt is to Addington

What London is to Paddington

He had a consistent record of opposing any enlightened change. He resisted Catholic emancipation, voted against the abolition of the slave trade and parliamentary reform, and framed the infamous Six Acts of 1819, which enshrined the principle that:

“Every meeting for radical reform is an overt act of treasonable conspiracy against the king and his government”.

By the time he died in 1844 the society he fought to preserve was largely a thing of the past.

Top: Addington as Speaker of the House

Left: 1st Viscount Sidmouth.

An illustration of the 1st Viscount Sidmouth and the Market Cross he donated in 1814.

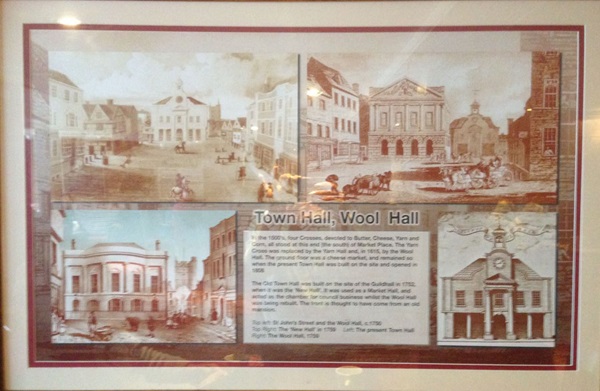

Illustrations and text about Town Hall and Wool Hall.

The text reads: In the 1500s, four crosses, devoted to butter, cheese, yarn and corn, all stood at this end (the south) of Market Place. The Yarn Cross was replaced by the Yarn Hall and, in 1615, by the Wool Hall. The ground floor was a cheese market, and remained so when the present Town Hall was built on the site and opened in 1808.

The Old Town Hall was built on the site of the Guildhall in 1752, when it was the New Hall. It was used as a Market Hall, and acted as the chamber for council business whilst the Wool Hall was being rebuilt. The front is thought to have come from an old mansion.

Top left: St John’s Street and the Wool Hall, c1750

Top Right: The New Hall in 1759

Left: The present Town Hall

Right: The Wool Hall, 1759.

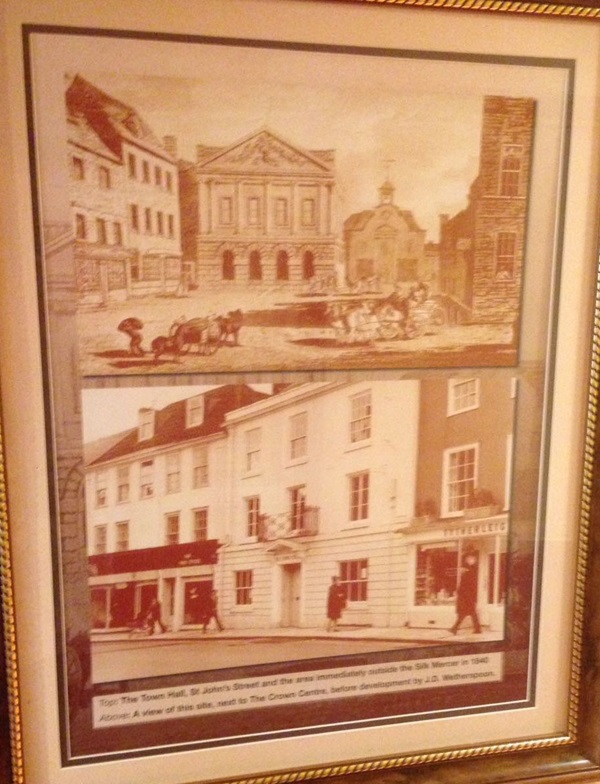

An illustration and photograph of the Town Hall.

Top: The Town Hall, St John’s Street and the area immediately outside The Silk Mercer in 1840

Above: A view of this site, next to The Crown Centre, before development by J D Wetherspoon.

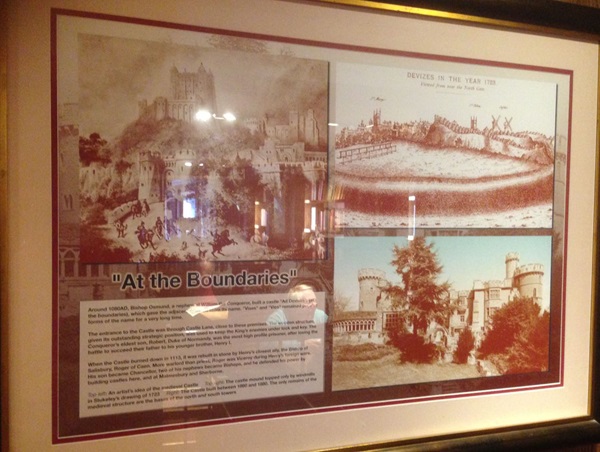

Illustrations, a photograph and text about the castle named Ad Devisas.

The text reads: Around 1080AD, Bishop Osmund, a nephew of William the Conqueror, built a castle Ad Devisas, (at the boundaries), which gave the adjacent planned town its name. ‘Vises’ and ‘Vies’ remained popular forms of the name for a very long time.

The entrance to the castle was through Castle Lane, close to these premises. The wooden structure, given its outstanding strategic position, was used to keep the King’s enemies under lock and key. The Conqueror’s eldest son, Robert, Duke of Normandy, was the most high profile prisoner, after losing the battle to succeed their father to his younger brother, Henry I.

When the castle burned down in 1113, it was rebuilt in stone by Henry’s closest ally, the Bishop of Salisbury, Roger of Caen. More warlord than priest, Roger was viceroy during Henrys foreign wars. His son became chancellor, two of his nephews became bishops, and he defended his power by building castles here, and at Malmesbury and Sherborne.

Top left: An artist’s idea of the medieval castle

Top right: The castle mound topped only by windmills in Stukeley’s drawing of 1723

Right: The castle built between 1860 and 1880. The only remains of the medieval structure are the bases of the north and south towers.

An illustration, photographs and text about the Parish of St John’s.

The text reads: The church of St John the Baptist is thought to have been built for the castle garrison around 1150. Hubert de Burgh, sent to the castle in 1232 as a prisoner, was carried, still in fetters, to St John’s Church to claim sanctuary in 1233. The castle governor violated the church’s privilege by having Hubert dragged out and taken back to the castle. The entire garrison was excommunicated as a result, and Henry III was forced to have Hubert returned to St John’s from where he was liberated by the King’s baronial opponents and carried off to Wales.

Until the early 19th century, the Borough of Devizes was made up of the parishes of St John and St Mary, the first comprised what had been the castle precincts, and was known as the New Port, first recorded in 1309. St John’s Street adopted its name, in 1737-8, and leads to St John’s Church and into Long Street. The two thoroughfares were the main area of building activity in 18th century Devizes, and the most fashionable part of town.

Top left: Hubert de Burgh rescued from St John’s Church

Top right: St John’s Church

Right: Long Street.

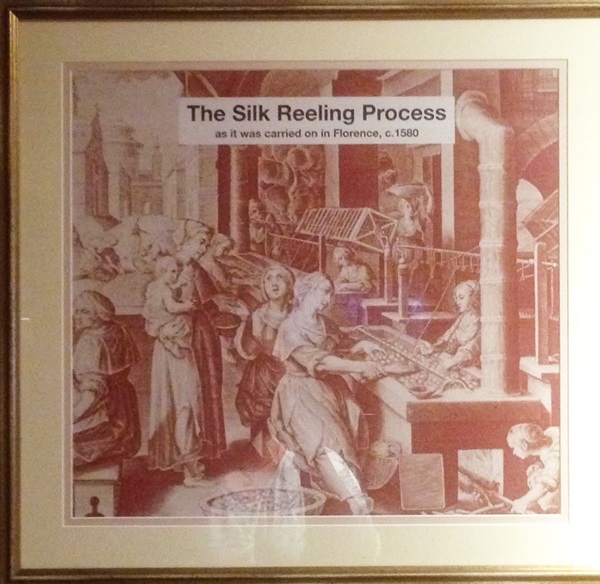

An illustration of the silk reeling process, as it was carried on in Florence, c1580.

An illustration of the silk reeling process, as it was carried on in Florence, c1580.

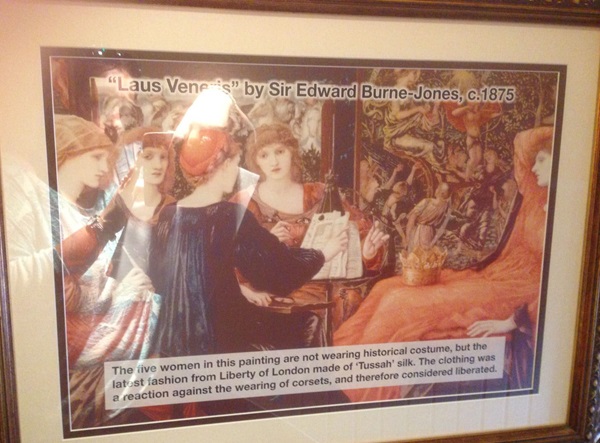

The five women in this painting are not wearing historical costume but the latest fashion from Liberty of London made of ‘Tussah’ silk. The clothing was a reaction against the wearing of corsets, and therefore considered liberated.

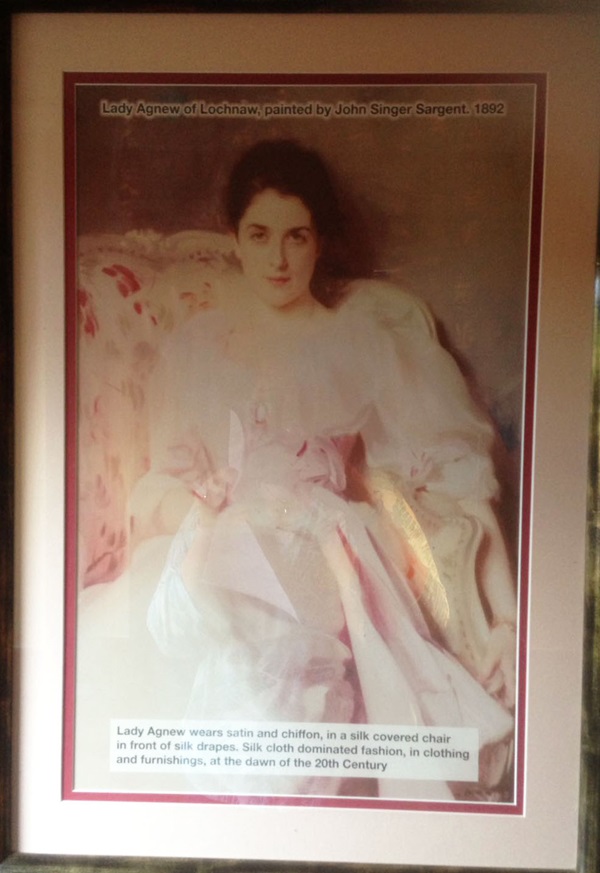

A copy of a painting of Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, by John Singer Sargent, 1892.

Lady Agnew wears satin and chiffon, in a silk covered chair in front of silk drapes. Silk cloth dominated fashion, in clothing and furnishings, at the dawn of the 20th century.

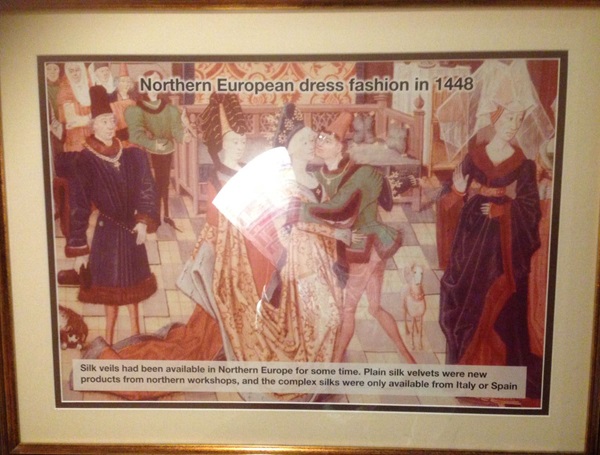

An illustration of Northern European dress fashion in 1448.

Silk veils had been available from Northern Europe for some time. Plain silk velvets were new products from northern workshops, and the complex silks were only available from Italy or Spain.

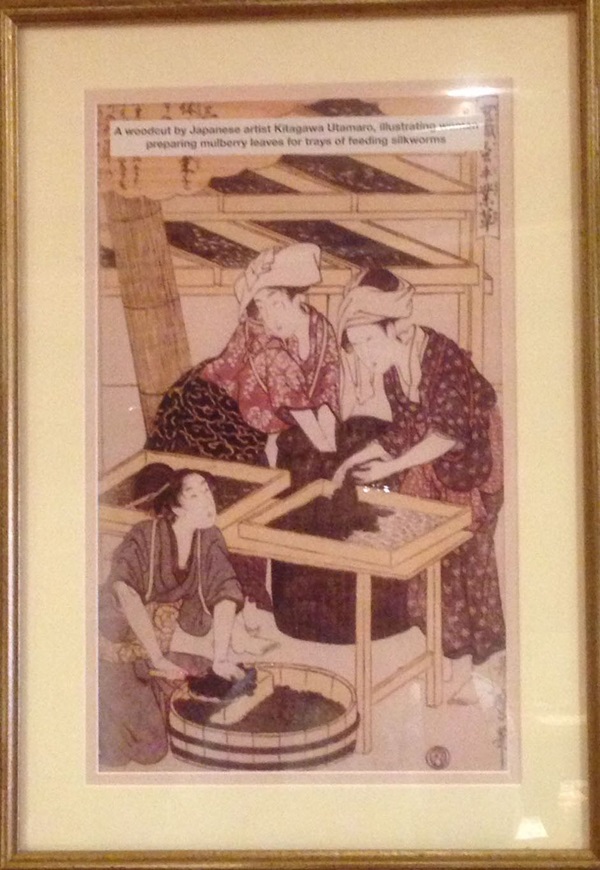

An illustration of a woodcut by Japanese artist Kitagawa Utamaro, illustrating women preparing mulberry leaves for trays of feeding silkworms.

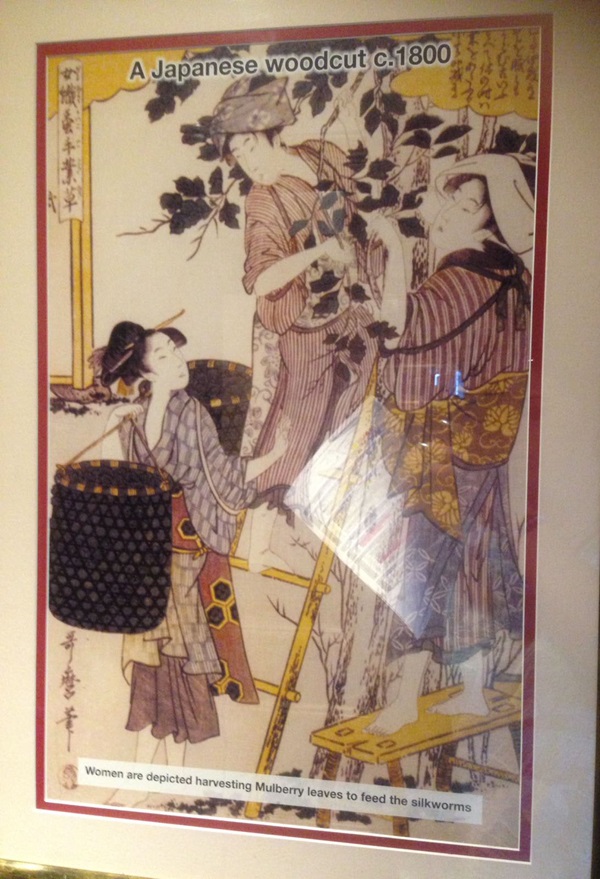

An illustration of a Japanese woodcut, c1800.

Women are depicted harvesting mulberry leaves to feed the silkworms.

External photographs of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk