This pub is the former Golden Cross Hotel, rebuilt in 1932 on the site of one of Bromsgrove’s oldest coaching inns of the same name.

An illustration and text about the Lickey Incline.

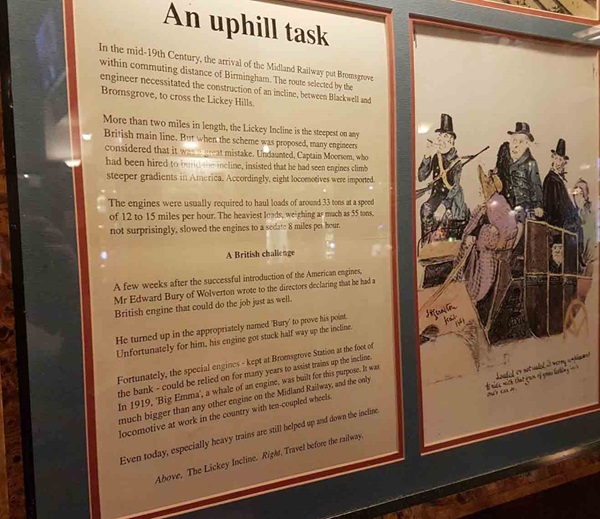

The text reads: In the mid 19th century, the arrival of the Midland Railway put Bromsgrove within commuting distance of Birmingham. The route selected by the engineer necessitated the construction of an incline, between Blackwell and Bromsgrove, to cross the Lickey Hills.

More than two miles in length, the Lickey Incline is the steepest on any British main line. But when the scheme was proposed, many engineers considered that is was a great mistake. Undaunted, Captain Moorsom, who had been hired to build the incline, insisted that he had seen engines climb steeper gradients in America. Accordingly, eight locomotives were imported.

The engines were usually required to haul loads of around 33 tons at a speed of 12 to 15 miles per hour. The heaviest loads, weighing as much as 55 tons, not surprisingly, slowed the engines to a sedate 8 miles per hour.

A few weeks after the successful introduction of the American engines, Mr Edward Bury of Wolverton wrote to the directors declaring that he had a British engine that could do the job just as well.

He turned up in the appropriately named ‘Bury’ to prove his point. Unfortunately for him, his engine got stuck half way up the incline.

Fortunately, the special engines – kept at Bromsgrove Station at the foot of the bank – could be relied on for many years to assist trains up the incline. In 1919, ‘Big Emma’, a whale of an engine, was built for this purpose. It was much bigger than any other engine on the Midland Railway, and the only locomotive at work in the country with ten-coupled wheels.

Even today, especially heavy trains are still helped up and down the incline.

Above, The Lickey Incline

Right, Travel before the railway.

Prints and text about Sir Edward Elgar.

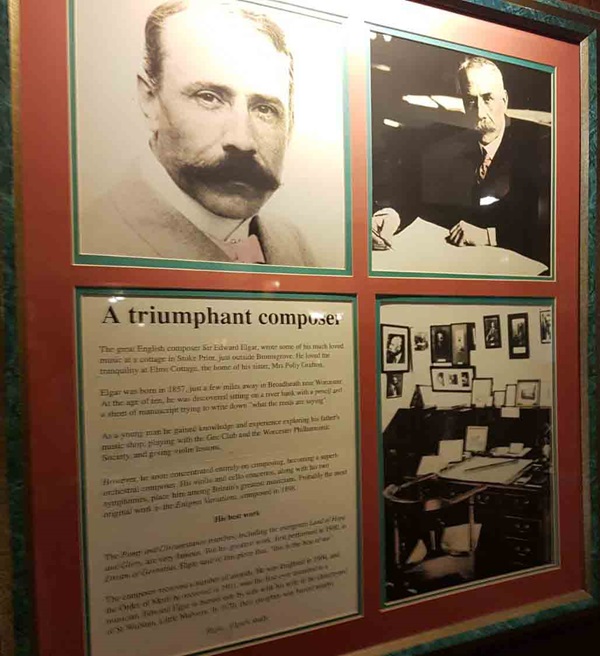

The text reads: The great English composer Sir Edward Elgar wrote some of his much loved music at a cottage in Stoke Prior, just outside Bromsgrove. He loved the tranquillity at Elms Cottage, the home of his sister, Mrs Polly Grafton.

Elgar was born in 1857, just a few miles away in Broadheath near Worcester. At the age of ten, he discovered sitting on a river bank with a pencil and a sheet of manuscript trying to write down “what the reeds are saying”.

As a young man he gained knowledge and experience exploring his father’s music shop; playing with the Gee Club and the Worcester Philharmonic Society, and giving violin lessons.

However, he soon concentrated entirely on composing, becoming a superb orchestral composer. His violin and cello concertos, along with his two symphonies, place him among Britain’s greatest musicians. Probably the most original work is the Enigma Variations, composed in 1898.

The Pomp and Circumstance marches, including the evergreen Land of Hope and Glory, are very famous. But his greatest work, first performed in 1900, is Dream of Gerontius. Elgar said of this piece that, “this is the best of me”.

The composer received a number of awards. He was knighted in 1904, and the Order of Merit he received in 1991, was the first ever awarded to a musician. Edward Elgar is buried side by side with his wife in the churchyard of St Wulstan, Little Malvern. In 1970, their daughter was buried nearby.

Right: Elgar’s study.

Illustrations and text about the Pilgrimage of Grace.

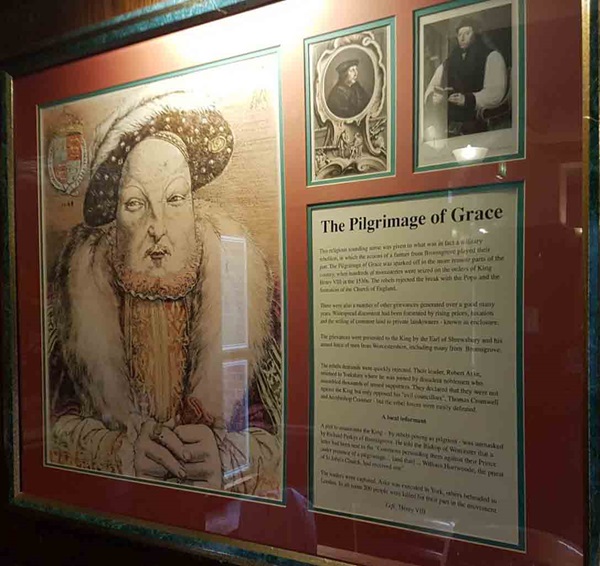

The text reads: This religious sounding name was given to what was in fact a military rebellion, in which the actions of a farmer from Bromsgrove played their part. The Pilgrimage of Grace was sparked off in the more remote parts of the country, when hundreds of monasteries were seized on the orders of King Henry VIII in the 1530s. The rebels rejected the break with the Pope and the formation of the Church of England.

There were also a number of other grievances generated over a good many years. Widespread discontent had been formed by rising prices, taxation and the selling of common land to private landowners – known as enclosure.

The grievances were presented to the King by the Earl of Shrewsbury and his armed force of men from Worcestershire, including many from Bromsgrove.

The rebel’s demands were quickly rejected. Their leader, Robert Alice, returned to Yorkshire where he was joined with dissident noblemen who assembled thousands of armed supporters. They declared that they were not against the King but only opposed his “evil councillors”. Thomas Cromwell and Archbishop Crammer – but the rebel forces were easily defeated.

A plot to assassinate the King – by rebels posing as pilgrims – was unmasked by Richard Perkys of Bromsgrove. He told the Bishop of Worcester that a letter had been sent to the “Commons persuading them against their Prince under pretence of a pilgrimage … [and that] … William Horrwoode, the priest of St John’s Church, had received one”.

The leaders were captured. Aske was executed in York, others beheaded in London. In all some 200 people were killed for their part in the movement.

Left, Henry VIII

Illustrations and text about Chartism.

The text reads:

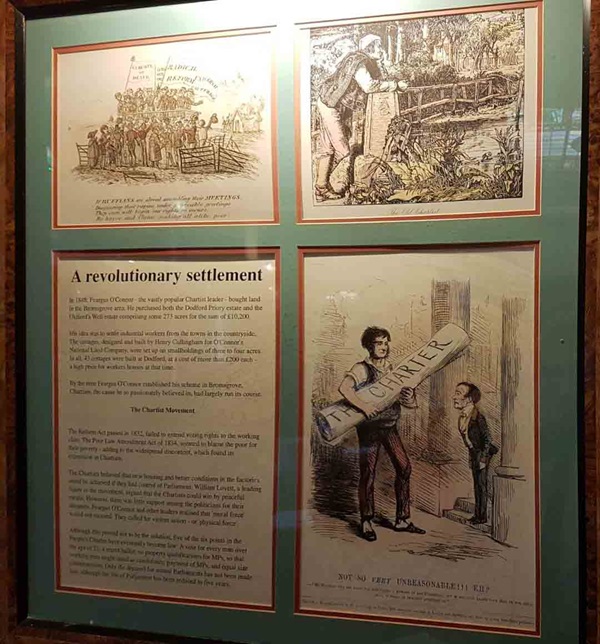

In 1848, Feargus O’Connor – the vastly popular Chartist leader – bought land in the Bromsgrove area. He purchased both the Dodford Priory estate and the Oldford’s Well estate compromising some 273 acres for the sum of £10,200.

His idea was to settle industrial workers from the towns in the countryside. The cottages, designed and built by Henry Cullingham for O’Connor’s National Land Company, were set up on smallholdings of three to four acres. In all, 43 cottages were built at Dodford, at a cost of more than £200 each – a high price for workers houses at that time.

The Reform Act passed in 1832, failed to extend voting rights to the working class. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, seemed to blame the poor for their poverty – adding to the widespread discontent, which found its expression in Chartism.

The Chartists believed that new housing and better conditions in the factories could be achieved if they had control of Parliament. William Lovett, a leading figure in the movement, argued that the Chartists could win by peaceful means. However, there was little support among the politicians for their demands. Feargus O’Connor and other leaders realised that ‘moral force’ would not succeed. They called for violent action – or ‘physical force’.

Although this proved not to be the solution, five of the six points in the People’s Charter have eventually become law: A vote for every man over the age of 21; a secret ballot; no property qualifications for MPs, so that working men might stand as candidates; payments of MPs and equal size constituencies. Only the demand for annual Parliaments has not been made law, although the life of Parliament has been reduced to five years.

A photograph and text about the Golden Cross.

The text reads:

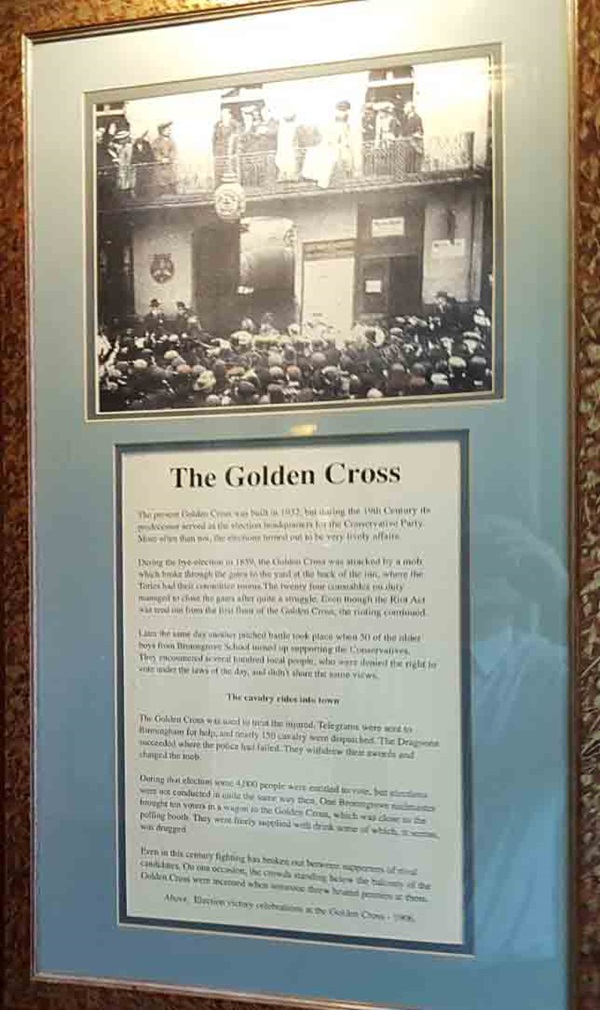

The present Golden Cross was built in 1932, but during the 19th century its predecessor served as the election headquarters for the Conservative Party. More often than not, the elections turned out to be very lively affairs.

During the bye-election in 1859, the Golden Cross was attacked by a mob which broke through the gates to the yard at the back of the inn, where the Tories had their committee rooms. The twenty four constables on duty managed to close the gates after quite a struggle. Even though the Riot Act was read out from the first floor of the Golden Cross, the rioting continued.

Later the same day another pitched battle took place when 50 of the older boys from Bromsgrove School turned up supporting the Conservatives. They encountered several hundred local people, who were denied the right to vote under the laws of the day, and didn’t share the same views.

The Golden Cross was used to treat the injured. Telegrams were sent to Birmingham for help, and nearly 150 cavalry were dispatched. The Dragoons succeeded where the police had failed. They withdrew their swords and charged the mob.

During the election some 4,000 people were entitled to vote, but elections were not conducted in quite the same way then. One Bromsgrove nail master brought ten voters in a wagon to the Golden Cross, which was close to the polling booth. They were freely supplied with drink some of which, it seems, was drugged.

Even in this century fighting has broken out between supporters of rival candidates. On one occasion, the crowds standing below the balcony of the Golden Cross were incensed when someone threw heated pennies at them.

Above: Election victory celebrations at the Golden Cross – 1906.

An illustration and text about Doctor Richard Gem.

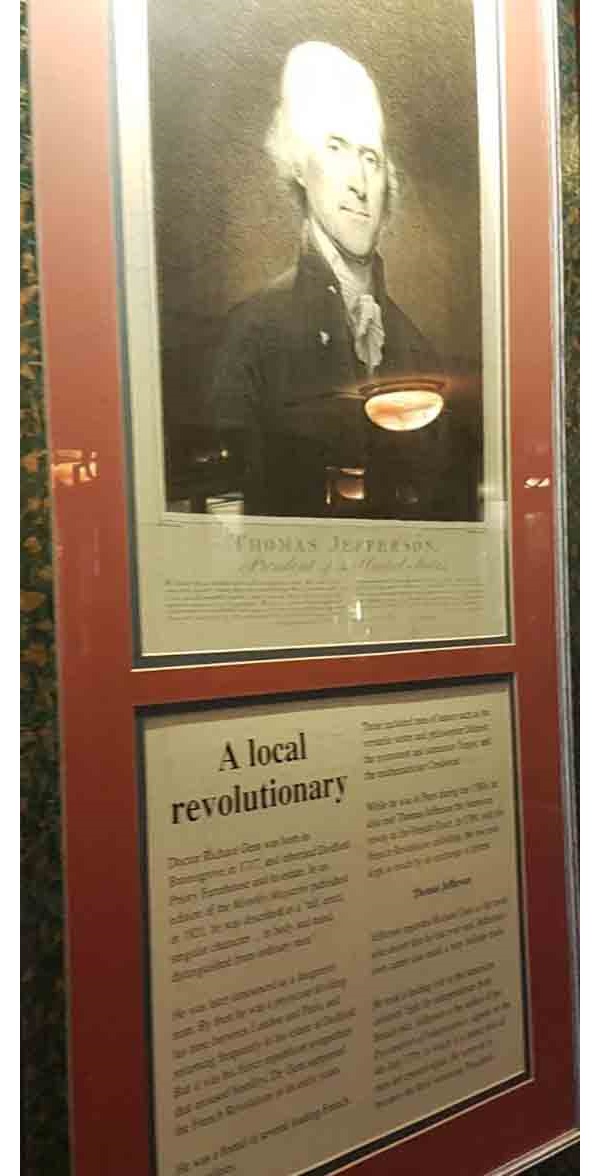

The text reads: Doctor Richard Gem was born in Bromsgrove in 1717, and inherited Dodford Priory Farmhouse and its estate. In an edition of the Monthly Magazine published in 1821, he was described as a “tall, erect, singular character … in body and mind, distinguished from ordinary men”.

He was later denounced as a dangerous man. By then he was a physician dividing his time between London and Paris, and returning frequently to his estate at Dodford. But it was his fierce republican sympathies that aroused hostility. Dr Gem supported the French Revolution in its early years. He was a friend of several leading French personalities.

While he was in Paris during the 1780s, he also met Thomas Jefferson the American envoy to the French court. In 1789, with the French Revolution unfolding, the men kept in touch by an exchange of letters.

Jefferson regarded Richard Gem as the most noble doctor that he had ever met. Jefferson’s own career also made a very definite mark.

He took a leading role in the American colonies fight for independence from British rule. Jefferson is the author of the Declaration of Independence, signed on the 4 July 1776, in which it is stated that all men are created equal. He went on to become the third American president.

Illustrations and text about the hardships of earning of living.

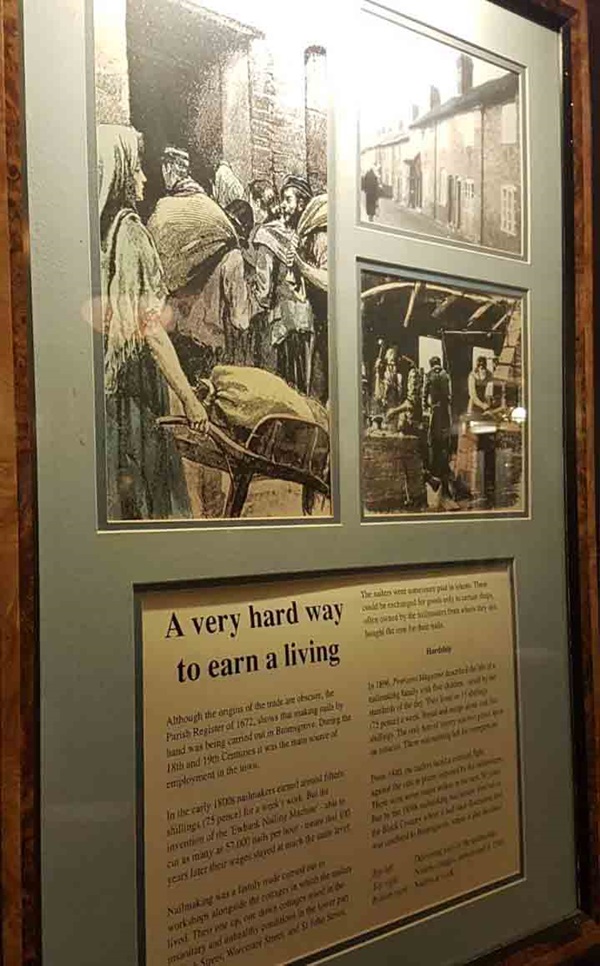

The text reads: Although the origins of the trade are obscure, the Parish Register of 1672, shows that making nails by hand was being carried out in Bromsgrove. During the 18th and 19th centuries it was the main source of employment in the town.

In the early 1800s nail-makers earned around fifteen shillings (75 pence) for a week’s work. But the invention of the ‘Ewbank Nailing Machine’ – able to cut as many as 57,000 nails per hour – meant that 100 years later their wages stayed at much the same level.

Nail-making was a family trade carried out in workshops alongside the cottages in which the nailers lived. Their one up, one down cottages stood in the insanitary and unhealthy conditions in the lower part of High Street, Worcester Street, and St John Street.

The nailers were sometimes paid in tokens. These could be exchanged for goods only in certain shops, often owned by the nail-masters from whom they also bought the iron for their mails.

In 1896, Pearsons Magazine described the life of a nail-making family with five children – small by the standards of the day. They lived on 15 shillings (75 pence) a week. Bread and marge alone cost five shillings. The only hint of luxury was two pence spent on tobacco. There was nothing left for emergencies.

From 1840, the nailers faced a constant fight against the cuts in prices imposed by the nail-masters. There were seven major strikes in the next 50 years. But by the 1890s nail-making had almost died out in the Black Country where it had once flourished, and was confined to Bromsgrove, where is also declined.

Top left: Delivering nails to the nail-master

Top right: Nailers cottages, demolished in 1840

Bottom right: Nailers at work.

Illustrations and text about buildings in Bromsgrove.

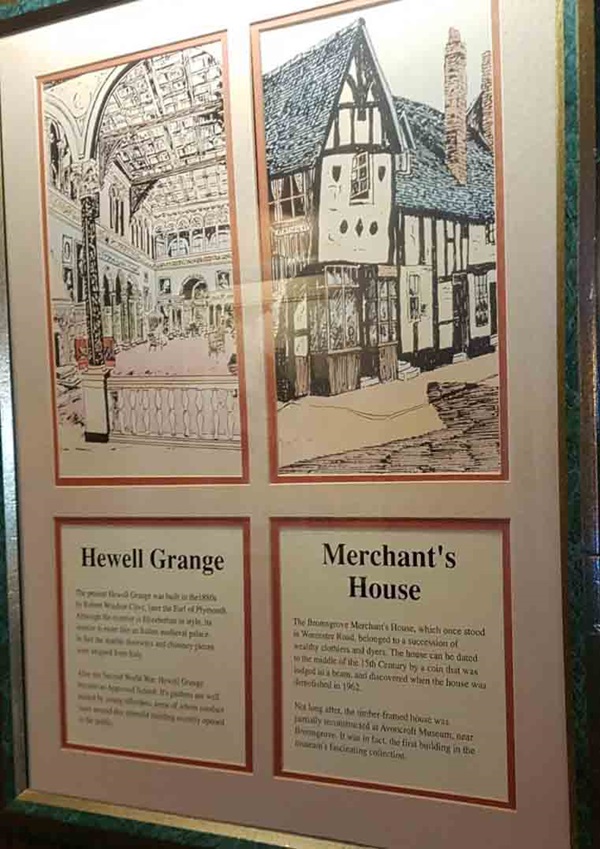

The text reads: Hewell Grange

The present Hewell Grange was built in the 1880s by Robert Windsor-Clive, later the Earl of Plymouth. Although the exterior is Elizabethan in style, its interior is more like an Italian medieval palace. In fact the marble doorways and chimney pieces were shipped from Italy.

After the Second World War, Hewell Grange became an approved school. Its gardens are well tended by young offenders, some of whom conduct tours around this splendid building recently opened to the public.

Merchant’s House

The Bromsgrove Merchant’s House, which once stood in Worcester Road, belonged to a succession of wealthy clothiers and dyers. The house can be dated to the middle of the 15th century by a coin that was lodged in a beam, and discovered when the house was demolished in 1962.

Not long after, the timber framed house was partially reconstructed at Avondroft Museum, near Bromsgrove. It was in fact, the first building in the museum’s fascinating collection.

Illustrations and text about the Gunpowder Plot.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk