This pub takes its name from the popular circus which stood close by, on Sauchiehall Street, in the early 20th century. Sauchiehall Street has also been a mecca for entertainment since the 19th century. In 1888, number 326 opened its doors as The Panorama, later becoming an ice-skating rink. Around 1902–1904, Hengler’s Circus took up residence, remaining until 1926, establishing itself as one of the city’s best-loved entertainment venues.

Framed drawings, prints and text about Hengler’s Circus.

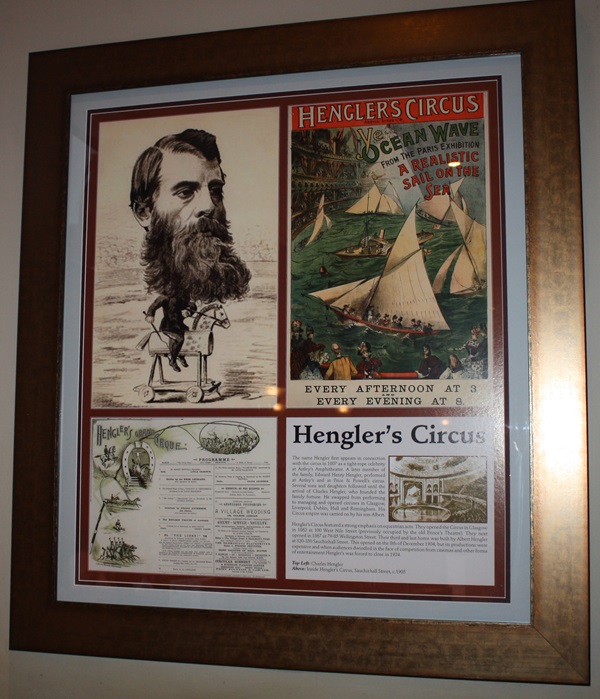

The text reads: The name Hengler first appears in connection with the circus in 1807 as a tight-rope celebrity at Astley’s Ampitheatre. A later member of the family, Edward Henry Hengler, performed at Astley’s and at Price & Powell’s circus. Several sons and daughters followed until the arrival of Charles Hengler, who founded the family fortune. He swapped from performing to managing and opened circuses in Glasgow, Liverpool, Dublin, Hull and Birmingham. His Circus empire was carried on by his son Albert.

Hengler’s Circus featured a strong emphasis on equestrian acta. They opened the Circus in Glasgow in 1862 at 100 West Nile Street (previously occupied by the old Prince’s Theatre). They next opened in 1867 at 79-85 Wellington Street. The third and last home was built by Albert Hengler at 320-330 Sauchiehall Street. This opened on the 8th of December 1904, but its productions were expensive and when audiences dwindled in the face of competition from cinemas and other forms of entertainment Hengler’s was forced to close in 1924.

Top Left: Charles Henglar

Above: Inside Hengler’s Circus, Sauchiehall Street, c.1905.

Framed poster and photo of performances at Hengler’s Circus.

Above: A poster for Hengler’s ‘Grand Cirque’

Below: A horse from Hengler’s Circus salutes Queen Victoria

A famed illustration captioned Grace and skill on horseback.

A framed illustration captioned Bareback Riders, 1886.

A framed photograph of Miss Jenny Louise Hengler, a class equestrian act.

A framed illustration captioned A circus equestrienne, c1850.

A framed illustration captioned A trick rider astounds the circus crowd.

Framed photographs, illustrations and text recounting the history of Madeleine Smith.

The text reads: Madeleine Smith was the first child of an upper-middle-class family in Glasgow. Her father was a wealthy architect, and her mother, the daughter of leading neo classical architect David Hamilton.

In early 1855 Madeleine began a secret love affair with Pierre Emile L’Angelier. Smith’s parents, unaware of the affair, found her a fiancé. Madeleine tried to get L’Angelier to return her love letters. He refused, and threatened to use them to expose her.

Madeleine was seen ordering arsenic from a druggist, and signed in as M.H. Smith. Early in the morning of 23 March 1857, L’Angelier died from arsenic poisoning.

After Smith’s numerous letters were found in his lodging house, she was arrested and charged with murder.

Despite the circumstantial evidence, the jury returned a verdict "not proven". Shortly afterwards, Madeleine left Scotland. She married and lived in London. After many

years, she and her husband separated, and Madeleine moved to New York City and died in 1928 under the name of Lena Wardle Sheehy.

Photos and illustrations include: (Clockwise from bottom left) Madeleine in the dock. She had “the air of a belle entering a ballroom or a box at the opera”; Madeleine (the tallest child) and her family, 1852; Madeleine’s home in Blytheswood Square; Outside court during the trial.

A framed collection of photographs, paintings and text about The Glasgow Boys.

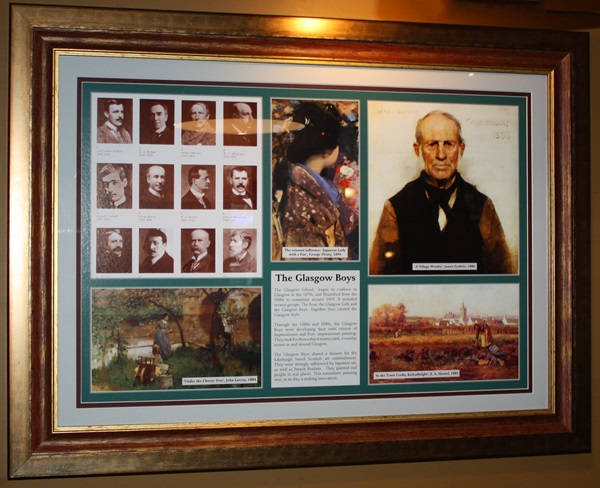

The text reads: The Glasgow School began to coalesce in Glasgow in the 1870s, and flourished from the 1890s to sometime around 1910. It included several groups: The Four, the Glasgow Girls and the Glasgow Boys. Together they created the Glasgow Style.

Through the 1880s and I890s, the Glasgow Boys were developing their own version of impressionist and Post- impressionist painting. They took for their subject matter rural, everyday scenes in and around Glasgow.

The Glasgow Boys shared a distaste for the Edinburgh based Scottish art establishment. They were strongly influenced by Japanese art, as well as French Realism. They painted real people in real places. This naturalistic painting was, in its day, a striking innovation.

The paintings include: (Bottom left) ‘Under the Cherry Tree’, John Lavery, 1884; (middle) The oriental influence: ‘Japanese Lady with a Fan’, George Henry, 1894; (top right) ‘A village Worthy’, James Guthrie, 1886; (bottom right) ‘In the Town Crofts, Kirkudbright’, E.A. Hornel, 1885.

A framed collection of photographs and text about Glasgow’s Citizen’s Theatre.

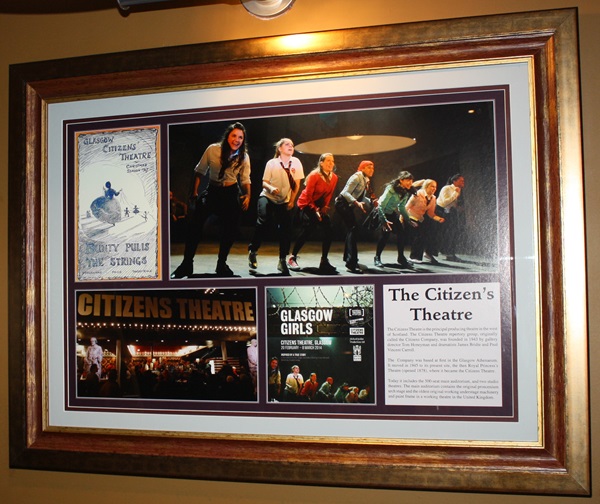

The text reads: The Citizens Theatre is the principal producing theatre in the west of Scotland. The Citizens Theatre repertory group, originally called the Citizens Company, was founded in 1943 by gallery director Tom Honeyman and dramatists James Bridie and Paul Vincent Carroll.

The Company was based at first in the Glasgow Athenaeum. It moved in 1945 to its present site, the then Royal Princess’s Theatre (opened 1878), where it became the Citizens theatre.

Today it includes the 500-seat main auditorium, and two studio theatres. The main auditorium contains the original proscenium arch stage and the oldest original working understage machinery and paint frame in a working theatre in the United Kingdom.

Framed photographs of The King’s Theatre, including a photo of Katherine Hepburn, after her ‘brilliant’ performance in George Bernard Shaw’s The Millionairess, posing on the stairs of the King’s Theatre.

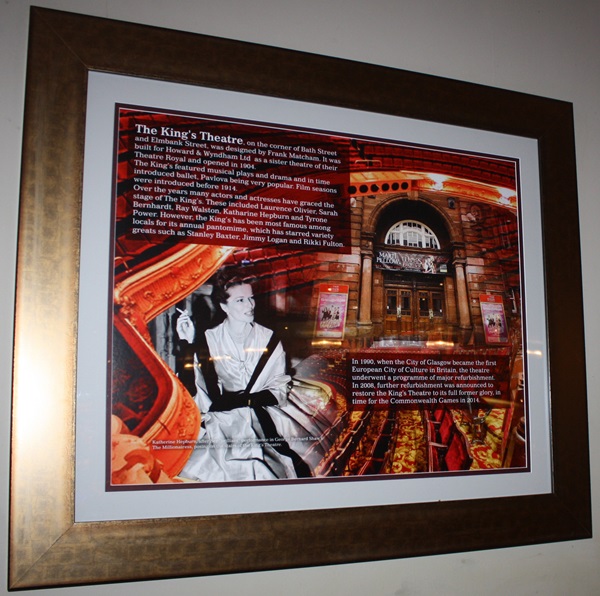

The text reads; (Top Left) The King’s theatre, on the corner of Bath Street and Elmbank Street, was designed by Frank Matcham. It was built for Howard & Wyndham Ltd as a sister theatre of their Theatre Royal and opened in 1904.

The King’s featured musical plays and drama and in time introduced ballet, pavlova being very popular. Film seasons were introduced before 1914.

Over the years many actors and actresses have graced the stage of The King’s. These included Laurence Olivier, Sarah Bernhardt, Ray Walston, Katherine Hepburn and Tyrone power. However, the King’s has been most famous among locals for its annual pantomime, which has starred variety greats such as Stanley Baxter, Jimmy Logan and Rikki Fulton.

(Bottom right) In 1990, when the City of Glasgow became the first European City of Culture in Britain, the theatre underwent a programme of major refurbishment. In 2008, further refurbishment was announced to restore the King’s Theatre to its full former glory, in time for the Commonwealth Games in 2014.

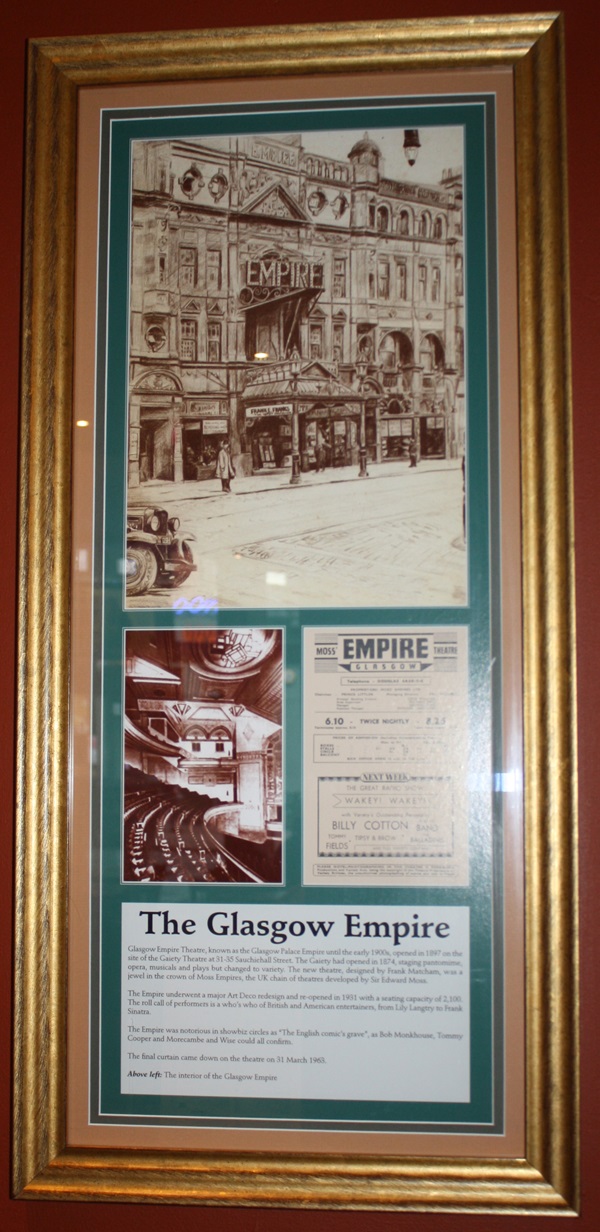

A framed collection of illustrations, a poster and text about the Empire Theatre, Glasgow.

The text reads: Glasgow Empire Theatre, known as the Glasgow palace Empire until the early 1900s, opened in 1897 on the site of the Gaiety Theatre at 31-35 Sauchiehall Street. The Gaiety had opened in 1874, staging pantomime, opera, musicals and plays but changed to variety. The new theatre, designed by Frank Matcham, was a jewel in the crown of Moss Empires, the UK chain of theatres developed by Sir Edward moss.

The Empire underwent a major Art Deco redesign and re-opened in 1931 with a seating capacity of 2,100. The roll call of performers is a who’s who of British and American entertainers, from Lilly Langtry to Frank Sinatra.

The Empire was notorious in showbiz circles as “The English comic’s grave”, as Bob Monkhouse, Tommy Cooper and Morcambe and Wise could all confirm.

The final curtain came down on the theatre on 31 March 1963.

Above left: the interior of the Glasgow Empire

A framed collection of photographs entitled Sauchiehall Street.

A framed collection of photographs, including (left) Marble Bust of Alexander Thomson; (top right) The Cairney Building on the north side of Bath Street, c1905; (bottom right) The Egyptian Halls in Union Street, 1874.

A framed collection of photographs, illustrations and text about Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson.

The text reads: Alexander Thomson was born in Sterlingshire. He was seven when his father died, and the family moved to the outskirts of Glasgow.

In 1857, as ‘the rising architectural star’ of Glasgow, he entered into practice with his brother George.

Thomson’s style, at first a free re-working of Greek and Egyptian sources, settled later into the purely Ionic Greek style for which he is best known. He produced a diverse range of structures including villas, a castle, terraces, warehouses, tenements, and three extraordinary churches.

Those still standing include Grecian Buildings in Sauchiehall Street, Moray Place, Great Western Terrace, Egyptian Halls in Union Street and St Vincent Street Church.

Thomson died in 1875 at the home he designed in Moray Place.

The photos are captioned: (Top left) Alexander Thomson in the 1850’s; (right) the Caledonia Road Church, 1857.

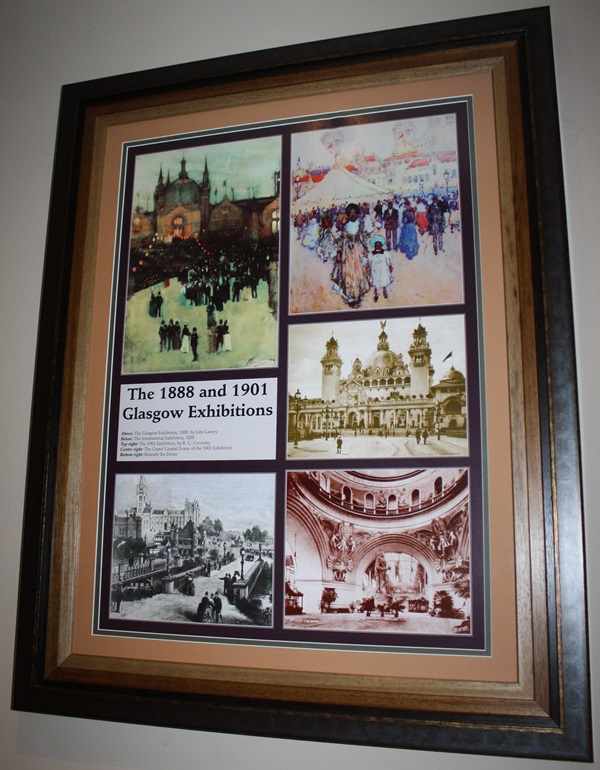

A framed collection of photographs and illustrations entitled The 1888 and 1901 Glasgow Exhibitions.

The photographs and illustrations include (top left) The Glasgow Exhibition, 1888, by John Lavery; (bottom left) The International Exhibition, 1888; (top right) The 1901 Exhibition, by RG Coventry; (centre right) The Grand Central Dome of the 1901 Exhibition; (bottom right) Beneath the Dome.

A framed collection of photographs, illustrations, posters and text about The Empire Exhibition, 1938.

The text reads: The first international exhibition held in Britain was the 1851 event at Crystal palace in London. Its success resulted in a craze for further large – and increasingly grander – exhibitions.

The first great universal exhibition in Glasgow was held in 1888. This was a roaring success and its profits went towards funding a new and permanent Art Gallery and Museum, in Kelvingrove Park. The second exhibition of 1901 was conceived to inaugurate the new building.

The Empire Exhibition, Scotland 1938, held at Bellahouston Park, marked fifty years since Glasgow’s first great exhibition. It also offered a chance to boost the economy of Scotland, recovering from the depression of the 1930s. Despite 1938 being one of the wettest summers on record, the Exhibition attracted 12 million visitors.

The most prominent structure was the Tait Tower (officially the Tower of Empire), 470 feet high (143.25 m). Although it was intended to remain as a permanent monument after the exhibition, the tower was demolished in July 1939.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk