This ornate building was designed as the town’s general post office by WW Robertson and the Office of Works. Built at a cost of £20,000, it first opened its doors in 1899. The premises are now named after James Watt, the inventor and mechanical engineer born in Greenock in 1736. His improvements to the steam engine powered the Industrial Revolution which changed the world. Watt also introduced the word horsepower – to indicate an engine’s power.

Prints and text about The James Watt.

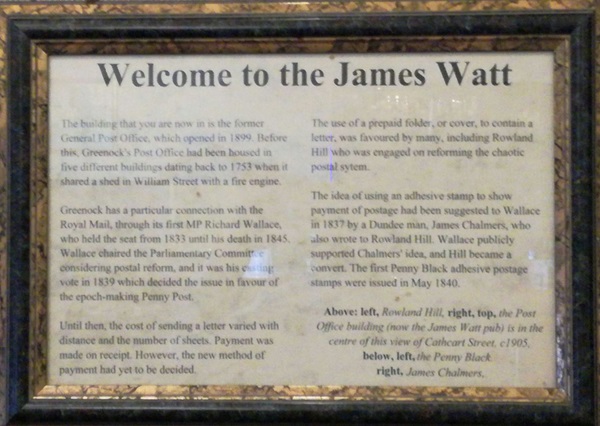

The text reads: The building that you are now in is the former general post office, which opened in 1899. Before this, Greenock’s post office had been housed in five buildings dating back to 1753 when it shared a shed in William Street with a fire engine.

Greenock has a particular connection with the Royal Mail, through its first MP Richard Wallace, who held the seat from 1833 until his death in 1845. Wallace chaired the Parliamentary committee considering postal reform, and it was his evening vote in 1839 which decided the issue in favour of the epoch-making Penny Post.

Until then, the cost of sending a letter varied with distance and the number of sheets. Payment was made on receipt. However, the new method of payment had yet to be decided.

The use of a prepaid folder, or cover, to contain a letter, was favoured by many, including Rowland Hill who was engaged on reforming the chaotic postal system.

The idea of using an adhesive stamp to show payment of postage had been suggested to Wallace in 1837 by a Dundee man, James Chalmers, who also wrote to Rowland Hill. Wallace publicly supported Chalmers’ idea, and Hill became a convert. The first Penny Black adhesive postage stamps were issued in May 1840.

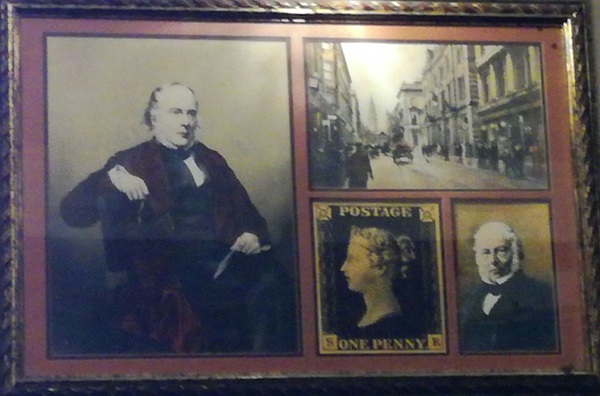

Above: left, Rowland Hill, right top, the post office building (now the James Watt pub) is in the centre of this view of Cathcart Street c1905, below left, the Penny Black, right, James Chalmers.

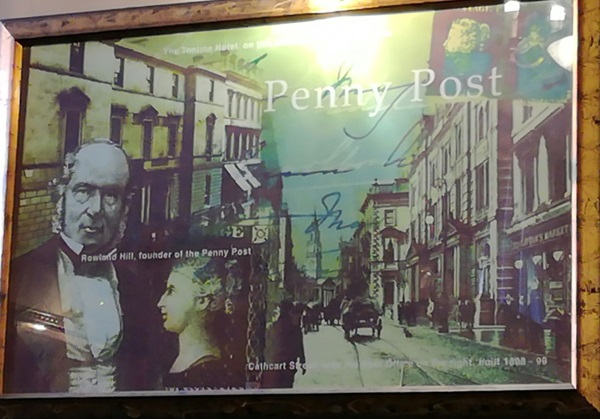

Prints relating to the Penny Post.

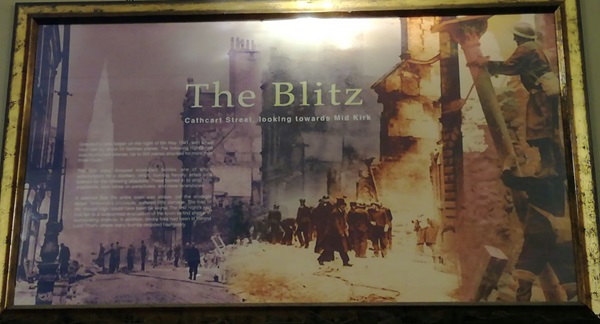

Prints and text about the Blitz.

The text reads: Greenock’s blitz began on the night of 6 May 1941, with a two hour raid by about 50 German planes. The following night’s raid was much more intense. Up to 300 planes attacked for more than 3 hours.

The first wave dropped incendiary bombs, one of which unfortunately hit a distillery, which burning fiercely, acted as a beacon for the following attackers. These homed in to drop high explosives, land mines on parachutes, and more incendiaries.

It seemed that the entire town was ablaze, yet the strategic target, Greenock’s shipyards, suffered little damage. The first night’s raid had led to widespread evacuation of the town to find shelter in surrounding districts. In addition, decoy fires had been lit behind Loch Thom, where many bombs dropped harmlessly.

A print and text about Lord Nelson.

The text reads: After his fatal injury on board HMS Victory, Britain’s great naval hero was carried to the cockpit “in the arms of a Greenock man”. The town subsequently recognised Lord Nelson and his local connection by naming three streets, one after the man himself, and Nile Street and Trafalgar Street after two of his victories.

Horatio Nelson went to sea at the age of twelve, serving as midshipman under his uncle, Captain Suckling. By fifteen, he had voyaged to the West Indies, and to the Arctic.

In 1779, Nelson obtained his first captaincy, in a campaign against the Spanish in central America. A later voyage to the West Indies was a failure, and he waited six years for his next command.

He was recalled during the wars against France, and sent to Naples. It was here that he first met Emma Hamilton, wife of the British ambassador.

Victories in the Mediterranean and at Cape St Vincent established Nelson’s national reputation. He was knighted, and promoted Rear-Admiral.

Nelson is best known for his last battles. In 1798, he destroyed the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile, and four years later defeated Napoleon’s Danish allies at Copenhagen. His final victory at Trafalgar established British naval supremacy for a century.

Above: The Battle of Trafalgar, 1805 – the death of Nelson.

An illustration and text about the PS Britannia crossing the Atlantic.

The text reads: The paddle-steamer Britannia – built in Greenock in 1840 – was the first ever vessel commissioned for Cunard’s transatlantic service.

The founder of the famous shipping line – Samuel Cunard – had gone against tradition in calling for ships which were “plain and comfortable”. In1842 Charles Dickens was able to judge for himself when he crossed the Atlantic for a lecture tour in America.

He described his cabin as “an utterly impractical… hopeless and profoundly preposterous box”.

He added that the dining room was “a hearse with windows” and the food was a “smoking mess of hot collops followed by a rather mouldy dessert of apples, grapes and oranges”. To make matters worse, the weather was appalling. Not surprisingly the famous writer did not return home on the Britannia.

The ship made some 40 round trips to America. She spent her last years in the Prussian Navy, before being sunk in 1880.

Right: Shipyard on the Clyde.

Prints and text about steam ships and paddle steamers.

The text reads: James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine made steam-powered land and water transport a real possibility. However, he left it to others to develop the idea.

William Symington, a mining engineer, took out a patent in 1786, and constructed the first steamship, Charlotte Dundas, on Dalswinton Lock. Robert Burns was an early passenger. In 1802 a tug of the same name performed successfully on the Forth and Clyde Canal, but the canal owners claimed its wash damaged the banks.

Two men took Symington’s ideas forward. An American, Robert Fulton, went on to build steamships on the rivers Seine and the Hudson. Henry Bell designed a 45-foot wooden paddle-steamer, Comet, which was launched in July 1812.

For several years Bell’s Comet ran between Glasgow, Greenock and Helensburgh, the first passenger-carrying steamboat in European waters.

He later opened a route via the Crinan and Caledonian canals to Inverness. However, the Comet was wrecked off Oban in 1820. The engine was salvaged and used in a brewery for 40 years before being bought and presented to The Science Museum, in London. In 1962, Lithgown Yard launched an exact replica of the Comet.

Bell offered the idea of steam navigation to the British Government in 1813, but he was informed that it had “no utility”.

Above: left, Henry Bull

Right: top, the Charlotte Dundas, below, the Comet.

Prints, an illustration and text about The Tontine Hotel.

The text reads: For most of the 19th century, this site was the original position of the Tontine Hotel.

The unusual name is derived from the Italian banker Lorenzo Tonti, who devised a method of financing projects whereby a fixed income is divided between shareholders. As each shareholder dies, their share is distributed amongst the rest. This method was used to raise the £10,000 needed to pay for the hotel.

The hotel, with its 30 bedrooms and twelve sitting rooms, was designed by the Edinburgh architect John Paterson. It opened for business in 1803, and operated until 1892, when the site was bought by the government for the building of a new post office.

The proprietress, a Mrs Buchanan, then took the tenancy of a former private house of Ardgowan Square, which she converted into a hotel, using the same name as her previous establishment.

The second Tontine Hotel, described as the finest mansion in Greenock, was originally the residence of one of the town’s foremost inhabitants, George Robertson. He was a senior magistrate, with a fortune based on his partnership on a Newfoundland trading company. Built in 1808 on the site of an old windmill, the house was for some time the most westerly building in Greenock.

Above: top, the Tontine Hotel on this site

Below: left, the Tontine Hotel, Ardgowan Square, right, the Tontine Hotel, Cathcart Street, 1801.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

Extract from Wetherspoon News Spring 2019.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk