Originally a 19th-century chapel, this was rebuilt as the Comrades Club in 1949. In 1992, the building became The Sussex public house, named after the street it is in. The street is named after the Duke of Sussex, one of the many titled visitors to Rhyl in its heyday – when it was as a resort for the well-to-do.

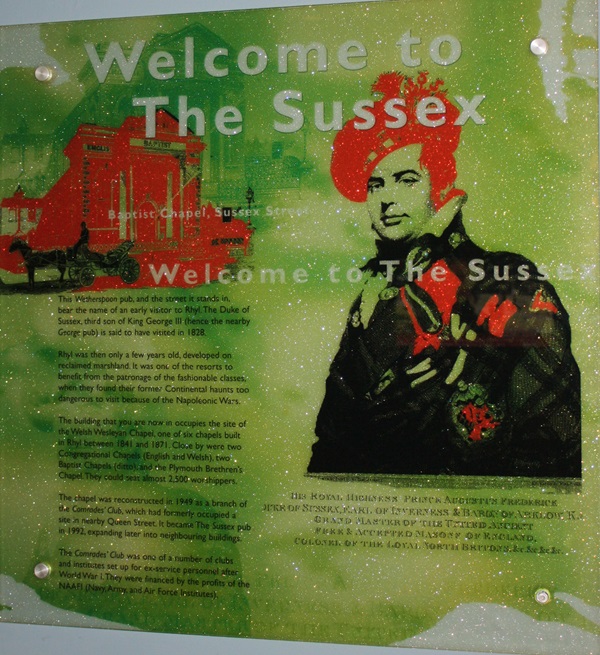

Prints, photographs and text about The Sussex.

The text reads: The Duke of Sussex was the third son of King George III. He was early visitor to the resort of Rhyl, coming in 1828. His patronage was commemorated by naming this street after him, and by the name of this Wetherspoon freehouse.

This stands on the site of Zion Welsh Wesleyan Chapel, erected in 1833, which was replaced by St Georges Hall, and then in 1949 by the Old Comrades Memorial Club. It became the Sussex pub in 1992.

Prints and text about The Sussex.

The text reads: This Wetherspoon pub, and the street it stands in, bears the name of an early visitor to Rhyl. The Duke of Sussex, third son of King George III (hence the nearby George pub) is said to have visited in 1828.

Rhyl was then only a few years old, developed on reclaimed marshland. It was one of the resorts to benefit from the patronage of the fashionable classes, when they found their former Continental haunts too dangerous to visit because of the Napoleonic Wars.

The building that you are now in occupies the site of the Welsh Wesleyan Chapel, one of six chapels built in Rhyl between 1841 and 1871. Close by were two Congregational Chapels (ditto), and the Plymouth Brethren’s Chapel. They could seat almost 2,500 worshippers.

The chapel was reconstructed in 1949 as a branch of the Comrades’ Club, which had formerly occupied a site in nearby Queen Street. It became The Sussex pub in 1992, expanding later into neighbouring buildings.

The Comrades’ Club was one of a number of clubs and institutes set up for ex-service personnel after World War I. They were financed by the profits of the NAAFI (Navy, Army, and Air Force Institutes).

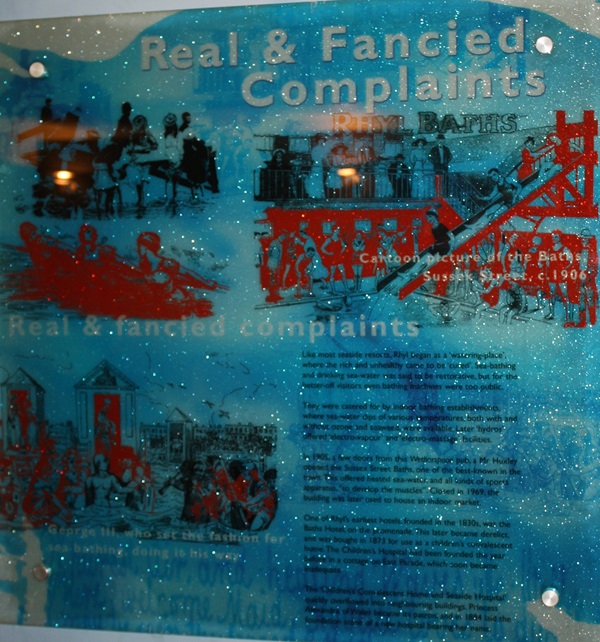

Illustrations and text about what brought the rich to Rhyl.

The text reads: Like most seaside resorts, Rhyl began as a ‘watering- place’, where the rich and unhealthy came to be ‘cured’. Sea-bathing and drinking sea-water was said to be restorative, but for the better-off visitors even bathing machines were too public.

They were catered for by indoor bathing establishments, where sea-water dips of various temperatures both with and without ozone and seaweed, were available. Later ‘hydros’ offered ‘electro-vapour’ and ‘electro-massage’ facilities.

In 1905, a few doors from this Wetherspoon pub, a Mr Huxley opened the Sussex Street Baths, one of the best-known in the town. This offered heated-sea-water, and all kinds of sports apparatus, “to develop the muscles”. Closed in 1969, the building was later used to house an indoor market.

One of Rhyl’s earliest hotels, founded in the 1830s, was the Baths Hotel, on the promenade. This later became derelict, and was bought in 1873 for use as a children’s convalescent home. The Children’s Hospital had been founded the year before in a cottage on East Parade, which soon became inadequate.

The ‘Children’s Convalescent Home and Seaside Hospital’ quickly overflowed into neighbouring buildings. Princess Alexandra of Wales became its patron, and in 1884 laid the foundation stone of a new hospital bearing her name.

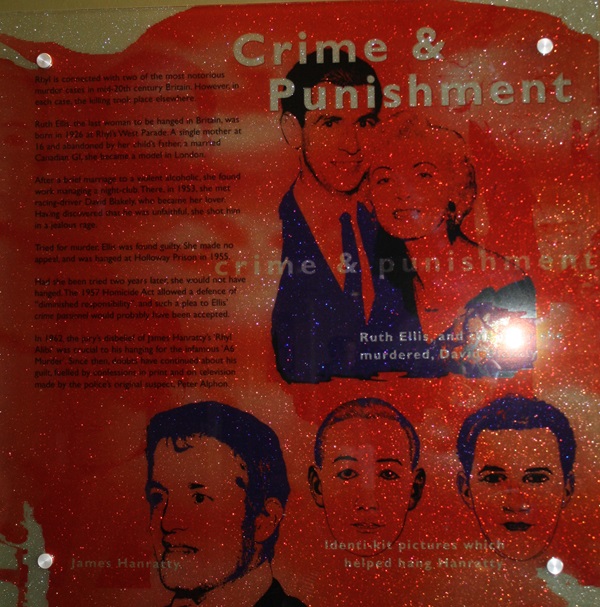

Photographs and illustrations about crime and punishment in Rhyl.

The test reads: Rhyl is connected with two of the most notorious murder cases in mid 20th century Britain. However, in each case, the killing took place elsewhere.

Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain, was born in 1926 at Rhyl’s West Parade. A single mother at 16 and abandoned by her child’s father, a married Canadian Gl, she became a model in London.

After a brief marriage to a violent alcoholic, she found work managing a night- club. There, in 1953, she met racing- driver David Blakely, who became her lover. Having discovered that he was unfaithful, she shot him in a jealous rage.

Tried for murder, Ellis was found guilty. She made no appeal, and was hanged at Holloway Prison in 1955.

Had she been tried two years later, she would not have hanged. The 1957 Homicide Act allowed a defence of “diminished responsibility”, and such a plea to Ellis’ crime passionel would probably have been accepted.

In 1962, the jury’s disbelief of James Hanratty’s ‘Rhyl Alibi’ was crucial to his hanging for the infamous ‘A6 Murder’. Since then, doubts have continued about his guilt, fuelled by confessions in print and on television made by the police’s original suspect, Peter Alphon.

Photographs and text about The Pavilion and The Queen’s Theatre.

The text reads: The Pavilion and The Queen’s Theatre were Rhyl’s two leading places of entertainment.

The first Grand Pavilion was built in 1891 at the shore end of the Pier. This burnt down in the early 1900s and a new Pavilion was built on the Promenade in 1908. Amidst great controversy, this much-loved building was demolished in 1974.

The Queen’s Theatre and Ballroom was part of the Queens Palace complex, which opened in 1902. The original structure burned down in 1907.

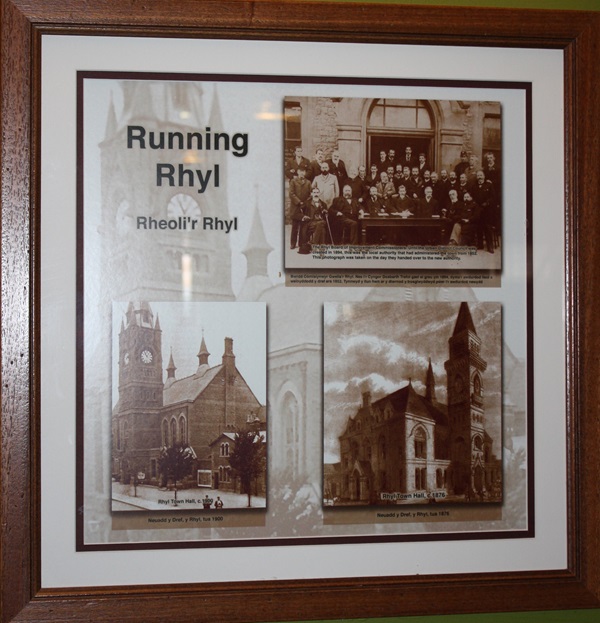

Photographs and text about authority in Rhyl.

The text reads: The Rhyl Board of Improvement Commissioners. Until the Urban District Council was created in 1894, this was local authority that had administered the town from 1852. This photograph was taken on the day they handed over to the new authority.

Illustrations and text about Rhuddlan Castle.

The text reads: Built between 1277 and 1282 for King Edward I, Rhuddian castle was damaged during the Civil Wars, and later pillaged for building stone. There is reason to believe that Rhuddian, rather than Caernarfon, was where Edward I presented his son to the Welsh nobles as Prince in 1284.

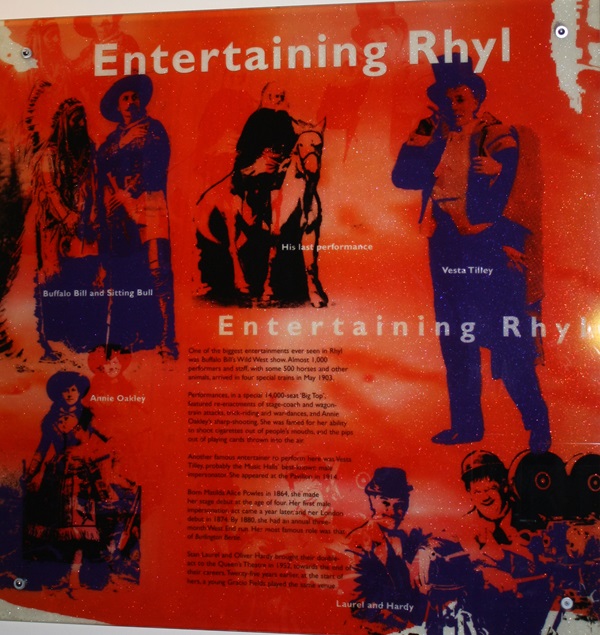

Illustrations and text about entertainment in the area.

The text reads: One of the biggest entertainments ever seen in Rhyl was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Almost 1,000 performers and staff, with some 500 horses and other animals, arrived in four special trains in May 1903.

Performances, in a special 14,000-seat ’Big Top’, featured re-enactments of stage-coach and wagon-train attacks, trick-riding and war-dances, and Annie Oakley’s sharp- shooting. She was famed for her ability to shoot cigarettes out of people’s mouths, and the pips out of playing cards thrown into the air.

Another famous entertainer to perform here was Vesta Tilley, probably the Music Halls’ best-known male impersonator. She appeared at the Pavilion in 1914.

Born Matilda Alice Powles in 1864, she made her stage debut at the age of four. Her first male impersonation act came a year later, and her London debut in 1874. By 1880, she had an annual three-month West End run. Her most famous role was that of Burlington Bertie.

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy brought their double-act to the Queen’s Theatre in 1952, towards the end of their careers. Twenty-five years earlier, at the start of her, a young Gracie Fields played the same venue.

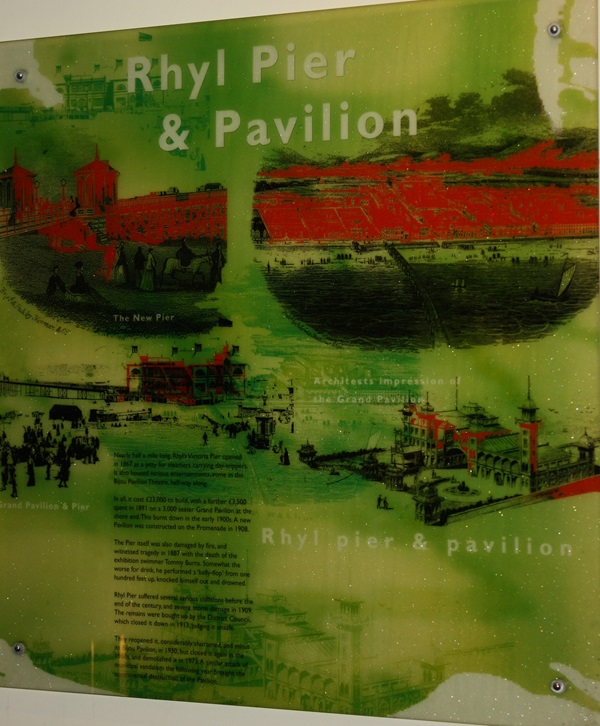

Illustrations and text about Rhyl Pier and Pavilion.

The text reads: Nearly half a mile long, Rhyl’s Victoria Pier opened in 1867 as a jetty for steamers carrying day-trippers. It also housed various entertainments, some in the Bijou Pavilion Theatre, half-way along.

In all, it cost £23,000 to build, with a further £3,500 spent in 1891 on a 3,000 seater Grand Pavilion at the shore end. This burnt down in the early 1900s. A new Pavilion was constructed o the Promenade in 1908.

The Pier itself was also damaged by fire, and witnessed tragedy 1887 with the death of the exhibition swimmer Tommy Burns. Somewhat the worse for the drink, he performed a ‘belly-flop’ from one hundred feet up, knocked himself out and drowned.

Rhyl Pier suffered several serious collisions before the end of the century, and severe storm damage in 1909. The remains were bought up by the District Council, which closed it down in 1913, judging it unsafe.

They reopened it, considerably shortened, and minus its Bijou Pavilion, in 1930, but closed it again in the 1960s, and demolished it in 1973.A similar attack of municipal vandalism the following year brought the controversial destruction of the Pavilion.

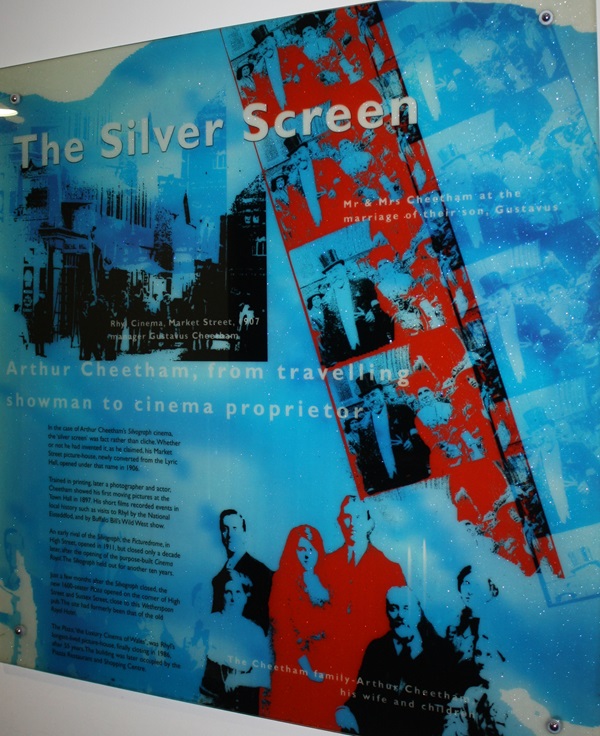

Prints and text about the ‘silver screen’.

The text reads: In the case of Arthur Cheetham’s Silvograph cinema, the ‘silver screen’ was fact rather than cliché. Whether or not he had invented it, as he claimed, his Market Street picture-house, newly converted from the Lyric Hall, opened under the name in 1906.

Trained in printing, later a photographer and actor, Cheetham showed his first moving pictures at the Town Hall in 1897. His short films recorded events in local history such as visits to Rhyl by the National Eisteddfod, and by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

An early rival of the Silvograph, the Picturedrome, in High Street, opened in 1911, but closed only a decade later, after the opening of the purpose-built Cinema Royal. The Silvograph held out for another ten years.

Just a few months after the Silvograph closed, the new 1600-seater Plaza opened on the corner of High Street and Sussex Street, close to this Wetherspoon pub. The site had formerly been that of the old Royal Hotel.

The Plaza, ‘the Luxury Cinema of Wales’, was Rhyl’s longest-lived picture-house, finally closing in 1986, after 55 years. The building was later occupied by the Piazza Restaurant and Shopping Centre.

The front of the pub commemorates the Old Comrades Memorial Club.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk