This was originally a 17th-century coaching inn. It is said to have been visited by Charles I during the Civil War in the 1640s. The plaster overmantel (opposite), dating from the 1670s, is probably intended to be his portrait. At that time, the inn was owned by Richard Ballard, who acted as both mayor and postmaster. In the 1800s, this was one of Monmouth’s most important inns, often used for corporation dinners. One such event was held in 1840 to celebrate the wedding of Queen Victoria.

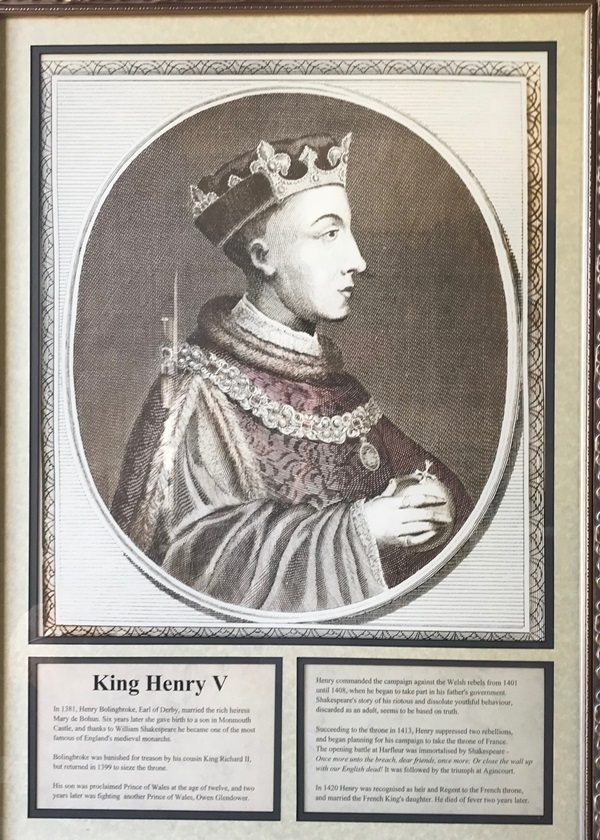

An illustration and text about King Henry V.

The text reads: In 1381, Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby, married the rich heiress Mary de Bohun. Six years later she gave birth to a son in Monmouth Castle, and thanks to William Shakespeare he became one of the most famous of England’s medieval monarchs.

Bolingbroke was banished for treason by his cousin King Richard II, but returned in 1399 to seize the throne.

His son was proclaimed Prince of Wales at the age of twelve, and two years later was fighting another Prince of Wales, Owen Glendower.

Henry commanded the campaign against the Welsh rebels from 1401 until 1408, when he began to take part in his father’s government. Shakespeare’s story of his riotous and dissolute youthful behaviour, discarded as an adult, seems to be based on truth.

Succeeding to the throne in 1413, henry suppressed two rebellions, and began planning for his campaign to take the throne of France. The opening battle at Harfleur was immortalised by Shakespeare – Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more; Or close the wall up with our English dread! It was followed by triumph at Agincourt.

In 1420 Henry was recognised as heir and Regent to the French throne, and married the French King’s daughter. He died of fever two years later.

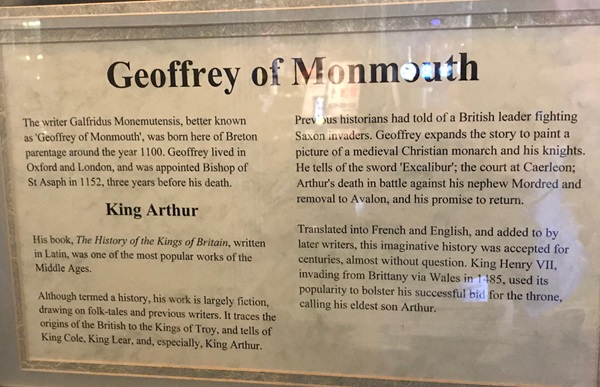

Text about Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The text reads: The writer Galfridus Monemutensis, better known as ‘Geoffrey of Monmouth’, was born here of Breton parentage around the year 1100. Geoffrye lived in Oxford and London, and was appointed Bishop of St Asaph in 1152, three years before his death.

His book, The History of the Kings of Britain, written in Latin, was one of the most popular works of the Middle Ages.

Although termed a history, his work is largely fiction, drawing on folk tales and previous writers. It traces the origins of the British to the Kings of Troy, and tells of King Cole, King Lear, and, especially King Arthur.

Previous historians had told of a British leader fighting Saxon invaders. Geoffrye expands the story to paint a picture of a medieval Christian monarch and his knights. He tells of the sword Excalibur, the court at Caerleon; Arthur’s death in battle against his nephew Mordred and removal to Avalon, and his promise to return.

Translated into French and English, and added to by later writers, this imaginative history was accepted for centuries, almost without question. King Henry VII, invading from Brittany via Wales in 1485, used its popularity to bolster his successful bid for the throne, calling his eldest son Arthur.

Illustrations and text about William Cobbett.

The text reads: In 1820, the campaigning writer William Cobbett visited Monmouth, where he gave a lecture in The King’s Head. According to hostile local newspaper reports, only 30 people attended, perhaps due to the two shillings (10p) entrance fee.

Cobbett, born in 1763, had an eventful life. He ran away to London at the age of eleven, working as a gardener and a clerk, before joining the army and being posted to America. Although only a sergeant, he was virtually in charge of a garrison there, because he was able to read, write and think more clearly than the officers.

Cobbett became a journalist and his attacks on corruption in high places were so resented that he had to escape abroad several times. He later spent two years in prison for publishing seditious libel in his newspaper The Political Register.

Although Cobbett wrote over 50 books, he is best known for his Rural Rides, a collection of pieces recording his observations on living and working conditions in the English countryside. He also initiated reports of Parliamentary proceedings, later known by the name of his printer and publisher, Hansard. He became an MP himself in 1832, representing Oldham, but died just three years later.

Top: Portrait of William Cobbett

Above: Cobbett on the stump.

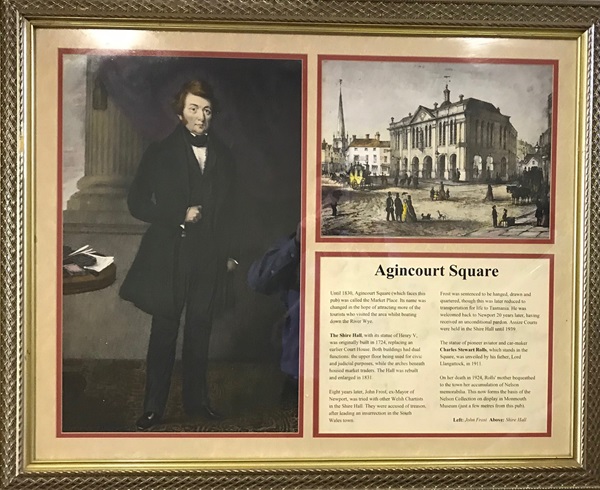

Illustrations and text about Agincourt Square.

The text reads: Until 1830, Agincourt Square (which faces this pub) was called the Market Place. Its name was changed in the hope of attracting more of the tourists who visited the area whilst boating down the River Wye.

The Shire Hall, with its statue of Henry V, was originally built in 1724, replacing an earlier Court House. Both buildings had dual functions, the upper floor being used for civic and judicial purposes, while the arches beneath housed market traders. The hall was rebuilt and enlarged in 1831.

Eight years later, John Frost, ex-mayor of Newport, was tried with other Welsh Chartists in the Shire Hall. They were accused of treason, after leading an insurrection in the south Wales town.

Frost was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, though this was later reduced to transportation to Tasmania. He was welcomed back to Newport 20 years later, having received an unconditional pardon. Assize Courts were held in the Shire Hall until 1939.

The statue of pioneer aviator and car-maker Charles Stewart Rolls, which stands in the Square, was unveiled by his father, Lord Llangattock, in 1911.

On her death in 1924, Rolls’ mother bequeathed to the town her accumulation of Nelson memorabilia. This now forms the basis of the Nelson Collection on display in Monmouth Museum (just a few metres from this pub).

Left: John Frost

Above: Shire Hall

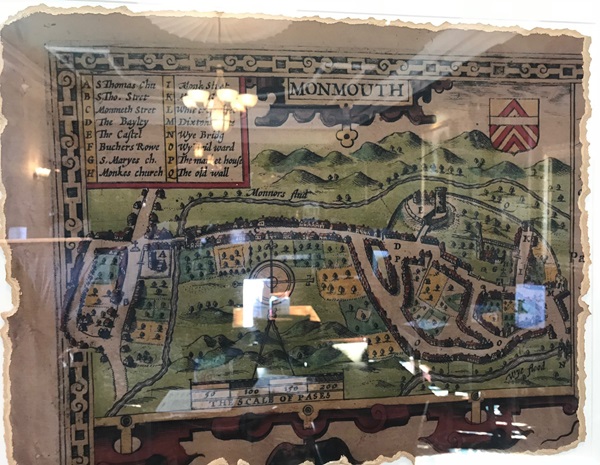

A print, illustration and text about the history of Monmouth.

The text reads: A market first developed in Monmouth following the construction of the castle. The market was originally held along Monmow Street, but traders also used an area inside the castle wall.

The charter granted to the town by Henry VI in 1447, gave the inhabitants a monopoly of markets and fairs for a five mile radius. It also gave the mayor and bailiffs the power to regulate them. The town’s status was improved a century later when Monmouth became a county town.

Its prosperity depended on its market. Monmow Street was wide and gated – at one end by St Stephen’s Gate and at the other by the fortification of Monmow Bridge.

This prevented the escape of sheep and cattle, which were traded there until 1876. Other produce was also sold in Monmow Street.

In 1571 traders complained when they were forced to pay for the privilege of using the new Market Hall. This building was replaced in 1724 to provide accommodation for courts and the corporation, as well as traders.

This in turn was restored and enlarged in 1850, not long after the Market Place had been renamed Agincourt Square, in a bid to encourage tourism.

Right: King Henry VI, who granted the town’s charter in 1447

Above: Monmow Bridge.

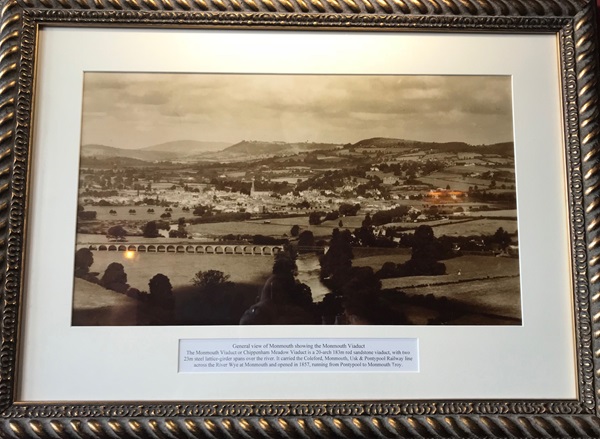

A photograph of Monmouth showing the Monmouth Viaduct.

The Monmouth Viaduct or Chippenham Meadow Viaduct is a 20 arch 183m red sandstone viaduct, with two 23m steel lattice-girder spans over the river. It carried the Coleford, Monmouth, Usk & Pontypool Railway line across the River Wye at Monmouth and opened in 1857, running from Pontypool to Monmouth Troy.

An illustration of Charles I during the Civil War.

An old illustration of Monmouth.

A medieval tapestry.

A painting entitled Lady Writing a Letter, by Jan Vermeer.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

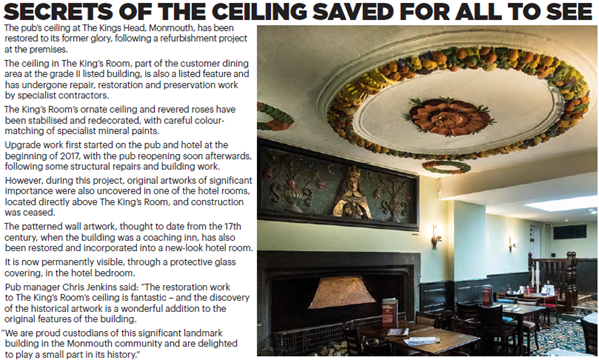

Extract from Wetherspoon News Autumn 2019.

If you have information on the history of this pub, then we’d like you to share it with us. Please e-mail all information to: pubhistories@jdwetherspoon.co.uk